In many export transactions, the buyer is unable or unwilling to pay for the goods at the time of delivery. This means that the seller has to agree to payment at some future date or that the buyer should seek financing from third parties. The seller may seek financing from the buyer or third parties for purchasing goods from suppliers, to pay for labor, or to arrange for transportation and insurance (preshipment financing). The exporter may also need postshipment financing of the resulting account or accounts receivable or both (Hisrich et al., 2009; Silvester, 1995).

Competitive finance is a crucial element in export strategies, especially for small and medium-size companies. Exporters should carefully consider the type of financing required, the length of time for repayment, the loan’s effect on price and profit, and the various risks that may be associated with such financing.

In extending credit to overseas customers, it is important to recognize the following:

- Normal commercial terms range from 30 to 180 days for sales of consumer goods, industrial materials, and agricultural commodities. Custom-made or high-value capital equipment may warrant longer repayment periods.

- An allowance may have to be made for longer shipment periods than are found in domestic trade because foreign buyers are often unwilling to have the credit period start before they receive the goods.

- Customers are usually charged interest on credit periods of a year or longer and seldom on short-term credit of up to 180 days. Even though the provision of favorable financing terms makes a product more competitive, the exporter should carefully assess such financing against considerations of cost and risk of default.

1. Financing by the Exporter

1.1. Open Account

Under this arrangement, an exporter will transfer possession or ownership of the merchandise on a deferred-payment basis (payment deferred for an agreed period of time). This can be done in the case of creditworthy customers who have proven track records. In the case of customers who are not well known to the exporter, such arrangements should not be undertaken without taking out export credit insurance.

1.2. Consignment Sales

In consignment sales, importers do not pay for the merchandise until it is sold to a third party. Exporters could take out an insurance policy to cover them against risk of nonpayment.

2. Financing by the Overseas Customer

2.1. Advance Payment

The buyer can be required to pay before shipment is effected. The advance payment may comprise the entire price or an agreed-upon percentage of the purchase price. An importer may secure the advance payment through a performance guarantee provided by a third party. Export trading or export management companies, for example, often purchase goods on an advance- payment or cash-on-delivery basis, thus eliminating the need for financing. They can also use their vast international networks to help the exporter obtain credit and credit insurance.

2.2. Progress Payment

Payments can be tied to partial performance of the contract, such as production, partial shipment, and so on. This means that a mix of advance and progress payments meets the financing needs of the exporter.

3. Financing by Third Parties

3.1. Short-Term Methods

Loan secured by a foreign account receivable: An exporter can borrow money from a bank or finance company to meet its short-term working capital needs by using its foreign account receivable as collateral. In most cases, the overseas customer is not notified about the loan. As the customer makes payment to the exporter, the exporter, in turn, repays the loan to the lender. It is also possible to notify the overseas customer about the collateral and instruct the latter to pay bills directly to the lender. This may, however, call into question the financial standing of the exporter in the eyes of the overseas buyer.

An exporter can usually borrow 80 to 85 percent of the face value of its accounts receivable if the receivables are insured and the exporter and the overseas customer have good credit ratings.

Most banks are reluctant to lend against receivables that are not insured. The bank’s security is effected through assignment of the exporter’s foreign accounts receivable. Documentary collections are easier and less expensive to finance than sales on open accounts because the draft in documentary collections is a negotiable instrument (unlike open-account sales, which are accompanied by an invoice and transport documents) that can easily be sold or discounted before maturity. Although most lenders are interested in providing a loan against foreign receivables, it is not uncommon to find some that would prefer to purchase them with full or limited recourse. In both cases, most banks require insurance. (Once the receivables are sold, the exporter will be able to remove the receivables and the loan from its balance sheet.)

Trade/banker’s acceptance: In a trade acceptance, a draft drawn by the seller is accepted by the overseas customer to pay a certain sum of money on an agreed-upon date. The exporter could obtain a loan using the acceptance as collateral or discount the acceptance to a financial institution for payment. In cases in which the debt is not acknowledged in the form of a draft, the exporter could sell or discount the invoice (invoice acceptance) before maturity. In both cases, the acceptances are usually sold without recourse to the exporter, and the latter is relieved of the responsibility of collection.

A draft drawn on and accepted by a bank is called a banker’s acceptance. Once accepted, the draft becomes a primary obligation of the accepting bank to pay at maturity. This occurs in the case of documents against acceptance (documentary collection or acceptance credit), according to which payment is to be made at a specified date in the future. The bank returns the draft to the seller with an endorsement of its acceptance, guaranteeing payment to the seller (exporter) on the due date. The exporter may then sell the accepted draft at a discount to the bank or any other financial institution. The exporter could also secure a loan using the draft as collateral. The marketability of a banker’s or trade acceptance is dependent on the creditworthiness of the party accepting the draft.

Letter of credit: In addition to the acceptance credit discussed previously, the letter of credit could be an important instrument of financing exports:

- Transferable letter of credit: Using this method, the exporter transfers its rights under the credit to another party, usually a supplier, who receives payment. When the supplier presents the necessary documents to the advising bank, the supplier’s invoice is replaced by the exporter’s invoice for the full value of the original credit. The advising bank pays the supplier the value of the invoice and pays the difference to the exporter.

- Assignment of proceeds under the letter of credit: The beneficiary (exporter) may assign either the entire amount or a percentage of the proceeds of the L/C to a specified third party, usually a supplier. This allows the exporter to make purchases with limited capital by using the overseas buyer’s credit. It does not require the assent of the buyer or the buyer’s bank.

- Back-to-back letters of credit: A letter of credit is issued on the strength of another letter of credit. Such credits are issued when a supplier or subcontractor demands payment from the exporter before collections are received from the customer. The exporter remains obligated to perform under the original credit, and, if default occurs, the bank is left holding worthless collateral.

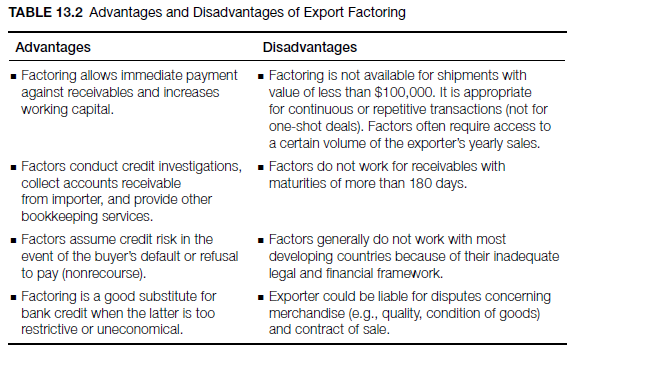

Factoring: Factoring is a continuous arrangement between a factoring concern and the exporter, whereby the factor purchases export receivables for a somewhat discounted price (usually 2 to 4 percent less than the full value). The amount of the discount depends on a number of factors, including the kind of products involved, the customer, the factoring entity, and the importing country. Factoring enables exporters to offer terms of sale on open account without assuming the credit risk. Importers also prefer factoring because by buying on open account, they forgo costly payment arrangements such as letters of credit. It also frees up their working capital. In the case of importers that have not yet established a track record, banks often will not issue letters of credit, so open-account sales may be the only available option (Klapper, 2007).

In export factoring, the exporter receives immediate payment, and the burden of collection is eliminated. Factors have ties to banks and financial institutions in other countries through networks such as Factors Chain International, which enables them to check the creditworthiness of an overseas customer, to authorize credit, and to assume financial risk.

Increases in global trade and competition have resulted in the search for alternative forms of financing to accommodate the diverse needs of customers. In highly competitive markets, concluding a successful export deal often depends on the seller’s ability to obtain trade finance at the most favorable terms for the overseas customer.

International factoring achieved another milestone during the past ten years, generating over $2.8 trillion in 2012. In the United States, the factoring industry handled about $10 billion in foreign trade ($93 billion in domestic trade) (Factors Chain International (2013). Annual Review) It is available (2012) in more than forty countries, mostly concentrated in the Americas (9 percent), Western Europe (61 percent), and Asia (27 percent). Even though export factoring has been traditionally associated with the sale of textiles and apparel, footwear, and carpets, it is now used for a host of diversified products.

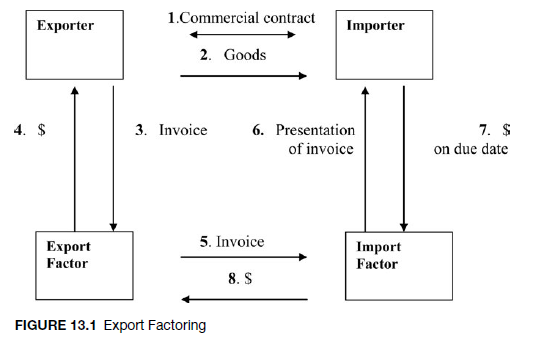

A typical export factoring procedure includes the following steps. Upon receipt of an order from an overseas customer, the exporter verifies with the factor, through its overseas affiliate, the customer’s credit standing and determines whether the factor is willing to authorize credit and to assume financial risk. If the factor’s decision is in favor of authorizing credit to the overseas customer, then the parties follow the procedure described in Figure 13.1.

Arrangements with factors are made either with recourse (exporter is liable in the event of default by buyer or other problems) or without recourse, in which case a larger discount may be required since the exporter is free of liability. (For advantages and disadvantages of this financing method, see Table 13.2).

- The exporter and importer enter into a commercial contract and agree on the terms of sale (i.e., open account).

- The exporter ships the goods to the importer.

- The exporter submits the invoice to the export factor.

- The export factor provides (cash in advance) funds to the exporter against receivables until money is collected from the importer. The exporter often receives up to 30 percent of the value of the receivables ahead of time and pays the factor interest on the money received; alternatively, the factor pays the exporter, less a commission charge, when receivables are due (or shortly thereafter). The commission often ranges between 1 and 3 percent.

- The export factor passes the invoice to the import factor for assumption of credit risk, administration, and collection of the receivables.

- The import factor presents the invoice to the importer for payment on the agreed-upon date.

- The importer pays the import factor.

- The import factor pays the export factor. In cases where the export factor advanced funds up to a certain percentage (e.g., 30 percent) of the exporter’s receivables, the remaining portion (70 percent of receivables less interest or other charges) is paid by the export factor to the exporter.

3.2. Intermediate- and Long-Term Methods

Buyer credit: Some export sales, such as those involving capital equipment, require financing terms that extend over several years. The importer may obtain credit from a bank or other financial institution to pay the exporter. The seller often cooperates in structuring the financing arrangements to make them suitable to the needs of the buyer.

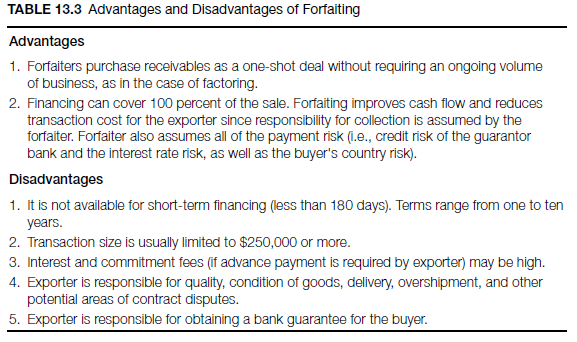

Forfaiting: Forfaiting is the practice of purchasing deferred debts arising from international sales contracts without recourse to the exporter. The exporter surrenders possession of export receivables (deferred-debt obligation from the importer), which are usually guaranteed by a bank in the importing country, by selling to a forfaiter at a discount in exchange for cash. The deferred debt may be in the form of a promissory note, bill of exchange, trade acceptance, or documentary credit, which are unconditional and easily transferable debt instruments that can be sold on the secondary market.

The origins of forfaiting date back to the 1940s, when Swiss financiers developed new ways of financing sales of West German capital equipment to Eastern Europe. Since Eastern European countries did not have enough hard currency to finance imports, they sought intermediate-term financing from their suppliers. The leading forfait houses are still located in Europe.

In a typical forfaiting transaction, the overseas customer does not have hard currency to finance the sale and wishes to purchase on credit, usually payable within one to ten years. The exporter (or exporter’s bank) contacts a forfaiter and provides the latter with the details of the proposed transaction with the overseas customer. The forfaiter evaluates the transaction and agrees to finance the deal on the basis of a certain discount rate and other conditions. The exporter then incorporates the discount into the selling price. Discount rates are fixed and based on the London Interbank Offered Rate (LIBOR), on which floating interest rates are based. The forfaiter usually requires a guarantee or aval (letter of assurance) from a bank in the importer’s country and often provides the exporter with a list of local banks that are acceptable as guarantors. The guarantee becomes quite important, especially in cases of receivables from developing countries. Once an acceptable guarantor is found, the exporter ships the goods to the buyer and endorses the negotiable instruments in favor of the forfaiter without recourse. The forfaiter then pays the exporter the discounted proceeds.

Although export factoring and forfaiting appear quite similar, there are certain differences in terms of payment terms, products involved, continuity of transaction, and overall use:

- Factors are often used to finance consumer goods, whereas forfaiters usually work with capital goods, commodities, and projects.

- Factors are used for continuous transactions, but forfaiters finance one-time deals.

- Forfaiters work with receivables from developing countries whenever they obtain an acceptable bank guarantor; factors do not finance trade with most developing countries because of the unavailability of credit information, poor credit ratings, or inadequate legal and financial frameworks.

- Factors generally work with short-term receivables, whereas forfaiters finance receivables with a maturity of more than 180 days. (See Table 13.3 for advantages and disadvantages of this financing method.)

The following are some examples of forfaiting transactions:

- The Bankers Association for Foreign Trade (BAFT) arranged with a cotton machinery company to sell more than $500,000 worth of cotton-lint-removal machinery payable eleven months from the date on the bill of lading. A Greek commercial bank issued the letter of credit, which called for acceptance drafts. Bankers Trust of New York confirmed the letter of credit, and Midland Bank undertook the forfaiting transaction.

- Morgan Grenfell Trade Finance Limited purchased receivables from U.S. exporters to Peru. The finance company required the guarantee of one of the large Peruvian banks and accepted a repayment period of up to five years.

- Morgan Grenfell also financed the down payment in cash (forfaiting) of the sale of electric turbines to Mexico, which was financed by Eximbank. The Eximbank required a 15 percent down payment.

- The Export Development Corporation (EDC) of Canada purchases accounts receivable from Canadian exporters provided the promissory notes issued by the overseas customer are guaranteed by a bank acceptable to the EDC, the transaction complies with the Canadian content requirement, and the promissory note does not exceed 85 percent of the contract price.

Export leasing: This is a financing scheme in which a third party, be it an international leasing entity or a finance firm, purchases and exports capital equipment with a view to leasing it to the importer in another country on an intermediate- to long-term basis. This arrangement is suitable for the export of capital goods. The lessor could be located in the exporting or importing country. Whether it is an operating or finance lease, the legal ownership of the asset remains with the lessor and only possession passes to the lessee. Under the operating lease, the lease rentals are not intended to amortize the capital outlay incurred by the lessor when the equipment was purchased. Instead, the capital outlay and profit are intended to be recovered through the re-leasing of the equipment and/or through its residual value on its eventual sale. It is not a method of financing the acquisition of the equipment but a lease for a specified period. The lease is reflected in the balance sheet of the lessor, not the lessee. Under the finance lease, the lease rentals are intended to amortize the capital costs of acquisition as well as to provide profit. Usually, the lessee chooses the equipment to be leased and bears the cost of maintenance and insurance. For businesses that need new equipment but lack the necessary resources or hard currency to purchase, leasing becomes an attractive option. It requires little or no down payment, and the equipment can be bought at the end of the lease agreement for a nominal price. Lease payments are tax deductible in many countries. Since such payments do not appear as liabilities in the financial statements, they preserve the lessee’s financial position and do not reduce its ability to borrow for other reasons. Other advantages of leasing are that (1) one can lease up-to-date equipment that may be too expensive to purchase, and (2) the lessee can always trade in the old equipment in the event of obsolescence and obtain new even before the end of the lease. There are, however, certain disadvantages: (1) it may attract adverse tax consequences in certain countries, and (2) the cost of leasing is often higher than other financing methods.

Source: Seyoum Belay (2014), Export-import theory, practices, and procedures, Routledge; 3rd edition.

very nice publish, i actually love this web site, carry on it

Hi there! This post couldn’t be written any better! Reading through this post reminds me of my previous room mate! He always kept talking about this. I will forward this article to him. Pretty sure he will have a good read. Thank you for sharing!