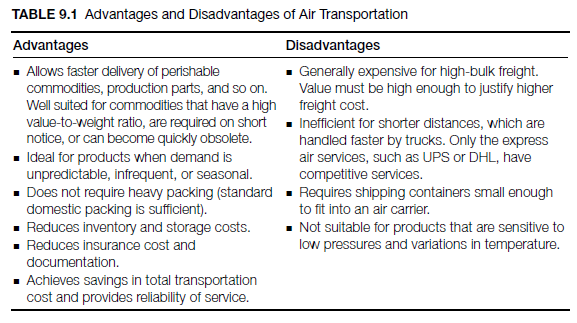

Airfreight accounts for less than 3 percent of world trade by weight and approximately 40 percent of world trade by volume. Demand for airfreight is correlated with world economic growth, fuel prices, and availability/competitiveness of surface transport options. (See Table 9.1 for advantages and disadvantages of this transportation type.)

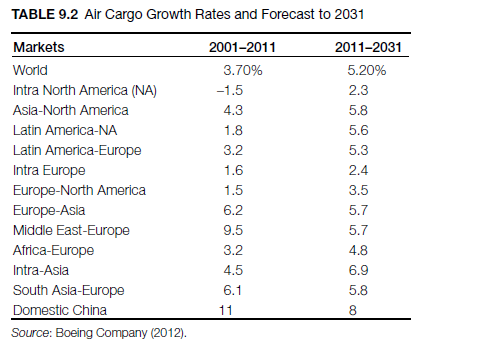

Air cargo traffic has shown slower growth since 2004 (3.7% between 2004 and 2011) compared to its historic growth trend of 6.7% (1981-2004). The major factors contributing to this slowdown include the global economic downturn of 2008 and 2009, rising fuel prices, and overall restrained consumer spending. For example, rising fuel prices have diverted air cargo to land and maritime modes, which are less sensitive to fuel costs. In spite of these challenges, Boeing forecasts that world air cargo traffic is likely to grow by 5.2 percent over the next twenty years (2011-2031) (Boeing Company, 2012). Worldwide airfreight is expected to more than double, increasing from 195 billion revenue ton kilometers (RTKs) in 2011 to 550 billion RTKs in 2031 (Table 9.2). A number of factors are likely to contribute to such growth in airfreight:

- The world economy: Global economic growth is expected to return to its long-term historic growth trend. Long-term growth rates are favorable for both advanced and developing nations. For example, GDP growth rates for African, Latin American, and Asian countries are expected to be more than 4 percent for 2011 through 2031. Oil and jet fuel prices are forecast to remain at mid-2012 levels or even decline.

- Infrastructure investment in developing countries: In view of the heavy infrastructure investment being made in many developing countries, there is a potential need for imports of heavy equipment and services. It is estimated that such imports could amount to about $17.8 billion in surface transport, sea, and airport projects in South America alone. Certain types of equipment exports to these countries, such as bulldozers, buses, or oildrilling equipment, often do not fit in a standard ocean container (Anonymous, 1998a; Reyes and Gilles, 1998).

- Just-in-time deliveries: Since many of these projects are built from supplies shipped to the sites on a just-in-time basis, delays in delivering cargo can lead to heavy financial losses or penalties for the suppliers. Such needs cannot be accommodated by using the traditional modes of carriage for heavy freight. Airfreight becomes the only viable means of moving such cargo to ensure timely delivery.

- Changes in technology: Technological changes over the past few decades have significantly altered the size and design of aircraft to handle heavy cargo. For example, the recent version of the Boeing 747 (747-8 freighter) has more cargo volume than the 747-400 and can carry more freight (even with passengers) than all-cargo versions of the previous generation of jets. The all-cargo plane has a payload capacity of about 148 tons and offers an additional 4,225 cubic feet of volume accommodating four additional main-deck pallets and three additional lower-hold pallets. Furthermore, improvements in terminal facilities in many countries have also contributed to increased speed and better handling and storage of shipments at airports, thus minimizing loss or damage to merchandise (International Perspective 9.1).

- The role of integrators and forwarders: The development of air carriers that provide integrated services (DHL, UPS) has increased the amount of air cargo. For example, UPS Sonic Air Service offers a guaranteed door-to-door service to most international destinations, regardless of size or weight limitations, within twenty-four hours. In addition, the role of forwarders as consolidators of small shipments makes it easier for shippers to send their merchandise by air without being subject to the minimum charge for small shipments. The forwarder consolidates various small shipments and tenders them to the airline in volume in exchange for a bill of lading furnished as the shipper of the cargo. The role of a forwarder is similar to that of a nonvessel-operating carrier in ocean freight.

1. Airfreight Calculations

Airfreight rates are based on a “chargeable weight” because the volume or weight that can be loaded on an aircraft is limited. The chargeable weight (CW) will be either the “actual weight” or the “volumetric weight,” whichever is the highest. It is calculated as follows:

1.1. Hypothetical example

Actual weight: Take cargo weight in pounds, divided by 2.2046 to convert the weight into

kilos = actual kilos

Volume: Multiply cargo measurements in inches divided by 366 = volume kilos

1.2. Sample shipment:

Medical equipment, with dimensions of 45 x 45 x 60 inches/Weight: 1,500 lb.

Actual weight: 1,500 lbs./2.2046 = 680 kilos

Volume weight: 45 x 45 x 60 inches/366 = 322 kilos

Freight charges would be assessed on the actual weight

IATA’s standard dimensional weight is based on 6,000 cubic centimeters per one physical kilogram (length in cm x width in cm x height in cm)/6,000 = volume kilos.

2. Air Cargo Rates

2.1. Determinants of Air Cargo Rates

Distance to the point of destination as well as weight and size of the shipment are important determinants of air cargo rates. The identity of the product (commodity description) and the provision of any special services also influence freight rates. If a product is classified under a general cargo category (products shipped frequently), a lower rate applies.

Products can also be classified under a special unit load (for shipments in approved containers) or a commodity rate (negotiated rates for merchandise not classified as general cargo). Special services such as charter flight or immediate transportation could substantially increase the freight rate.

2.2. Rate Setting

The International Air Transport Association (IATA) is the forum in which fares and rates are negotiated among member airlines. Over the past few years, such fares and rates have been set by the marketplace, and tariff conference proposals have tended to become reference points. IATA’s cargo service conferences also promote among members the negotiation of certain standards and procedures for cargo handling, documentation and procedures, shipment of dangerous goods, and so on.

2.3. International Air Express Services (Integrators)

The big carriers are under increasing competitive pressure from the integrated air service providers such as Federal Express and UPS. While the traditional carriers provide airport-to-airport service, the integrators have the added advantage of furnishing direct delivery services to customers, including customs clearance and payment of import duties at foreign destinations. Even though the strength of integrators had been in the transportation of smaller packages, they are now offering services geared to heavyweight cargo.

3. Carriage of Goods by Air

The international transportation of goods by air is governed by the original Warsaw Convention of 1929 and the amended convention of 1955. The Warsaw convention and its subsequent amendments are generally known as the Warsaw regime. Despite various efforts to modernize the Warsaw regime, it was still unable to accommodate the dynamic requirements of the airline industry and that of shippers. For example, some of its provisions were out of date, and liability limits were too low and often confusing. In view of this, member countries adopted a new treaty in 1999 (the Montreal Convention) to govern international carriage of goods by air. The treaty became effective in 2003, and as of February, 2013, 103 countries had ratified it, including the United States, all members of the European Union (EU), Australia, Canada, China, India, Japan, South Korea, and Mexico.

The Convention re-establishes urgently needed uniformity and predictability of rules relating to the international carriage of passengers, baggage, and cargo. Whilst maintaining the core provisions of the Warsaw System, which have successfully served the international air transport community for several decades, the new convention achieves the required modernization in a number of key areas. It protects passengers by introducing a two-tier liability system and by facilitating the swift recovery of proved damages without the need for lengthy litigation. The major changes introduced in the Montreal Convention include the following:

- A strict liability standard is imposed under the Montreal Convention; air carriers can be held liable without proof of fault once the goods are in their control (there are limited exceptions such as defective packing, act of war, or inherent defect of the goods). Unlike under the Warsaw regime, the party claiming damages does not have to prove negligence on the part of the carrier (Carr, 2010).

- Increased air carrier liability limits apply for proved damages (up to 113,100 Special Drawing Rights [SDRs]), and such liability can be increased if negligence is proved.

- Carriers face unlimited liability in the event of death or injury to passengers.

- There are advanced liability limits in the event of delay.

- The Convention requires modernization of transport documents (electronic airway bills and tickets).

The important aspects of the Montreal Convention are detailed in the following material.

3.1. Scope of the Convention

The convention governs the liability of the carrier while the goods are in its charge, whether at or outside an airport. It applies when the departure and destination points set out in the contract of carriage are in two countries that subscribe to the Convention. The convention applies to only those passengers ticketed for international travel.

3.2. Air Consignment Note (Air Waybill)

A consignment note (air waybill) is a document issued by the air carrier to a shipper that serves as a receipt for goods and evidence of the contract of carriage. However, it is not a document of title to the goods, as in the case of a bill of lading. The carrier requires the consignor to make out and hand over the air waybill with the goods.

One part of the air waybill (made out by consignor in three original parts) is to be signed by the carrier, which shall hand it to the consignor after the cargo has been accepted. The second part is marked for the carrier (signed by consignor), and the third one is marked for the consignee (signed by consignee and carrier). If, at the request of the consignor, the carrier makes out the air waybill, the carrier shall be deemed, subject to proof to the contrary, to have done so on behalf of the consignor.

The Montreal Convention encourages carriers to use electronic records and requires only three things to appear on the waybill that accompanies a consignment of goods: (1) the place of departure and destination; (2) an intermediate stopping place in a different state (if the places of departure and destination are in the same state); and (3) the weight of the consignment (Carr, 2010).

3.3. Liability of Carrier

The carrier is liable for damages sustained to cargo under its control up to 19 SDRs per kilo unless the shipper has declared a higher value on the waybill. Liability for baggage losses is limited to 1,131 SDRs for each passenger unless a higher value was declared. Airlines may be liable for delays up to 4,694 SDRs per passenger (Schaffer, Augusti, Dhoogie, and Earle, 2012).

3.4. Limitation of Liability

The liability of the carrier with respect to loss or damage to the goods or delay in delivery is limited to the sum specified under the Convention unless the consignor has declared a higher value and paid a supplementary charge.

3.5. Limitation of Action

The right to damages will be extinguished if an action is not brought within two years after the actual or supposed delivery of cargo. Notice of complaint (of damage) must be made within fourteen days from the date of receipt of cargo (seven days in the case of checked baggage) and, in the case of delay, twenty-one days from the actual date of delivery of cargo or baggage (Schaffer et al., 2012).

4. International Air Cargo Security

Potential risks associated with air cargo security include introduction of explosive and incendiary devices in cargo placed aboard aircraft; shipment of undeclared or undetected hazardous materials aboard aircraft; cargo crime, including theft and smuggling; and aircraft hijackings and sabotage by individuals with access to aircraft. Current aviation security regulations require that each passenger aircraft operator and indirect air carrier develop a security program for acceptance and screening of cargo to prevent or deter the carriage of unauthorized explosives. However, the volume of air cargo handled and the distributed nature of the air cargo system present significant challenges for screening and inspecting air cargo.

Presently, in the United States, about fifty air carriers transport air cargo on passenger aircraft handling cargo from nearly two million shippers per day (Elias, 2007). About 80 percent of these shippers use freight forwarders, who operate about 10,000 facilities across the country. Analysts warn that the cost of screening every piece of air cargo that enters the shipping system in a bid to prevent terror gangs from downing airliners might bankrupt international shipping companies and hobble the already weakened airlines and still wouldn’t provide comprehensive protection. However, efforts are being made to increase airline security without putting undue financial burden on the private sector.

Security guidelines are constantly changing in view of technological developments as well as the unpredictable nature of terrorism. Furthermore, security requirements are different for cargo shipped on freighters and for cargo shipped on passenger aircraft.

The U.S. Transportation Security Administration (TSA) (part of the U.S. Department of Homeland Security) secures the nation’s airports and screens all commercial airline passengers and baggage. The air cargo division of the TSA is responsible for the security of the air cargo supply chain. TSA uses a multilayered approach that includes vetting companies that ship and transport cargo on passenger planes to ensure that they meet TSA security standards, establishing a system to enable Certified Cargo Screening Facilities (CCSFs) to physically screen cargo using approved screening methods and technologies, employing random and risk-based assessment to identify high-risk cargo that requires increased scrutiny, and inspecting industry compliance with security regulations through the deployment of TSA inspectors (TSA, 2012).

A number of programs have been introduced to enhance air cargo security.

- Customs-Trade Partnership Against Terrorism (C-TPAT): C-TPAT is a partnership of more than 10,000 importers, freight forwarders, carriers, and other entities. It establishes clear supply-chain security criteria for members to meet and in return provides incentives and benefits such as expedited processing. When they join the antiterror partnership, companies sign an agreement to work with Customs and Border Protection (CBP) to protect the supply chain, identify security gaps, and implement specific security measures and best practices. Additionally, partners provide CBP with a security profile outlining the specific security measures the company has in place. C-TPAT members are considered low risk and are therefore less likely to be examined. This designation is based on a company’s past compliance history and security profile and on the validation of a sample international supply chain.

- Air Cargo Advanced Screening (ACAS): Airlines send manifest data of inbound cargo to CBP several hours before departure. By analyzing these data in advance, TSA and CBP have a fast and efficient way to screen vast amounts of cargo and to zero in quickly on the precise items requiring further scrutiny. ACAS may request additional information or require the air carrier or its authorized representative to screen or hold identified shipments. Screening requests from ACAS require the air carrier or its authorized representative to screen identified shipments according to current TSA Standard Security Programs. It targets high-risk shipments for enhanced screening (TSA, 2012).

- Certified Cargo Screening Program (CCSP): This program requires air carriers to screen 100 percent of all cargo aboard international inbound passenger flights. The law requires the Department of Homeland Security to establish a system to screen all cargo transported on passenger aircraft at a level “commensurate” with the level of security used for checked baggage. The program was designed to enable TSA-vetted, -validated, and -certified facilities to screen air cargo prior to delivering the cargo to the air carrier. Each facility that successfully completes the TSA certification process (include an onsite assessment of the facility) will be designated a Certified Cargo Screening Facility (CCSF). CCSFs must adhere to TSA-mandated security standards, including the employment of secure chain-of-custody methods to establish and maintain the security of screened cargo throughout the supply chain. TSA will certify only those facilities that demonstrate adherence to these requirements through the TSA certification process.

- Indirect Air Carrier Program: An Indirect Air Carrier (IAC) is any person or entity within the United States not in possession of a Federal Aviation Administration air carrier operating certificate that undertakes to engage indirectly in air transportation of property and that uses for all or any part of such transportation the services of a passenger air carrier. Each Indirect Air Carrier must adopt and carry out a security program that meets current TSA requirements. The Indirect Air Carrier Regional Compliance Coordinators are responsible for the application process for freight forwarders working to become classified as Indirect Air Carriers. These coordinators complete annual renewals for current Indirect Air Carriers and provide assistance with program compliance.

- International collaboration: TSA’s efforts to harmonize activities with foreign partners will increase global air cargo security and reduce burdens on trade. TSA’s agreements with the European Commission as well as with Canada, Australia, and European Union member states, signed in 2008, will facilitate common and practical solutions to air cargo screening. This harmonization will contribute greatly to achieving the 100 percent screening requirement of the Recommendations of the 9/11 Commission Act, 2007.

Source: Seyoum Belay (2014), Export-import theory, practices, and procedures, Routledge; 3rd edition.

It is the best time to make some plans for the longer term and it is time to be happy. I’ve read this submit and if I could I want to recommend you some interesting issues or tips. Perhaps you could write next articles referring to this article. I desire to read more things about it!