Each product can be related to other products to ensure that a firm is offering and marketing the optimal set of products.

1. THE PRODUCT HIERARCHY

The product hierarchy stretches from basic needs to particular items that satisfy those needs. We can identify six levels of the product hierarchy, using life insurance as an example:

- Need family—The core need that underlies the existence of a product family. Example: security.

- Product family—All the product classes that can satisfy a core need with reasonable effectiveness. Example: savings and income.

- Product class—A group of products within the product family recognized as having a certain functional coherence, also known as a product category. Example: financial instruments.

- Product line—A group of products within a product class that are closely related because they perform a similar function, are sold to the same customer groups, are marketed through the same outlets or channels, or fall within given price ranges. A product line may consist of different brands, a single family brand, or an individual brand that has been line extended. Example: life insurance.

- Product type—A group of items within a product line that share one of several possible forms of the product. Example: term life insurance.

- Item (also called stock-keeping unit or product variant)—A distinct unit within a brand or product line distinguishable by size, price, appearance, or some other attribute. Example: Prudential renewable term life insurance.

2. PRODUCT SYSTEMS AND MIXES

A product system is a group of diverse but related items that function in a compatible manner.49 For example, the extensive iPod product system includes headphones and headsets, cables and docks, armbands, cases, power and car accessories, and speakers. A product mix (also called a product assortment) is the set of all products and items a particular seller offers for sale.

A product mix consists of various product lines. NEC’s (Japan) product mix consists of communication products and computer products. Michelin has three product lines: tires, maps, and restaurant-rating services. At Northwestern University, separate academic deans oversee the schools of medicine, law, business, engineering, music, speech, journalism, and liberal arts, among others.

A company’s product mix has a certain width, length, depth, and consistency. These concepts are illustrated in Table 13.2 for selected Procter & Gamble consumer products.

- The width of a product mix refers to how many different product lines the company carries. Table 13.2 shows a product mix width of five lines. (In fact, P&G produces many additional lines.)

- The length of a product mix refers to the total number of items in the mix. In Table 13.2, it is 20. We can also talk about the average length of a line. We obtain this by dividing the total length (here 20) by the number of lines (here 5), for an average product line length of 4.

- The depth of a product mix refers to how many variants are offered of each product in the line. If Tide came in two scents (Clean Breeze and Regular), two formulations (liquid and powder), and with two additives (with or without bleach), it would have a depth of eight because there are eight distinct variants.50 We can calculate the average depth of P&G’s product mix by averaging the number of variants within the brand groups.

- The consistency of the product mix describes how closely related the various product lines are in end use, production requirements, distribution channels, or some other way. P&G’s product lines are consistent in that they are consumer goods that go through the same distribution channels. The lines are less consistent in the functions they perform for buyers.

These four product mix dimensions permit the company to expand its business in four ways. It can add new product lines, thus widening its product mix. It can lengthen each product line. It can add more product variants to each product and deepen its product mix. Finally, a company can pursue more product line consistency. To make these product and brand decisions, marketers can conduct product line analysis.

3. PRODUCT LINE ANALYSIS

In offering a product line, companies normally develop a basic platform and modules that can be added to meet different customer requirements and lower production costs. Car manufacturers build cars around a basic platform. Homebuilders show a model home to which buyers can add additional features. Product line managers need to know the sales and profits of each item in their line to determine which items to build, maintain, harvest, or divest.51 They also need to understand each product line’s market profile and image.52

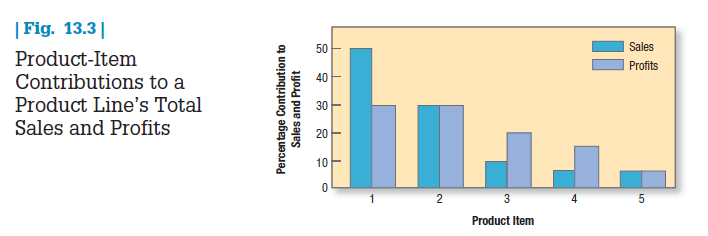

SALES AND PROFITS Figure 13.3 shows a sales and profit report for a five-item product line. The first item accounts for 50 percent of total sales and 30 percent of total profits. The first two items account for 80 percent of total sales and 60 percent of total profits. If these two items were suddenly hurt by a competitor, the line’s sales and profitability could collapse. These items must be carefully monitored and protected. At the other end, the last item delivers only 5 percent of the product line’s sales and profits. The product line manager may consider dropping this item unless it has strong growth potential.

Every company’s product portfolio contains products with different margins. Supermarkets make almost no margin on bread and milk, reasonable margins on canned and frozen foods, and better margins on flowers, ethnic food lines, and freshly baked goods. Companies should recognize that different items will allow for different margins and respond differently to changes in level of advertising.53

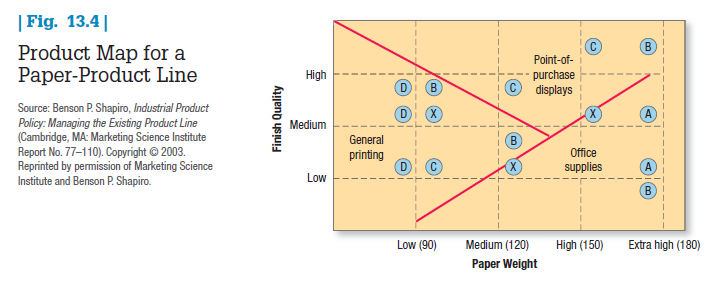

MARKET PROFILE AND IMAGE The product line manager must review how the line is positioned against competitors’ lines. Consider paper company X with a paperboard product line.54 Two paperboard attributes are weight and finish quality. Paper is usually offered at standard levels of 90, 120, 150, and 180 weights. Finish quality is offered at low, medium, and high levels.

The product map in Figure 13.4 shows the location of the various product line items of company X and four competitors, A, B, C, and D. Competitor A sells two product items in the extra-high weight class ranging from medium to low finish quality. Competitor B sells four items that vary in weight and finish quality. Competitor C sells three items in which the greater the weight, the greater the finish quality. Competitor D sells three items, all lightweight but varying in finish quality. Company X offers three items that vary in weight and finish quality.

The product map also shows which competitors’ items are competing against company X’s items. For example, company X’s low-weight, medium-quality paper competes against competitor D’s and B’s papers, but its high- weight, medium-quality paper has no direct competitor. The map also reveals possible locations for new items. No manufacturer offers a high-weight, low-quality paper. If company X estimates a strong unmet demand and can produce this paper at low cost and price it accordingly, it could consider adding it to its line.

Another benefit of product mapping is that it identifies market segments. Figure 13.4 shows the types of paper, by weight and quality, preferred by the general printing industry, the point-of-purchase display industry, and the office supply industry. The map shows that company X is well positioned to serve the needs of the general printing industry but less effective in serving the other two markets.

Product line analysis provides information for two key decision areas: product line length and product mix pricing.

4. PRODUCT LINE LENGTH

Company objectives influence product line length. One objective is to create a product line to induce up-selling. Mercedes C-Class plays a critical function as an entry point to the brand. As one industry analyst notes: “The C-Class is critical for the luxury race because it creates the most amount of volume for Benz. It also opens the Benz brand to potential future buyers by catching them while they’re young with the hopes that they upgrade as they get more affluent and older.”55

A different objective is to create a product line that facilitates cross-selling: Hewlett-Packard sells printers as well as computers. Still another is to protect against economic ups and downs: Electrolux offers white goods such as refrigerators, dishwashers, and vacuum cleaners under different brand names in the discount, middle-market, and premium segments, in part as a hedge when the economy moves up or down. Companies seeking high market share and market growth will generally carry longer product lines. Those emphasizing high profitability will carry shorter lines consisting of carefully chosen items.

Product lines tend to lengthen over time. Excess manufacturing capacity puts pressure on the product line manager to develop new items. The sales force and distributors also lobby for a more complete product line to satisfy customers. But as items are added, costs rise for design and engineering, inventory carrying, manufacturing changeover, order processing, transportation, and new-item promotions. Eventually, top management may stop development because of insufficient funds or manufacturing capacity. A pattern of product line growth followed by massive pruning may repeat itself many times. Increasingly, consumers are growing weary of dense product lines, overextended brands, and feature-laden products (see “Marketing Insight: When Less Is More”).56 A company lengthens its product line in two ways: line stretching and line filling.

LINE STRETCHING Every company s product line covers a certain part of the total possible range. For example, Mercedes automobiles are located in the upper price range of the automobile market. Line stretching occurs when a company lengthens its product line beyond its current range, whether down-market, up-market, or both ways.

Down-Market Stretch A company positioned in the middle market may want to introduce a lower-priced line for any of three reasons:

- The company may notice strong growth opportunities. Mass retailers such as Walmart, Target, and others attract a growing number of shoppers who want value-priced goods.

- The company may wish to tie up lower-end competitors who might otherwise try to move up-market. If the company has been attacked by a low-end competitor, it often decides to counterattack by entering the low end of the market.

- The company may find the middle market stagnating or declining.

Marketers face a number of naming choices in deciding to move a brand down-market:

- Use the parent brand name on all its offerings. Sony has used its name on products in a variety of price tiers.

- Introduce lower-priced offerings using a sub-brand name, such as P&G’s Charmin Basic and Bounty Basic.

- Introduce the lower-priced offerings under a different name, such as the Gap’s Old Navy brand. This strategy is expensive to implement and means brand equity will have to be built from scratch, but the equity of the parent brand name is protected.

Moving down-market carries risks. In one classic example, when Kodak introduced Kodak Funtime Film to counter lower-priced brands, it did not price it low enough to match competitors. It also found some of its regular customers buying Funtime, so it was cannibalizing its core brand. Kodak withdrew the product and may have also lost some of its quality image in the process. P&G also introduced Tide Basic in test markets—priced lower but also lacking some of the latest detergent technology of its famous parent brand—and decided against rolling it out.57

On the other hand, Mercedes successfully introduced its C-Class cars at $30,000 without injuring its ability to sell other Mercedes cars for $100,000. John Deere introduced a lower-priced line of lawn tractors called Sabre from John Deere, while still selling its more expensive tractors under the John Deere name. In these cases, consumers may have been better able to compartmentalize the different offerings and understand the functional differences between them.58

Up-Market Stretch Companies may wish to enter the high end of the market to achieve more growth, realize higher margins, or simply position themselves as full-line manufacturers. Many markets have spawned surprising upscale segments: Starbucks in coffee, Haagen-Dazs in ice cream, and Evian in bottled water. The leading Japanese auto companies each introduced a highly successful upscale automobile nameplate: Toyota’s Lexus, Nissan’s Infiniti, and Honda’s Acura. They invented entirely new names because consumers might not have given the brand “permission” to stretch upward when those lines were first introduced.

Other companies have included their own names in moving up-market. Gallo sells Gallo Family Vineyards (priced at $10 to $30 a bottle) with a hip, younger image to compete in the premium wine segment. General Electric introduced the GE Profile brand for its large-appliance offerings in the upscale market. Some brands have used modifiers to signal a quality improvement, such as Ultra Dry Pampers, Extra Strength Tylenol, and Power Pro Dustbuster Plus.

Two-Way Stretch Companies serving the middle market might stretch their line in both directions. Robert Mondavi Winery, now owned by Constellation Brands, sells $35 bottles of wines as the first premium “New World” wine, but it also sells $125 bottles of Mondavi Reserve at high-end wineries, restaurants, and vineyards and through direct order, as well as $11 bottles of Woodbridge created during the grape oversupply of the mid-1990s. Purina Dog Food has stretched up and down to create a product line differentiated by benefits to dogs, breadth of varieties, ingredients, and price:

- Pro Plan ($38.99/18 lb. bag)—helps dogs live long and healthy lives with high-quality ingredients (real meat, fish, and poultry)

- Purina ONE ($22.99/16.5 lb. bag)—meets dogs’ changing and unique nutritional needs and provides superpremium nutrition for good health

- Purina Dog Chow ($12.24/18.5 lb. bag)—provides dogs with complete nutrition to build, replenish, and repair at each life stage

- Alpo by Purina ($8.69/17.6 lb. bag)—offers beef, liver, and cheese flavor combinations and three meaty varieties

LINE FILLING A firm can also lengthen its product line by adding more items within the present range. Motives for line filling include reaching for incremental profits, satisfying dealers who complain about lost sales because of items missing from the line, utilizing excess capacity, trying to become the leading full-line company, and plugging holes to keep out competitors. Consider BMW.59

BMW AG In four years, BMW has morphed from a one-brand, five-model carmaker into a powerhouse with three brands, 14 “Series,” and roughly 30 distinct models. Not only has the carmaker expanded its product range downward with MINI Coopers and its compact 1-series models, but it has also built it upward with Rolls-Royce and filled the gaps in between with its X1, X3, X5, and X6 sports activity vehicles, Z4 roadsters, and a 6-series coupe. The company has used line filling successfully to boost its appeal to the rich, the super-rich, and the hope-to-be-rich, all without departing from its pure premium positioning. BMW has also built a clear brand migration strategy within its product line. It would like to move customers up from a 1-series or 3-series vehicle to a 5-series and eventually even a 7-series.

Line filling is overdone if it results in cannibalization and customer confusion. The company needs to differentiate each item in the consumer’s mind with a just-noticeable difference. According to Weber’s law, customers are more attuned to relative than to absolute difference.60 They will perceive the difference between boards 2 and 3 feet long and boards 20 and 30 feet long, but not between boards 29 and 30 feet long. The proposed item should also meet a market need and not be added simply to satisfy an internal need. The infamous Edsel automobile, on which Ford lost $350 million in the late 1950s, met Ford’s internal positioning need for a car between its Ford and Lincoln lines, but not the market’s needs.

LINE MODERNIZATION, FEATURING,AND PRUNING Product lines regularly need to be modernized. The question is whether to overhaul the line piecemeal or all at once. A piecemeal approach allows the company to see how customers and dealers take to the new style. It is also less draining on the company’s cash flow, but it lets competitors see changes and start redesigning their own lines.

In rapidly changing markets, modernization is continuous. Companies plan improvements to encourage customer migration to higher-value, higher-price items. Microprocessor companies such as Intel and AMD and software companies such as Microsoft and Oracle continually introduce more advanced versions of their products. Marketers want to time improvements so they do not appear too early (damaging sales of the current line) or too late (giving the competition time to establish a strong reputation).61

The product line manager typically selects one or a few items in the line to feature. Best Buy will announce a special low-priced big-screen TV to attract customers. At other times, managers will feature a high-end item to lend prestige to the product line. Sometimes a company finds one end of its line selling well and the other end selling poorly.

It may try to boost demand for slower sellers, especially if a factory is idled by lack of demand, but it could be counterargued that the firm should promote strong sellers rather than prop up weak ones. Nike’s Air Force 1 basketball shoe, introduced in the 1980s, is a billion-dollar brand that is still a consumer and retailer favorite and a moneymaker for the company thanks to collectable styles and tight supplies. Since their introduction, the shoes have been designed or inspired by many celebrities and athletes.62

Using sales and cost analysis, product line managers must periodically review the line for deadwood that depresses profits.63 One study found that for a big Dutch retailer, a major assortment reduction led to a shortterm drop in category sales, caused mainly by fewer category purchases by former buyers, but it also attracted new category buyers who partially offset the losses.64

Multi-brand companies all over the world try to optimize their brand portfolios. This often means focusing on core brand growth and concentrating resources on the biggest and most established brands. Hasbro has designated a set of core toy brands to emphasize in its marketing, including GI Joe, Transformers, and My Little Pony. Procter & Gamble’s “back to basics” strategy concentrated on brands with more than $1 billion in revenue, such as Tide, Crest, Pampers, and Pringles. Every product in a product line must play a role, as must any brand in the brand portfolio.65

VOLKSWAGEN Volkswagen has four different core brands of particular importance in its European portfolio. Initially, Audi and Seat had a sporty image and VW and Skoda had a family-car image. Audi and VW were in a higher price-quality tier than Skoda and Seat, which had spartan interiors and utilitarian engine performance. To reduce costs, streamline part/systems designs, and eliminate redundancies, Volkswagen upgraded the Seat and Skoda brands, which captured market share with splashy interiors, a full array of safety systems, and reliable power trains. The danger, of course, is that by borrowing from its upper-echelon Audi and Volkswagen products, Volkswagen could dilute their cachet. Frugal European consumers may convince themselves that a Seat or Skoda is almost identical to its VW sister, at several thousand euros less.

5. MARKETING INSIGHT When Less Is More

With thousands of new products introduced each year, consumers find it ever harder to navigate store aisles. One study found the average shopper spent 40 seconds or more in the supermarket soda aisle, compared with 25 seconds six or seven years ago.

Although consumers may think greater product variety increases their likelihood of finding the right product for them, the reality is often different. One study showed that although consumers expressed greater interest in shopping a larger assortment of 24 flavored jams than a smaller assortment of 6, they were 10 times more likely to actually make a selection when given the smaller assortment. Presented with too many options, people “choose not to choose,” even if it may not be in their best interests.

Similarly, if product quality in an assortment is high, consumers actually prefer fewer choices. Those with well-defined preferences may benefit from more-differentiated products that offer specific benefits, but others may experience frustration, confusion, and regret. Product proliferation has another downside. Constant product changes and introductions may nudge customers into reconsidering their choices and perhaps switching to a competitor’s product.

Some companies are getting the message. When Procter & Gamble went from 20 different kinds of Head & Shoulders to 15, sales for the brand increased by 10 percent. Smart marketers realize it’s not just product lines making consumer heads spin—many products themselves are too complicated. Technology marketers need to be especially sensitive to the problems of information overload. The launch of the HTC One smartphone succeeded in part because the company adopted a “less is more” approach instead of just adding features.

Sources: John Davidson, “One Classic Example of When Less Is More,” Financial Review, April 9, 2013; Carolyn Cutrone, “Cutting Down on Choice Is the Best Way to Make Better Decisions,” Business insider, January 10, 2013; Dimitri Kuksov and J. Miguel Villas-Boas, “When More Alternatives Lead to Less Choice,” Marketing Science, 29 (May/June 2010), pp. 507-24; Kristin Diehl and Cait Poynor, “Great Expectations?! Assortment Size, Expectations, and Satisfaction,” Journal of Marketing Research 46 (April 2009), pp. 312-22; Joseph P Redden and Stephen J. Hoch, “The Presence of Variety Reduces Perceived Quantity,” Journal of Consumer Research 36 (October 2009), pp. 406-17; Alexander Chernev and Ryan Hamilton, “Assortment Size and Option Attractiveness in Consumer Choice Among Retailers,” Journal of Marketing Research 46 (June 2009), pp. 410-20; Richard A. Briesch, Pradeep K. Chintagunta, and Edward J. Fox, “How Does Assortment Affect Grocery Store Choice,” Journal of Marketing Research 46 (April 2009), pp. 176-89; Susan M. Broniarczyk, “Product Assortment,” Curt P Haugtvedt, Paul M. Herr, and Frank R. Kardes, eds., Handbook of Consumer Psychology (New York: Taylor & Francis, 2008), pp. 755-79.

6. PRODUCT MIX PRICING

Marketers must modify their price-setting logic when the product is part of a product mix. In product mix pricing, the firm searches for a set of prices that maximizes profits on the total mix. The process is challenging because the various products have demand and cost interrelationships and are subject to different degrees of competition. We can distinguish six situations calling for product-mix pricing: product line pricing, optional-feature pricing, captive-product pricing, two-part pricing, by-product pricing, and product-bundling pricing.

PRODUCT LINE PRICING Companies normally develop product lines rather than single products, so they introduce price steps. A men’s clothing store might carry men’s suits at three price levels: $300, $600, and $900, which customers associate with low, average, and high quality. The seller’s task is to establish perceived quality differences that justify the price differences.66

OPTIONAL-FEATURE PRICING Many companies offer optional products, features, and services with their main product. The 2013 Subaru Outback 2.5i was available in five trim levels. Premium trim additional features included an eight-way power driver’s seat, windshield wiper de-icer, leather-wrapped steering wheel, and 17-inch aluminum wheels; the more luxurious Limited trim added even more features, including perforated leather, dualzone automatic climate control, heated front seats, heated side mirrors, and a Harman/Kardon audio system with satellite radio.67

Pricing options is a sticky problem because companies must decide which to include in the standard price and which to offer separately. Many restaurants price their beverages high and their food low. The food revenue covers costs, and the beverages—especially liquor—produce the profit. This explains why servers often press hard to get customers to order drinks. Other restaurants price their liquor low and food high to draw in a drinking crowd.

CAPTIVE-PRODUCT PRICING Some products require the use of ancillary or captive products. Manufacturers of razors often price them low and set high markups on razor blades. Movie theaters and concert venues often make more from concessions and merchandise sales than from ticket receipts.68 AT&T may give a cell phone for free if the person commits to buying two years of phone service.

If the captive product is priced too high in the aftermarket, however, counterfeiting and substitutions can erode sales. Consumers now can buy cartridge refills for their printers from discount suppliers and save 20 percent to 30 percent off the manufacturer’s price. Hewlett-Packard has attempted to strike the right balance in its printer pricing, though changes in the marketing environment are upending its well-honed profit machine.69

HEWLETT-PACKARD In 1996, Hewlett-Packard (HP) began drastically cutting prices on its printers, by as much as 60 percent in some cases. The company could afford to make these cuts because over the life of the product customers typically spend twice as much on replacement ink cartridges, toner, and specialty paper as on the printer, and inkjet supplies typically carry 45 percent to 60 percent profit margins. As the price dropped, printer sales rose, and so did aftermarket sales. Over the next decade, with a market share above 40 percent, the printer division was a highly profitable cash cow for the company. But with more consumers using tablets and smart phones and sharing images and information via cloud computing, HP’s bigger challenge now is countering the continuing decline in sales of PCs. Lower PC sales have meant lower printer sales and a steady drop in profit margin and revenue in recent years.

TWO-PART PRICING Service firms engage in two-part pricing, consisting of a fixed fee plus a variable usage fee. Cell phone users may have to pay a minimum monthly fee plus charges for calls that exceed their allotted minutes. Amusement parks charge an admission fee plus fees for rides over a certain minimum. The service firm faces a problem similar to captive-product pricing—namely, how much to charge for the basic service and how much for the variable usage. The fixed fee should be low enough to induce purchase; profit can then come from the usage fees.

BY-PRODUCT PRICING The production of certain goods—meats, petroleum products, and other chemicals—often yields by-products that should be priced on their value. Any income earned on the by-products will make it easier for the company to charge a lower price on its main product if competition forces it to do so. Formed in 1855, Australia’s CSR was originally named Colonial Sugar Refinery and forged its early reputation as a sugar company. The company began to sell by-products of its sugar cane; waste sugar cane fiber was used to manufacture wallboard. Today, through product development and acquisition, the renamed CSR has become one of the top 10 companies in Australia selling building and construction materials.

PRODUCT-BUNDLING PRICING Sellers often bundle products and features.70 Pure bundling occurs when a firm offers its products only as a bundle. Providers of aftermarket products for automobiles increasingly are bundling their offerings in customizable three-in-one and four-in-one programs, especially second-tier products such as tire-and-wheel protection and paintless dent repair.71 A talent agency might insist that a “hot” actor can be signed to a film only if the film company also accepts other talent the agency represents such as directors or writers. This is a form of tied-in sales.

In mixed bundling, the seller offers goods both individually and in bundles, normally charging less for the bundle than if the items were purchased separately. A theater will price a season subscription lower than the cost of buying all the performances separately. Customers may not have planned to buy all the components, so savings on the price bundle must be enough to induce them to buy it.72

Some customers want less than the whole bundle in exchange for a lower price.73 These customers ask the seller to “unbundle” or “rebundle” its offer. If a supplier saves $100 by not supplying unwanted delivery and reduces the customer’s price by $80, it has kept the customer happy while increasing its profit by $20. “Marketing Memo: Product-Bundle Pricing Considerations” offers a few tips.

7. CO-BRANDING AND INGREDIENT BRANDING

CO-BRANDING Marketers often combine their products with products from other companies in various ways. In co-branding—also called dual branding or brand bundling—two or more well-known brands are combined into a joint product or marketed together in some fashion.

One form of co-branding is same-company co-branding, as when General Mills advertises Trix cereal and Yoplait yogurt. Another form is joint-venture co-branding, such as General Electric and Hitachi lightbulbs in Japan or the Citi Platinum Select AAdvantage Visa Signature credit card in which three different parties are involved. There is multiple-sponsor co-branding, such as Taligent, a one-time technological alliance of Apple, IBM, and Motorola. Finally, there is retail co-branding in which two retail establishments use the same location to optimize space and profits, such as jointly owned Pizza Hut, KFC, and Taco Bell restaurants.

The main advantage of co-branding is that a product can be convincingly positioned by virtue of the multiple brands. Co-branding can generate greater sales from the existing market and open opportunities for new consumers and channels. It can also reduce the cost of product introduction because it combines two well-known images and speeds adoption. And co-branding may be a valuable means to learn about consumers and how other companies approach them. Companies in the automotive industry have reaped all these benefits.

The potential disadvantages of co-branding are the risks and lack of control in becoming aligned with another brand in consumers’ minds. Consumer expectations of co-brands are likely to be high, so unsatisfactory performance could have negative repercussions for both brands. If the other brand enters a number of co-branding arrangements, overexposure may dilute the transfer of any association. It may also result in a lack of focus on existing brands. Consumers may feel less sure of what they know about the brand.74

For co-branding to succeed, the two brands must separately have brand equity—adequate brand awareness and a sufficiently positive brand image. The most important requirement is a logical fit between the two brands, to maximize the advantages of each while minimizing disadvantages. Consumers are more apt to perceive co-brands favorably if they are complementary and offer unique quality, rather than being overly similar and redundant.

Managers must enter co-branding ventures carefully, looking for the right fit in values, capabilities, and goals and an appropriate balance of brand equity. There must be detailed plans to legalize contracts, make financial arrangements, and coordinate marketing programs. As one executive at Nabisco put it, “Giving away your brand is a lot like giving away your child—you want to make sure everything is perfect.” Financial arrangements between brands vary; one common approach is for the brand more deeply invested in the production process to pay the other a licensing fee and royalty.

Brand alliances require a number of decisions.75 What capabilities do you not have? What resource constraints do you face (people, time, money)? What are your growth goals or revenue needs? Ask whether the opportunity is a profitable business venture. How does it help maintain or strengthen brand equity? Is there any risk of diluting brand equity? Does the opportunity offer extrinsic advantages such as learning opportunities?

INGREDIENT BRANDING Ingredient branding is a special case of co-branding.76 It creates brand equity for materials, components, or parts that are necessarily contained within other branded products. For host products whose brands are not that strong, ingredient brands can provide differentiation and important signals of quality.77

Successful ingredient brands include Dolby noise reduction technology, GORE-TEX water-resistant fibers, and Scotchgard fabrics. Vibram is the world leader in high-performance rubber soles for outdoor, work, military, recreation, fashion, and orthopedic shoes. Look under your shoe and you may find Vibram soles—they are used by a wide range of footwear manufacturers, including The North Face, Saucony, Timberland, Lacoste, L.L. Bean, Wolverine, Rockport, Columbia, Nike, and Frye.78

An interesting take on ingredient branding is self-branded ingredients that companies advertise and even trademark.79 Westin Hotels advertises its own “Heavenly Bed”—a critically important ingredient to a guest’s good night’s sleep. The brand has been so successful that Westin now sells the bed, pillows, sheets, and blankets via an online catalog, along with other “Heavenly” gifts, bath products, and even pet items. The success of the bed has also created a halo for the Westin brand as a whole. Heavenly Bed enthusiasts are more likely to rate other aspects of their room or stay as more positive.80 If it can be done well, using selfbranded ingredients makes sense because firms have more control over them and can develop them to suit their purposes.

Ingredient brands try to create enough awareness and preference for their product so consumers will not buy a host product that doesn’t contain it. DuPont has introduced a number of innovative products, such as Corian® solid-surface material, for use in markets ranging from apparel to aerospace. Many of its products, such as Tyvek® house wrap, Teflon® non-stick coating, and Kevlar® fiber, became household names as ingredient brands in consumer products manufactured by other companies. Since 2004, DuPont has introduced more than 5,000 new products and received more than 2,400 new patents.81

Many manufacturers make components or materials that enter final branded products but lose their individual identity. One of the few companies that avoided this fate is Intel. Intel’s consumer-directed brand campaign convinced many personal computer buyers to buy only brands with “Intel Inside.” As a result, major PC manufacturers—Dell, HP, Lenovo—typically purchase their chips from Intel at a premium price rather than buy equivalent chips from an unknown supplier.

What are the requirements for successful ingredient branding?82

- Consumers must believe the ingredient matters to the performance and success of the end product. Ideally, this intrinsic value is easily seen or experienced.

- Consumers must be convinced that not all ingredient brands are the same and that the ingredient is superior.

- A distinctive symbol or logo must clearly signal that the host product contains the ingredient. Ideally, this symbol or logo functions like a “seal” and is simple and versatile, credibly communicating quality and confidence.

- A coordinated “pull” and “push” program must help consumers understand the advantages of the branded ingredient. Channel members must offer full support such as consumer advertising and promotions and— sometimes in collaboration with manufacturers—retail merchandising and promotion programs.

8. MARKETING MEMO Product-Bundle Pricing Considerations

As promotional activity increases on individual items in the bundle, buyers perceive less savings from the bundle and are less apt to pay for it. Research suggests the following guidelines for implementing a bundling strategy:

- Don’t promote individual products in a package as frequently or for as little as the bundle. The bundle price should be much lower than the sum of individual products or the consumer will not perceive its attractiveness.

- If you still want to promote individual products, choose a single item in the mix. Another option is to alternate promotions to avoid running conflicting ones.

- If you offer large rebates on individual products, do so with discretion and make them the absolute exception. Otherwise, the consumer uses the price of individual products as an external reference for the bundle, which then loses value.

- Consider how experienced and knowledgeable your customer is. More knowledgeable customers may be less likely to need or want bundled offerings and prefer the freedom to choose components individually.

- Make sure the value of the bundle is easily understood. Bundles can streamline choices and make it easier for a consumer to appreciate different sets of benefits.

- Remember costs play a role. If marginal costs for the products are low—such as for proprietary software components that can be easily copied and distributed—a bundling strategy can be preferable to a pure component strategy where each component is purchased separately.

- Firms with single products that bundle their products together to compete against a multiproduct firm may not be successful if a price war ensues.

Sources: Dina Gerdeman, “Product Bundling Is a Smart Strategy—But There’s a Catch,” Forbes, January 18, 2013; Timothy P. Derdenger and Vineet Kumar, “The Dynamic Effects of Bundling as a Product Strategy,” Marketing Science 32 (November-December 2013), pp. 827-59; Aaron Brough and Alexander Chernev, “When Opposites Detract: Categorical Reasoning and Subtractive Valuations of Product Combinations” Journal of Consumer Research 39 (August 2012), pp. 399-414; Amiya Basu and Padmal Vitharana, “Impact of Customer Knowledge Heterogeneity on Bundling Strategy,” Marketing Science 28 (July-August 2009), pp. 792-801; Bikram Ghosh and Subramanian Balachnadar, “Competitive Bundling and Counterbundling with Generalist and Specialist Firms,” Management Science 53 (January 2007), pp. 159-68.

Source: Kotler Philip T., Keller Kevin Lane (2015), Marketing Management, Pearson; 15th Edition.

Hi! This post could not be written any better! Reading through this post reminds me of my previous room mate! He always kept talking about this. I will forward this write-up to him. Fairly certain he will have a good read. Thanks for sharing!