Sales management’s next task is to measure actual performance. Emphasis in this phase of control, in other words, shifts to gathering performance information. It is necessary to define information needs, determine the information sources, and collect the information.

The choice of performance standards dictates the information needed. However, with increasingly sophisticated management information systems, the choice of performance standards is based as much on information availability as on the desire to use certain standards. It is good practice to review periodically the sales performance standards in use and the availability of other information that might permit use of different or additional standards.

There are two basic sources of performance information: sales and expense records and reports of various sorts. Almost every company has a wealth of data in its internal sales and expense records, but this information frequently requires reworking, or reprocessing, before it is useful for sales control purposes. Reclassified according to sales management’s information needs, sales and expense data contribute to the determination and measurement of actual performances.

Among the reports sales management has available are those from sales personnel and the lower echelons of sales management; these are discussed in the following section. In addition, companies using such quantitative performance standards as sales volume quotas and target share-of-the-market percentages require information contained in sales forecasts, which, of course, are prepared not only for sales management’s use but for managerial planning throughout the enterprise.

The methods of obtaining needed information depend upon the sources. Internally generated information, such as that from the data- processing installation, is provided on a routine basis, or in response to requests for special tabulations. Information obtainable only from sales personnel or field sales management personnel is gathered through formal reports; such information is also obtained through personal observation— by trips to the field or through field sales supervisors.

1. System of Field Sales Reports

The fundamental purpose of field sales reports is to provide control information. Good communications require interaction between those preparing and those receiving reports. A good field sales reporting system provides both for communication from the field to headquarters and from the headquarters to the field.

Field sales reports provide sales management with a basis for discussion with sales personnel. They indicate the matters on which salespeople need assistance. The sales executive uses field sales reports to determine whether sales personnel are calling on and selling to the right people, and whether they are making the proper number of calls. Similarly, field sales reports assist in determining how to secure more and larger orders. Field sales reports provide the raw materials that sales management processes to gain insights on giving needed direction to field sales personnel.

A good field-sales reporting system assists sales personnel in their self-improvement programs. Recording accomplishments in written form forces individuals to check their own work. They become their own critics, and self-criticism often is more valuable and more effective than that from headquarters. If this motivates sales personnel to improve coordination of their efforts with sales management’s plans, the managerial process functions more smoothly.

Purposes of field sales reports. It is to important to determine the nature of information field sales report contains and the frequency of its transmittal. The general purpose of all field sales reports is to provide information for measuring performance; many reports, however, provide additional information. Consider the following list of purposes served by field sales reports:

- To provide data for evaluating performance—for example, details concerning accounts and prospects called upon, number of calls made, orders obtained, days worked, miles traveled, selling expenses, displays erected, cooperative advertising arrangements made, training of distributors’ personnel, missionary work, and calls made with distributors’ sales personnel.

- To help the salesperson plan the work—for example, planning itiner aries, sales approaches to use with specific accounts and prospects.

- To record customers’ suggestions and complaints and their reactions to new products, service policies, price changes, advertising campaigns, and so forth.

- To gather information on competitors’ activities—for example, new products, market tests, changes in promotion, and changes in pricing and credit policy.

- To report changes in local business and economic conditions.

- To log important items of territorial information for use in case sales personnel leave the company or are reassigned.

- To keep the mailing list updated for promotional and catalogue materials.

- To provide information requested by marketing research—for example, data on dealers’ sales and inventories of company and competitive products.

Types of sales force reports. Reports from sales personnel fall into six principal groups. [1]

- Progress or call report. Most companies have a progress or call report. It is prepared individually for each call or cumulatively covering all calls made daily or weekly. Progress reports keep the management informed of the salesperson’s activities, provide source data on the company’s relative standing with individual accounts and in different territories, and record information that assists the salesperson on revisits. Usually the call report form records not only calls and sales, but more detailed data, such as the class of customer or prospect, competitive brands handled, the strength and activities of competitors, best time to call, and “future promises.”

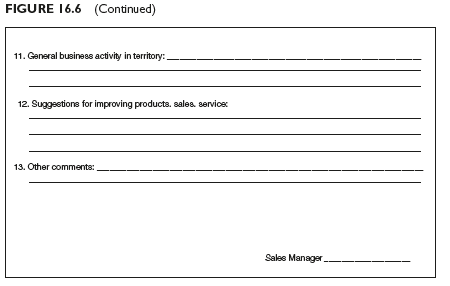

- Expense report. Because most sales personnel are reimbursed for expenses and itemized expense records are required for income tax purposes, most companies have an expense report. From sales management’s standpoint, the purpose is to control the nature and amount of salespersons’ expenses. This report also helps the salesperson exercise self-control over expenses. The expense report reminds salespersons that they are under moral obligation to keep expenses in line with reported sales— some expense report forms require salespersons to “correlate” expenses with sales. The details of the report form vary with the plan for reimbursing expenses. A Weekly Expense Form is shown in Figure 16.3.

- Sales work plan. The salesperson submits a work plan (giving such details as accounts and prospects to be called upon, products and other matters to be discussed, routes to be traveled, and hotels or motels) for a future period, usually a week or a month (see Figure 16.4). The purposes are to assist the salesperson in planning and scheduling activities and to inform management of the salesperson’s whereabouts. The work plan provides a basis for evaluating the salesperson’s ability “to plan the work and to work the plan.”

- New-business or potential new-business report. This report informs management of accounts recently obtained and prospects who may become sources of new business. It provides data for evaluating the extent and effectiveness of development work by sales personnel. A subsidiary purpose is to remind sales personnel that management expects them to get new accounts. Comparing the information secured with data in company files, management evaluates the effectiveness of prospecting (see Figure 16.5).

- Lost-sales report. This report provides information for evaluating a salesperson’s abilities to keep customers and to sell against competition. Lost sales reports point the way to needed sales training, changes in customer service policies, and product improvements. The salesperson reports the reasons for the loss of the business; but receipt of a lost-sales report also causes management to consider further investigation.

- Report of complaint and/or adjustment. This report provides information for analyzing complaints arising from a salesperson’s work, complaints by class of customer, and cost of complaint adjustment. This helps management in detecting needed product improvements and changes in merchandising and service practices and policies. These data also are helpful for decisions on sales training programs, selective selling, and product changes (see Figure 16.5)

Reports from field sales management. In decentralized organizations, field sales executives have an important part in setting sales performance standards. Branch and district sales managers and, in some cases, sales supervisors assist in establishing sales volume quotas for salespeople who, in many companies, also are consulted on their own quotas. Branch and district sales managers, in addition, play roles in breaking down branch and district sales volume quotas to quotas for individual sales personnel, and to products or product lines and/or to types of customers—occasionally, even to specific accounts. At the district level, especially in larger companies, profit and/or expense quotas are sometimes set for individual sales personnel and by product line.

The district sales manager’s planning report is called a district sales plan, often prepared by compiling, with or without revisions, sales work plans, and covering the work or results that each district salesperson expects to accomplish during the month, quarter, or year ahead. Besides breaking down dollar or unit sales volume quotas by products or product lines for each salesperson, district sales plans include standards for number of calls, number of calls on each type of account or on individual accounts, and target number of new dealers and/or distributors. District sales plans usually require the district sales manager to suggest standards for appraising his or her own performance, for example, the recruiting of a certain number of new sales personnel and the carrying out of some amount of sales training. District sales plans are subject to review and to revision by higher sales executives.

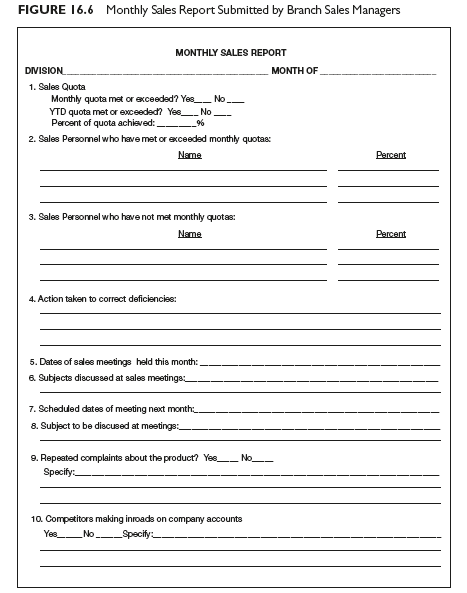

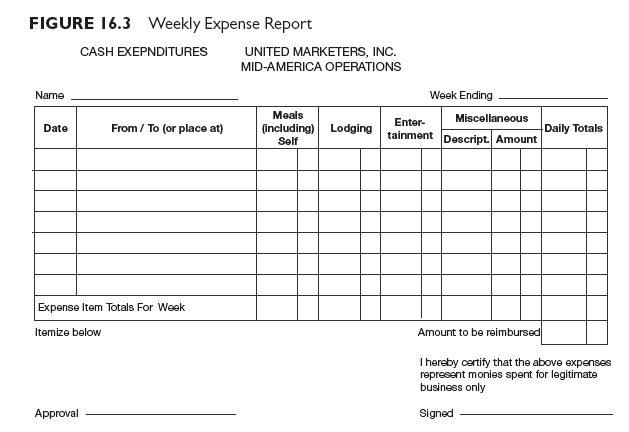

Field sales executives have responsibility for reporting information on personnel performance. Since they are in contact with the sales force most frequently, they are well placed to observe individual sales personnel in the field. Consequently, field sales executives prepare “sales personnel evaluation” reports, often of the merit-rating type, which gather information on qualitative sales performances. In some companies, this is called a “progress report” and includes qualitative information on personnel performance and data comparing individual performance to quantitative standards. See Figure 16.6 for a progress report. Sales personnel evaluation reports are prepared either periodically or each time a district sales manager or supervisor works with a salesperson. As companies increasingly utilize centralized data-processing facilities for processing quantitative data, the role of the district sales office in gathering, collating, and reporting quantitative sales performance data has declined. But no good substitute method for gathering information on qualitative aspects of personnel performances has been found, and the district sales manager continues as the main unit for gathering such information.

The salesperson’s immediate superior (a sales supervisor, branch sales manager, or district sales manager) usually is responsible for appraising his or her performance, but higher sales management reviews these appraisals. Review is necessary (1) to make certain that the appraisal form has been filled out properly, (2) to check against personal bias or errors in judgment, and (3) to rate the rater’s ability to set performance standards and to evaluate sales personnel.

Number of reports. The optimum number of reports is the minimum necessary to produce the desired information. Holding down the number of reports is important since they are generally made out after the selling day. Report preparation places demands on free time, and, unfortunately, the sales people often have the least time. All reports are reviewed from time to time to determine whether the information is worthwhile. When a new report is proposed, the burden of proof of its need is upon its advocates. Information obtainable through other means at no higher cost should not be gathered through field sales reports. Some companies, in assessing the worth of a sales report, discontinue it without notice or insert intentional errors in the form, thus learning whether the report is essential and the use, if any, made of the information.

Design and construction of reports. Each field sales report should be as short as is consistent with its purpose. This is especially important for those submitted by sales personnel—whenever possible, the form should provide for easy checking off of routine informational items. A minimum of clerical work, such as tabulations or comparisons, should be required of sales personnel.

Information on field reports should be so arranged that it can easily be summarized. There should also be set routines for transferring information onto other records. More and more companies have provided sales personnel with laptops equipped with sales force automation and customer relationship management software for submission and analysis of different field activities and reports.

Detail required in sales reports. The amount of detail required in sales reports varies from firm to firm. A company with many sales personnel covering a wide geographical area needs more detailed reports than does a company with a few salespeople covering a limited area. The more freedom that sales personnel have to plan and schedule their activities, the greater should be the detail required in their reports. However, and in apparent contradiction, commission sales personnel are asked for less detail in reports than are salaried salespeople, probably because management feels that it has less power to direct their activities. In general, the higher the caliber of sales personnel, the less is management’s need for details. High-caliber people are expected to exercise self-control, thus reducing the need for detailed formal reporting.

Source: Richard R. Still, Edward W. Cundliff, Normal A. P Govoni, Sandeep Puri (2017), Sales and Distribution Management: Decisions, Strategies, and Cases, Pearson; Sixth edition.

25 May 2021

3 Jan 2018

25 May 2021

24 May 2021

24 May 2021

24 May 2021