1. SALARY STRUCTURES

Most organisations of any size have in place some form of grading structure which is used as the basis for determining the basic rate of pay for each job. Moves towards person-based and performance-related reward in recent years have tended to be used to determine the level of bonus or progression within a grading structure. They have thus been used in addition to and not instead of established job-based systems.

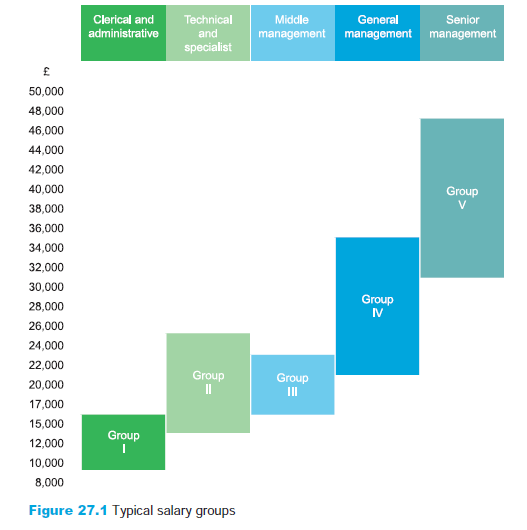

The traditional approach involves developing a salary structure of groups, ladders and steps, whereby different groups or ‘families’ of jobs in an organisation are identified, each having a separate pay scale. Increasingly the term ‘job family’ is being replaced with ‘career framework’ (IDS 2006, p. 2), but the principle is the same. It is illustrated in Figure 27.1.

1.1. Job families

The first element of the structure is the broad groupings of salaries, each group being administered according to the same set of rules. The questions in making decisions about this are to do with the logical grouping of job-holders, according to their common interests, performance criteria, qualifications and, perhaps, bargaining arrangements and trade union membership. Massey (2000, p. 144) suggests the following as a typical seven-way division of jobs into distinct families:

- Executives

- Management

- Professional

- Technical

- Administrative

- Skilled manual

- Manual

The broad salary ranges are then set against each group, to encompass either the maximum and minimum of the various people who will then be in the group or – in the rare circumstance of starting from scratch – the ideal maximum and minimum levels.

As the grouping has been done on the basis of job similarity, the attaching of maximum and minimum salaries can show up peculiarities, with one or two jobs far below a logical minimum and others above a logical maximum. This requires the limits for the group to be put at the ‘proper’ level, with the exceptions either being identified as exceptions and the incumbents being paid a protected rate or being moved into a more appropriate group.

Salary groups will not stack neatly one on top of another in a salary hierarchy. There will be considerable overlap, recognising that there is an element of salary growth as a result of experience as well as status and responsibility. No overlap at all (a rare arrangement) emphasises the hierarchy, encouraging employees to put their feet on the salary ladder and climb, but the clarity of internal relativities may increase the dissatisfaction of those on the lower rungs and put pressure on the pay system to accommodate the occasional anomaly, especially if climbing is not well supported. Overlapping grades blur the edges of relativities and can reduce dissatisfaction at the bottom, but introduce dissatisfaction higher up.

Another reason why pay scales for different job families usually overlap is to accommodate scales of different length. A family with a flat hierarchy will tend to have a small number of scales with many steps, while the steep hierarchy will tend to have more scales, but each with fewer steps. One of the main drawbacks of overlapping scales is the problem of migration, where an employee regards the job as technical at one time and makes a case for it to be reclassified as administrative at another time, because there is no further scope for progress in the first classification. Another aspect of migration is the more substantive case of employees seeking transfer to other jobs as a result of changes in the relative pay scales, which reduce rigidity in the internal labour market.

1.2. Ladders and steps

Because employees are assumed to be career oriented, salary arrangements are based on that assumption, so each salary group has several ladders within it and each ladder has a number of steps (often referred to as ‘scales’ and ‘points’). In the traditional model increments are awarded annually, reflecting individual seniority. Hence the new starter normally enters employment with the organisation at the lowest rung of the ladder in the grade for the job. At the end of each completed year of service individuals are then awarded an increment until after six or seven years they reach the top of the ladder – the ceiling for the relevant grade. At this point pay progression stops, except for any annual cost of living rise. The only way in which an individual can gain a higher income within the organisation is to secure promotion to a more highly graded job. This involves moving up on to a new ladder, at which point annual incremental pay awards commence again. Such approaches are still common in the public sector, although, as in many private sector organisations, incremental progress is increasingly linked to satisfactory performance, skills acquisition or the achievement of agreed objectives.

The number of ladders will vary from organisation to organisation depending on particular circumstances, but for many large organisations offering a potential longterm career path it would be usual for there to be five or six separate ladders or grades for each job family. IDS (2006, p. 30) give the following example of the approach used at Zarlink Semiconductors. Here there are six ladders for each job family, descriptors being used to indicate broadly which jobs are graded at which level:

- entry

- developing

- working

- senior (team leader)

- specialist (manager)

- principal (director)

As with groups there is considerable overlap, the top rung of one ladder being rather higher than the bottom rung of the next. Taking a typical general employee group as an example, we could envisage four ladders, as shown in Figure 27.2. The size of the differential between steps varies from £200 to £600 according to the level of the salary, and the overlapping could be used in a number of ways according to the differing requirements. Steps 6 and 7 on each ladder would probably be only for those who had reached their particular ceiling and were unlikely to be promoted further, while steps 4 and 5 could be for those who are on their way up and have made sufficient progress up one ladder to contemplate seeking a position with a salary taken from the next higher ladder.

The figures attached to the ladders in this example are round, in the belief that salaries are most meaningful to recipients when they are in round figures. However, ladders are sometimes developed with steps having a more precise arithmetical relationship to their relative position, so that each step represents the same percentage increase. Equally, some ladders have the same cash amount attached to each step. Some commentators place importance on the relationship of the maximum to the minimum of a ladder, described as the span, and the relationship between the bottom rung of adjacent ladders, referred to as the differential. A span of 50 per cent above the minimum or 20 per cent on either side of the midpoint is common.

1.3. The self-financing increment principle

It is generally believed that fixed incremental payment schemes are self-regulating, so that introducing incremental payment schemes does not mean that within a few years everyone is at the maximum. The assumption is that just as some move up, others retire or resign and are replaced by new recruits at the bottom of the ladder. However, this will clearly not be the case when staff turnover is low, nor will it be the case in very tight labour markets where it is necessary to appoint external candidates to points on the scales which reflect their market worth rather than simply starting them at the base of the grade as would typically occur in the case of an internal promotion.

1.4. Why not one big (happy) family?

An important question is whether there should be subgroupings within the organisation at all, or whether all employees should be paid in accordance with one overall salary structure. Internal relativities disappear; there is only a differential structure. This arrangement has many attractions, as it emphasises the integration of all employees and may encourage them to identify with the organisation as a whole, it is administratively simple and can stimulate competition for personal advancement. It also allows more flexibility in the pay that is arranged for any individual and removes the problem that tends to occur with a family approach whereby some necessary but peripheral jobs do not readily fit into any of the major families of jobs in the organisation.

Interest in the development of single pay structures has increased in recent years for a number of reasons. It has accompanied a more general preference among employers for taking an organisation-wide approach to a whole range of HR initiatives. New technologies often demand a more flexible workforce, leading to a blurring of the organisational distinction between groups of workers. Harmonisation of the terms and conditions of employment follows, so that all employees work the same number of hours, are given the same training opportunities and enjoy the same entitlement to occupational pensions, sick pay and annual leave. Such practices have also been conspicuously imported into British subsidiaries of Japanese and American companies, which typically have longer experience of single-status employment practices. Moreover, substantial increases in the occurrence and frequency of corporate mergers and acquisitions means that payment systems can become overwhelmingly complex when previously separate organisations are brought together for the first time. The result is a tendency to simplify as a means of achieving a workable harmonised salary system.

Interest has also arisen following recent judgments in which courts have awarded equal pay to employees who have sought to compare their jobs with those of other individuals in wholly different job families. As a result, employers who continue to operate different mechanisms for determining the pay of different groups of employees have had difficulty in defending their practices when faced with equal value claims.

The argument against such a system is that it applies a common set of assumptions that may be inappropriate for certain groups. In general management, for instance, it will probably be an assumption that all members of the group will be interested in promotion and job change; this will be encouraged by the salary arrangements, which will encourage job-holders to look for opportunities to move around. In contrast, the research chemist will be expected to stick at one type of job for a longer period, and movement into other fields of the company’s affairs, such as personnel or marketing, will often be discouraged. For this reason it will be more appropriate for the research chemist to be in a salary group with a relatively small number of ladders, each having a large number of steps; while a general management colleague will be more logically set in a context of more ladders, each with fewer steps.

There are other reasons too for sticking with or moving towards a structure composed of a number of different distinct job families. Key is the flexibility it gives employers to respond efficiently to developments in specific labour markets. As a result, when one group of staff become harder to recruit and retain because demand for their skills increases, pay rates can be adjusted upwards without the need to incur the costs associated with a general pay rise for all employees.

Moreover, in practice it is very difficult to develop a single pay structure which is acceptable to all parties in an organisation. The more diverse the skills, values or union affiliation of the employees, the more difficult is such a single job family. The factors used to compare job with job always tend to favour one grouping at the expense of another; one job at the expense of another. The wider the diversity of jobs that are brought within the purview of a single scheme, the wider will be the potential dissatisfaction, with the result that the payment arrangement is one that at best is tolerated because it is the least offensive rather than being accepted as satisfactory.

2. BROADBANDING

Attention has increasingly been given in recent years to the introduction of ‘broadbanding’ as a way of retaining the positive features of traditional pay scales while reducing some of the less desirable effects (see Armstrong and Brown 2001; CIPD 2007). One of these less desirable effects is the built-in incentive to focus on being promoted rather than on performing well in the current job. This can lead to individuals playing damaging political games in a bid to weaken the position of colleagues or even undermine their own supervisors. Inflexibility can also occur when individuals refuse to undertake duties or types of work associated with higher grades. Moreover, in making internal equity the main determinant of pay rates within an organisation, rigid salary structures prevent managers from offering higher salaries to new employees. This tends to hinder effective competition in some labour markets.

Broadbanding essentially involves retaining some form of grading system while greatly reducing the numbers of grades or salary bands. The process typically results in the replacement of a structure consisting of ten or a dozen distinct grades with one consisting of only three or four. Pay variation within grades is then based on individual performance, skill or external market value rather than on the nature and size of the job. The great advantage of such approaches is their ability to reduce hierarchical thinking. Differences in pay levels still exist between colleagues but they are no longer seen as being due solely to the fact that one employee is graded more highly than another. This can reduce feelings of inequity provided the new criteria are reasonably open and objective. As a result, teamwork is encouraged as is a focus on improving individual performance in order to secure higher pay.

In theory, therefore, broadbanded structures increase the extent to which managers have discretion over the setting of internal differentials, introduce more flexibility and permit organisations to reward performance or skills acquisition as well as job size. Their attraction is that they achieve this while retaining a skeleton grading system which gives order to the structure and helps justify differentials. Time will tell how acceptable such approaches are to the courts when it comes to judging equal value claims (see the section below, ‘The legal framework for pay and reward’, under ‘Equal Value’).

Source: Torrington Derek, Hall Laura, Taylor Stephen (2008), Human Resource Management, Ft Pr; 7th edition.

I¦ve recently started a website, the information you provide on this website has helped me greatly. Thanks for all of your time & work.