While employers have been paying employees with money for centuries, it is only quite recently that organisations in the UK and in many other countries have begun to develop identifiable ‘reward strategies’ which seek to help achieve defined organisational objectives and priorities. The reason, as was explained in Chapter 20, is that until the 1980s in the private sector, and much more recently in the public sector, the prevalent industrial relations system tended to restrict the freedom of manoeuvre that managers had to design and develop payment packages that helped them to meet their objectives. Collective bargaining with trade unions was the method used to determine the pay and conditions that most people received, much of it carried out at a national or industry level. Managers in many organisations were thus restricted to deciding who should be employed on which grade, how they should progress up the grade hierarchy, what should be paid by way of an annual increment and how much overtime they worked. This system of multi-employer bargaining declined steeply during the 1980s and 1990s, so that by 2004 only 36 per cent of public sector employees and just one per cent of those employed in the private sector had their pay determined by such arrangements (Kersley et al. 2006, p. 184). The breaking down of this long-established system has enabled organisations to innovate by introducing payment systems which reward individual skills, effort and performance to a far greater degree. Much greater flexibility has been achieved in the provision of benefits, while rigid grade hierarchies have tended to be replaced by approaches which give managers much more say in how much an individual job is worth and how annual pay rises should be determined. The result has been a great deal of experimentation, some examples of which have proved more successful than others, and much more variety of practice across industries.

Over the last twenty years reward management has also attracted the keen interest of consultants and academic researchers leading to the publication of hundreds of books and thousands of articles about the effectiveness of different systems and approaches. We thus have a good deal of robust research evidence available on which to base practice in organisations. There remains, however, according to Armstrong et al. (2005, p. 4) a worrying ‘knowing-doing gap’ resulting in the promulgation of reward practices in organisations which are known by students of reward to be highly problematic and a failure on the part of managers to adopt approaches which the research shows are a great deal more effective. Moreover, to a great degree we are still at the experimentation stage with some approaches, and this means that fierce debates rage among commentators about the effectiveness, efficiency and fairness of systems which aim to enhance individual effort, encourage skills acquisition, reward specific employee behaviours and try to establish an identity of interest between employers and their staff.

1. TOTAL REWARD

A variety of different terms are used to describe the rewards that are given by an employer in return for the work carried out by workers. In previous editions of this book we have used the term ‘payment’, but this is often nowadays seen as being too narrow in scope because many of the rewards that people take from their work do not take a monetary form. ‘Compensation’ is a term widely used in the American literature, yet the idea of compensation is that it involves making amends for something that has caused loss or injury. Do we want to suggest that work necessarily causes loss or injury?

‘Remuneration’ is a more straightforward word which means exactly the same as payment but has five more letters and is misspelled (as renumeration) more often than most words in the human resource manager’s lexicon. ‘Reward’ is not a perfect term to use because it suggests a special payment for a special act, but it is the best available for describing the whole range of elements which combine to make work ‘rewarding’ and worthwhile rather than ‘unrewarding’ and thankless.

For the most part we will be focusing in this Part of the book on transactional or tangible rewards, by which we mean those which are financial in nature. But it is important to remember that employees also value the intangible (or relational) rewards which they gain from coming to work, to all of which we have made extensive reference in earlier chapters. These include opportunities to develop both in terms of career and more generally as a human being, the social life which is associated with working in communal settings, recognition from managers and colleagues for a job well done and for the effort expended, and more generally from a sense of personal achievement. Increasingly the opportunity to work flexibly so as to achieve a better ‘work-life balance’ is discussed in this context too (see Chapter 31). The trend towards viewing reward policies and practices as extending well beyond the realms of payment has led to widespread interest in the concept of ‘total reward’ which involves managers viewing the way that they reward employees in the round, taking equal account of both the tangible and intangible ingredients that together help to make work and jobs ‘rewarding’ in the widest sense of the word. The idea is effectively illustrated in graphical form by Armstrong and Brown (2006, p. 25) in their model adapted from work by the Towers Perrin reward consultancy (see Figure 26.1). Here four distinct categories of rewards are identified, the implication being that each has equal potential significance as a source of reward from the employee perspective.

The change in perspective away from a narrow focus on payment towards a broader focus on ‘total reward’ has come about largely because of developments in the commercial environment. Year on year, organisations operating in the private sector are facing greater competitive pressure in their product markets leading them to search for ways of reducing their costs while retaining or improving the levels of quality they achieve. In the public sector competitive forces increasingly play a role too, but here pressures to keep costs down come primarily from taxpayers seeking good value for their money. The trouble is that these pressures are being faced simultaneously with tighter labour market conditions, making it difficult for employers to recruit, retain and motivate the staff they need without substantially increasing pay levels. Organisations are embracing a variety of responses to this conundrum. One involves employing fewer, but more highly paid people to carry out existing work more efficiently. Another involves keeping a lid on payment levels while simultaneously looking for other ways of rewarding staff effectively. It is this latter approach which has led managers to think about the ‘total reward’ package that they offer.

As a rule managing the tangible, financial components is relatively unproblematic provided basic principles are adhered to and the correct technical decisions are made. While they enable organisations to secure a degree of competitive advantage in their labour markets, these tangible parts of a total reward package are readily imitated by competitors. It is much harder, in practice, to replicate intangible rewards. Over the longer term it is thus in the interests of organisations to improve the perceived value of the intangible elements, but that is a great deal harder both to achieve and to evaluate. Moreover, several important intangible rewards are ‘intrinsically’ rather than ‘extrinsically’ motivating, and by definition cannot be directly provided by managers. These are terms used by psychologists to distinguish between sources of positive motivation which are external to individuals and given to them by their employer, such as money or praise, and those which are internally generated. An example of intrinsic motivation is someone putting a great deal of effort into a project at work simply because he or she finds it interesting or enjoyable. The result may be very considerable satisfaction on the part of the employee concerned, but this has not resulted directly from any management action. All managers can do is try to create and sustain a culture in which individual employees can achieve intrinsic motivation and hence experience work which is rewarding.

2. REWARD STRATEGIES

A major current feature of the literature and rhetoric about remuneration systems has been a concern with defining and refining reward strategies. While different writers have different ideas about what exactly constitutes a strategic approach to the management of reward, most agree that it is primarily about aligning an organisation’s payment arrangements and wider reward systems with its business objectives. This means developing systems which enhance the chances that an organisation’s employees will seek actively to contribute to the achievement of its goals. So if improved quality of service is the major business objective, this should be reflected in a payment system which rewards front-line staff who provide the best standards of service to customers. Alternatively, if increased productivity is sought, then an approach which rewards efficiency would be more appropriate. But choices in this area are not always as straightforward as this because organisations are obliged to compete with one another for good staff as well as for customers. And as Charles Cotton points out in the most recent CIPD survey of reward practices, ‘respondents report that employees are becoming just as discerning as their customers in what they want from their employer’ (CIPD 2007, p. 33). The tighter the labour market becomes, the harder it is to recruit and retain the best-qualified people, and the more pressure there is placed on employers to develop rewards packages that suit employees as much as they suit their own needs.

The extent to which organisations have taken full advantage of the opportunity to develop identifiable reward strategies since the disintegration of national-level, multiemployer bargaining has long been an area of contention. Moves in this direction by some prominent employers and the growth of specialist reward consultancies specialising in work of this kind has led some analysts to hail the dawn of a new era in reward management practice. Armstrong and Murlis (1998, pp. 12-14), for example, go so far as to argue that present-day practice is characterised by an acceptance of a ‘new pay philosophy’ in which decisions about payment levels and packages ‘flow from the overall strategy’ of the organisation. According to their view reward policy now increasingly underpins employer objectives and promotes change by rewarding ‘results and behaviour consistent with the key goals of the organisation’. By contrast, academic researchers have tended to take issue with this assessment, often quite stridently. While they agree that major developments have occurred in pay determination over recent decades, they dispute the claims made about the extent of change and question how far organisations are taking a long-term strategic approach to the management of pay. Smith (1993) and Thompson (1998), in particular, have argued that managers are just as short-termist and reactive when making decisions about pay as they always were. Changes are introduced for damage limitation reasons, to respond to immediate recruitment difficulties or in response to government initiatives rather than as a means of aligning practices with organisational goals. Kessler (2001) and Poole and Jenkins (1998) also report considerable gaps in many organisations between the rhetoric and reality of strategic activity in pay management. Despite some examples of the development of genuinely original approaches in some larger private sector organisations, there is little evidence generally of the adoption of strategic principles as far as reward is concerned across most UK organisations. More recent surveys of reward practice back up this assessment, only 35 per cent of respondents to the CIPD’s 2007 survey claiming to have a reward strategy (CIPD 2007, p. 6). The percentage was higher in the latest IRS survey (at 45 per cent), but only 18 per cent of their respondents had an identifiable written reward strategy, leading the authors to conclude that there is ‘more talk of reward strategies, but little action’ (IRS 2006, p. 28).

So what does a written reward strategy look like? According to Armstrong and Brown (2006, p. 34) there are four key components. First of all there needs to be a ‘statement of intentions’ setting out, in general terms, what the reward strategy of the organisation is seeking to achieve and which reward initiatives have been chosen in order to achieve these core objectives. Second, these ideas are expanded through a more detailed ‘rationale’ which explains the objectives in greater depth and shows how the various elements of the organisation’s reward policy support the achievement of those objectives. In effect this amounts to a statement of the business case that underpins the strategy. To that end the rationale should include costings, a statement of the benefits that will accrue and an indication of the means that will be used to evaluate its success. The third element is an explanation of the guiding principles or values that have been used in developing the initiatives and that will be used to adapt them in the future. Typically this will include statements which deal with ethical issues or which reiterate a commitment to core principles such as equality between men and women, fair dealing or rewarding exceptional individual performance. The final component is an implementation plan, setting out exactly what initiatives are being brought forward and when, who has responsibility for their introduction and what their cost will be.

Later in this chapter and in those which follow we will be exploring the major alternative initiatives available to employers when developing their reward strategies. However, before we can get to this stage we first need to consider the major objectives that employers and employees have as far as their reward package is concerned. While meeting each of these effectively is a prerequisite for the long-term success of any reward strategy, the significance of different objectives varies over time because of changing environmental conditions and also varies between organisations. There are also several different alternative means available of meeting each objective.

Employer objectives

Reward strategies and the initiatives developed as part of those strategies should be judged according to their ability to meet certain core objectives.

Attracting staff

The reward package on offer must be sufficiently attractive vis-a-vis that of an organisation’s labour market competitors to ensure that it is able to secure the services of the staff it needs. The more attractive the package, the more applications will be received from potential employees and the more choice the organisation will have when filling its vacancies. Attractive packages thus allow the appointment of high-calibre people and often mean that organisations are able to fill vacancies more quickly than is the case with a reward offering which is either unattractive or poorly communicated. However, what is ‘attractive’ in total reward terms in one labour market will be less attractive in others because people vary in what they are looking for. There is thus a need to establish what the target market values most and to tailor the offering accordingly.

Retaining staff

The costs associated with recruiting and developing people, as well as the growing significance of specialist organisational knowledge in creating value and maintaining competitive advantage, mean that retaining effective performers is a central aim of reward strategy in many organisations, particularly those competing in knowledgeintensive industries where highly qualified people are in short supply. This requires a

package which is attractive enough to prevent people from becoming dissatisfied and looking elsewhere for career development opportunities. It may also involve the development of policies which reward seniority so as to provide an incentive for staff to stay when they might otherwise consider applying for alternative work.

Motivating staff

Aside from helping to ensure that effective performers are recruited and retained, in more general terms it is necessary that the reward package they are given serves to motivate positively and does not demotivate. The question of the extent to which money ever can positively motivate has long been debated by occupational psychologists, many of whom accept that the power of monetary reward to motivate is very limited, at least over the longer term. What is not in doubt, however, is the very considerable power of poorly designed or implemented reward practices to demotivate, particularly when they are perceived by staff to be inequitable in some shape or form. Ultimately the aim must be to reward people in such a way as to create the conditions in which they are prepared to work hard to help achieve their employer’s objectives and, if possible, to demonstrate discretionary effort. Employers who want their workforces to be positively engaged with their work, to participate in continuous improvement programmes and to work beyond contract when required must have in place a reward package which does not demotivate and which, as far as is possible, motivates positively. In this regard, the total reward concept referred to above has plenty to offer as it incorporates intrinsic motivators alongside extrinsic motivators.

Driving change

Pay can be used specifically as one of a range of tools underpinning change management processes. The approach used is to tie higher base pay, bonuses or promotion to the development of new behaviours, attitudes or skills gained by employees. Pay works far more effectively than simple exhortation because it provides a material incentive to those whose natural inclination is to resist change. It also sends out a powerful message to employees indicating the seriousness of the employer’s intentions as regards proposed or ongoing changes. The use of pay in this way is sometimes criticised because it serves to enhance management control in a very conspicuous way. Sociologists in particular tend to be uneasy about the capacity of payment systems to reinforce the position of powerful groups in organisations and in society generally at the expense of those who are relatively powerless. Examples are the use by employers of individualised reward packages which undermine the power of trade unions to organise and resist effectively and systems which have the effect of increasing the pay of predominantly male groups vis-a-vis those which are predominantly female.

Corporate reputation

Aside from the aim of developing and maintaining a reputation as a good employer in the labour market, organisations are increasingly concerned to establish a positive corporate reputation more generally. For some the notion of ‘prestige’ is something they aim for as part of a business strategy that seeks to produce high-quality, high-value added or innovative goods or services. For others the maintenance of an ethical reputation is

important in order to attract and retain a strong customer base. Either way delivery is significantly linked in part to the organisation’s reputation as an employer. Paying poorly or having in place policies which are perceived as operating unfairly serves to undermine any reputation gained for being either a prestigious organisation or one which acts ethically and in a socially responsible manner.

Affordability

The above objectives are all desirable for organisations and form the basis of their reward strategies. But in this field of HR activity there is a major restriction in the shape of affordability which serves to limit what can be done at any time. The extent to which a particular objective is affordable also varies over time and tends to be unpredictable as so much depends on the current financial performance of the organisation. If money were no object organisations would develop ‘ideal’ reward packages which paid above market rates to ensure that the best people were recruited and retained and which linked pay both to individual and collective achievement so as to maximise effort and performance. But the real world is not like this except, some would argue, when it comes to developing pay packages for senior executives, so tough choices inevitably have to be made when devising reward strategies. Organisational objectives have to be prioritised and decisions made about how limited resources are best to be deployed so as to maximise the positive impact of reward management interventions on the organisation’s performance.

Employee objectives

You might think that employees have only one objective as far as reward is concerned, namely to maximise the amount that they earn. Indeed some theorists further argue that employees are primarily interested in maximising the amount they earn while also minimising the effort they put in to achieve these earnings. This was one of the assumptions about worker behaviour that underlay scientific management thinking in the early twentieth century (see Steers et al. 1996, pp. 25-28). In fact for most employees aims are more diverse and more subtle, particularly when the full range of elements that make up a total reward package are taken into consideration.

Purchasing power

The absolute level of weekly or monthly earnings determines the standard of living of the recipient, and will therefore be the most important consideration for most employees. How much can I buy? Employees are rarely satisfied about their purchasing power, and the annual pay adjustment will do little more than reduce dissatisfaction, even if it exceeds the current level of inflation. Enhanced satisfaction only occurs when a pay rise is given which surpasses expectations. It is important to remember, however, that surveys of employee satisfaction invariably show that while a good majority of employees are dissatisfied with the level of their pay, most are satisfied or very satisfied with other aspects of their jobs (see Kersley et al. 2005, p. 33).

Fairness

Elliott Jacques (1962) averred that every employee had a strong feeling about the level of payment that was fair for the job. In most cases this is a rough, personalised

evaluation of what is appropriate, bearing in mind the going market rate and personal contribution vis-a-vis that of fellow employees. The employee who feels underpaid is likely to demonstrate the conventional symptoms of withdrawal from the job: looking for another, carelessness, disgruntlement, lateness, absence and the like. Perhaps the worst manifestation of this is among those who feel the unfairness but who cannot take a clean step of moving elsewhere. They then not only feel dissatisfied with their pay level, but also feel another unfairness too: being trapped in a situation they resent. Those who feel they are overpaid (as some do) may simply feel guilty, or may seek to justify their existence in some way by trying to look busy. That is not necessarily productive.

Rights

A different aspect of relative income is that concerned with the rights of the employee to a particular share of the company’s profits or the nation’s wealth. The employee is here thinking about whether the division of earnings is providing fair shares of the Gross National Product. The focus is often on the notion of need – the idea that people have a right to a greater share because they or their families are suffering unjustly. These are features of many trade union arguments and part of the general preoccupation with the rights of the individual.

Recognition

Most people have an objective for their payment arrangements, that their personal contribution is recognised. This is partly seeking reassurance, but is also a way in which people can mould their behaviour and their career thinking to produce progress and satisfaction. It is doubtful if financial recognition has a significant and sustained impact on performance, but providing a range of other forms of recognition while the pay packet is transmitting a different message is certainly counterproductive.

Composition

How is the pay package made up? The growing complexity and sophistication of payment arrangements raises all sorts of questions about pay composition. Is £400 pay for 60 hours’ work better than £280 for 40 hours’ work? The arithmetical answer that the rate per hour for the 40-hour arrangement is marginally better than that for 60 hours is only part of the answer. The other aspects will relate to the individuals, their circumstances and the conventions of their working group and reference groups. Another question about composition might be: is £250 per week plus a pension better than £270 per week without? Such questions do not produce universally applicable answers because different groups of employees tend to have different priorities. For example, younger staff tend to be more interested in maximising cash earnings than older colleagues who tend to be more interested in indirect forms of payment such as pension arrangements. Those in mid-career who have mortgages to pay off are likely to be interested in overtime rates and in systems which allow them to trade holiday entitlement or other benefits for cash. For second-income earners in a family cash is often less significant than flexible working arrangements, childcare vouchers or creche facilities.

3. SETTING BASE PAY

One of the most important decisions in the development of reward strategies concerns the mechanism or mechanisms that will be used to determine the basic rate of pay for different jobs in the organisation. There are, of course, restrictions on management action in this area provided by the law. Since 1999 the UK has had a National Minimum Wage (£5.35 an hour in 2007) to which workers over the age of 22 are entitled; a lower minimum rate is set for those aged 18-22. Equal pay law is a further way in which the state intervenes, providing a mechanism for employees to complain when they consider their pay to be unjustifiably lower than that paid to a colleague of the opposite sex. Moreover, in many countries incomes policies are operated as tools of inflation control. These restrict the amount of additional pay that people can receive in any one year while remaining in the same job. While formal incomes policies were abandoned in the UK after the 1970s, similar thinking continues to underpin government decision making in the area of public sector pay (Thorpe 2000, pp. 34-5).

A further restriction on management action is the nature of the product markets in which their organisations operate. The extent of this influence varies according to how important labour costs are in deciding product cost, and how important product cost is to the customer. In a labour-intensive and low-technology industry such as catering, there will usually be such pressure on labour costs that the pay administrator has little freedom to manipulate pay relationships. In an area such as magazine printing, the need of the publisher to get the product out on time is so great that labour costs, however high, may be of relatively little concern. In this situation the pay negotiators have much more freedom of manoeuvre.

It is possible, notwithstanding the above restrictions, to identify four principal mechanisms for the determination of base pay. They are not entirely incompatible, although one tends to be used as the main approach in most organisations.

3.1. External market comparisons

In making external market comparisons the focus is on the need to recruit and retain staff, a rate being set which is broadly equivalent to ‘the going rate’ for the job in question. The focus is thus on external relativities. Research suggests that this is always a major contributing factor when organisations set pay rates, but that it increases in significance higher up the income scale. Some employers consciously pay over the market rate in order to secure the services of the most talented employees. Others ‘follow the market’, by paying below the going rate while using other mechanisms such as flexibility, job security or longer-term incentives to ensure effective recruitment and retention. In either case the decision is based on an assessment of what rate needs to be paid to compete for staff in different types of labour market. Going rates are more significant for some than for others. Accountants and craftworkers, for instance, tend to identify with an external employee grouping. Their assessment of pay levels is thus greatly influenced by the going rate in the trade or the district. A similar situation exists with jobs that are clearly understood and where skills are readily transferable, particularly if the employee is to work with a standard piece of equipment. Driving heavy goods vehicles is an obvious example, as the vehicles are common from one employer to another, the roads are the same, and only the loads vary. Other examples are secretaries, switchboard operators and computer operators. Jobs that are less sensitive to the labour market are those that are organisationally specific, such as much semi-skilled work in manufacturing, general clerical work and nearly all middle-management positions.

There are several possible sources of intelligence about market rates for different job types at any one time. A great deal of information can be found in published journals such as the pay bulletins issued by Incomes Data Services (IDS) and Industrial Relations Services (IRS), focusing on the hard-to-recruit groups such as computer staff. More detailed information can be gained by joining one of the major salary survey projects operated by firms of consultants or by paying for access to their datasets. Information on specific types of job, including international packages for expatriate workers, is collected by specialised consultants and can be obtained on payment of the appropriate fee. White (2000, pp. 44-5) identifies a range of other sources of UK pay data including the Confederation of British Industry’s Pay Databank and the Office of Manpower Economics. In addition there are more informal approaches such as looking at pay rates included in recruitment advertisements in papers, at job centres and on web-based job- board sites. New staff, notably HR people, often bring with them a knowledge of pay rates for types of job in competitor organisations and can be a useful source of information. Finally, it is possible to join or set up salary clubs. These consist of groups of employers, often based in the same locality, who agree to share salary information for mutual benefit.

3.2. Internal labour market mechanisms

Just as there is a labour market of which the company is a part, so there is a labour market within the organisation which also needs to be managed so as to ensure effective performance. According to Doeringer and Piore (1970) there are two kinds of internal labour market: the enterprise and the craft. The enterprise market is so called because the individual enterprise defines the boundaries of the market itself. Such will be the market encompassing manual workers engaged in production processes, for whom the predominant pattern of employment is one in which jobs are formally or informally ranked, with the jobs accorded the highest pay or prestige usually being filled by promotion from within and those at the bottom of the hierarchy usually being filled only from outside the enterprise. It is, therefore, those at the bottom that are most sensitive to the external labour market. Doeringer and Piore point out that there is a close parallel with managerial jobs, the main ports of entry being from management trainees or supervisors, and the number of appointments from outside gradually reducing as jobs become more senior. This modus operandi is one of the main causes of the problems that redundant executives face.

Recent American research has stressed the importance of this kind of internal labour market in determining pay rates. Here the focus is on internal differentials rather than external relativities. An interesting metaphor used is that of the sports tournament in which an organisation’s pay structure is likened to the prize distribution in a knock-out competition such as is found, for example, at the Wimbledon Tennis Championships. Here the prize money is highest for the winner, somewhat lower for the runner-up, lower again for the semi-final losers and so on down the rounds. The aim, from the point of view of the tournament organisers, is to attract the best players to compete in the first round, then subsequently to give players in later rounds an incentive to play at their peak. According to Lazear (1995, pp. 26-33), the level of base pay for each level in an organisation’s hierarchy should be set according to similar principles. The level of pay for any particular job is thus set at a level which maximises performance lower down the hierarchy among employees competing for promotion. The actual performance of the individual receiving the pay is less important.

The second type of internal labour market identified by Doeringer and Piore is the craft market, where barriers to entry are relatively high – typically involving the attainment of a formal qualification. However, once workers are established in the market, seniority and hierarchy become unimportant as jobs and duties are shared among the individuals concerned. Such arrangements are usually determined by custom and practice, but are difficult to break down because of the vested interests of those who have successfully completed their period of apprenticeship. Certain pay rates are expected by those who have achieved the required qualification and it is accepted by everyone that this is a fair basis for rewarding people.

3.3. Job evaluation

We assess job evaluation in some detail in the next chapter. Here it is necessary only to define the term and identify it as one of the four principal mechanisms of pay determination. Job evaluation involves the establishment of a system which is used to measure the size and significance of all jobs in an organisation. It results in each job being scored with a number of points, establishing in effect a hierarchy of all the jobs in the organisation ranging from those which require the most knowledge and experience and which carry a great deal of responsibility (i.e. senior management and specialist professional jobs) to those which require least knowledge and experience and require the job-holder to carry relatively low levels of responsibility. Each job is then assimilated to an appropriate grade and payment is distributed accordingly.

The focus is thus on the relative worth of jobs within an organisation and on comparisons between these rather than on external relativities and comparisons with rates being paid by other employers. Fairness and objectivity are the core principles, an organisation’s wage budget being divided among employees on the basis of an assessment of the nature and size of the job each is employed to carry out. Usage of job evaluation has increased in recent years. It is currently used by just over half of public sector organisations in the UK and by 15 per cent of companies operating in the private sector (CIPD 2007, p. 10).

3.4. Collective bargaining

The fourth approach involves determining pay rates through collective negotiations with trade unions or other employee representatives. Thirty years ago this was the dominant method used for determining pay in the UK, negotiations commonly occurring at industry level. The going rates for each job group were thus set nationally and were adhered to by all companies operating in the sector concerned. Recent decades have seen a steady erosion of these arrangements, collective bargaining being decentralised to company or plant level in the manufacturing sector, where it survives at all. Meanwhile the rise of service sector organisations with lower union membership levels has ensured that collective bargaining arrangements now cover only a minority of UK workers. According to Kersley et al. (2006, p. 180) only 40 per cent now have any of their terms and conditions determined in this way, collective bargaining over any kind of issue continuing in only 27 per cent of workplaces. The experience of many other countries is similar, but there remain regions such as Eastern Europe and Scandinavia where collective bargaining remains the major determinant of pay rates. Where separate clusters of employees within the same organisation are placed in different bargaining groups and represented by different unions, internal relativities become an issue for resolution during bargaining.

In carrying out negotiations the staff and management sides make reference to external labour market rates, established internal pay determination mechanisms and the size of jobs. However, a host of other factors come into the equation too as each side deploys its best arguments. Union representatives, for example, make reference to employee need when house prices are rising and affordable accommodation is hard to find. Both sides refer to the balance sheet, employers arguing that profit margins are too tight to afford substantial rises, while union counterparts seek to gain a share of any increased profits for employees. However good the case made, what makes collective bargaining different from the other approaches is the presence of industrial muscle. Strong unions which have the support of the majority of employees, as is the case in many public sector organisations, are able to ensure that their case is heard and taken into account. They can thus ‘secure’ a better pay deal for their members than market rates would allow.

4. THE ELEMENTS OF PAYMENT

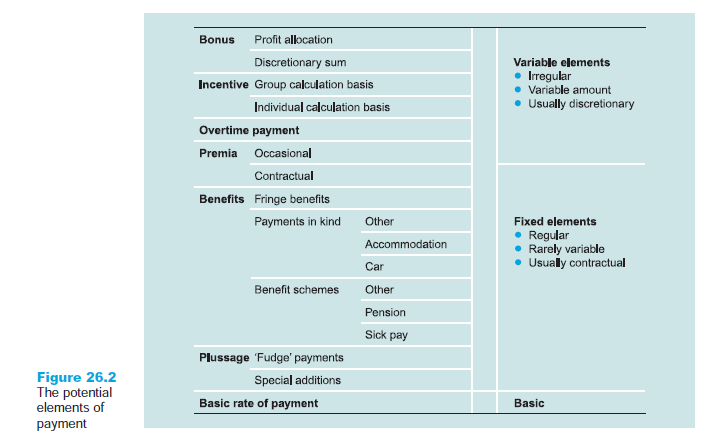

Once the mechanisms for determining rates of pay for jobs in an organisation have been settled, the second key strategic decision relates to the make-up of the pay package. Here there is a great deal of potential choice available. What is included and to what extent are matters which should be decided with a view to supporting the organisation’s objectives and encouraging the necessary attitudes and actions on the part of employees. The payment of an individual will be made up of one or more elements from those shown in Figure 26.2. Fixed elements are those that make up the regular weekly or monthly payment to the individual, and which do not vary other than in exceptional circumstances. Variable elements can be varied by either the employee or the employer.

4.1. Basic rate

The irreducible minimum rate of pay is the basic. In most cases this is the standard rate also, not having any additions made to it. In other cases it is a basis on which earnings are built by the addition of one or more of the other elements in payment. Some groups of employees, such as operatives in the footwear industry, have little more than half of their earnings in basic, while primary and secondary schoolteachers have virtually all their pay in this form. In the UK as many as 60 per cent of employees receive no additional payments at all beyond their basic pay (Grabham 2003, p. 398).

4.2. Plussage

Sometimes the basic has an addition to recognise an aspect of working conditions or employee capability. Payments for educational qualifications and for supervisory responsibilities are quite common. There is also an infinite range of what are sometimes called ‘fudge’ payments, whereby there is an addition to the basic as a start-up allowance, mask money, dirt money, and so forth.

4.3. Benefits

Extras to the working conditions that have a cash value are categorised as benefits and can be of great variety. Some have already been mentioned; others include luncheon vouchers, subsidised meals, discount purchase schemes and the range of welfare provisions such as free chiropody and cheap hairdressing.

4.4. Premia

Where employees work at inconvenient times – or on shifts or permanently at night – they receive a premium payment as compensation for the inconvenience. This is for inconvenience rather than additional hours of work. Sometimes this is built into the basic rate or is a regular feature of the contract of employment so that the payment is unvarying. In other situations shift working is occasional and short-lived, making the premium a variable element of payment. Shift premia are received by 11 per cent of UK workers (Grabham 2003, p. 399), accounting on average for around 6 per cent of their total pay (Office for National Statistics 2006, p. 9).

4.5. Overtime

It is customary for employees working more hours than are normal for the working week to be paid for those hours at an enhanced rate, usually between 10 and 50 per cent more that the normal rate according to how many hours are involved. Seldom can this element be regarded as fixed. No matter how regularly overtime is worked, there is always the opportunity for the employer to withhold the provision of overtime or for the employee to decline the extra hours. Overtime is earned by over a quarter of the UK workforce, more than two-thirds of the recipients being men (Grabham 2003, p. 398; Office for National Statistics 2006, p. 9). It is particularly associated with less-well-paid manual work. Where overtime is paid it tends to account for a major portion of an individual’s gross pay (18.2 per cent on average in 2006).

4.6. Incentive

Incentive is here described as an element of payment linked to the working performance of an individual or working group, as a result of prior arrangement. This includes most of the payment-by-results schemes that have been produced by work study, as well as commission payments to salespeople, skills-based pay schemes and performance-related

pay schemes based on the achievement of agreed objectives. The distinguishing feature is that the employee knows what has to be done to earn the payment, though he or she may feel very dependent on other people, or on external circumstances, to receive it. Forty-four per cent of employees in the private sector, compared with only 19 per cent in the public sector receive a portion of their pay via some sort of incentive (Kersley et al. 2006, p. 190). Around 10 per cent of pay on average takes this form (Office for National Statistics 2006, p. 9).

4.7. Bonus

A different type of variable payment is the gratuitous payment by the employer that is not directly earned by the employee: a bonus. The essential difference between this and an incentive is that the employee has no entitlement to the payment as a result of a contract of employment and cannot be assured of receiving it in return for a specific performance. The most common example of this is the Christmas bonus.

We include profit sharing under this general heading although the ownership of shares confers a clear entitlement. The point is that the level of the benefit cannot be directly linked to the performance of the individual. Rather, it is linked to the performance of the business. In some cases the two may be synonymous, with one dominant individual determining the success of the business, but there are very few instances like this, even in the most feverish imaginings of tycoons. Share ownership or profit sharing on an agreed basis can greatly increase the interest of the employees in how the business is run and can increase their commitment to its success, but the performance of the individual is not directly rewarded in the same way as in incentive schemes.

5. THE IMPORTANCE OF EQUITY

Whatever methods are used to determine pay levels and to decide what elements make up the individual pay package, employers must ensure that they are perceived by employees to operate equitably. It has long been established that perceived inequity in payment matters can be highly damaging to an organisation. Classic studies undertaken by J.S. Adams (1963) found that a key determinant of satisfaction at work is the extent to which employees judge pay levels and pay increases to be distributed fairly. These led to the development by Adams and others of equity theory which holds that we are very concerned that rewards or ‘outputs’ equate to our ‘inputs’ (defined as skill, effort, experience, qualifications, etc.) and that these are fair when compared with the rewards being given to others. Where we believe that we are not being fairly rewarded we show signs of ‘dissonance’ or dissatisfaction which leads to absence, voluntary turnover, on- job shirking and low-trust employee relations. It is therefore important that an employer not only treats employees equitably in payment matters but is seen to do so too.

While it is difficult to gain general agreement about who should be paid what level of salary in an organisation, it is possible to employ certain clear principles when making decisions in the pay field. Those that are most important are the following:

- a standard approach for the determination of pay (basic rates and incentives) across the organisation;

- as little subjective or arbitrary decision making as is feasible;

- maximum communication and employee involvement in establishing pay determination mechanisms;

- clarity in pay determination matters so that everyone knows what the rules are and how they will be applied.

These are the foundations of procedural fairness or ‘fair dealing’. In establishing pay rates it is not always possible to distribute rewards fairly to everyone’s satisfaction, but it should always be possible to distribute rewards using procedures which operate equitably. You will find further information and discussion exercises about the way people perceive their pay and talk about it on this book’s companion website, www.pearsoned.co.uk/torrington.

Source: Torrington Derek, Hall Laura, Taylor Stephen (2008), Human Resource Management, Ft Pr; 7th edition.

Well I truly enjoyed studying it. This tip provided by you is very constructive for proper planning.