1. Taxation of U.S. Resident Aliens or Citizens

U.S. citizens and resident aliens are taxed on their worldwide income. In general, the same rules apply irrespective of whether the income is earned in the United States or abroad. Foreign tax credits are allowed against U.S. tax liability to mitigate the effects of taxes by a foreign country on foreign income. This also avoids double taxation of income earned by a U.S. citizen or resident, first in a foreign country where the income is earned (foreign source income) and then in the United States. Such benefits are available mainly to offset income taxes paid or accrued to a foreign country and may not exceed the total U.S. tax due on such income.

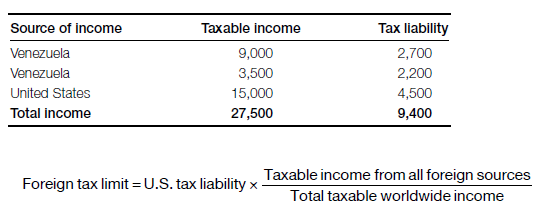

Example: Nicole, who is a U.S. resident, has a green card. She exports appliances (e.g., washers, dryers, stoves) to Venezuela and occasionally receives service fees for handling the maintenance and repairs at the clients’ locations in Caracas and Valencia. Last year, she received $9,000 in export revenues (taxable income) and $3,500 in service fees (taxable income). No foreign tax was imposed on Nicole’s export receipt of $9,000. However, she paid $2,200 in taxes to Venezuela on the service fees. Nicole also received $15,000 from her parttime teaching job at a community school (taxable income). Assume a 30 percent U.S. tax rate.

The credit is the lesser of creditable taxes paid ($2,200) or accrued to all foreign countries (and U.S. possessions) or the overall foreign tax credit limitation ($3,750). The foreign tax credit limitation = 30 percent (27,500) x 12,500/27,500 = $3,750.

If the foreign tax credit limitation is lower than the foreign tax owed (i.e., suppose the foreign tax is greater than $3,750), the excess amount can be carried back two years and forward five years to a tax year in which the taxpayer has an excess foreign credit limitation.

2. Taxation of Foreign Persons in the United States (Nonresident Aliens, Branches, or Foreign Corporations)

Foreign firms use different channels when marketing their products in the United States. They often begin selling goods through independent distributors until they gain sufficient resources and experience. As their export volume grows, they may wish to directly export to their U.S. customers and market their products by having their employees occasionally travel to the United States in order to contact potential clients, identify growing markets, or negotiate sales contracts. As the company becomes more successful in the market, it may decide to establish a branch or subsidiary in the United States.

Foreign persons engaged in U.S. trade or business are subject to U.S. taxation on the income that is “efficiently connected” with the conduct of U.S. trade or business. This includes U.S.-source income derived by a nonresident alien, foreign corporation, or U.S. branch from the sale of goods or provision of services. “Effectively connected income” may be extended beyond U.S.-source income to include certain types of foreign-source income that was facilitated by use of a fixed place of business or office in the United States.

Example: Amin, a Brazilian software exporter, opens a small sales office in Hammond, Indiana, in order to sell in the United States and Canada. Canadian sales (foreign-source income) in this case are generally considered “effectively connected,” since income is produced through the U.S. sales office in Indiana. Amin’s sales in the United States (through a U.S. branch or subsidiary) are also subject to U.S. tax because they result from permanent establishment in the United States or income from U.S. trade or business.

A foreign corporation or nonresident alien that exports goods or services to the United States through a fixed place of business or office can claim deductions for expenses, losses, and foreign taxes or can claim a tax credit for any foreign income taxes, such as foreign- and U.S.-source effectively connected income. The credits are not used to offset U.S. withholding or branch profits tax and are allowable only against U.S. taxes on “effectively connected income.” While a tax deduction reduces taxable income by the amount of a given expense, tax credits are a dollar-for-dollar reduction of U.S. income tax by the amount of the foreign tax.

Model tax treaties that the United States entered into with many trading nations contain the following common provisions:

- Foreign person’s (nonresident alien, foreign corporation, U.S. branch) export profits are exempt from U.S. tax unless such profits are attributable to a permanent establishment maintained in the United States, that is, a fixed place of business, or when U.S.-dependent agents have authority to conclude sales contracts on behalf of the company.

Example: Donga Inc., a trading company incorporated in Monaco, exports ceiling fans to the US. Its sales agents spend two months of every year traveling across the US to market/promote sales with major clients. When they receive orders, they forward them to the home office for final approval. The agents do not sign purchase orders or sales contracts.

Donga Inc. is not subject to U.S. taxes since (a) the agents do not have contracting authority and (b) the company does not have a permanent establishment in the United States.

- Marketing products in the United States through independent agents or distributors does not create a permanent establishment and thus there is no tax liability in the United States.

- Income from personal services provided by nonresident aliens in the United States are normally exempt unless the employee is present in the United States for more than 183 days or paid by a U.S. resident. Income derived by professionals (e.g., accountants, doctors) are exempt unless attributable to a fixed place of business in the United Sates.

3. Taxation of U.S. Exports

In general, U.S. companies that export their goods overseas will incur no tax liability in the importing country if:

- They undertake their exports through independent distributors (they have a nontaxable presence in the importing country).

- Their agents/employees overseas do not have authority to conclude sales contracts on behalf of the U.S. exporter.

- The services performed are not attributable to a fixed place of business in the host country.

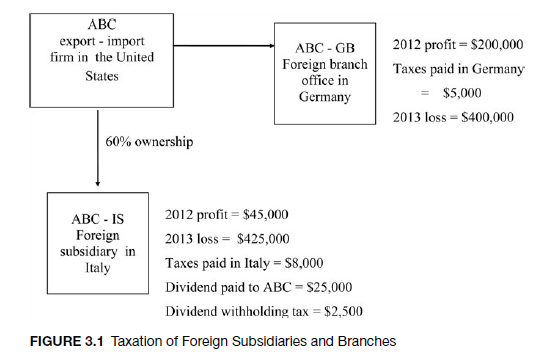

An export-import firm may enter a foreign market by establishing a branch in a foreign country. Branches are often used to retain exclusive control of overseas operations or to deduct losses on initial overseas activities. However, they can be incorporated abroad when such operations become profitable to enable the firm to defer any U.S. income taxes owed on profits until they are remitted to the United States. A branch is not a separate corporation; it is considered an extension of the domestic corporation. One of the major disadvantages of operating a branch is that it exposes the domestic firm to liability in a foreign country. Foreign branch taxes are paid when they are earned (not when remitted to the United States, as in the case of a foreign corporation), and losses are reported when incurred. Foreign taxes paid or accrued on branch profits are eligible for foreign tax credits (Figure 3.1).

An export-import firm can enter a foreign market by establishing a separate corporation (subsidiary) to conduct business. The parent corporation and the subsidiary are separate legal entities, and their individual liabilities are limited to the capital investment of each respective firm. Foreign taxes are paid when the subsidiary receives the income, but U.S. taxes are paid when distributed to shareholders as a dividend. Foreign taxes paid (a ratable share) are eligible for a tax credit at the time of distribution of dividend to the U.S. taxpayer. A U.S. shareholder (parent firm) can also claim a proportional share of a dividends-received deduction.

- The 2012 profit ($200,000) of the German Branch is taxable to ABC export-import firm in 2012. Remittance of reported earnings to the United States is not required for tax purposes. However, 2012 profits earned by the Italian subsidiary are subject to tax in the United States only when remitted; that is, taxes can be deferred until remitted to the U.S. parent.

- The 2013 losses by ABC-GB can be used to offset ABC’s 2013 taxable income from its U.S. operations. However, ABC-IS’s losses cannot be used to reduce ABC’s 2013 taxable income. The $425,000 loss incurred can be used only to reduce profits earned in other years and distributed as dividend to ABC Company.

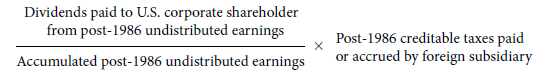

- Taxes paid by ABC-GB to Germany can be claimed to offset ABC’s U.S. taxes due on its profits. In the case of ABC-IS’s taxes paid on its profits to Italy, ABC can claim a foreign tax credit for the taxes withheld on its dividend receipts for the given year. This does not reduce all or most of the foreign taxes incurred or paid on the subsidiary’s profits, since it is limited only to taxes withheld from a foreign subsidiary’s dividend remittances. The introduction of the “deemed paid foreign tax credit” was intended to remedy this inequity. Under this method, the U.S. shareholder (ABC) will be deemed to have paid a portion of ABC-IS’s foreign taxes corresponding to the proportion of dividends received and not on any withholding taxes on the dividends distributed. However, the deemed paid foreign tax credit is available to U.S. companies that own at least 10 percent of the foreign subsidiary’s voting stock at the time of distribution and is based only on actual dividends paid. It is also limited only to corporate U.S. shareholders.

Deemed paid tax credit (DPTC) is calculated as follows:

4. Taxation of Controlled Foreign Corporations

A controlled foreign corporation (CFC) is a foreign corporation in which U.S. shareholders own more than 50 percent of the voting stock or more than 50 percent of the value of the outstanding stock in any of the foreign corporation’s tax year. Rules governing CFCs are concerned with preventing U.S. businesspersons from escaping high marginal tax rates in the United States by operating through controlled corporations in a foreign country that imposes little or no tax. The parent company could sell goods or services to a foreign subsidiary and manipulate prices so that most of the profits are allocated to the subsidiary in a country that imposes little or no tax, thus avoiding U.S. and foreign taxes. The CFC could also be used as a base company to make sales outside its country of incorporation or as a holding company to accumulate passive investment income such as interest, dividends, rent, and royalties.

U.S. shareholders must report their share of CFC’s subpart F income each year. Subpart F income includes foreign base company income (foreign base sales, services, shipping, and personal holding company income), CFC’s income from insurance of U.S. and foreign risks, boycott-related income and bribes, and other illegal payments.

A U.S. shareholder is subject to tax on the subpart F income only when the foreign corporation is a CFC for at least thirty days during its tax year. A U.S. shareholder of a CFC must then include his or her pro rata share of the subpart F income as a deemed dividend that is distributed on the last day of the CFC’s tax year or the last day on which CFC’s status is retained (McDaniel et al., 1981; Ogley, 1995).

Example: Monaco corporation, located in Hong Kong, is a CFC owned by XYZ Company of San Diego, California. Monaco corporation buys computer parts from XYZ Company and sells about 80 percent of the parts in other Asian countries. The remainder is sold to retailers in Hong Kong. Profits earned from sales in foreign countries are foreign base sales income, that is, subpart F income, and taxable to XYZ Company during the current year. Sales to foreign countries of goods manufactured by Monaco in Hong Kong would not constitute foreign base sales income.

5. Taxation of Domestic International Sales Corporations

Taxation of domestic international sales corporations (DISCs) is discussed in chapter 15.

6. Deductions and Allowances

Export-import businesses may deduct ordinary and necessary expenses. Ordinary and necessary expenses are defined by the Internal Revenue Service as follows:

An ordinary expense is one that is common and accepted in your type of business, trade or profession. A necessary expense is one that is helpful and appropriate for your trade, business, or profession. An expense does not have to be indispensable to be considered necessary. (Internal Revenue Service, 2012a, p. 6)

When one starts the export-import business, all costs are treated as capital expenses. These expenses are a part of the investment in the business and generally include:

- The cost of getting started in the business before beginning export-import operations such as market research, expenses for advertising, travel, utilities, repairs, employees’ wages, salaries, and fees for executives and consultants.

- Business assets such as building, furniture, and trucks and the costs of making any improvements to such assets, for example, a new roof or new floor. The cost of the improvement is added to the base value of the improved property.

The cost of specific assets can be recovered through depreciation deductions. Other startup costs can be recovered through amortization; that is, costs are deducted in equal amounts over 60 months or more. Organizational costs for a partnership (expenses for setting up the partnership) or corporation (e.g., costs of incorporation, legal and accounting fees) can be amortized over sixty months and must be claimed on the first business tax return. Once the business has started operations, standard business deductions are applied against gross income. Standard business deductions include the following:

- General and administrative expenses: Office expenses such as telephones, utilities, office rent, legal and accounting expenses, salaries, professional services, and dues. These also include interest payments on debt related to the business, taxes (real estate and excise taxes, estate and employment taxes), insurance, and amortization of capital assets.

- Personal and business expenses: If an expense is incurred partly for business and partly for personal purposes, only the part that is used for business is deductible. If the export-import business is conducted from one’s home, part of the expense of maintaining the home could be claimed as a business expense. Such expenses include mortgage interest, insurance, utilities, and repairs. To successfully claim such limited deductions, part of the home must be used exclusively and regularly as the principal place of business for the export-import operation or as a place to meet customers or clients. Similarly, automobile expenses to conduct the business are deductible. If the car is used for both business and family transportation, only the miles driven for the business are deductible as business expenses. Automobile-related deductions also include depreciation on the car; expenses for gas, oil, tires, and repairs; and insurance and registration fees (Internal Revenue Service, 2012b).

- Entertainment, travel, and related business expenses: Expenses incurred entertaining clients for promotion, travel expenses (the cost of air, bus, taxi fares), as well as other related expenses (dry cleaning, tips, subscriptions to relevant publications, convention expenses) are tax deductible (Internal Revenue Service, 2012c).

If deductions from the export-import business are more than the income for the year, the net operating loss can be used to lower taxes in other years. All of these expenses have to be specifically allocated and apportioned between foreign- and domestic-source income.

7. International Transfer Pricing

Transactions between unrelated parties and prices charged for goods and services tend to reflect prevailing competitive conditions. Such market prices cannot be assumed when transactions are conducted between related parties, such as a group of firms under common control or ownership. If a parent company sells its output to a foreign marketing subsidiary at a higher price, it moves overall gains to itself. If it charges a lower price, it shifts more of the overall gains to the subsidiary. Even though transfer prices do not affect the combined income or absolute amount of gain or loss among related persons or “controlled group of corporations,” they do shift income among related parties in order to take advantage of differences in tax rates (International Perspective 3.2).

In the example, the combined income remains at $1,000 for the steel export regardless of the transfer price used to allocate income between the parent and the subsidiary. If the tax rate is 30 percent in the United States and 40 percent in Spain, the U.S. parent company can use the higher transfer price for its controlled sale (Option B) to reduce its world wide taxes:

Option A: 1000 x 40% = $400 (Spain’s rate)

Option B: 1000 x 30% = $300 (U.S. rate)

In cases where U.S. companies operate in low-tax jurisdictions, income can be shifted to a low-tax subsidiary. This has the advantage of deferring the U.S. tax until the foreign subsidiary repatriates its earnings through dividend distribution.

U.S. regulation (Section 482) on transfer pricing is largely intended to ensure that taxpayers report and pay taxes on their actual share of income arising from controlled transactions. The appropriateness of any transfer price is evaluated on the basis of the arm’s-length or market-value standard. For example, in the case of loans extended by a U.S. parent company

to its overseas subsidiary, the Internal Revenue Service has successfully imposed an arm’s- length interest charge (a charge that would be paid by unrelated parties under similar circumstances).

8. Tax Treaties

Income tax treaties are entered into by countries to reduce the burden of double taxation on the same activity and to exchange information to prevent tax evasion. Tax-treaty partners generally agree on rules about the types of income that a country can tax and the provision of a tax credit for any taxes paid to one country against any taxes owed in another country.

The United States has entered into a number of tax treaties with about sixty countries. They include Canada, China, EU countries, India, Japan, South Korea, Mexico, New Zealand, South Africa, and many of the transition economies of Central and Eastern Europe. In most countries, the treaty prevails over domestic law. In the United States, if there is a conflict between a treaty provision and domestic law, whichever is the most recently enacted governs the transaction.

The following are some of the common treaty provisions with regard to business profits:

- The export profits of an enterprise of one treaty country shall be taxable only in that country unless the enterprise carries on business in the other treaty country through a permanent establishment situated therein. The importing country may tax the enterprise’s profits that are attributable to that permanent establishment (U.S. Government, 1966, Part 7.1).

- Permanent establishment is meant to describe a fixed place of business through which the business of an enterprise is wholly or partially discharged. It includes a place of management, a branch, an office, a factory, a workshop, a mine, or any other place of extraction of natural resources. It is assumed to be a permanent establishment only if it lasts or the activity continues for a period of more than twelve months (U.S. Model Income Tax Treaty, 5.3).

- Permanent establishment shall not include certain auxiliary functions such as purchasing, storing, or delivering inventory (U.S. Model Income Tax Treaty, 5.4).

- An enterprise is deemed to have a permanent establishment in a treaty country if its employees conclude sales contracts in its name. If a Canadian exporter sends its sales agents to enter into a contract with a U.S. firm in New York, the Canadian company shall be deemed to have a permanent establishment in the United States. even if it does not have an office in the United States (U.S. Model Income Tax Treaty, 5.5).

- Permanent establishment is not imputed in cases where a product is exported through independent brokers, or distributors regardless of whether these independent agents conclude sales contracts in the name of the exporter (U.S. Model Income Tax Treaty, 5.6).

Source: Seyoum Belay (2014), Export-import theory, practices, and procedures, Routledge; 3rd edition.

Pretty great post. I simply stumbled upon your blog and wished to say that I have really enjoyed surfing around your weblog posts. In any case I’ll be subscribing in your rss feed and I hope you write once more very soon!

As I web site possessor I believe the content matter here is rattling fantastic , appreciate it for your hard work. You should keep it up forever! Best of luck.