AR can be thought of as a process consisting of at least two analytically distinct phases. The first involves the clarification of an initial research question, whereas the second involves the initiation and continuation of a social change and meaning construction process. This does not mean that the problem definition process is ever final; in fact, a good sign of the learning taking place in an AR project is when the initial questions are reshaped to include newly discovered dimensions.

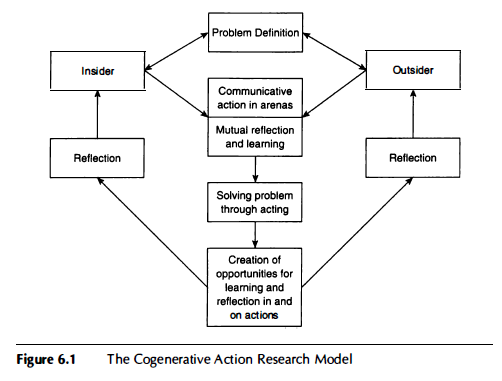

We can visualize the cogenerative model as shown in Figure 6.1. What follows is a thorough discussion of the elements that make up the cogenerative model.

This model identifies two main groups of actors. The insiders are the focal point of every AR project. They are the “owners” of the problem, but they are not homogeneous, egalitarian, or in any way an ideal group. They simply “own” the problem. Outsiders are the professional researchers who seek to facilitate a colearning process aimed at solving local problems and to make contributions to the scientific discourse. Insiders and outsiders are both equal and different. They are different because most insiders have to live directly with the results of any change activity in a project, whereas most outsiders can leave. Another difference is that the insiders have the central influence on what the focus of the research activity should be.

1. PROBLEM DEFINITION

The question to be researched must be of major importance to the participants or the process will go nowhere. Once it is established, we can gain additional leverage by using relevant bodies of professional knowledge in the field, as in the case of the organizational culture literature in the Mondragon project (see Chapter 3).

We have argued that anAR process deals with solving pertinent problems for the participants. In this respect, the whole research process emerges from demands arising outside the academy. This contrasts with conventional social science, where research problems are defined as much by developments within the disciplines as by external social forces. Yet AR professionals do not just blindly accept any problem formulation forwarded by the local participants. We view the problem definition process as the first step in a mutual learning process between insiders and outsiders. To facilitate a process in which insider knowledge is clarified in relation to outsider professional knowledge, communication procedures must permit the development of a mutually agreed-on problem focus. These procedures include rules of democratic dialogue, which involve openness, mutual support, and shared “air time.” A first working definition of the problem under study comes out of a discourse through which knowledge held by insiders and outsiders cogenerates a new, mutual understanding through their communication with each other.

2. COMMUNICATION ARENAS

Central to the cogenerative process in AR is its ability to create room for learning processes resulting in interpretations and action designs that participants trust. To this end, the “arena” for communication between the groups of actors must be properly configured. ( See Figure 6. 1 . ) These are locations where the involved actors encounter each other in a material setting for the purpose of ca rrym· g on AR. The arena can be a meeting between two and more people, a team-building session, a search conference, a task force meeting, a leadership meeting’ or a pu hiI’ c comm unity meeting. The key point is that an arena allows communicative actions to take place in an environment structured for cogenerative learning and research.

The central challenge in any AR project is to design adequate arenas for communication about the problems of major importance to the local participants. Arenas must be designed to match the needs at issue. There is no “one- size-fits-all” approach. If the challenge is to engage a whole organization in an organizational development process, it generally is smart to gather everyone in a large room to work out the plans for a new project. However, dealing with conflicts between managers in an organization might better be addressed in a leadership group format. Selecting and structuring proper arenas depends on the professional skills and experience of the AR facilitator, and good and appropriate choices are vital for a successful AR project.

In arenas, communication between insiders and outsiders aims to produce learning and open up a process of reflection for the involved parties. These discussions and reflections are the engine for ongoing learning cycles. The initial problem focus suggests a design for an arena for discourse. The subsequent communication produces understandings that help move toward problem solutions, creating new experiences for both the insiders and the professional researchers to reflect on.

The discourses that take place in these arenas are inherently unbalanced. The insiders have a grounded understanding of local conditions far beyond what any outsider ever can gain, unless he or she settles in that specific local community or organization to live. Likewise, the outside researcher brings with him or her skills and perspectives often not present in the local context, including knowledge about how to design and run learning and reflection processes.

The asymmetry in skills and local knowledge is an important force in cogenerating new understandings as the parties engage each other to make sense out of the situation. The democratic ideals of AR research also mandate a process in which the outsider gradually lets go of control so that the insiders can learn how to control and guide their own developmental processes. These ideals also promote the development of the insiders’ capacities to sustain more complex internal dialogues with a more diverse set of participants than would have been the case without this set of learning experiences.

The asymmetrical situation between outsiders and insiders (Markova & Foppa, 1991) lies at the center of complex social exchanges. The outsider designs training sessions that make transfer of knowledge possible and uses his or her influence to direct the developmental process. The professional researcher necessarily exercises power in this process. Though the outsider does not have a formal position in the local organizational hierarchy, she or he exerts influence through participant expectations that she or he play a major role in designing and managing the change processes. Dealing honestly and openly with the power those expectations grant to the researcher is a central challenge inAR change processes. This has a significant effect on the development of local learning processes, and this power is easy to abuse.

At the beginning of a research process, the outsider makes decisions and teaches and trains local participants on topics that both consider important. At the same time, the outsider is responsible for encouraging insiders to take control of the developmental process. The professional researcher’s obligation to let go of the group near the end is sometimes difficult to live up to, but often this is easier to achieve than the development of the local participants’ capability to control and direct the ongoing developmental process according to their own interests.

For participants to become active players in a change process, they must exercise power. The initially asymmetrical situation between insiders and outsiders can be balanced only by the transfer of skills and knowledge from the professional researcher to the participants and the transfer of information and skills from the local participants to the outside researcher. In the end, to be sustainable, the process must be taken over by the local participants. The AR process cannot fulfill its democratic obligations unless the main thrust of the process is to increase the participants’ control over ongoing knowledge production and action. Standard training in conventional social science research and the whole academic reward system focus strongly on retaining control over both the design and the execution of research activities, treating this control as a hallmark of professional competence.

The struggle to solve important local problems shapes the ground for new understandings, hence the double feedback loops in Figure 6.1. That is to say that, through actions taken as a result of the cogenerative processes, the participants learn new things about the problems they are facing, often revising their understandings in fundamental ways. The outcomes of this collective process of action and reflection support the creation of new shared understandings. The larger this shared ground is, the more fruitful the communication has been and the greater the likelihood is that further insights can be developed through reflection and actions based on this shared knowledge. This in turn can open up new ways of formulating the AR problems and thus result in ongoing learning for all parties, including the professional researcher.

3. FEEDBACK

The feedback loops are similar for both insiders and outsiders, but the interests they have in and the effects they experience from the communication can be quite different. For insiders, it may be central to improve their action- knowledge capabilities, whereas the outsiders may, through the reflection process, produce meaning (publications or insights) for the research community. Both of these reflective processes are then fed back into the communicative process, further shaping the arenas for new dialogues aimed at either redefining the initial problem statement or improving the local problem-solving capacity. Cycles like this continue throughout the life of a project.

4. CREATING ARENAS

A major challenge in AR is to find a good first question that is at least partly shared among the involved parties, particularly at the outset. There are several obstacles to overcome. The conventional training of academic researchers generally makes them experienced debaters with lots of practice in managing conceptual models. This can create a situation of communicative domination that undermines the cogenerative process. This situation has been called “model monopoly” by Br\then (1973 ). He identifies and analyzes situations where one side dominates and, through skills in communication and the handling of certain kinds of conceptual models, constantly increases the distance between insiders and outsiders. In addition, the professional’s social prestige and years of formal training may convince people to accept a particular point of view too easily. When this happens, it is a serious threat to the AR process because it distracts attention from local points of view that are central to the initiation of any AR process. Skilled action researchers develop the ability to help articulate and make sense of local models and are sure they are well articulated in the communicative process.

Thus, AR is a strategy for orchestrating a variety of techniques and change-oriented work forms in an intentionally designed process of cogenerative learning that examines pressing problems, designs action strategies based on the research on the problems, and then implements and evaluates the liberating forms of action that emerge. While conventional social research is oriented around professional enlightenment, AR is oriented to achieving particular social goals, not just to the generation of knowledge to satisfy curiosity or to meet some particular professional academic need.

5. WHAT ACTION RESEARCHERS MAY NOT DO

Though we have asserted that any kind of social research techniques and processes are deployable in AR, there are constraints on how action researchers can operate. Certain kinds of“double-blind” methods are unacceptable if they involve purposely depriving some group of stakeholders of support or information that affects them in important ways. Controlled processes solely for the purpose of advancing professional social sciences or of satisfying the curiosity of outsiders with no benefit to local stakeholders are not permissible. Action researchers may not make demands of local stakeholders that they are not willing to make of themselves. If disclosure of interests and aims is part of the structuring of the arena, the action researchers must also disclose their interests and aims in the situation. Action researchers may not extract or expropriate the intellectual property created in the AR process. All results are co-owned in this cogenerative process, and complex negotiations about the handling of the generated results in public and in print are a sine qua non of AR.

Source: Greenwood Davydd J., Levin Morten (2006), Introduction to Action Research: Social Research for Social Change, SAGE Publications, Inc; 2nd edition.

Greate article. Keep posting such kind of information on your blog.

Im really impressed by it.

Hi there, You have done a fantastic job. I’ll definitely digg it and for

my part recommend to my friends. I am sure they’ll be benefited from this web site.