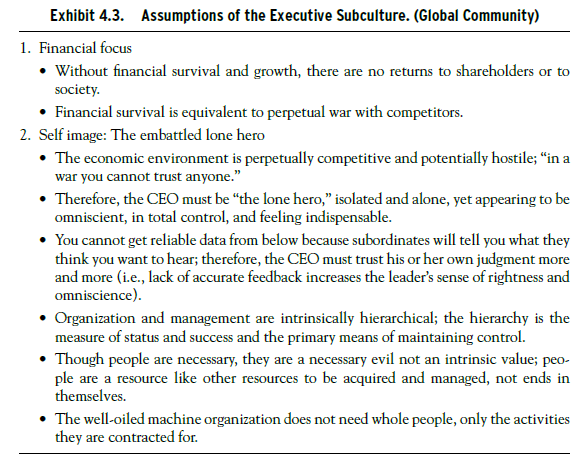

A third generic subculture that exists in all organizations is the executive subculture based on the fact that top managers in all organizations share a similar environment and similar concerns. Sometimes, this subculture is represented by just the CEO and his or her executive team. The executive worldview is built around the necessity to maintain the financial health of the organization and is fed by the preoccupations of boards, of investors, and of the capital markets. Whatever other preoccupations executives may have, they cannot get away from having to worry about and manage the financial issues of the survival and growth of their organization. In private enterprise, the executives have to worry specifically about profits and return on investments, but financial issues around survival and growth are just as salient in the public and nonprofit enterprise. The essence of this executive subculture is described in Exhibit 4.3.

The basic assumptions of the executive subculture apply particularly to CEOs who have risen through the ranks and have been promoted to their jobs. Founders of organizations or family members who have been appointed to these levels exhibit different kinds of assumptions and often can maintain a broader focus (Schein, 1983). The promoted CEO adopts the exclusively financial point of view because of the nature of the executive career. As managers rise higher and higher in the hierarchy, as their level of responsibility and accountability grows, they not only have to become more preoccupied with financial matters, but they also discover that it becomes harder and harder to observe and influence the basic work of the organization. They discover that they have to manage at a distance, and that discovery inevitably forces them to think in terms of control systems and routines, which become increasingly impersonal. Because accountability is always centralized and flows to the tops of organizations, executives feel an increasing need to know what is going on while recognizing that it is harder and harder to get reliable information. That need for information and control drives them to develop elaborate information systems alongside the control systems and to feel increasingly alone in their position atop the hierarchy.

Paradoxically, throughout their career, managers have to deal with people and surely recognize intellectually that it is people who ultimately make the organization run. First-line supervisors, especially, know very well how dependent they are on people. However, as managers rise in the hierarchy, two factors cause them to become more “impersonal.” First, they become increasingly aware that they are no longer managing operators but other managers who think like they do, thus making it not only possible but likely that their thought patterns and worldview will increasingly diverge from the worldview of the operators. Second, as they rise, the units they manage grow larger and larger until it becomes impossible to know everyone personally who works for them. At some point, they recognize that they cannot manage all the people directly and, therefore, have to develop systems, routines, and rules to manage “the organization.” People increasingly come to be viewed as “human resources” and are treated as a cost rather than a capital investment.

The executive subculture thus has in common with the engineering subculture a predilection to see people as impersonal resources that generate problems rather than solutions. Or, another way to put this point is to note that in both the executive and engineering subcultures, people and relationships are viewed as means to the end of efficiency and productivity, not as ends in themselves. Both of these subcultures also have in common their occupational base outside the particular organization in which they work. Even if a CEO or engineer has spent his or her entire career inside a given organization, he or she still tends to identify with the occupational reference group outside the organization. For example, when conducting executive programs for CEOs, CEOs will only attend if other CEOs will be there. Similarly, design engineers count on being able to go to professional conferences where they will learn of the latest technologies from their outside professional colleagues.

I have highlighted these three subcultures because they are often working at cross purposes with each other, and we cannot understand the organizational culture if we do not understand how these conflicts are dealt with in the organization. Many problems that are attributed to bureaucracy, environmental factors, or personality conflicts among managers are in fact the result of the lack of alignment between these subcultures. So when we try to understand a given organization, we must consider not only the overall corporate culture but also the identification of subcultures and their alignment with each other.

For example, in DEC, the growth period worked so smoothly because the designers, operators, and executives all came from electrical engineering and found it very easy to run the company from an engineering point of view. As they grew and had to compete on costs with other organizations, it became more important to honor the executive subculture, but because the founder and CEO was still thinking like an engineer, the financial managers within DEC had a very hard time getting their point of view across. Similarly, the sales and marketing organizations had developed subcultures but had relatively little clout with the increasingly strong engineering subculture. One way of understanding DEC ’s ultimate economic failure is to realize that it was dominated by the engineering subculture to the end; neither the operators nor the executives were ever in control.

Furthermore, conflicts arose between powerful subcultures within the engineering function because of the assumption that internal competition was good, that the market would ultimately decide what products to continue to build, that innovation and growth would absorb the increasing costs of doing “everything,” and that everyone should “do the right thing.” The DEC culture empowered people, so people who had been successful and had built up powerful groups within DEC were now convinced that they had the answer to DEC’s future. As technology became more complex and as costs became more of a factor because of competition, it was no longer possible to support the several projects that powerful groups within engineering advocated, resulting in the reality that all of them were too slow in getting to the market. In effect, DEC had never developed a strong executive subculture and could not, therefore, control the conflict between the warring engineering subcultures.

The subculture situation in Ciba-Geigy was very different because it was a much older more differentiated organization. However, one could clearly see the impact of the engineering and operator subcultures in that they both derived from the occupational culture of chemical engineering. Science and chemistry were sacred cows, which made it much harder for the executive subculture to manage acquisitions if they were financially successful but did not fit the cultural ideals of producing important products. Ciba-Geigy had acquired the American air freshener company Airwick and then made it difficult for Airwick to function. For example, the CEO of Airwick France needed an accounting system that was more responsive than the one Ciba- Geigy was using and was told by the corporate head of accounting that the more ponderous slower corporate system “should be adequate.” As we will see later, only the subculture of law began to have significant influence on executive decision making as the organization evolved.

Beyond the three generic subcultures that we have discussed, organizations that have any history and growth will have evolved other subcultures that should be analyzed to understand the dynamics of how things work. For example, in most hospital systems, there are “ doctors ” and “ nurses ” subcultures that will be in varying degrees of alignment with each other. In banks, there is a subculture around the lending function and a different one around the investment function. In many production organizations, the maintenance organization develops its own subculture, and in universities, each department develops a subculture based on the subject matter of its teaching and research. Though the tenure requirements might be the same for all faculty, the subcultures show up in the actual criteria used in assessing what kind of work qualifies. In mathematics, it might be one brilliant solution of an old problem; in science, the evolution of a new theory; in engineering, the development of a new practical solution; and in the humanities, the publication of one or more books. Though it might be tempting to think of “academia” as one culture because of some common basic assumptions, the reality is that different universities and different departments generate different cultures.

Source: Schein Edgar H. (2010), Organizational Culture and Leadership, Jossey-Bass; 4th edition.

Well I really liked studying it. This tip provided by you is very helpful for good planning.

Good write-up, I’m normal visitor of one’s site, maintain up the nice operate, and It’s going to be a regular visitor for a lengthy time.