1. LEADERSHIP AND MANAGEMENT

Northouse (2006) suggests that there are four components that characterise leadership: that leadership is a process; it involves influence; it occurs within a group context; and it involves goal attainment. This corresponds with Shackleton’s (1995) definition, which we shall use as a working definition for the remainder of the chapter:

Leadership is the process in which an individual influences other group members towards the attainment of group or organizational goals. (Shackleton 1995, p. 2)

This definition is useful as it leaves open the question of whether leadership is exercised in a commanding or a facilitative manner. It does suggest, however, that the leader in some way motivates others to act in such a way as to achieve group goals.

The definition also makes no assumptions about who the leader is; it may or may not be the nominal head of the group. Managers, therefore, may or may not be leaders, and leaders may or may not be managers. Some authors distinguish very clearly between the nature of management and the nature of leadership but this draws on a particular perspective, that of the transformational leader, and we will consider this in the section on whether the organisation needs heroes. This is a school of thought that concentrates on the one leader at the top of the organisation, which is very different from organisations and individuals who use the terms manager and leader interchangeably with nothing more than a vague notion that managers should be leaders. Indeed, any individual may act as a manager one day and a leader the next, depending on the situation. In addition we should not assume that leadership is always a downwards process, as sometimes employees and managers lead upwards (Hollington 2006).

The flow of articles on leadership continues unabated, but it would be a mistake to think that there is an ultimate truth to be discovered; rather, there is a range of perspectives from which we can try to make sense of leadership and motivation. Grint (1997) puts it well when he comments that

What counts as leadership appears to change quite radically across time and space. (p. 3)

In the following three sections we will look at three questions which underlie virtually all the work on leadership. First, what are the traits of a leader, or an effective leader? Second, what is the ‘best’ leadership style or behaviour? Third, if different styles are appropriate at different times, what factors influence the desired style?

2. WHAT ARE THE TRAITS OF LEADERS AND EFFECTIVE LEADERS?

Trait approaches, which were the earliest to be employed, seek to identify the traits of leaders – in other words what characterises leaders as opposed to those who are not leaders. These approaches rest on the assumption that some people were born to lead due to their personal qualities, while others are not. It suggests that leadership is only available to the chosen few and not accessible to all. These approaches have been discredited for this very reason and because there has been little consistency in the lists of traits that research has uncovered. However, this perspective is frequently resurrected.

Kilpatrick and Locke (1991), in a meta-analysis, did seem to find some consistency around the following traits: drive to achieve; the motivation to lead; honesty and integrity; self-confidence, including the ability to withstand setbacks, standing firm and being emotionally resilient; cognitive ability; and knowledge of the business. They also note the importance of managing the perceptions of others in relation to these characteristics. Northouse (2006) provides a useful historical comparison of the lists of traits uncovered in other studies. Perhaps the most well-known expression of the trait approach is the work relating to charismatic leadership. House (1976), for example, describes charismatic leaders as being dominant, having a strong desire to influence, being self-confident and having a strong sense of their own moral values. We will pick up on this concept of leadership in the later section on heroes.

In a slightly different vein Goleman (1998) carried out a meta-analysis of leadership competency frameworks in 188 different companies. These frameworks represented the competencies related to outstanding leadership performance. Goleman analysed the competencies into three groups: technical, cognitive and emotional, and found that, in terms of the ratios between the groups, emotional competencies ‘proved to be twice as important as the others’. Goleman goes on to describe five components of emotional intelligence:

- Self-awareness: this he defines as a deep understanding of one’s strengths, weaknesses, needs, values and goals. Self-aware managers are aware of their own limitations.

- Self-regulation: the control of feelings, the ability to channel them in constructive ways. The ability to feel comfortable with ambiguity and not panic.

- Motivation: the desire to achieve beyond expectations, being driven by internal rather than external factors, and to be involved in a continuous striving for improvement.

- Empathy: considering employees’ feelings alongside other factors when decision making.

- Social skill: friendliness with a purpose, being good at finding common ground and building rapport. Individuals with this competency are good persuaders, collaborative managers and natural networkers.

Goleman’s research is slightly different from previous work on the trait approach, as here we are considering what makes an effective leader rather than what makes a leader (irrespective of whether they are effective or not). It is also different in that Goleman refers to competencies rather than traits. There is a thorough discussion of competencies in Chapter 17; it is sufficient for now to say that competencies include a combination of traits and abilities, among other things. There is some debate over whether competencies can be developed in people. The general feeling is that some can and some cannot. Goleman maintains that the five aspects of emotional intelligence can be learned and provides an example in his article of one such individual. In spite of his argument we feel that it is still a matter for debate, and as many of the terms used by Goleman are similar to those of the previous trait models of leadership, we have categorised his model as an extension of the trait perspective. To some extent his work sits between the trait approach and the style approach which follows. It is interesting that a number of researchers and writers are recognising that there is some value in considering a mix of personality characteristics and behaviours, and in particular Higgs (2003) links this approach to emotional intelligence.

Rajan and van Eupen (1997) also consider that leaders are strong on emotional intelligence, and that this involves the traits of self-awareness, zeal, resilience and the ability to read emotions in others. They argue that these traits are particularly important in the development and deployment of people skills. Heifetz and Laurie (1997) similarly identify that in order for leaders to regulate emotional distress in the organisation, which is inevitable in change situations, the leader has to have ‘the emotional capacity to tolerate uncertainty, frustration and pain’ (p. 128). Along the same lines Goffee (2002) identifies that inspirational leaders need to understand and admit their own weaknesses (within reason); sense the needs of situations; have empathy and self-awareness.

3. WHAT IS THE ‘BEST WAY TO LEAD’? LEADERSHIP STYLES AND BEHAVIOURS

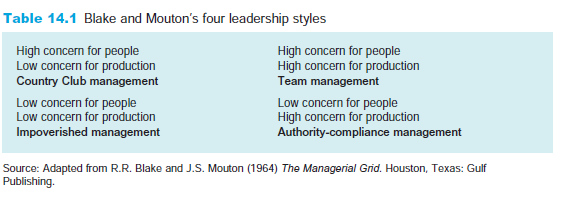

Dissatisfaction with research on leadership that saw leadership as a set of permanent personal characteristics that describe the leader led to further studies that emphasised the nature of the leadership process – the interaction between leader and follower – aiming to understand how the leaders behave rather than what they are. The first such studies sought to find the ‘best’ leadership style; from this perspective leadership comprises an ideal set of behaviours that can be learned. Fulop et al. (1999) suggest that Douglas McGregor’s (1960) work, The Human Side of Enterprise, can be understood from this perspective. McGregor argued that American corporations managed their employees as if they were work-shy, and needed constant direction, monitoring and control (theory ‘x’), rather than as if they were responsible individuals who were willing and able to take on responsibility and organise their own work (theory ‘y’). McGregor argued that the underlying assumptions of the manager determined the way he or she managed the employees and this in turn determined how the employees would react. Thus if employees were managed as if they operated on theory ‘x’ then they would act in a theory ‘x’ manner; conversely if employees were managed as if they operated on theory ‘y’ then they would respond as theory ‘y’ employees would respond. The message was that management style should reinforce theory ‘y’ and thus employees would take on responsibility, be motivated by what they were doing and work hard. Although the original book was written over forty years ago, this approach is being revisited (see, for example, Heil et al. 2000) and it fits well with the empowering or post-heroic approach to leadership that we discuss later in the chapter. Another piece of research from the style approach is that by Blake and Mouton (1964), who developed the famous ‘Managerial Grid’. The grid is based on two aspects of leadership behaviour. One is concern for production, that is, task-oriented behaviours such as clarifying roles, scheduling work, measuring outputs; the second is concern for people, that is, people-centred behaviour such as building trust, camaraderie, a friendly atmosphere. These two dimensions are at the heart of many models of leadership. Blake and Mouton proposed that individual leaders could be measured on a nine-point scale in each of these two aspects, and by combining them in grid form they identified the four leadership styles presented in Table 14.1.

Such studies, which are well substantiated by evidence, suggest that leadership is accessible for all people and that it is more a matter of learning leadership behaviour than of personality characteristics. Many leadership development courses have therefore been based around this model. However, as Northouse (2006) argues, there is an assumption in the model that the team management style (high concern for people and high concern for production; sometimes termed 9,9 management) is the ideal style; and yet this claim is not substantiated by the research. This approach also fails to take account of the characteristics of the situation and the nature of the followers.

Much of the recent work on the notion of transformational/heroic leadership, and empowering/post-heroic leadership, similarly assumes that what is being discussed is the one best way for a leader to lead, and we return to this leadership debate later on.

4. DO LEADERS NEED DIFFERENT STYLES FOR DIFFERENT SITUATIONS?

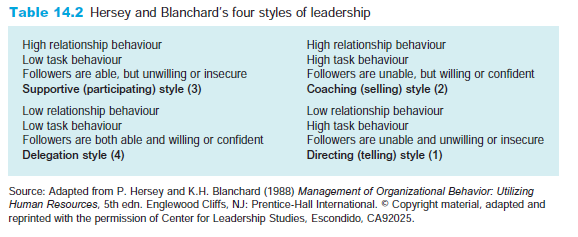

A variety of models, sometimes termed contingency models, have been developed to address the importance of context in terms of the leadership process, and as a consequence these models become more complex. Many, however, retain the concepts of production-centred and people-centred behaviour as ways of describing leadership behaviour, but use them in a different way. Hersey and Blanchard (1988) developed a model which identified that the appropriate leadership style in a situation should be dependent on their diagnosis of the ‘readiness’, that is, developmental level or maturity, of their followers. The model is sometimes referred to as ‘situational leadership’, and works on the premise that leaders can ‘adapt their leadership style to meet the demands of their environment’ (Hersey and Blanchard 1988, p. 169). Readiness of followers is defined in terms of ability and willingness. Level of ability includes the experience, knowledge and skills that an individual possesses in relation to the particular task at hand; and level of willingness encompasses the extent to which the individual has the motivation and commitment, or the self-confidence, to carry out the task. Having diagnosed the developmental level of the followers, Hersey and Blanchard suggest, the leader then adapts his or her behaviour to fit. They identify two dimensions of leader behaviour: task behaviour, which is sometimes termed ‘directive’; and relationship behaviour, which is sometimes termed ‘supportive’. Task behaviour refers to the extent to which leaders spell out what has to be done. This includes ‘telling people what to do, how to do it, when to do it, where to do it, and who is to do it’ (Hersey 1985, p. 19). On the other hand, relationship behaviour is defined as ‘the extent to which the leader engages in two-way or multi-way communication. The behaviours include listening, facilitating and supporting behaviours’ (ibid.). The extent to which the leader emphasises each of these two types of behaviour results in the usual two-by-two matrix. The four resulting styles are identified, as shown in Table 14.2.

There is an assumption that the development path for any individual and required behaviour for the leader is to work through boxes 1, 2, 3 and then 4 in the matrix.

Hersey and Blanchard produced questionnaires to help managers diagnose the readiness of their followers.

Other well-known contingency models include Fielder’s (1967) contingency model where leadership behaviour is matched to three factors in the situation: the nature of the relationship between the leader and members, the extent to which tasks are highly structured and the position power of the leader. The appropriate leader behaviour (that is, whether it should be task oriented or relationship oriented) depends on the combination of these three aspects in any situation. Fielder’s model is considered to be well supported by the evidence. The research was based on the relationship between style and performance in existing organisations in different contexts. For a very useful comparison of contingency models see Fulop et al. (1999).

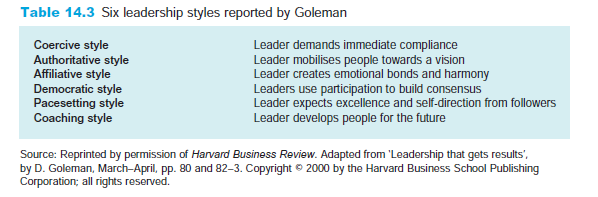

Goleman (2000) reports the results of some research carried out by Hay/McBer who sampled almost 20 per cent of a database of 20,000 executives. The results were analysed to identify six different leadership styles, which are shown in Table 14.3, but most importantly Goleman reports that ‘leaders with the best results do not rely on only one leadership style’ (p. 78).

Goleman goes on to consider the appropriate context and impact of each style, and argues that the more styles the leader uses the better. We have already reported Goleman’s work on emotional intelligence, and he links this with the six styles by suggesting that leaders need to understand how the styles relate back to the different competencies of emotional intelligence so that they can identify where they need to focus their leadership development.

Source: Torrington Derek, Hall Laura, Taylor Stephen (2008), Human Resource Management, Ft Pr; 7th edition.

You actually make it appear really easy with your presentation however I in finding this topic to be really something which I feel I’d never understand. It kind of feels too complicated and extremely wide for me. I am taking a look ahead in your next submit, I?¦ll attempt to get the cling of it!

Lovely site! I am loving it!! Will come back again. I am bookmarking your feeds also