1. Market Entry According to the Product Life-Cycle Phase

The international product life-cycle theory developed by Vernon was introduced in 1966 (Vernon 1966). Based on panel research of enterprises from the United States of America, Vernon’s product life-cycle explanations further developed the existing trade theories introduced by Heckscher-Ohlin and Leontief (Vernon 1972). Vernon assumed that the flow of information across national borders would be restricted and that products undergo predictable changes that have an impact on the firm’s internationalization strategies. The product lifecycle model was developed on these assumptions: the production process is characterized by economies of scale, the cycle changes over time, and tastes differ in diverse countries (i.e., each product does not account for a fixed proportion of expenditure for buyers at different income levels). Because information does not flow freely across national boundaries, three important conclusions follow.

- innovation of new products and processes is more likely to occur near a market where there is a strong demand for them than in a country with little demand.

- An entrepreneur is more likely to supply risk capital for the production of a new product if demand is likely to exist in his home market than if he has to turn to a foreign market.

- A producer located close to a market has a lower cost in transferring market knowledge into product design changes than one located far from the market (Vernon 1972).

The international product life-cycle theory claims that the market entry of a product is carried out in a foreign market depending on the position of the product in its country-specific product life-cycle curve. In the 1950s and 1960s, United States products led in the worldwide markets in many industries, while Europe and Japan required time to build up their own industries and infrastructures after World War II. Consequently, Vernon assumed that the United States served as a truly innovative market with customers with high purchasing power compared to other countries.

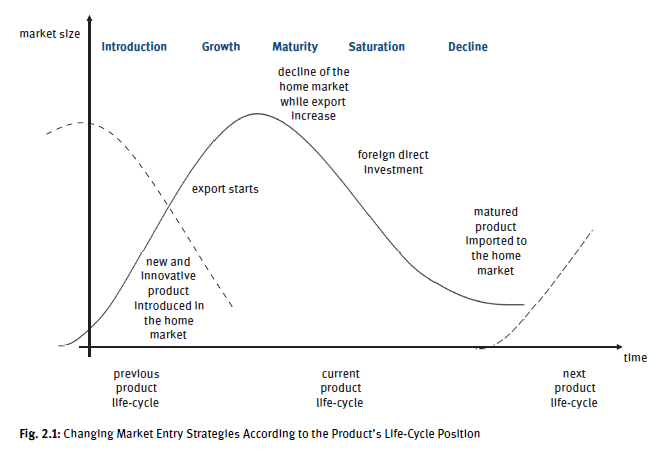

As illustrated in Figure 2.1, Vernon claimed that, for a certain time period, producers based in the US are likely to have a virtual monopoly on the manufacturing of new products introduced in the US An innovative product at its growth phase is produced inland and sold at relatively high prices. The output volume increases in the course of the market penetration inland, and experience curve effects appear. Due to the product’s attractive market growth forecasts, the number of enterprises that produce this product increases in the home country. As a result, standardization and product cost aspects become important in connection with the necessity for mass production outputs. At later stages in the growth phase of the product life-cycle, some foreigners start to demand the new and innovative product; and US exports begin (Vernon 1972).

While the growth rates decline during the maturity stage of the product life-cycle in the US home market, export activities to other countries increase. As foreigners’ incomes grow and lower income consumers abroad begin to buy the mature product, prices begin to fall, while, in parallel, US exports further increase. As the product sales continue and market volumes increase in foreign markets, it becomes economically desirable for US firms to establish foreign production. The time it takes until foreign production begins is dependent on the economies of scale, tariffs, transportation costs, income elasticity of demand, and the income level and size of the foreign market. At the end of the product life-cycle, manufacturing and sales in the US market become more and more unimportant. As a result, local manufacturing runs out due to the relatively high production costs in comparison to foreign countries. The remaining market volume during the decline phase of the product life-cycle is completely imported from abroad, while, at the same time, US firms introduce new and highly innovative products that launch the next product life-cycle (Vernon 1972).

2. Review of Vernon’s Model

To sum up, a firm’s market entry activities depend on the product’s position in the corresponding life-cycle. At first, the new innovative product is developed, produced, and sold in the US home market. In the second phase, product exports start; and while the product becomes mature, direct investments abroad begin. Finally, import from abroad increases, production is discontinued in the home market, and the demand is completely supplied by foreign countries. At this stage, the product has reached the decline phase of its lifecycle.

Vernon’s approach has made an essential contribution to the internationalization concept disciplines. The product life-cycle model provides a useful framework for explaining the post-World War II expansion of US manufacturing and investment activities. However, its explanatory power has waned with changes in the international environment (Robock & Simmonds 1989). Holding an innovative market leadership position does not necessarily last. For example, Japanese consumer electronics firms such as Sony started to replace previously leading consumer electronics firms in the US during the 1960s. At the beginning of the 21st century, Japanese consumer electronics firms suffer from competition from South Korean, Chinese, and Taiwanese firms, which took market share from the Japanese in various fields.

The model can be criticized in general because it assumes an ideal product life-cycle with coherent foreign activities. The theory is limited by the assumption that there is an attractive US home market from which US firms start their global activities. This model assumption is, from the 1960s perspective, substantiated for many industries where the US was ahead of Europe and Japan. It is true that large home markets provide the best prerequisites for experience curve effects and economies of scale. However, the general model validity is hard to test empirically due to the complexity of the product life-cycle. Industry-specific factors, such as tariff and non-tariff trade barriers, behavior preferences of the management, and investment incentives that significantly influence manufacturing costs, as well as cross-border trade and capital flows are not considered in the model (Luostarinen 1980). Vernon’s model is focused on manufacturing industries rather than on services industries.

Today, due to globalized trade patterns and intensified competition, technology and product life-cycles are shorter, while, in parallel, investments in R&D, operations and marketing, and so forth are increasing. Consequently, firms are often under pressure to sell their products globally – right from the beginning of the product life-cycle – in order to realize early economies of scale effects. Moreover, multinational firms often maintain different market entry concepts, such as export and foreign direct investment, in parallel. Nowadays, the customers’ purchasing power does not differ significantly in many industrially developed countries. (Vernon correctly assumed a US consumer’s higher purchasing power relative to the rest of the world in the 1950s and 1960s.) Moreover, customers’ expectations concerning the technical and quality performance of a product and service have become similar in many countries worldwide. As a result, the segmentation of the product life-cycle phases and corresponding conclusions for local sales, export, foreign direct investment, and import, according to the model, is rather arbitrary (Tesch 1980).

As a result of increased global business dynamics in recent years, there are cases of innovative firms that were unknown a couple of years ago. Meanwhile, some of these firms are playing a significant role in the international market (e.g., Huawei from China). Interestingly, taking the case of the online-based business concept of the Chinese Alibaba.com, we can deduce some minor similarities with Vernon’s approach. Alibaba’s global success at the beginning of the 21st century is based, among other reasons, on its quasi-monopoly positioning in its huge Chinese home market. Alibaba currently takes advantage of economies of scale and experience curve effects in China similar to those Vernon indicated as an advantage for US manufacturing industries in the post-war period.

Around a decade after its first publication in 1979, Vernon retracted the life-cycle model and agreed that there were fewer differences among countries in factor costs and market conditions (Barkema, Bell, & Pennings 1996). From today’s view, after decades of major economic and political progress in world trade, the international product life-cycle theory has lost much of its validity. Consequently, further internationalization models have been developed, which are described in the following sections of this chapter.

Source: Glowik Mario (2020), Market entry strategies: Internationalization theories, concepts and cases, De Gruyter Oldenbourg; 3rd edition.

I have learn some good stuff here. Definitely price bookmarking for revisiting. I surprise how a lot attempt you put to make this kind of excellent informative site.