1. Samsung Management Philosophy – History and Today

The Korean economy is characterized by local-market-dominating Chaebols with highly centralized decision structures that consist of many affiliated companies. Compared to large Japanese conglomerates (Keiretsu), Chaebols are generally much younger. The oldest, Samsung, was established in Taegu in 1938 (Chen 2004) by Byung-Chull Lee (Samsung 2007). Unlike Chaebols such as LG Electronics, which was founded in 1947, Samsung’s origin goes back to the period of Japanese occupation of the Korean peninsula.

Confucian heritage is still readily visible in South Korea; and the influence of Confucian values on management is significant, which is particularly the case for the most conservative and powerful conglomerate Samsung. Although Buddhism has generally been accepted as a religion in South Korea and has become an integral part of the lives of Koreans, there is a major difference between Buddhism and Confucianism: Buddhism is understood and practiced as pure religion; and it recognizes heaven, hell, and transmigration. It teaches that anyone can enjoy the life of heaven if he or she lives a virtuous and honest life in this world. Heaven is the reward for what a person has done on earth. In comparison, Confucianism, as originally observed in China, is understood more as a philosophy with moral teachings than as a religion. It is involved in the world, rather than emphasizing the afterlife (Chang & Chang 1994).

The five cardinal values of Confucianism: filial piety and respect, the submission of wife to husband, strict seniority in social order, mutual trust in human relations, and absolute loyalty to the ruler still permeate the Korean society. Nevertheless, today, particularly among the younger and urban population, traditional Confucian ethics, such as family or the collectively oriented values of the East, have mixed with the pragmatic and economic goal-oriented values of the West. Behavior based on Confucianism has changed for reasons that include the influence of Christianity, which came to Korea in 1884 (today Catholics represent around one third of the population), and, to some extent, because of the US presence since the Korean Civil War. Traditional hierarchical roles have changed. Today, scholars and civil servants are at the top; farmers, second; artisans, third; and merchants, last, which has made it possible for businessmen and engineers to prosper in the new industrial society (compare: Kim 1997; Tu 1984).

In Korea, as in most of the other Asian countries, education is greatly emphasized. For this reason, Korean parents sacrifice their lives for the education of their children. The clan plays an important role in social and economic relations. It is not uncommon for a core of Korean firms to be staffed by family members, distant relatives, people from the hometown, or graduates of the same university; and it is not unusual for firms to be managed like quasi-family units (Kim 1997). Harmonious interpersonal consensus-based relations are emphasized. Interpersonal relationships are defined in terms of social status, such as gender, age, and position in the society. Social etiquette is well defined when it comes to interactions among people. Harmony, which refers to respect for other people and a comfortable atmosphere, plays a very important role in Korea, where people try to avoid or minimize face-to-face conflicts. Harmonious interpersonal relationships are mainly built on seniority. Harmony is reached through cultivation and adaptation of one’s self (Rowley, Sohn, & Bae 2002).

The emphasis on personal loyalty to those of higher rank is of vital importance – for example, when working at Samsung. A supervisor can practice massive criticism of a subordinate, while the other way around, unconditional loyalty, obedience, and untiring deployment of labor are expected. This is in accordance with the strict discipline already practiced first at school and later at work as well as in the entire social life. Discipline combined with loyalty, moral obligation, severity, and benevolence contribute to business competitiveness (Chen 2004). It is of vital importance that these attitudes, which reflect the company culture, are respected and shown by each Samsung employee in daily life at work. Samsung staff members do not argue in front of their boss and, instead, are ‘action-oriented’ and busy (in order to realize the boss’s order). Despite the challenges and mental pressure at work, Koreans have a positive attitude towards the future that favors realizing the permanently increasing business goals launched by the Samsung management (Kim 1997).

The Korean culture is fundamentally influenced to a greater degree by historical and philosophical Chinese thought than, for example, is the case in Japan. The philosophical values of old Chinese military strategists were transferred to the business community. The Chinese expression ‘Shang Chang Ru Zhan Chang’ is translated to mean ‘the marketplace is a battlefield’ (Chen 2004). Several Asian business leaders have attached great importance to classical Chinese military strategies. Many of the principles behind these strategies are commonly applied to business activities, of which Samsung serves as example.

According to the idea of paternalistic leadership, Chaebols are controlled by their founders or owners (Samsung: Chairman Lee Kun-Hee) and their families, who usually have enormous influence not only on the organizational culture but also on business strategies. In business, decision processes, and strategies, the Samsung management is target and goal oriented. Consequently, the company pursues a permanent trade-off between the regional advantages and weaknesses at plant locations around the globe. The management of the Samsung headquarters (located in Seoul) is free to intervene in any subsidiary at any time. According to Rowley et al., military structure contributes heavily to ideas about how business organizations should be designed and operated. This orientation influences behavior, predisposing companies to emphasize hierarchical command, a result-oriented ‘can-do spirit,’ and competition among the employees (Rowley et al. 2002). The hierarchical work atmosphere at Samsung was described by one Samsung employee as follows:

There are a lot of unscheduled and sudden orders with an urgent due date from the top management and CEO. Even if managers do make a false decision or mistake or give inappropriate orders, employees do not reject it or speak out loud to say it is wrong. Koreans are quite used to being told and directed by managers (or teachers) about what they should do ever since they were teenagers at school and, therefore, very often have a lack of creativity and are afraid of trying new things and breaking rules (Glowik 2007).

Koreans rely heavily on personal relationship networks that are embedded in blood relations, growing up in the same region, a similar academic background, or the university attended. According to an empirical study by Chang and Chang (1994), Koreans have most confidence in members of their own family, followed by high school classmates and people from the same region. In contrast, Koreans do not trust Korean strangers and foreign people. Due to their long history as a relatively homogeneous ethnic group, Koreans have a high level of communication based on shared contexts (high-context society). They like to convey information through nonverbal cues embedded in physical settings or internalized in particular personal relationships (Rowley et al. 2002).

The Western scientist Hofstede (2001) describes Korea as one of the most collectivist countries in the world. However, Asian scholars like L. Kim (1997) indicate that Koreans are more individualistic than, for example, Japanese (Chang & Chang 1994). Western expatriates of multinational companies often presume collective attitudes in Korean managers but recognize individualistic, even egotistical, forms of behavior. Koreans have a strong tendency to distinguish themselves from others and show collectivist behavior only to people in the ‘in-group.’ Among Koreans, communication is more personalized and smoothly synchronized, which is the opposite in the case of communication with ‘out-group’ members (Rowley et al. 2002).

From the Korean point of view, the success or failure of business reflects one’s ‘own face’ and directly influences the survival of the private family and, consequently, the prosperity of the whole nation (Chen, 2004). According to Kim and Bae (2004), compared with Western enterprises, Korean firms give more weight to human nature – for example, personality, behavior and company-culture integration – than the purely job-related competence of an employee – for example, performance, achievements, and expertise (Kim and Bae 2004). This attitude differs from Western cultures, where company performance (expressed rationally in profit or loss figures) and private life are perceived as separate matters. Koreans see the company’s prosperity as a private matter and, consequently, view it more emotionally. In the case of Samsung, this is reflected in the strong motivation of the employees. As one Samsung staff member commented to me during an interview in Seoul:

A task or project is to be done by a due date; all team members are devoted to completing the job as fast as possible by dividing the work. The strengths of Asian-based companies are personal relationships and networks, team-work, and selfsacrifice. In Europe, work and personal life are completely separate and isolated. After work, employees do not go together for a further casual discussion. Work time is very rigid and inflexible. At 06:00 p.m., no one is present at work because they have gone home. Europeans have long vacations.

‘The person in charge is on holiday for three weeks; therefore, the job cannot be done at the moment. Please wait.’ When a Korean business partner listens to such information on the phone and is confronted with such a situation, he or she is speechless. Speed is the key in the twenty-first century, especially in high-technology industries such as the electronics business (Glowik 2007).

If the profit of a business segment tends to drop, countermeasures follow from the Samsung management immediately. These activities contain restructuring programs, reduction of employees, and the shut-down of production lines or whole plant facilities as was the case in Wynyard, Great Britain, in 1998; Berlin, Germany, in 2006; Tschernitz, Germany, in 2007; and Goed, Hungary, in 2013 (Samsung 2014a; Zschiedrich & Glowik 2005). As the company slimmed down during the financial crisis in Asia from about 1997 to 1999, around 30 percent of the employees lost their jobs (Genser 2005). In the spring of 1998, approximately fifty middle-level managers in the manufacturing plant in Busan (South Korea) took ‘early retirement,’ which can be regarded as a de facto layoff program (D.-O. Kim & Bae 2004). The financial crisis in Asia caused the number of regular production workers in the Busan plant to be decreased from approximately 7,000 to 5,000. Wages were cut by around 10 percent, and benefits like summer vacation allowances were abolished or temporarily restricted. At the end of 2006, several managers at the plasma television set business division in Korea had to leave the company due to a sales performance that was lower than expected by the top management (Kim & Bae 2004).

Restructuring activities like those described above more closely resemble US conditions than traditional Asian management behavior. The influence of the US after World War II – for example, liberalization from Japanese occupation, military support of South Korea during and after the Civil War (1950-1953), and considerable financial aid – have obviously made the country open to Western management styles. Korea’s business elite has a preference for Western ways of thinking, which has encouraged learning from industrialized countries along with imitation of advanced technology and management. This is connected to traditional behavioral values like positive attitudes towards hard work and lifelong learning, which have contributed to the successful performance of Samsung. Employment fluctuation, for example, is comparatively much lower at Samsung than in most US-based enterprises (rather short-term oriented) or in Chinese firms (rapid economic growth). Compared to Japan, the human resource management practice at Samsung could, therefore, be described as a ‘semi-lifelong’ employment policy (Chen 2004).

Unlike its biggest rival, LG Electronics, Samsung is a non-union company. The non-union philosophy was influenced by the founder of Samsung, Lee Byung Chul (Kim & Bae 2004). Representatives of German trade unions reproached Samsung for selecting production locations based on the volume of subsidies. For instance, after subsidies by the local Berlin government expired in March 2006, production at Samsung SDI Germany was shut down; and 700 employees were dismissed. Samsung SDI Hungary, established in 2002, took over production from Germany. The Hungarian government supported the investment with considerable tax incentives. A couple of years later, the Hungarian plant was shut down and transferred to Slovakia due to lower labor costs (Jacobs 2006; Wohllaib 2006). However, a couple of years later in 2018, Samsung’s assembly factory in Slovakia (Voderady) was shut down. Samsung also manufactures displays in Galanta (Slovakia). ‘The company lacks production workers adding that the Voderady plant has no longer received any state subsidies, so the South-Korean consumer electronics producer has no problem with shutting it down,’ as communicated in Slovakian mass media (Slovak Spectator 2018).

Nevertheless, Western electronics firms do not differ very much in that way. For example, the Finnish Nokia in 2008 closed its mobile phone manufacturing in Bochum, Germany, and transferred it to Rumania, where considerable subsidies were paid. And there is another historical aspect to consider. After the Korean Civil War, Korean Chaebols such as Samsung, LG Electronics, Daewoo, and Hyundai grew successfully because of the fundamental financial support of the South Korean government, among other reasons. Thus, deciding on investment activities based on the size of tax incentives is neither immoral nor exceptional for Korean managers, especially not at Samsung.

2. Conglomerate Diversification of Samsung Group

A corporate strategy mirrors organizational processes that are inseparable from the structure, behavior, and culture of the company (Andrews 2003). Company growth in industries unrelated to the current business through conglomerate diversification strategies is a significant characteristic of all Korean Chaebols. Historically, diversification strategies have been widely advocated and supported by the Korean government. Samsung entered into wood textiles and sugar in the 1950s; fertilizer and paper production started in the 1960s; construction, electronic components, heavy industry, petrochemicals, and shipbuilding were entered in the 1970s; and aircrafts, bioengineering, and semiconductors were introduced in the 1980s (Chen 2004).

Japanese companies made an essential contribution to the construction and development of Samsung. In 1969, a joint venture with Sanyo (Japan) was agreed upon, which later led to the founding of Samsung Electro-Mechanics. Samsung Display Devices is the result of a joint venture with Nippon Electric Company (NEC), Japan, which was established in the same year. The foundation (1969) and development of Samsung Electronics, nowadays one of the most important business divisions of Samsung Group, was supported by Japanese companies that were involved by contributing essential technology and management know-how transfer. As a result, the first black-and-white television set was produced in 1971 by Samsung (Samsung 2007). The international joint venture, Samsung Corning Precision Materials, which is a manufacturer of high-quality glass parts for the production of displays, resulted from an agreement between Corning Inc., USA (e.g., assembler of today’s well-known ‘Gorilla glass’) and Samsung in 1973. Major production capacities for the glass used in smartphones and television sets are located in South Korea, China, and Taiwan. As a result of the joint venture, Samsung Display will secure LCD screen glass supplies from Corning, Inc. until 2023. Corning, Inc. has majority ownership in the joint venture (Corning 2013). The international joint venture between Corning, Inc. and Samsung has been developed over decades and serves as one of the rather rare existing examples of successful and long-term Western-Asian international joint ventures.

Samsung’s continued relationship-seeking efforts brought it into collaborative arrangements with the world’s technologically leading firms. For example, in 1994, it was announced that Samsung and the Japanese NEC would share development efforts at a cost in excess of USD one billion to bring a 256 M DRAM to market in the late 1990s (Lynskey & Yonekura 2002). In 2001, Samsung and NEC agreed upon a new joint venture called Samsung NEC Mobile Display OLED. The main target of the joint venture was to join efforts to develop the OLED business. Samsung and NEC can rely on their long-term experience in running joint ventures, which has been developed for decades. Over time, various additional technological alliances have helped develop Samsung into one of the leading firms in consumer electronics. Samsung’s top management has continuously searched for new market potentials for the future and strengthened its efforts to establish selected alliances, such as with Nokia (2007, mobile phone technologies), Limo (2006, Linux-Platform), IBM (2006, industrial print solutions), and Bang and Olufsen (2004, home cinema systems), just to mention some of the actors in Samsung’s business network (Samsung 2008b).

Since the 1990s, the competition between South Korea and Japan in the field of electronics has become intense. Although South Korea’s electronics industry, which grew by introducing Japanese technologies, was behind that of Japan in the initial phase, South Korean companies, with Samsung as a representative, made innovations on the basis of digestion and assimilation. For example, in 2004, Samsung and Sony decided to establish the joint venture S-LCD Corporation and shared the output from the ‘seventh-generation’ LCD factory (Genser 2005). At this time, Samsung was technologically already ahead of Sony in flat panel production. Samsung’s newly gained position as a serious rival was one of the major reasons that Sony did not prolong the joint venture with Samsung and, instead, started to collaborate intensively with Sharp in the LCD panel television set business (Otani, 2008). As a result, Samsung acquired all of Sony’s shares of S-LCD Corporation in 2011, making S-LCD a wholly owned subsidiary of Samsung. Meanwhile, in terms of capacity and technology, Samsung successfully exceeded several Japanese firms in the fields of display panels, smartphones, and semiconductor production (Kim 1997; Samsung 2018). As of 2018/2019 Samsung held a global market share of around 28 percent in TV sales. In 2018, global TV demand increased 2.9 percent compared to the previous year, reaching 221 million units (Samsung 2018).

Samsung has accelerated its relationship efforts with other firms doing business in promising future markets, such as connected electric cars, healthcare and medical devices. For example, in 2008, Samsung established an international joint venture called SB LiMotive Co. Ltd. with the German Robert Bosch GmbH for the development, production, and sales of lithium-ion battery systems. Robert Bosch GmbH and Samsung SDI each invested 50 percent in that international equity joint venture. The management and the supervisory board consisted of an equal number of appointed members from both enterprises (Samsung 2008a, 2008b). The knowledge developed and acquired from the joint venture of Bosch and Samsung is applicable for batteries used in electronics devices and cars. However, in 2012, Bosch withdrew its stake in the joint venture due to ‘strategic differences’ with its joint venture partner (Hammerschmidt 2012). Probably, Bosch became aware of the risk that Samsung would gain car battery as well as electric car management knowledge, which would help Samsung become a powerful competitor to Bosch in the promising future electric car business.

As a consequence of the international joint venture termination with Bosch, Samsung SDI announced the acquisition of the battery pack division of Magna Steyr International in 2015, which further solidifies the company’s foothold in the automotive market. The agreement to buy Magna Steyr includes all machinery, research and development sites. With the acquisition, Samsung is focusing on growing customers in the electrified vehicle markets in North America, Europe, and China. Samsung aims to manufacture complete car dashboards for electric cars and aims to become one of the major global suppliers in the automotive industry. Samsung SDI supplies battery cells to BMW for its i3 and i8 plug-in cars (Gastelu 2015).

Interestingly, and less well known in Western countries, Samsung had already held a foothold in the automotive industry since the end of the 1990s when Samsung agreed with the Japanese company Nissan to build a version of the Maxima, called the SM5, which went on sale in 1998. As a result of the Asian financial crisis, which affected Nissan too, Renault from France acquired around 43 percent share of Nissan and, as a consequence, Renault Samsung Motors was established (Gastelu 2015). In order to further strengthen Samsung’s positioning in the (connected) car industry, the reputable Harman company was acquired in 2017. Harman designs and engineers products for automakers, consumers, and enterprises worldwide, including connected car systems, audio and visual products, enterprise automation solutions, and connected services. With brands including AKG®, Harman Kardon®, Infinity® ,JBL®, Lexicon®, Mark Levinson®, and Revel®, Harman manufactures products for carmakers, audiophiles, musicians and the entertainment venues. Around 25 million automobiles on the road are equipped with Harman audio and connected car systems. Harman software services power billions of mobile devices and systems that are connected, integrated and secure across all platforms, from work and home to car and mobile. Harman has a workforce of approximately 30,000 people across the Americas, Europe, and Asia (Samsung 2019b).

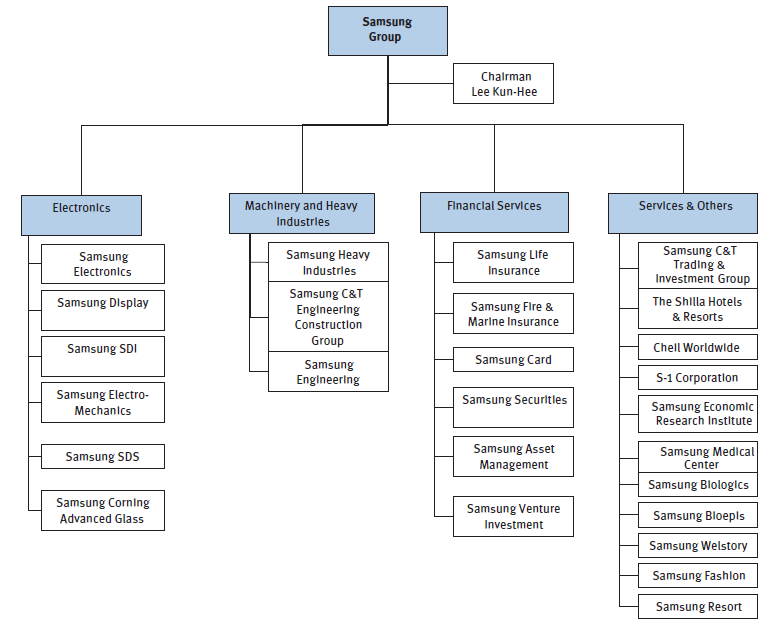

Today (compare Figure 4.20, status: 2019/2020) Samsung group is separated into four main business divisions named electronics (e.g., display, SDI, electro-mechanics), machinery and heavy industries (e.g., engineering and construction), financial services (e.g., insurance and credit card), and services and others (e.g., Shilla, Cheil, trading, healthcare, fashion). As of December 31, 2018, Samsung Group had a total of sixty-two (62) domestic affiliates, with the addition of one (1) affiliate (Samsung Electronics Service CS) and a reduction of two (2) affiliates (S-Printing Solution and Daejung Offshore Wind Power) from December 31, 2017. Among the Samsung Group’s sixty-two (62) domestic affiliates, sixteen (16) affiliates including Samsung Electronics are listed, and forty-six (46) affiliates are unlisted (Samsung 2018).

Fig. 4.20: Diversified Organization of Samsung Group (status: 2019). Source: Samsung (2019b)

Samsung’s strategic advantage in today’s business lies in its highly diversified activities, which allow aggressive market entry and penetration strategies because temporary losses in foreign markets are compensated by a continued flow of revenues in the native country, where the company has a dominant position. Although the financial, legal, and organizational encouragement by the Korean government to strengthen the Korean Chaebols is lower nowadays than in earlier decades, Chaebols still have several advantages due to their size and importance for the country’s economy. Samsung has a quasi-monopoly position in many areas. For instance, there is the luxury Hotel Shilla in the capital of Seoul. Samsung Everland, a large entertainment and amusement park, follows the US example of Walt Disney (Samsung 2019b). Samsung is not only extremely diversified but their businesses also indicate vertically integrated value chain activities through even nonfamiliar industries.

As Figure 4.21 illustrates, for example the business unit of Samsung Engineering and Heavy Industries constructs plant facilities for manufacturing products by Samsung SDS and Samsung Electronics and Samsung Medical centers. Samsung Economic Research Institute delivers valuable industry and market information to all other business units within Samsung Group. Samsung Financial Services provides the financial backup for investments. Samsung Trading and Investment takes care for the customer relationship management and it responsible for all businesses of Samsung. Research results generated at Samsung Biologics (downstream) are used at Samsung Medical centers (upstream). These examples give only a little insight into the well-developed “internalized businesses” flows within Samsung’s largely diversified operations.

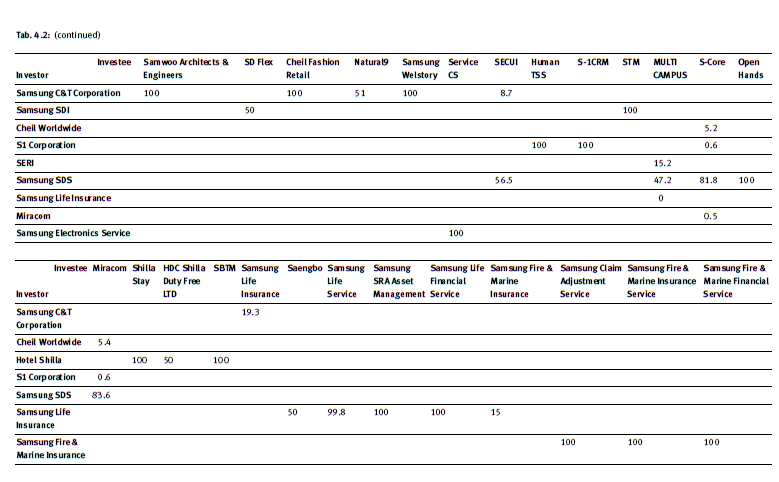

Another characteristic of Korean Chaebols is its very fine-grained mutual shareholder participation of the diversified business units, and the Samsung Group serves as an excellent case. As illustrated in Table 4.2, Samsung Electronics holds the highest shareholder percentages in the other business units, which underlines its important role for Samsung Group. Due to its strategic importance, if the electronics business suffers, the entire Samsung organization may start swinging. The proportion of Samsung Electronics ownership by ‘special relations’ of the ruling Lee family, including Vice Chairman Lee Jae-Yong has increased in recent years. At the end of 2018, Samsung Group chairman Lee Kun-Hee owned 3.88 percent of Samsung Electronics, while Lee Jae-Yong owned 0.65 percent (Lee 2018; Samsung 2018). Therefore, the Lee clan is able to control Samsung Electronics because of the circular equity structure within Samsung Group, such as Samsung Everland, Samsung C&T, and Samsung Insurance. The total shares in these companies held by Lee and his family are worth a minimum of 10 billion euros. Lee and his family exercise absolute management authority (Han, Liem, & Lee 2013).

Samsung realizes various advantages accruing from diversified product lines. One obvious benefit is the resulting diversified business risk. Because the company’s products spread out into many fields, it is more effectively able to cope with the ups and downs in particular product markets; and this helps the company to develop its sales performance, which reflects the company’s growth strategy in the global markets. Another advantage is the cross-product component sharing, which is important when different products are converging onto the same platforms (Chen & Li 2007). Large manufacturing facilitates help spread the costs of research and development and allow realization of overall economies of scale effects.

Successful growth provides the chance to take advantage of the experience curve in order to reduce the per- unit costs of products sold. The sales development of Samsung Group has shown an outstanding sales performance over the last years relative to its competitors. However – compared to the industry benchmark in terms of profit margins, for example Apple Inc. (USA) – Samsung’s management has not been able to expand net income with the same growth rates. What might be the reason for this shortfall? First, Samsung is embedded in various and diversified business fields and owns facilities that have enormous fixed costs. Thus, taking the risk of running overcapacities, the firm becomes vulnerable in the case of economic downturns in the worldwide markets. In this situation, Samsung often sells its products at relatively marginal price levels in order ‘to feed their production lines.’ Second, the electronics industry, which is the core business of Samsung Group, is highly price competitive. Permanent product innovations are necessary to secure the firm’s business destiny for the future.

There is no doubt – relative to its Japanese rivals, such as Sony, Sharp, and Panasonic – that Samsung has reached a more stable and prospective business performance during the last years. Samsung has concentrated on its core competence, the electronics business. The firm invested early in LCD/LED displays and smartphone production capacities at a time when the market potential was neglected by others. In addition, Samsung Electronics has been expanded in several vertically integrated business segments. Therefore, Samsung’s vertical integration is described in more detail in the following section.

3. The Strategy of Vertical Integration of Samsung Electronics

The most important business division within Samsung Group is Samsung Electronics. Headquartered in Seoul, South Korea, Samsung operates 252 subsidiaries globally, including nine regional headquarters for the Consumer Electronics and Information and Mobile Divisions, five regional headquarters for the Device Solution Division, and in addition the recently acquired Harman’s subsidiaries (Samsung 2019b). A summary of Samsung Electronics product range (status: 2019/2020), divided into its four major strategic business units, is illustrated in Table 4.3.

The strength of Samsung Electronics is the company’s efficient use of its worldwide vertically integrated research and development, procurement, manufacturing, and sales network. Vertical integration means a firm utilizes an internal transfer within the organization of intermediate parts that a firm produces for its own use, such as materials, components, semi- or completely assembled products, and services. A firm may integrate backward and start generating value-added activities it previously procured from outside suppliers. Alternatively, a firm may integrate forward and start integrating products and services, such as a sales and distribution or after-sales service, in order to be closer to the firm’s customers and their ‘voices.’ Both of these processes represent methods of a firm’s growth strategy (Penrose 1995:145).

After the Korean Civil War, during the second half of the 1950s, the Korean government started to route Chaebols into particular industries without building the infrastructure of component suppliers or supporting services. Since the Chaebols found it difficult to purchase or otherwise secure the necessary materials and components and the Korean government pushed domestic firms to industrialize, there were clear and seemingly inevitable reasons to integrate, thus internalize value-added activities, vertically. Differences in the Chaebols’ use of vertical integration stem from the distinct characteristics of the industries with which the conglomerates are involved (Chang 2003). For example, in the case of smartphones and television sets, Samsung Electronics controls almost all stages from research and development, to manufacturing, up to worldwide sales and distribution. In comparison to Western consumer electronics and information technology enterprises such as Philips or Apple, the Korean firm indicates a much deeper grade of vertical integration.

Figure 4.23 illustrates the vertical integration strategy of Samsung Electronics which is applied as follows in the case of its Galaxy smartphones and its television sets: on the downstream side Samsung SDS provides the information and communication technology infrastructure. Samsung Display manufactures and supplies LCD and OLED displays for television sets and smartphones. Samsung Display relies on Samsung Corning, which produces the screen glass for the displays. Moving on the value-adding chain towards upstream activities, Samsung Electro-Mechanics delivers electronic components for the display and television set, audio and smartphone product assembly. The final manufacturing and sales of smartphones and television sets is done by Samsung Electronics. Complete vertical integration helps Samsung maintaining better quality control and secures delivery punctuality than the company could achieve through external market transaction. Furthermore, vertical integration means that the fruits of research and development in one stage of production are more likely to be shared with other stages, thereby increasing the overall competitiveness of both upstream and downstream operations. Through its vertical integration, Samsung Electronics is able to launch its products more rapidly on the global markets than most of its competitors (Chang 2003; Kim 1997; Worstall 2013).

Samsung Electronics performs well in terms of net sales and net income and is much better positioned, considering the last decade, than most of its Japanese competitors. Comparing 1997 with 2018, turnover and profits have increased considerably (compare Figure 4.24). Nevertheless, vertical integration also comes along with potential challenges. One of the potential hazards to efficiency comes from vertically integrated suppliers who sometimes lack the incentive to be more efficient or innovative because they have captive in-house customers (Mahoney 1992). This lack of incentive can be severe in the case of Chaebol affiliates because large portions of their sales are transferred internally (Chang 2003). In-house component production may be less efficient relative to its procurement from outside supply sources (Roberto 2009).

In the worst case, financially troubled affiliates can survive only with support from their parent company, which guarantees production volumes, at least for a certain period of time. The internal charges between the company units are sometimes (but not necessarily) at higher prices than the market average. To create a homogeneous group culture and facilitate the inter-group transfer of personnel, Chaebols use the same level of benefits for all business units, which are sometimes generous for poorly performing businesses. They often support unprofitable affiliates via various forms of internal transactions (Chang 2003). The permanent challenge for Chaebols like Samsung is favoritism, which leads to buying from within Chaebol and hinders competition as well as the input of fresh, innovative business ideas from group outsiders. The top management of Samsung recognized this danger and started to run each business unit as a separate profit center, which supports competition with outside suppliers for orders up to a certain budget. In some cases, up to one third and more of product demand is procured from Samsung’s outside sources, even if it could be supplied in-house.

The system of component production and supply for Samsung Electronics is made up of five layers. The first layer is composed of Samsung Group subsidiaries and accounts for around ten percent of the value of the components purchased by Samsung Electronics. The second layer is made up of transnational electronics component suppliers who have independent technical capability. The US-based Qualcomm, which has a CDMA patent, and 3Com, which has a wireless patent, are examples of companies in this layer. The third layer comprises suppliers to which Samsung Electronics outsources parts production that it could produce by itself but chooses not to do for cost or production capacity reasons. Third layer companies are, for example, the Taiwanese AU Optronics which supplies small-scale LCD panels. The fourth layer is composed of domestic subcontractors that supply parts that Samsung Electronics could not produce itself, for example mobile phone cases manufactured by Intops LED Company Ltd. The final layer in the supply chain is composed of smaller low-cost parts (Han et al. 2013).

Samsung Electronics does not procure and manufacture components only for its in-house uses. It also serves as a vertically integrated, specialized, and large-scale supplier for its major competitors, such as Sony (Dynamic Random Access Memory [DRAM], LCD panels), Apple Inc. (mobile processors, DRAM), Dell (DRAM, flat panels, lithium-ion batteries), and Hewlett-Packard (DRAM, flat panels, lithium-ion batteries). Having control over these components has major implications both for performance and reliability. Samsung has knowledge of various nuances of these components and can tweak them along each step in the development process to ensure that they work together perfectly. Manufacturers of solid state drive (SSD) controllers have to worry about supporting multiple specifications (from varying manufacturers who each have different manufacturing processes), while Samsung’s proprietary SSD controller is engineered solely to work with its own components – which means engineers can focus all of their efforts towards one common specification. As the most integrated SSD manufacturer in the industry, Samsung controls all of the most crucial design elements of an SSD: NAND, Controller, DRAM, and Firmware. Working together, these components are responsible for a crucial task – storing, stable operating, and protecting precious data (Samsung 2014b). From 2019/2020 onwards Samsung aims to offer power-efficient and slimmer products to capture demand for the emerging 5G mobile communications standard and 8K TVs as well as high-end monitors (Samsung 2019c).

In contrast to Samsung, Apple Inc. is a vertically integrated specialized buyer. Apple Inc. represents four companies in one – a hardware company, a software company, a service company, and a retail company. It controls all the critical parts of its value chain, but leaves the manufacturing process of its electronics components to other companies, such as Samsung. Consequently, Apple Inc. is rather a design company, not a manufacturing company like Samsung Electronics (Vergara 2012). Samsung’s supplier positioning also poses another risk. The firm finds itself competing with its customers – which are, in parallel, competitors. About a third of Samsung’s revenue comes from companies that compete with it in producing television sets, smartphones, computers, printers, and other items (Ramstad 2009).

4. International Business Expansion

As South Korean electronics firms gradually strengthened their presence and expanded their market shares overseas, import restrictions regarding goods from Korea increased in key markets such as the United States and the European Union. By the end of the 1980s, there were restrictions in the form of antidumping duties, quotas, and quality standard restraints on Korea’s major export producers of television sets, including Samsung. (Cherry 2001). As a result, Korean Chaebols strengthened their foreign direct investment activities, and overseas expansion through foreign direct investment has been impressive in the case of Samsung Electronics.

During the 1970s, the firm concentrated its manufacturing capacities on its home market, South Korea. The first foreign direct investment outside Korea was done in Mexico and Thailand (1988). In Europe, Samsung built its first television set manufacturing plant in Hungary in 1989. At the beginning of the 1990s, Samsung Electronics established several manufacturing locations for a wide range of products (e.g., television sets, audio, telecommunications, etc.) in China. An abstract of the manufacturing capacity expansion of Samsung Electronics, as well as the year of establishment and manufactured products, is illustrated below for the period 1969 to 2016.

In 2002, taking advantage of a favorable investment environment (e.g., relatively low costs combined with subsidies from the government), Slovakia was selected as a new investment location for building television set manufacturing capacities in Europe. In 2008 and 2009, Samsung invested in Russia and Poland, while ‘coming back to Asia’ when it established LCD (2012) and semiconductor (2013) manufacturing capacities in China and telecommunications and consumer electronics manufacturing (2013) in Vietnam (Samsung 2018).

The international business expansion of Samsung, however, is not without drawbacks due to fast changing global competitive forces as Samsung experienced to their regret in China. In 2019, Samsung’s market share in the Chinese market shrank to one percent in the first quarter compared to around fifteen percent in 2013 – mainly due to aggressively emerging Chinese brands such as Huawei Technologies and Xiaomi Corp (Park, Fernandez, & Evans 2019). The shutdown of Samsung’s last Chinese phone factory as of the end of 2019 came after production cuts at its plant in the southern city of Huizhou in June 2019 which underscores the intense competition in China. ‘In China, people buy low-priced smartphones from domestic brands and high-end phones from Apple or Huawei. Samsung has little hope there to revive its share,’ said Park Sung-Soon, an analyst at Cape Investment & Securities (Park et al. 2019).

On the one hand, straight from its foundation, the Samsung management has invested in various worldwide locations where it has forecasted promising business opportunities – instead of paying too much attention to geographical distance or perceived cultural differences. On the other hand, taking the recent case of its smartphone sales in China, Samsung’s management does not hesitate to launch retrenchment and divestment strategies. Traditional internationalization theories like the Uppsala approach assume that firms follow a linear, forward-directed incremental internationalization chain pattern (Johanson & Vahlne 1977; Luostari- nen 1980). Interestingly, Samsung has developed its international business, from its beginning already in the 1980s, in contrast to the traditional internationalization theories. As can be seen, in the business expansion route of Samsung Electronics, the firm did not follow an incremental, linear investment path from nearby countries located in Asia to more distant countries such as those overseas. Instead, Samsung invests where the management ‘sees opportunities.’

Samsung Electronics has continuously increased its efforts to seek a reputation as a premium brand manufacturer. In this regard, Samsung’s advertising campaigns have increased considerably. In Europe, Samsung is known for its electronics products, particularly Samsung Galaxy smartphones, monitors and television sets but plays a minor role in other businesses, such as heavy industry, insurance, credit cards, and others. As per end of 2019 Samsung Electronics was operating 14 research and development hubs in 12 countries and, in addition, artificial intelligence branches in Korea, the USA, Canada, the UK, and Russia (Samsung 2019a) (compare Table 4.5). The locations are selected according to regional knowledge and expertise and corresponding availability of educated personnel in the foreign target countries. Market data as well as research and development knowledge gained from abroad is transferred to Seoul, South Korea and bundled at Samsung Research Artificial Intelligence Center (SAIC).

There is no doubt that Samsung has successfully changed its reputation from an original equipment manufacturer (OEM) during the 1980s to a technology- and marketing-driven company today. Samsung’s strength is based on its expertise forecasting future market potentials, which comes along with its major strength: very fast market response times. Despite its diversified business portfolio, further strengths of Samsung lie in its vertical manufacturing depth (compare, for example, smartphone and television set assembly) and in the firm’s fast knowledge absorbing capabilities of strategically valuable information from customers, suppliers, and competitors’ products. The acquired knowledge immediately results in newly developed products and the establishment of vertically integrated economies of scale manufacturing techniques, using regional cost advantages in its own factories – such as those in China and, more recently, in Vietnam. The products are launched through Samsung’s global sales network, usually faster than its competitors, which allows further experience curve and learning effects (compare elements of the internalization theory).

Additionally, through faster market entry than its competitors, an impression of an innovative technological pioneer (first inventor) is spread, which is in most of Samsung products still not the case (e.g., LCD TV was mainly developed by Sharp, mobile phones by Nokia, smartphones by Apple, laptops by Toshiba, Blu-ray by Sony, streaming music by Spotify, and so on). Samsung rather holds the position of the ‘second first,’ targeting to learn from the mistakes of the others; but this is done very effectively by the largest Korean Chaebol. This absorptive capability (compare the resource based view), together with its efficient forecasting and market timing, establishes Samsung as a true industry benchmark in high-technology industries.

Source: Glowik Mario (2020), Market entry strategies: Internationalization theories, concepts and cases, De Gruyter Oldenbourg; 3rd edition.

Very interesting details you have noted, thanks for putting up.