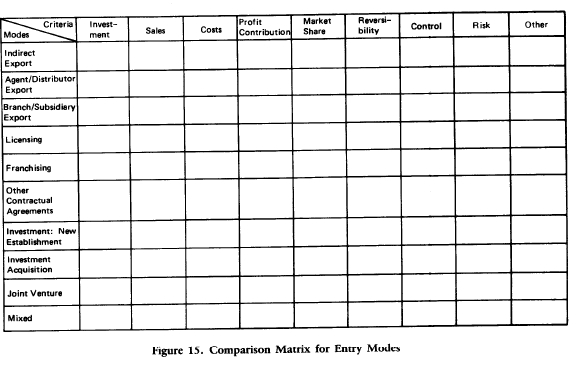

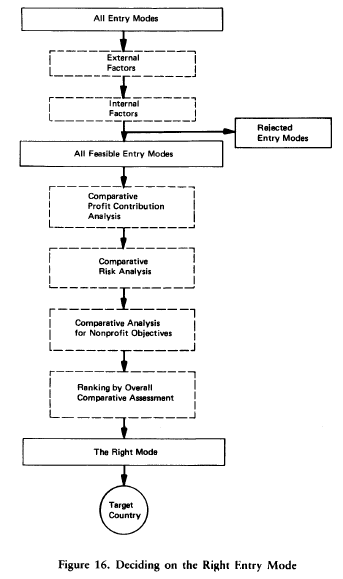

The approach offered here interprets the strategy decision rule as follows: Choose that entry mode that maximizes the profit contribution over the strategic planning period within the constraints imposed by (1) the availability of company resources, (2) risk, and (3) nonprofit objectives. Figure 16 depicts this approach.

Managers start by reviewing all entry modes for feasibility with respect to the foreign target country/market and with respect to the company’s resources and commitment. Is it possible for our company to enter the target market in this way? Feasibility screening is negative screening. Some entry modes may be ruled out for external reasons—for example, export entry may be blocked by import restrictions in the target country. Or they may be ruled out for internal reasons, notable the resource/commitment factor. Ordinarily, feasibility screening can be done quickly, but it should be done on the basis of reliable information.

The feasible entry modes justify a systematic comparative evaluation because they are all within the company’s resource/commitment capability and they are all possible ways to penetrate the target country. Three kinds of comparative analyses are called for: profit contribution, risk, and nonprofit objectives. Managers should then bring the results of these analyses together in an overall comparative assessment that ranks the feasible entry modes. The highest-ranking mode is the right, or most appropriate, mode for the company.

1. Comparative Profit Contribution Analysis

The profit contribution of a foreign market entry mode is the net revenue it will earn for a company over the strategic plan. Estimation of the profit contribution requires that managers project all costs and revenues that will result directly or indirectly from using an entry mode for a target country.’ Different entry modes will have different time profiles for revenues and costs. Export entry, for example, will ordinarily bring quicker returns than investment entry. To standardize time profiles for comparative analysis, it is necessary to calculate the present values of estimated profit contributions over the same number of years.

Profit contribution analysis is identical to the cash flow analysis described in Chapter 5. Its use is justified here by regarding all entry mode decisions as investment decisions. Broadly defined, “investment” includes all once-for-all allocations of a company resource that are intended to generate income over a lengthy future period. Hence startup costs that are incurred to enter a new foreign market (learning about and organizing for a new business environment, hiring personnel with new skills, negotiating with foreign businessmen and host government officials, undertaking market research, adapting the product, developing distribution channels, securing permanent working capital, and so on) are as much part of a company’s “entry investment base” as an investment in a new foreign plant. Although startup expenditures may be charged off against current income as expenses, they are nonetheless investments in an economic sense if their benefits can be realized only over several years.

To estimate the net profit contribution, managers need to identify and measure all revenues and costs that would arise from the use of an entry mode—that is to say, all incremental revenues and costs, whether directly or indirectly resulting from the entry mode. If, for example, an investment entry mode is expected to create net export revenues, then these revenues should be added to the direct revenues of that mode. Conversely, if an investment entry mode is expected to lower current export earnings by displacing exports to the target country, then the forsaken export earnings should be added to the costs of that entry mode. In short, profit contribution analysis boils down to two questions: If we choose this entry mode, what will happen to our revenues? What will happen to our costs?

Summing up, comparative profit contribution analysis requires five steps: (1) Identify/measure/project over the planning horizon (say, five years) all revenues (net of foreign and U.S. taxes) that would be received by the company from the use of each feasible entry mode. (2) Do the same for startup and operating costs. (3) Using projections from the first two steps, calculate the net profit contributions for each year of all the feasible entry modes. (4) Adjust the expected profit contributions for the time value of money by calculating their net present values at the company’s hurdle rate. (5) Rank-order the feasible entry modes by the size of their net present values.

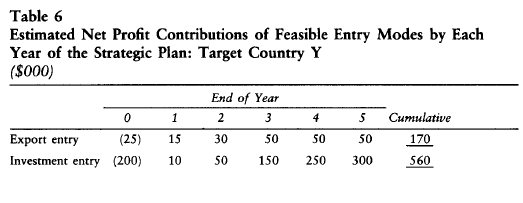

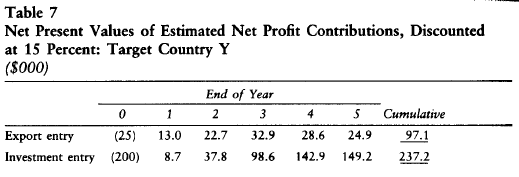

Tables 6 and 7 illustrate a comparative profit contribution analysis in a situation where only two entry modes have passed the feasibility test. This example is simplified, because, as we know, there are several forms of export and investment entry. The planning horizons of the different entry modes can always be made the same by using terminal values, but here we simply assume identical horizons.

It is evident from Table 7 that investment entry offers the highest profit contribution after discounting at the company’s hurdle rate. At this stage of the analysis it therefore becomes the preferred entry mode. This choice rests on our interpretation of the strategy decision rule: choose the feasible entry mode that maximizes profit contribution. This interpretation implicitly assumes that a company can obtain at its hurdle rate all the capital it needs for any entry mode. If this is not the case and managers need to ration capital, they may prefer to rank entry modes by their rates of return on investment. One way to do this is to calculate the cumulated net present value per dollar of investment entry base; another way is to calculate the internal rate of return. In Table 7 the per-dollar profit contribution of export entry is $97.1/25, or $3.9, and that for investment entry is $237.2/ 200, or $1.2. The internal rate of return is also higher for export entry. Managers trying to maximize the rate of return, therefore, would prefer export entry over investment entry.

2. Comparative Risk Analysis

In Chapter 5 we discussed the adjustment of cash flows for political risk. We propose here that the same approach be used, namely, adjusting the yearly profit contributions of each feasible entry mode for both market and political risks.

Generally, political risks are greater for investment entry than for export entry. In most instances, therefore, a comparative risk analysis would lower the cumulative profit contribution (net present value) of investment entry relative to that of export entry. It could even reverse the ranking of the two modes.

3. Comparative Analysis for Nonprofit Objectives

Managers need also to analyze feasible entry modes in terms of nonprofit objectives. The entry mode that ranks highest on risk-adjusted profit contribution may not rank highest on certain nonprofit objectives. Nonprofit objectives vary from company to company: targets for sales volume, growth, and market share; control; reversibility (the degree to which an entry mode can be undone if a mistake is made); establishment of a reputation, and so on. Managers should be clear about their nonprofit objectives and the importance of those objectives to the company.

4. Ranking by Overall Comparative Assessment

In the final stage, managers should bring together the results of their analyses of profit contribution, risk, and nonprofit objectives to make an overall comparative assessment of the feasible entry modes. As stated earlier, there is no objective procedure to capture the three analyses in a single number. Inevitably, therefore, managers must use their own judgment in making the overall assessment.

5. A Last Observation

For one reason or another, managers may fail to carry out profit contribution analysis to the degree shown in Tables 6 and 7. But even so, the approach presented here should help them make better entry decisions. Its key advantage is the forcing of a comparison of feasible entry modes so that managers do not accept a workable mode when a better mode is available. A crude use of this approach will still encourage managers to raise the necessary questions about entry modes, and thereby will guide them in the direction of the right entry mode for a target country. Man-agers using this approach will design flexible entry strategies for heterogeneous and changing international markets. To use a colloquial expression, flexibility is the name of the game.

Source: Root Franklin R. (1998), Entry Strategies for International Markets, Jossey-Bass; 2nd edition.

I’m truly enjoying the design and layout of your

blog. It’s a very easy on the eyes which makes it

much more enjoyable for me to come here and visit more often.

Did you hire out a developer to create your theme?

Great work!

Hey there, You have done a fantastic job. I’ll certainly digg it and personally suggest to my friends.

I am confident they will be benefited from this website.

You should take part in a contest for one of the best blogs on the web. I will recommend this site!