After you have conducted your bibliographical research, one of the first things you can do to begin writing your thesis is to compose the title, the introduction, and the table of contents—that is, exactly all those things that most authors do at the end. This advice seems paradoxical: why start from the end? For one thing, consider that the table of contents usually appears at the beginning of a work, so that the reader can immediately get an idea of what he will find as he reads. Similarly, if you begin writing your thesis by composing the table of contents, it may provide a clearer idea of what you must write. It can function as a working hypothesis, and it can be useful to immediately define the limits of your thesis.

You may object to this idea, realizing that as you proceed in the work, you will be forced to repeatedly revise this hypothetical table of contents, or perhaps rewrite it altogether. This is certainly true, but you will restructure it more effectively if you have a starting point from which to work. Imagine that you have a week to take a 600-mile car trip. Even if you are on vacation, you will not leave your house and indiscriminately begin driving in a random direction. You will make a rough plan. You may decide to take the Milan-Naples highway, with slight detours through Florence, Siena, Arezzo, possibly a longer stop in Rome, and also a visit to Montecassino. If you realize along the way that Siena takes you longer than anticipated, or that it is also worth visiting San Gimignano, you may decide to eliminate Montecassino. Once you arrive in Arezzo, you may have the sudden, irrational, last-minute idea to turn east and visit Urbino, Perugia, Assisi, and Gubbio. This means that—for substantial reasons—you may change your itinerary in the middle of the voyage. But you will modify that itinerary, and not no itinerary.

So it happens with your thesis. Make yourself a provisional table of contents and it will function as your work plan. Better still if this table of contents is a summary, in which you attempt a short description of every chapter. By proceeding in this way, you will first clarify for yourself what you want to do. Secondly, you will be able to propose an intelligible project to your advisor. Thirdly, you will test the clarity of your ideas. There are projects that seem quite clear as long as they remain in the author’s mind, but when he begins to write, everything slips through his fingers. He may have a clear vision of the starting and ending points, but then he may realize that he has no idea of how to get from one to the other, or of what will occupy the space between. A thesis is like a chess game that requires a player to plan in advance all the moves he will make to checkmate his opponent.

To be more precise, your work plan should include the title, the table of contents, and the introduction. Composing a good title is already a project. I am not talking about the title on the first page of the document that you will deliver to the Registrar’s Office many months from now, one that will invariably be so generic as to allow for infinite variations. I am talking of the “secret title” of your thesis, the one that then usually appears as the subtitle. A thesis may have as its “public” title “Radio Commentary and the Attempted Murder of Palmiro Togliatti,” but its subtitle (and its true topic) will be “Radio Commentators’ Use of Gino Barta- li’s Tour de France Victory to Distract the Public from the Attempted Murder of Palmiro Togliatti.” This is to say that after you have focused on a theme, you must decide to treat only one specific point within that theme. The formulation of this point constitutes a sort of question: has there in fact been a deliberate political use of a sport celebrity’s victory to distract the public from the attempted murder of the Italian Communist Party leader Palmiro Togliatti? And can a content analysis of the radio news commentary reveal such an effort? In this way the secret title (turned into a question) becomes an essential part of the work plan.

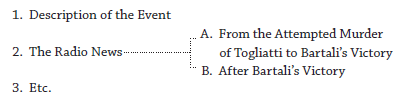

After you have formulated this question, you must subdivide your topic into logical sections that will correspond to chapters in the table of contents. For example:

- Critical Literature on the Topic

- The Event

- The Radio News

- Quantitative Analysis of the News and Its Programming Schedule

- Content Analysis of the News

- Conclusions

Or you can plan a development of this sort:

- The Event: Synthesis of the Various Sources of Information

- Radio News Commentary on the Attempted Murder before Bartali’s Victory

- Radio News Commentary on the Attempted Murder over the Three Days Following Bartali’s Victory

- Quantitative Comparison between the Two Sets of News

- Comparative Content Analysis of the Two Sets of News

- Sociopolitical Evaluation

Ideally the table of contents should be more detailed than this example, as we have already said. If you wish, you can write it on a large sheet of paper with the titles in pencil, canceling them and substituting others as you proceed, so that you can track the phases of the reorganization.

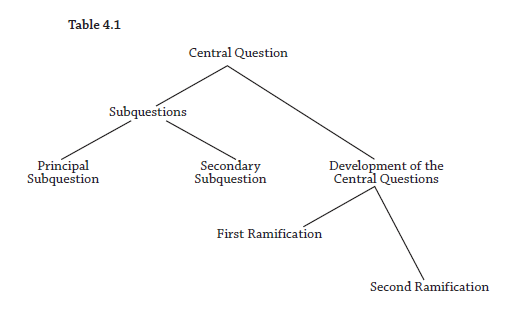

Another method to compose the hypothetical table of contents is the tree structure:

This method allows you to add various branches. Whatever method you use, a hypothetical table of contents should contain the following:

- The state of the issue,

- The previous research,

- Your hypothesis,

- Your supporting data,

- Your analysis of the data,

- The demonstration of your hypothesis,

- Conclusions and suggestions for further research.

The third phase of the work plan is to draft the introduction. The draft should consist of an analytical commentary related to the table of contents: “With this work we propose to demonstrate this thesis. The previous research has left many questions unanswered, and the data gathered is still insufficient. In the first chapter, we will attempt to establish this point; in the second chapter we will tackle this other point. In conclusion, we will attempt to demonstrate a, b, and c. We have set these specific limits for the work. Within these limits, we will use the following method.” And so on.

The function of this fictitious introduction (fictitious, because you will rewrite it many times before you finish your thesis) is to allow you to give your ideas a primary direction that will not change, unless you consciously restructure the table of contents. This way, you will control your detours and your impulses. This introduction is also useful for telling your advisor what you want to do. But it is even more useful for determining whether your ideas are organized. Imagine an Italian student who graduates from high school, where he presumably learned to write because he was assigned an immense quantity of essays. Then he spends four, five, or six years at the university, where he is generally not required to write. When the time comes to write his thesis, he finds himself completely out of practice.1 Writing his thesis will be a great shock, and it is a bad idea to postpone the writing process until the last minute. Since the student would ideally begin writing as soon as possible, it would be prudent for him to start by writing his own work plan.

Be careful, because until you are able to write a table of contents and an introduction, you cannot be sure that what you are writing is your thesis. If you cannot write the introduction, it means that you do not yet have clear ideas on how to begin. If you do in fact have clear ideas on how to begin, it is because you at least suspect where you will arrive. And it is precisely on the basis of this suspicion that you must write your introduction, as if it were a review of the already completed work. Also, do not be afraid to go too far with your introduction, as there will always be time to step back.

At this point, it should be clear that you will continuously rewrite the introduction and the table of contents as you proceed in your work. This is the way it is done. The final table of contents and introduction (those that will appear in the final manuscript) will be different from these first drafts. This is normal. If this were not the case, it would mean that all of your research did not inspire a single new idea. Even if you are determined enough to follow your precise plan from beginning to end, you will have missed the point of writing a thesis if you do not revise as you progress with your work.

What will distinguish the first from the final draft of your introduction? The fact that in the latter you will promise much less than you did in the former, and you will be much more cautious. The goal of the final introduction will be to help the reader penetrate the thesis. Ideally, in the final introduction you will avoid promising something that your thesis does not provide. The goal of a good final introduction is to so satisfy and enlighten the reader that he does not need to read any further. This is a paradox, but often a good introduction in a published book provides a reviewer with the right ideas, and prompts him to speak about the book as the author wished. But what if the advisor (or others) read the thesis and noticed that you announced in the introduction results that you did not realize? This is why the introduction must be cautious, and it must promise only what the thesis will then deliver.

The introduction also establishes the center and periphery of your thesis, a distinction that is very important, and not only for methodological reasons. Your committee will expect you to be significantly more comprehensive on what you have defined as the center than on what you have defined as the periphery. If, in a thesis on the partisan war in Monferrato, you establish that the center is the movements of the badogliane formations, the committee will forgive a few inaccuracies or approximations with regard to the gari- baldine brigades, but will require complete information on the Franchi and Mauri formations.2 To determine the center of your thesis, you must make some decisions regarding the material that is available to you. You can do this during the bibliographical research process described in chapter 3, before you compose your work plan in the manner described at the beginning of this chapter.

By what logic should we construct our hypothetical table of contents? The choice depends on the type of thesis. In a historical thesis, you could have a chronological plan (for example, “The Persecutions of Waldensians in Italy”), or a cause and effect plan (for example, “The Causes of the Israe- li-Palestinian Conflict”). You could also choose a spatial plan (“The Distribution of Circulating Libraries in the Canavese Geographical Region”) or a comparative-contrastive plan (“Nationalism and Populism in Italian Literature in the Great War Period”). In an experimental thesis you could have an inductive plan, in which you would move from particular evidence to the proposal of a theory. A logical-mathematical thesis might require a deductive plan, beginning with the theory’s proposal, and moving on to its possible applications to concrete examples. I would argue that the critical literature on your topic can offer you good examples of work plans, provided you use it critically, that is, by comparing the various approaches to find the example that best corresponds to the needs of your research question.

The table of contents already establishes the logical subdivision of the thesis into chapters, sections, and subsections. On the modalities of this subdivision see section 6.4. Here too, a good binary subdivision allows you to make additions without significantly altering the original order. For example:

- Central Question

- Subquestions

- Principal Subquestion

- Secondary Subquestion

- Development of the Central Question

- First Ramification

- Second Ramification

- Subquestions

You can also represent this structure as a tree diagram with lines that indicate successive ramifications, and that you may introduce without disturbing the work’s general organization:

Once you have arranged the table of contents, you must make sure to always correlate its various points to your index cards and any other documentation you are using. These correlations must be clear from the beginning, and clearly displayed through abbreviations and/or colors, so that they can help you organize your cross-references. You have already seen examples of cross-references in this book. Often the author speaks of something that has already been treated in a previous chapter, and he refers, in parentheses, to the number of the chapter, section, or subsection. These cross-references avoid unnecessary repetition, and also demonstrate the cohesion of the work as a whole. A cross-reference can signify that the same concept is valid from two different points of view, that the same example demonstrates two different arguments, that what has been said in a general sense is also applicable to a specific point in the same study, and so on. A well-organized thesis should abound in cross-references. If there are none, it means that every chapter proceeds on its own, as if everything that has been said in the previous chapters no longer matters. There are undoubtedly thesis types (for example collections of documents) that can work this way, but cross-references should become necessary at least in their conclusions. A well-written hypothetical table of contents is the numerical grid that allows you to create cross-references, instead of needlessly shuffling through papers and notes to locate a specific topic. This is how I have written the very book you are reading.

So as to mirror the logical structure of the thesis (topic, center and periphery, ramifications, etc.), the table of contents must be articulated in chapters, sections, and subsections. To avoid long explanations, I suggest that you take a look at this book’s table of contents. This book is rich in sections and subsections, and sometimes even more minute subdivisions not included in the table of contents. (For example, see section 3.2.3. These smaller subdivisions help the reader understand the argument.) The example below illustrates how a table of contents should mirror the logical structure of the thesis. If a section 1.2.1 develops as a corollary to 1.2, this must be graphically represented in the table of contents:

TABLE OF CONTENTS

- The Subdivision of the Text

- The Chapters

- Spacing

- Indentation

- The Sections

- Different Kinds of Titles

- Possible Subdivision in Subsections

- The Final Draft

- Typing Agency or Typing on Your Own

- The Cost of a Typewriter

- The Bookbinding

- The Chapters

This example also illustrates that the different chapters need not necessarily adhere to the same pattern of subdivision. The nature of the argument may require that one chapter be divided into many sub-subsections, while another can proceed swiftly and continuously under a general title.

A thesis may not require many divisions. Also, subdivisions that are too minute may interrupt the continuity of the argument. (Think, for example, of a biography.) But keep in mind that a detailed subdivision helps to control the subject, and allows readers to follow your argument. For example, if I see that an observation appears under subsection 1.2.2, I know immediately that it is something that refers to section 2 of chapter 1, and that it has the same importance as the observation under subsection 1.2.1.

One last observation: only after you have composed a solid table of contents may you allow yourself to begin writing other parts of your thesis, and at this point you are not required to start with the first chapter. In fact, usually a student begins to draft the part of his thesis about which he feels most confident, and for which he has gathered the best documentation. But he can do this only if, in the background, there is the table of contents providing a working hypothesis.

Source: Eco Umberto, Farina Caterina Mongiat, Farina Geoff (2015), How to write a thesis, The MIT Press.

Hi, Neat post. There’s a problem along with your site in internet explorer, might test this?K IE nonetheless is the marketplace chief and a big part of other people will leave out your great writing because of this problem.

Saved as a favorite, I really like your blog!

What’s Taking place i am new to this, I stumbled upon this I’ve found It absolutely useful and it has aided me out loads. I am hoping to contribute & assist other users like its helped me. Great job.