1. Various Types of Index Cards and Their Purpose

Begin to read the material as your bibliography grows. It is unrealistic to think that you will compile a complete bibliography before you actually begin to read. In practice, after putting together a preliminary list of titles, you can immerse yourself in these. Sometimes, before a student even starts a bibliography, he begins by reading a single book, and from its citations he begins to compile a bibliography. In any case, as you read books and articles, the references thicken, and the bibliography file that we have described in chapter 3 grows bigger.

Ideally, when you begin writing your thesis, you would have all the necessary books at home, both new and antique (and you would have a personal library, and a comfortable and spacious working environment where you can divide the books that you will be using into different piles, arranged on many tables). But this ideal condition is very rare, even for a professional scholar. In any case, let us imagine that you have been able to locate and purchase all the books that you need. In principle, the only index cards you will need at this point are the bibliographical cards I have described in section 3.2.2. You will prepare your work plan (i.e., the title, introduction, and table of contents) with your chapters and sections numbered progressively, and as you read the books you will underline them, and you will write in the margins the abbreviations of your table of contents’ various chapters. Similarly, you will place a book’s abbreviation and the page number near the chapters in your table of contents, so that you will know where to look for an idea or quote when the time comes for writing.

Let us look at a specific example. Suppose you write a thesis on “The Concept of Possible Worlds in American Science Fiction,” and that subsection 4.5.6 of your plan is “The Time Warp as a Gateway to Possible Worlds.” As you read chapter 21, page 132 of Robert Sheckley’s Mindswap (New York: Delacorte Press, 1966), you will learn that Marvin’s Uncle Max “stumbled into a time warp” while playing golf at the Fairhaven Country Club in Stanhope, and found himself transferred to the planet Celsus V. You will write the following in the margin:

T.(4.5.6) time warp

This note refers to a specific subsection of your thesis (you may in fact use the same book ten years later and take notes for another project, so it is a good idea to know to what project a note refers). Similarly, you will write the following in subsection 4.5.6 of your work plan:

cf.Scheckley, Mindswap, 132

In this area, you will already have noted references to Fred- ric Brown’s What Mad Universe and Robert A. Heinlein’s The Door into Summer.

However, this process makes a few assumptions: (a) that you have the book at home, (b) that you own it and therefore can underline it, and (c) that you have already formulated the work plan in its final form. Suppose you do not have the book, because it is rare and the only copy you can find is in the library; or you have it in your possession, but you have borrowed it and cannot underline it; or that you own it, but it might happen to be an incunabulum of inestimable value; or that, as we have already said, you must continually restructure the work plan as you go. Here you will run into difficulties. This last situation is the most common; as you proceed the plan grows and changes, and you cannot continuously revise the notes you have written in the margins of your books. Therefore these notes should be generic, for example, “possible worlds.”

But how can you compensate for the imprecision of such a note? By creating idea index cards and keeping them in an idea file. You can use a series of index cards with titles such as “Parallelisms between Possible Worlds,” “Inconsistencies,” “Structure Variations,” “Time Warps,” etc. For example, the “Time Warps” card will contain a precise reference to the pages in which Sheckley discusses this concept. Afterward you can place all the references to time warps at the designated point of your final work plan, yet you can also move the index card, merge it with the others, and place it before or after another card in the file. Similarly, you might find it useful to create thematic index cards and the appropriate file, ideal for a thesis on the history of ideas. If your work on possible worlds in American science fiction explores the various ways in which different authors confronted various logical-cosmological problems, this type of file will be ideal.

But let us suppose that you have decided to organize your thesis differently, with an introductory chapter that frames the theme, and then a chapter for each of the principal authors (Sheckley, Heinlein, Asimov, Brown, etc.), or even a series of chapters each dedicated to an exemplary novel. In this case, you need an author file. The author index card “Sheckley” will contain the references needed to find the passages in which he writes about possible worlds. And you may also choose to divide this file into sections on “Time Warps,” “Parallelisms,” “Inconsistencies,” etc.

Let us suppose instead that your thesis addresses the question in a much more theoretical way, using science fiction as a reference point but in fact discussing the logic of possible worlds. The science fiction references will be less systematic, and will instead serve as a source of entertaining quotes. In this case, you will need a quote file, where you will record on the “Time Warps” index card a particularly apt phrase from Sheckley; and on the “Parallelisms” index card, you will record Brown’s description of two perfectly identical universes where the only variation is the lacing pattern of the protagonist’s shoelaces. And so on.

But what if Sheckley’s book is not currently available, but you remember reading it at a friend’s house in another city, long before you envisioned a thesis that included themes of time warps and parallelism? In this case, you fortunately prepared a readings index card on Mindswap at your friend’s house, including its bibliographical information, a general summary, a series of evaluations addressing its importance, and a series of quotes that at the time seemed particularly apt. (See sections 3.2.2 and 4.2.3 for more information on the readings file.)

So depending on the context, we can create index cards of various types: connection index cards that link ideas and sections of the work plan; question index cards dealing with how to confront a particular problem; recommendation index cards that note ideas provided by others, suggestions for further developments, etc. Each type of index card should have a different color, and should include in the top right corner abbreviations that cross-reference one series of cards to another, and to the general plan. The result is something majestic.

But must you really write all these index cards? Of course not. You can have a simple readings file instead, and collect all your other ideas in notebooks. You can limit yourself to the quote file because your thesis (for example, “The Feminine in Women Writers of the 1940s”) starts from a very precise plan, has little critical literature to examine, and simply requires you to collect abundant textual material. As you can see, the nature of the thesis suggests the nature of the index cards.

My only suggestion is that a given file be complete and unified. For example, suppose that you have books by Smith, Rossi, Braun, and De Gomera at home, while in the library you have read books by Dupont, Lupescu, and Nagasaki. If you file only these three, and rely on memory (and on your confidence in their availability) for the other four, how will you proceed when the time comes to begin writing? Will you work half with books and half with index cards? And if you have to restructure your work plan, what materials will you need? Books, index cards, notebooks, or notes? Rather, it will be useful to file cards on Dupont, Lupescu, and Nagasaki in full and with an abundance of quotes, but also to create more succinct index cards for Smith, Rossi, Braun, and De Gomera, perhaps by documenting the page numbers of relevant quotes, instead of copying them in their entirety. At the very least, always work on homogeneous material that is easy to move and handle. This way, you will know at a glance what you have read and what remains to be read.

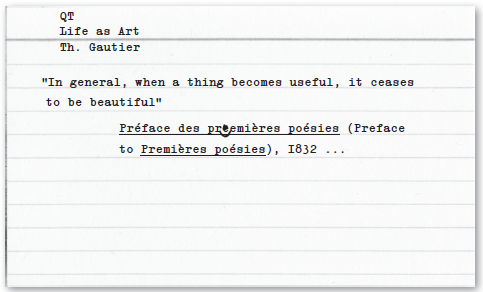

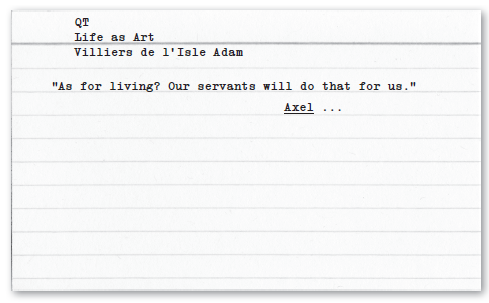

With that said, in some cases it is convenient and useful to put everything on index cards. Imagine a literary thesis in which you must find and comment on many significant quotes on the same topic, but originating from many different authors. Suppose your topic is “The Concept of Life as Art in Romantic and Decadent Writers.” In table 4.2 you will find examples of four index cards that gather useful quotes on this topic. As you can see, each index card bears in the top left corner the abbreviation “QT” to distinguish it from other types of index cards, and then includes the theme “Life as Art.” Why do I specify the theme even though I already know what it is? Because the thesis could develop so that “Life as Art” becomes only a part of the work; because this file could also serve me after the thesis and end up merged with a quote file on other themes; because I could find these cards 20 years later and ask myself what the devil they refer to. In addition to these two headings, I have noted the quote’s author. In this case, the last name suffices because you are supposed to already have biographical index cards on these authors, or have written about them at the beginning of your thesis. Finally, the body of the index card bears the quote, however short or long it may be. (It could be short or very long.)

Let us look at the index card for Whistler. There is a quote in Italian followed by a question mark. This means that I found the sentence quoted in another author’s book, but I am not sure where it comes from, whether it is correct, or whether the original is in English. After I started this card, I happened to find the original text, and I recorded it along with the appropriate references. I can now use this index card for a correct citation.

Let us turn to the card for Villiers de l’Isle Adam. I have written the quote from the English translation of the French original.3 I know what book it comes from, but the information is incomplete. This is a good example of an index card that I must complete. Similarly incomplete is the card for Gautier.4 Wilde’s index card is complete, however, with the original quote in English.

Now, I could have found Wilde’s original quote in a copy of the book that I have at home, but shame on me if I neglected writing the index card, because I will forget about it by the time I am finishing my thesis. Shame on me also if I simply wrote on the index card “see page xxxiv” without copying the quote, because when the time comes to write my thesis, I will need all of the texts at hand in order to copy the exact quotations. Therefore, although writing index cards takes some time, it will save you much more in the end.

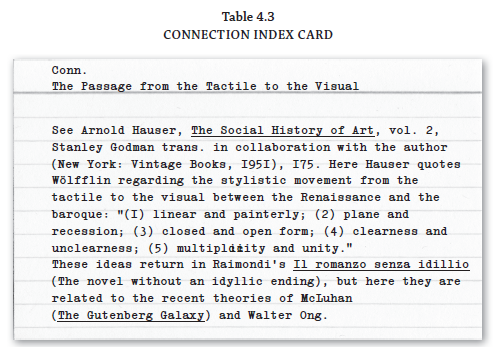

Table 4.3 shows an example of a connection index card for the thesis on metaphor in seventeenth-century treatise writers that we discussed in section 3.2.4. Here I used the abbreviation “Conn.” to designate the type of card, and I wrote a topic that I will research in depth, “The Passage from the Tactile to the Visual.” I do not yet know if this topic will become a chapter, a small section, a simple footnote, or even (why not?) the central topic of the thesis. I annotated some ideas that came to me from reading a certain author, and indicated the books to consult and the ideas to develop. As I page through my index cards once the first draft of my thesis is completed, I will see whether I have neglected an idea that was important, and I will need to make some decisions: revise the thesis to make this idea fit; decide that it was not worth developing; insert a footnote to show that I had the idea in mind, but did not deem its development appropriate for that specific topic. Once I have completed the thesis, I could also decide to dedicate my future research precisely to that idea. Remember that an index card file is an investment that you make during your thesis, but if you intend to keep studying, it will pay off years—and sometimes decades—later.

I will not elaborate further on the various types of index cards. Let us limit ourselves to discussing how to organize the primary sources, along with the readings index cards of the secondary sources.

2. Organizing the Primary Sources

Readings index cards are useful for organizing critical literature. I would not use index cards, or at least not the same kind of index cards, to organize primary sources. In other words, if you compose a thesis on Joyce, you will naturally write index cards for all the books and articles on Joyce that you are able to find, but it would be strange to create index cards for Ulysses or Finnegans Wake. The same would apply if you wrote a thesis on articles of the Italian Civil Code, or a thesis in the history of mathematics on Felix Klein’s Erlangen Program. Ideally you will always have the primary sources at hand. This is not difficult, as long as you are dealing with books by a classic author available in many good critical editions, or those by a contemporary author that are readily available on the market. In any case, the primary sources are an indispensable investment. You can underline a book or a series of books that you own, even in various colors. Let us talk briefly about underlining:

Underlining personalizes the book. The marks become traces of your interest. They allow you to return to the book even after a long period, and find at a glance what originally interested you. But you must underline sensibly. Some people underline everything, which is equivalent to not underlining at all. On the other hand, it is possible that on the same page there is information that interests you on different levels. In that case, it is essential to differentiate the underlining.

Use colors. Use markers with a fine point. Assign a color to each topic, and use the same colors on the work plan and the various index cards. This will be useful when you are drafting your work, because you will know right away that red refers to passages important for the first chapter, and green to those important for the second chapter.

Associate an abbreviation with each color (or use abbreviations instead of the colors). For example, going back to our topic of possible worlds in science fiction, use the abbreviation “TW” to signal everything pertinent to time warps, or “I” to mark inconsistencies between possible worlds. If your thesis concerns multiple authors, assign an abbreviation to each of them.

Use abbreviations to emphasize the relevance of information. A bracket with the annotation “IMP” can signify a very important passage, and you will not need to underline each individual line. “QT” will indicate not only that the passage is important, but that you also want to quote it in its entirety. “QT/TW” will indicate that the passage is an ideal quote to illustrate the question of time warps.

Use abbreviations to designate the passages you must reread. Some passages may seem obscure to you when you first read them. You can mark the top margins of these pages with a big “R,” so that you know you must review them as you go deeper into the subject, and after other readings have clarified these ideas for you.

When should you not underline? When the book is not yours, obviously, or if it is a rare edition of great commercial value that you cannot modify without devaluing. In these cases, photocopy the important pages and underline those. Or get a small notebook where you can copy the salient passages, with your comments interspersed. Or develop a special file for the primary sources, although this would require a huge effort, because you would have to practically catalog the texts page by page. However, this can work if your thesis is on Alain-Fournier’s Le grand Meaulnes (The Wanderer), a very short little book. But what if it is on Hegel’s The Science of Logic? And what if, returning to our experiment in Alessandria’s library (section 3.2.4), you must catalog the seventeenth-century edition of Tesauro’s Cannocchiale aristotelico? You will have to resort to photocopies and the aforementioned notebook, annotated throughout with colors and abbreviations.

Supplement the underlining with adhesive page markers. Copy the abbreviations and colors on the portion of the marker that sticks out from the pages.

Beware the “alibi of photocopies”! Photocopies are indispensable instruments. They allow you to keep with you a text you have already read in the library, and to take home a text you have not read yet. But a set of photocopies can become an alibi. A student makes hundreds of pages of photocopies and takes them home, and the manual labor he exercises in doing so gives him the impression that he possesses the work. Owning the photocopies exempts the student from actually reading them. This sort of vertigo of accumulation, a neocapitalism of information, happens to many. Defend yourself from this trap: as soon as you have the photocopy, read it and annotate it immediately. If you are not in a great hurry, do not photocopy something new before you own (that is, before you have read and annotated) the previous set of photocopies. There are many things that I do not know because I photocopied a text and then relaxed as if I had read it.

If the book is yours and it does not have antiquarian value, do not hesitate to annotate it. Do not trust those who say that you must respect books. You respect books by using them, not leaving them alone. Even if the book is unmarked, you won’t make much money reselling it to a bookseller, so you may as well leave traces of your ownership.

3. The Importance of Readings Index Cards

Among all the types of index cards we have discussed, the most common and the most indispensable are the readings index cards. These are where you precisely annotate all the references contained in a book or article, transcribe key quotes, record your evaluation, and append other observations. In short, the readings index card perfects the bibliographical index card described in section 3.2.2. The latter contains only the information useful for tracking down the book, while the former contains all the information on a book or article, and therefore must be much larger. You can use standard formats or make your own cards, but in general they should correspond to half a letter-size (or half an A4-size) sheet. They should be made of cardboard, so that you can easily page through them in the index card box, or gather them into a pack bound with a rubber band. They should be made of a material appropriate for both a ballpoint and a fountain pen, so that they do not absorb or diffuse the ink, but instead allow the pen to run smoothly. Their structure should be more or less that of the model index cards proposed in tables 4.4 through 4.11.

Nothing prohibits you from filling up many index cards, and this might actually be a good idea for important books. The cards should be numbered consecutively, and the front of each card should bear abbreviated information about the book or article in question. There are many ways to catalog the book on your readings index card. Your method also depends on your memory, as there are people who have poor memories and need to write everything, and others who only require a quick note. Let us say that the following is the standard method:

- Record precise bibliographical information that is, if possible, more complete than that you have recorded on the bibliographical index card. The latter helped you locate the book, while the readings index card will help you talk about the book and cite it properly in the final bibliography. You should have the book in your hands when you write the readings index card, so that you can obtain all the available information, such as the edition, the publisher’s information, etc.

- Record the author’s information, if he is not a well- known authority.

- Write a short (or long) summary of the hook or article.

- Transcribe the full text of passages you wish to quote (assuming you are not already using a quote file for this purpose). Use quotation marks and note precisely the page number or numbers. You may also want to record extra quotes to provide context when you are writing. Be sure not to confuse a quote with a paraphrase! (See section 5.3.2.)

- Record your personal comments throughout your summary. To avoid mistaking them for the author’s own thoughts, write your comments inside square brackets, and in color.

- Mark the card with the appropriate abbreviation or color so that it clearly corresponds to the correct section of your work. If your card refers to multiple sections, write multiple abbreviations. If it refers to the thesis as a whole, designate this somehow.

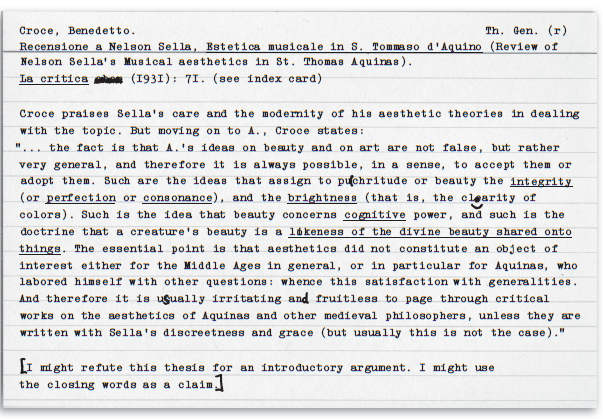

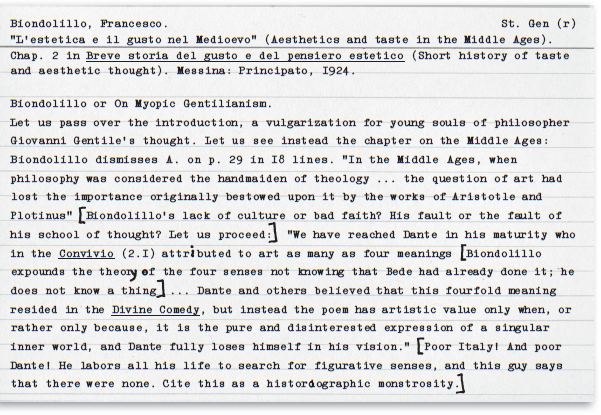

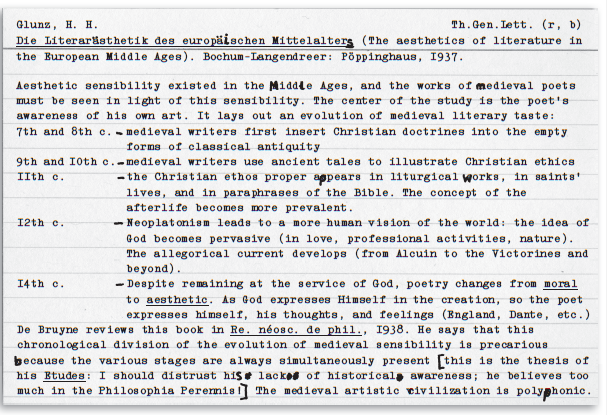

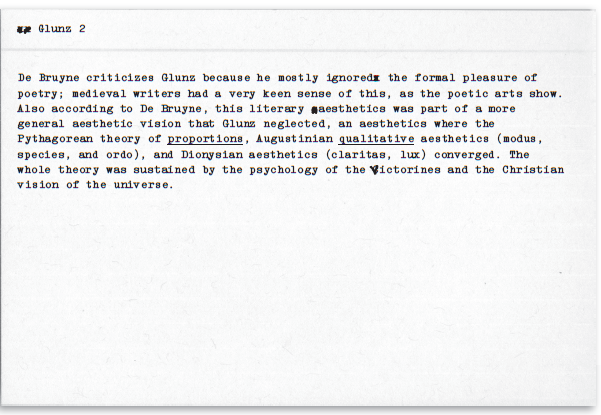

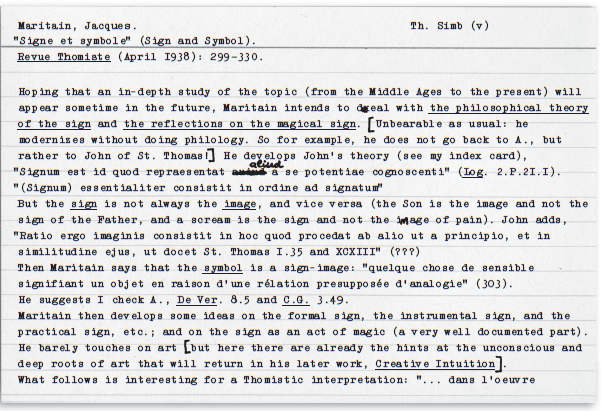

So that we can avoid further generalities, let me provide some practical examples. In tables 4.4 through 4.11 you will find some examples of readings index cards. Instead of inventing topics and methods, I retrieved the index cards from my own thesis, “The Aesthetics of Thomas Aquinas.” My filing method is not necessarily the best one. These index cards provide an example of a method that facilitated different types of index cards. You will see that I was not as precise as I recommend that you be. Much information is missing, while other information is excessively elliptical. In fact I learned some of the lessons in this book later in my career, but it is not a given that you should make the same mistakes that I did. I have not altered the style or obscured the naivete of these examples, and you can take them for what they are worth. (Notice that I only provide examples of index cards on which an entire work fit. To preserve space, I do not provide examples of index cards referring to what became the main sources of my work, because each of these required ten index cards.) Let us go over these examples one by one:

- Croce index card: This was a short review, important because of the author. Since I had already found the book reviewed, I copied only this single, significant opinion. Look at the final squared brackets: that statement represents exactly what I did in my thesis, two years later. Biondolillo index card: This is a polemical index card, showing all the irritation of the neophyte who sees his argument scorned. I found it necessary to record my ideas this way, perhaps to insert a polemical note in my work. Glunz index card: I quickly consulted with a German friend who helped me understand precisely what this thick book discussed. This book did not have immediate relevance to my work, but it was perhaps worthy of a note.

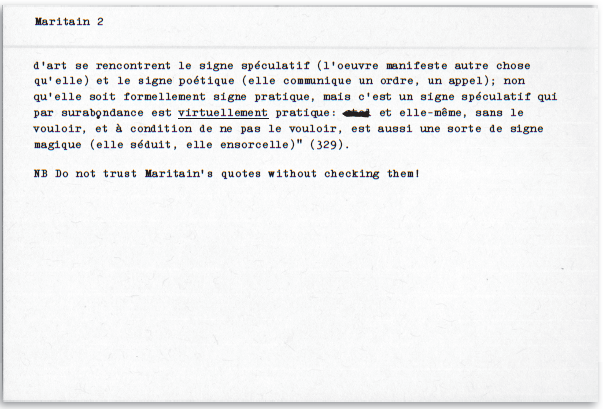

- Maritain index card: I already knew Art and Scholasticism, this author’s fundamental work, but I did not find him very trustworthy. At the end of the card, I made a note that would remind me not to trust the accuracy of his quotes without a subsequent check.

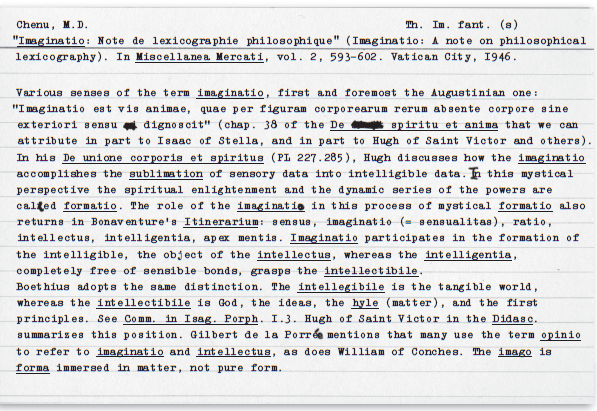

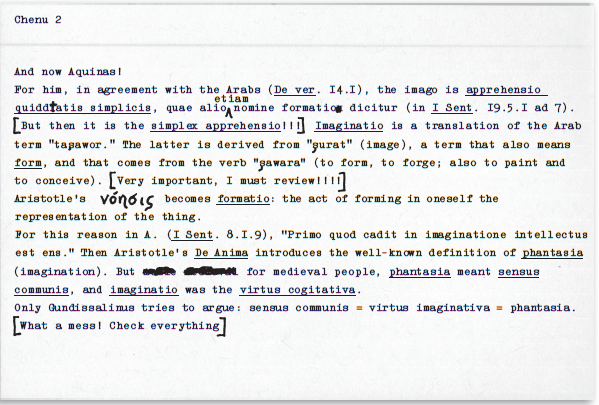

- Chenu index card: This is a short essay by a serious scholar on a very important theme in my work, and I squeezed as much juice from it as I could. This essay was the classic case of an indirect source; I noted only what I could then check directly. This card was more of a bibliographical supplement than a readings index card.

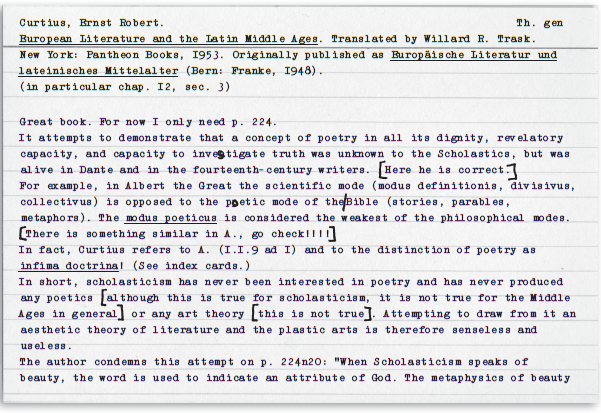

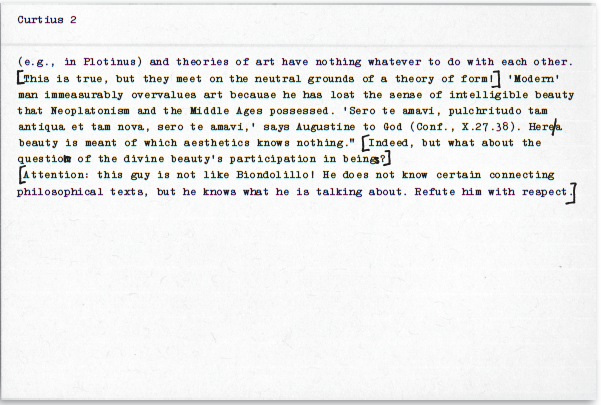

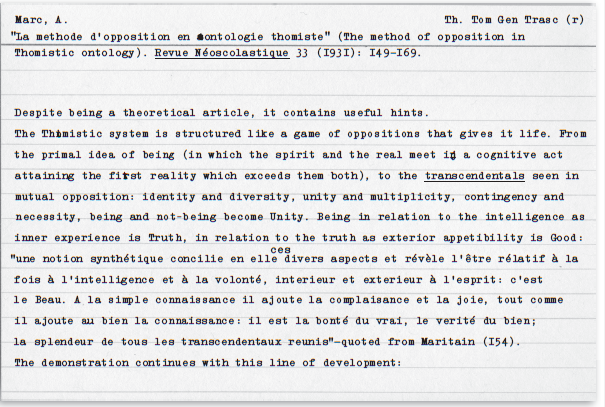

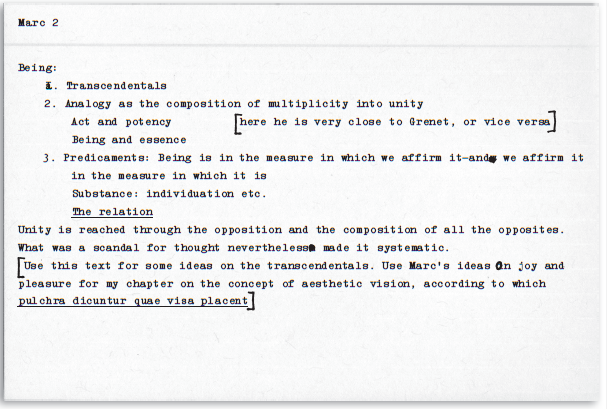

- Curtius index card: An important book that I consulted only for a particular section. I was in a hurry, so I only skimmed the rest of the book. I did return to it and read it later for other purposes, after I completed my thesis. Marc index card: An interesting article from which I extracted the juice.

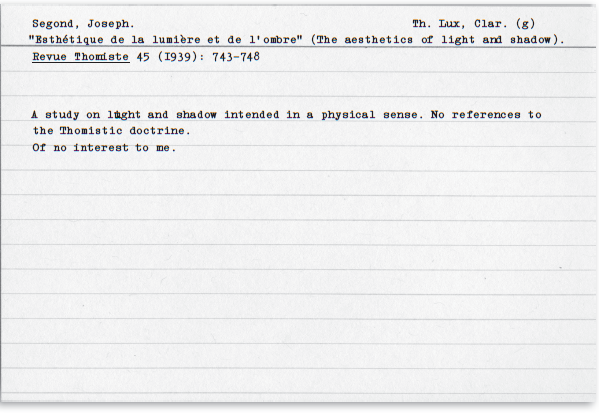

- Segond index card: This is what we might call a “disposal” index card, as its purpose was essentially to remind me that I did not need this source for my thesis.

As you can see, I used abbreviations in the top right corner of these cards in the manner I have described above. In fact, the lower-case letters in parentheses replace colored points that were on the original cards. There is no need for me to explain exactly to what these referred; it is only important to note that I used them to organize my cards.

4. Academic Humility

Do not let this subsection’s title frighten you. It is not an ethical disquisition. It concerns reading and filing methods.

You may have noticed that on one of the cards, as a young scholar, I teased the author Biondolillo by dismissing him in a few words. I am still convinced that I was justified in doing so, because the author attempted to explain the important topic of the aesthetics of Thomas Aquinas in only 18 lines. This case was extreme, but I filed the card on the book, and I noted the author’s opinion anyway. I did this not only because we must record all the opinions expressed on our topic, but also because the best ideas may not come from the major authors. And now, to prove this, I will tell you the story of the abbot Vallet.

To fully understand this story, I should explain the question that my thesis posed, and the interpretive stumbling block that obstructed my work for about a year. Since this problem is not of general interest, let us say succinctly that for contemporary aesthetics, the moment of the perception of beauty is generally an intuitive moment, but for St. Thomas the category of intuition did not exist. Many contemporary interpreters have striven to demonstrate that he had somehow talked about intuition, and in the process they did violence to his work. On the other hand, St. Thomas’s moment of the perception of objects was so rapid and instantaneous that it did not explain the enjoyment of complex aesthetic qualities, such as the contrast of proportions, the relationship between the essence of a thing and the way in which this essence organizes matter, etc. The solution was (and I arrived at it only a month before completing my thesis) in the discovery that aesthetic contemplation lay in the much more complex act of judgment. But St. Thomas did not explicitly say this. Nevertheless, the way in which he spoke of the contemplation of beauty could only lead to this conclusion. Often this is precisely the scope of interpretive research: to bring an author to say explicitly what he did not say, but that he could not have avoided saying had the question been posed to him. In other words, to show how, by comparing the various statements, that answer must emerge, in the terms of the author’s scrutinized thought. Maybe the author did not give the answer because he thought it obvious, or because—as in the case of St. Thomas—he had never organically treated the question of aesthetics, but always discussed it incidentally, taking the matter for granted.

Therefore, I had a problem, and none of the authors I was reading helped me solve it (although if there was anything original in my thesis, it was precisely this question, with the answer that was to come out of it). And one day, while I was wandering disconsolate and looking for texts to aid me, I found at a stand in Paris a little book that attracted me at first for its beautiful binding. I opened it and found that it was a book by a certain abbot Vallet, titled L’idee du Beau dans la philosophie de Saint Thomas d’Aquin (The idea of beauty in the philosophy of St. Thomas Aquinas) (Louvain, 1887). I had not found it in any bibliography. It was the work of a minor nineteenth-century author. Naturally I purchased it (and it was even inexpensive). I began to read it, and I realized that the abbot Vallet was a poor fellow who repeated preconceived ideas and did not discover anything new. If I continued to read him, it was not for “academic humility,” but for pure stubbornness, and to recoup the money I had spent. (I did not know such humility yet, and in fact I learned it reading that book. The abbot Vallet was to become my great mentor.) I continued reading, and at a certain point—almost in parentheses, said probably unintentionally, the abbot not realizing his statement’s significance—I found a reference to the theory of judgment linked to that of beauty. Eureka! I had found the key, provided by the poor abbot Vallet, who had died a hundred years before, who was long since forgotten, and yet who still had something to teach to someone willing to listen.

This is academic humility: the knowledge that anyone can teach us something. Perhaps this is because we are so clever that we succeed in having someone less skilled than us teach us something; or because even someone who does not seem very clever to us has some hidden skills; or also because someone who inspires us may not inspire others. The reasons are many. The point is that we must listen with respect to anyone, without this exempting us from pronouncing our value judgments; or from the knowledge that an author’s opinion is very different from ours, and that he is ideologically very distant from us. But even the sternest opponent can suggest some ideas to us. It may depend on the weather, the season, and the hour of the day. Perhaps, had I read the abbot Vallet a year before, I would not have caught the hint. And who knows how many people more capable than I had read him without finding anything interesting. But I learned from that episode that if I wanted to do research, as a matter of principle I should not exclude any source. This is what I call academic humility. Maybe this is hypocritical because it actually requires pride rather than humility, but do not linger on moral questions: whether pride or humility, practice it.

Source: Eco Umberto, Farina Caterina Mongiat, Farina Geoff (2015), How to write a thesis, The MIT Press.

2 Oct 2021

1 Oct 2021

2 Oct 2021

1 Oct 2021

2 Oct 2021

2 Oct 2021