Is selling a science, with easily taught basic concepts or an art learned through experience? In a survey of 173 marketing executives, 46 percent perceived selling as an art, 8 percent as a science, and 46 percent as an art evolving into a science.[1] The fact that selling is considered an art by some and a science by others has produced two contrasting approaches to the theory of selling.

The first approach distilled the experiences of successful salespeople and, to a lesser extent, advertising professionals. Many such persons, of course, succeeded because of their grasp of practical, or learned-through- experience psychology and their ability to apply it in sales situations. It is not too surprising that these selling theories emphasize the “what to do” and “how to do” rather than the “why.” These theories, based on experiential knowledge accumulated from years of “living in the market” rather than on a systematic, fundamental body of knowledge, are subject to Howard’s dictum, “Experiential knowledge can be unreliable.”[2]

The second approach borrowed findings from the behavioral sciences. The late E.K. Strong, Jr., professor of psychology at the Stanford Graduate School of Business, was a pioneer in this effort, and his “buying formula” theory is presented later in this section. John A. Howard of the Columbia Graduate School of Business was in the forefront of those who adapted the findings of behavioral science to analysis of buying behavior; his “behavioral equation,” discussed later in this section, attempts to develop a unified theory of buying and selling.

In this section we examine five theories. The first two, the “AIDAS” theory and the “right set of circumstances” theory, are seller oriented. The third, the “buying-formula” theory of selling, is buyer oriented. The last two, “the behavioral equation” and the SPIN selling, emphasizes the buyer’s decision process but also takes the salesperson’s influence process into account.

1. AIDAS Theory of Selling

This theory—popularly known as the AIDAS theory, after the initials of the five words used to express it (attention, interest, desire, action, and satisfaction)—is the basis for many sales and advertising texts and is the skeleton around which many sales training programs are organized. Some support for this theory is found in the psychological writings of William James,11 but there is little doubt that the construct is based upon experiential knowledge and, in fact, was in existence as early as 1898.[4] During the successful selling interview, according to this theory, the prospect’s mind passes through five successive mental states: attention, interest, desire, action, and satisfaction. Implicit in this theory is the notion that the prospect goes through these five stages consciously, so the sales presentation must lead the prospect through them in the right sequence if a sale is to happen.

Securing attention. The goal is to put the prospect into a receptive state of mind. The first few minutes of the interview are crucial. The salesperson has to have a reason, or an excuse, for conducting the interview. If the salesperson previously has made an appointment, this phase presents no problem, but experienced sales personnel say that even with an appointment, a salesperson must possess considerable mental alertness, and be a skilled conversationalist, to survive the start of the interview. The prospect’s guard is naturally up, since he or she realizes that the caller is bent on selling something. The salesperson must establish good rapport at once. The salesperson needs an ample supply of “conversation openers.” Favorable first impressions are assured by, among other things, proper attire, neatness, friendliness, and a genuine smile. Skilled sales personnel often decide upon conversation openers just before the interview so that those chosen are as timely as possible. Generally it is advantageous if the opening remarks are about the prospect (people like to talk and hear about themselves) or if they are favorable comments about the prospect’s business. A good conversation opener causes the prospect to relax and sets the stage for the total presentation. Conversation openers that cannot be readily tied in with the remainder of the presentation should be avoided, for once the conversation starts to wander, great skill is required to return to the main theme.

Gaining interest. The second goal is to intensify the prospect’s attention so that it evolves into strong interest. Many techniques are used to gain interest. Some salespeople develop a contagious enthusiasm for the product or a sample. When the product is bulky or technical, sales portfolios, flipcharts, or other visual aids serve the same purpose.

Throughout the interest phase, the hope is to search out the selling appeal that is most likely to be effective. Sometimes, the prospect drops hints, which the salesperson then uses in selecting the best approach. To encourage hints by the prospect, some salespeople devise stratagems to elicit revealing questions. Others ask the prospect questions designed to clarify attitudes and feelings toward the product. The more experienced the salesperson, the more he or she has learned from interviews with similar prospects. But even experienced sales personnel do considerable probing, usually of the question-and-answer variety, before identifying the strongest appeal. In addition, prospects’ interests are affected by basic motivations, closeness of the interview subject to current problems, its timeliness, and their mood—receptive, skeptical, or hostile—and the salesperson must take all these into account in selecting the appeal to emphasize.

Kindling desire. The third goal is to kindle the prospect’s desire to the ready-to-buy point. The salesperson must keep the conversation running along the main line toward the sale. The development of sales obstacles, the prospect’s objections, external interruptions, and digressive remarks can sidetrack the presentation during this phase. Obstacles must be faced and ways found to get around them. Objections need answering to the prospect’s satisfaction. Time is saved, and the chance of making a sale improved if objections are anticipated and answered before the prospect raises them. External interruptions cause breaks in the presentation, and when conversation resumes, good salespeople summarize what has been said earlier before continuing. Digressive remarks generally should be disposed of tactfully, with finesse, but sometimes distracting digression is best handled bluntly, for example, “Well, that’s all very interesting, but to get back to the subject. …”

Inducing actions. If the presentation has been perfect, the prospect is ready to act—that is, to buy. However, buying is not automatic and, as a rule, must be induced. Experienced sales personnel rarely try for a close until they are positive that the prospect is fully convinced of the merits of the proposition. Thus, it is up to the salesperson to sense when the time is right. The trial close, the close on a minor point, and the trick close are used to test the prospect’s reactions. Some sales personnel never ask for a definite “yes” or “no” for fear of getting a “no,” from which they think there is no retreat. But it is better to ask for the order straightforwardly. Most prospects find it is easier to slide away from hints than from frank requests for an order.

Building satisfaction. After the customer has given the order, the salesperson should reassure the customer that the decision was correct. The customer should be left with the impression that the salesperson merely helped in deciding. Building satisfaction means thanking the customer for the order, and attending to matters such as making certain that the order is filled as written, and following up on promises made. The order is the climax of the selling situation, so the possibility of an anticlimax should be avoided—customers sometimes “unsell” themselves and the salesperson should not linger too long.

2. “Right Set of Circumstances” Theory of Selling

“Everything was right for that sale” sums up the second theory. This theory, sometimes called the “situation-response” theory, had its psychological origin in experiments with animals and holds that the particular circumstances prevailing in a given selling situation cause the prospect to respond in a predictable way. If the salesperson succeeds in securing the attention and gaining the interest of the prospect, and if the salesperson presents the proper stimuli or appeals, the desired response (that is, the sale) will result.

Furthermore, the more skilled the salesperson is in handling the set of circumstances, the more predictable is the response.

The set of circumstances, includes factors external and internal to the prospect. To use a simplified example, suppose that the salesperson says to the prospect, “Let’s go out for a cup of coffee.” The salesperson and the remark are external factors. But at least four factors internal to the prospect affect the response. These are the presence or absence of desires: (1) to have a cup of coffee, (2) to have it now, (3) to go out, and (4) to go out with the salesperson.

Proponents of this theory tend to stress external factors and at the expense of internal factors. They seek selling appeals that evoke desired responses. Sales personnel who try to apply the theory experience difficulties traceable to internal factors in many selling situations, but the internal factors are not readily manipulated. This is a seller-oriented theory: it stresses the importance of the salesperson controlling the situation, does not handle the problem of influencing factors internal to the prospect, and fails to assign appropriate weight to the response side of the situation-response interaction.

3. “Buying Formula” Theory of Selling

In contrast to the two previous theories, the third emphasizes the buyer’s side of the buyer-seller dyad. The buyer’s needs or problems receive major attention, and the salesperson’s role is to help the buyer find solutions. This theory purports to answer the question: What thinking process goes on in the prospect’s mind that causes the decision to buy or not to buy?

The buying formula is a schematic representation of a group of responses, arranged in psychological sequence. The buying formula theory emphasizes the prospect’s responses (which, of course, are strongly influenced by internal factors) and de-emphasizes the external factors, on the assumption that the salesperson, being naturally conscious of the external factors, will not overlook them. Since the salesperson’s normal inclination is to neglect the internal factors, the formula is a convenient way to help the salesperson remember.

The origin of this theory is obscure, but recognizable versions appear in a number of early books on advertising and selling by authors who had experiential knowledge of salesmanship.13 Several psychologists also advanced explanations similar to the buying formula.14 The name “buying formula” was given to this theory by the late E.K. Strong, Jr., and the following step-by-step explanation is adapted from his teaching and writings.

Reduced to their simplest elements, the mental processes involved in a purchase are

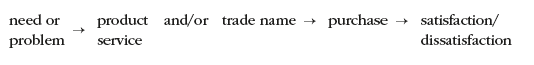

need (or problem) → solution → purchase

Because the outcome of a purchase affects the chance that a continuing relationship will develop between the buyer and the seller, and because nearly all sales organizations are interested in continuing relationships, it is necessary to add a fourth element. The four elements then, are

need (or problem) → solution → purchase → satisfaction

Whenever a need is felt, or a problem recognized, the individual is conscious of a deficiency of satisfaction. In the world of selling and buying, the solution will always be a product or service or both, and they will belong to a potential seller.

In purchasing, then, the element “solution” involves two parts: (1) product (and/or service) and (2) trade name (name of manufacturer, company, or salesperson).

In buying anything, the purchaser proceeds mentally from need or problem to product or service, to trade name, to purchase, and, upon using the product or service, he or she experiences satisfaction or dissatisfaction. Thus, when a definite buying habit has been established, the buying formula is:

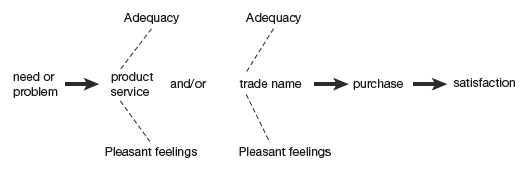

To ensure purchase, the product or service and the trade name (that is, the source of supply) must be considered adequate, and the buyer must experience a (pleasant) feeling of anticipated satisfaction when thinking of the product and/or service and the trade name. In many cases, an item viewed as adequate is also liked, and vice versa, but this is not always so. Some products and services that are quite adequate are not liked, and some things are liked and bought that are admittedly not as good as competing items. Similar reasoning applies to trade names. Some sources of supply are both adequate and liked, others are adequate but not liked, still others are liked but patronized even though they are inadequate compared to competing sources.

With adequacy and pleasant feelings included, the buying formula becomes

When a buying habit is being established, the buyer must know why the product or service is an adequate solution to the need or problem, and why the trade name is the best one to buy. The buyers also must have a pleasant feeling toward the product or service and the trade name.

Then, whenever the buyer’s buying habit is challenged by a friend’s remark, a competing salesperson’s presentation, or a competitor’s advertisement, the buyer needs reasons to defend the purchase, and, in addition, he or she needs a pleasant feeling toward both the product or service and the trade name. All this is represented by the dashed lines in the formula.

The primary elements in a well-established buying habit are those connected by solid lines, on the central line of the formula. Most purchases are made with scarcely a thought as to why, and with a minimum of feeling. And it should be the constant aim of the salesperson and advertiser to form such direct associations. Reasons (adequacy of solution) and pleasant feelings constitute the elements of defense in the buying habit. As long as they are present, repeat buying occurs.

The answer to each selling problem is implied in the buying formula, and differences among answers are differences in emphasis upon the elements in the formula.

Where the emphasis should be placed depends upon a variety of circumstances. Without going into detail, it may be said that

- If the prospect does not feel a need or is unable recognize a problem that can be satisfied by the product or service, the need or problem should be emphasized.

- If the prospect does not think of the product or service when he or she feels the need or recognizes the problem, the association between need or problem and product or service should be emphasized.

- If the prospect does not think of the trade name when he or she thinks of the product or service, the association between product or service and trade name should be emphasized.

- If need or problem, product or service, and trade name are well associated, emphasis should be put upon facilitating purchase and use.

- If competition is felt, emphasis should be put upon establishing in the prospects’ minds the adequacy of the trade-named product or service, and pleasant feelings toward it.

- If sales to new prospects are desired, every element in the formula should be presented.

- If more sales to old customers are desired, the latter should be reminded. (Developing new uses is comparable to selling to new customers.)

4. “Behavioral Equation” Theory

Using a stimulus-response model (a sophisticated version of the “right set of circumstances” theory), and incorporating findings from behavioral research, J.A. Howard explains buying behavior in terms of the purchasing decision process, viewed as phases of the learning process.

Four essential elements of the learning process included in the stimulus-response model are drive, cue, response, and reinforcement, described as follows:

- Drives are strong internal stimuli that impel the buyer’s response. There are two kinds:

- Innate drives stem from the physiological needs, such as hunger, thirst, pain, cold, and sex.

- Learned drives, such as striving for status or social approval, are acquired when paired with the satisfying of innate drives. They are elaborations of the innate drives, serving as a facade behind which the functioning of the innate drives is hidden. In so far as marketing is concerned, the learned drives are dominant in economically advanced societies.

- Cues are weak stimuli that determine when the buyer will respond.

- Triggering cues activate the decision process for any given purchase.

- Nontriggering cues influence the decision process but do not activate it, and may operate at any time even though the buyer is not contemplating a purchase. There are two kinds:

-

-

- Product cues are external stimuli received from the product directly, for example, color of the package, weight, or price.

- Informational cues are external stimuli that provide information of a symbolic nature about the product. Such stimuli may come from advertising, conversations with other people (including sales personnel), and so on.

- Specific product and information cues may also function as triggering cues. This may happen when price triggers the buyer’s decision.

-

3. Response is what the buyer does.

4. A reinforcement is any event that strengthens the buyer’s tendency to make a particular response.[6]

Howard incorporates these four elements into an equation:

B = P x D x K x V

where

B = response or the internal response tendency, that is, the act of purchasing a brand or patronizing a supplier

P = predisposition or the inward response tendency, that is, force of habit D = present drive level (amount of motivation)

K = “incentive potential,” that is, the value of the product or its potential satisfaction to the buyer

V = intensity of all cues: triggering, product, or informational

The relation among the variables is multiplicative. Thus, if any independent variable has a zero value, B will also be zero and there is no response. No matter how much P there may be, for example, if the individual is unmotivated (D = 0), there is no response.

Each time there is a response—a purchase—in which satisfaction (K) is sufficient to yield a reward, predisposition (P) increases in value. In other words, when the satisfaction yields a reward, reinforcement occurs, and, technically, what is reinforced is the tendency to make a response in the future to the cue that immediately preceded the rewarded response. After reinforcement, the probability increases that the buyer will buy the product (or patronize the supplier) the next time the cue appears—in other words, the buyer has learned.[7]

Buyer-seller dyad and reinforcement. In the interactions of a salesperson and a buyer, each can display a type of behavior that is rewarding, that is reinforcing, to the other. The salesperson provides the buyer with a product (and the necessary information about it and its uses) that the buyer needs; this satisfaction of the need is rewarding to the buyer, who, in turn, can reward the salesperson by buying the product. Each can also reward the other by providing social approval. The salesperson gives social approval to a buyer by displaying high regard with friendly greetings, warm conversation, praise, and the like.

In understanding the salesperson-client relation, it is helpful to separate economic aspects from social features. The salesperson wishes to sell a product, and the buyer wishes to buy it—these are the economic features. Each participant also places a value and cost upon the social features. Behavior concerning these features of the relationship consist of sentiments, or expressions of different degrees of liking or social approval. Salespersons attempt to receive rewards (reinforcements), either in sentiment or economic by changing their own behavior or getting buyers to change theirs.

Salesperson’s influence process. The process by which the salesperson influences the buyer is explainable in terms of the equation B = P x D x K x V The salesperson influences P (predisposition) directly, for example, through interacting with the buyer in ways rewarding to the buyer. The greatest effect on P, however, comes from using the product. The salesperson exerts influence through D (amount of motivation), this influence being strong when the buyer seeks information in terms of informational cues. If the ends to be served are not clearly defined, by helping to clarify these, the buyer’s goals, the salesperson again exerts influence through D. When the buyer has stopped learning—when the buyer’s buying behavior becomes automatic—the salesperson influences D by providing triggering cues. When the buyer has narrowed down the choices to a few sellers, the salesperson, by communicating the merits of the company brand, can cause it to appear relatively better, and thus affect K (its potential satisfaction for the buyer). Finally, the salesperson can vary the intensity of his or her effort, so making the difference in V (the intensity of all cues).[8]

Salesperson’s role in reducing buyer dissonance. According to Fest- inger’s theory of cognitive dissonance, when individuals choose between two or more alternatives, anxiety or dissonance will almost always occur because the decision has unattractive as well as attractive features. After decisions, people expose themselves to information that they perceive as likely to support their choices, and to avoid information likely to favor rejected alternatives.[9]

Although Festinger evidently meant his theory to apply only to postdecision anxiety, it seems reasonable that it should hold for predecision anxiety. Hauk, for instance, writes that a buyer may panic on reaching the point of decision and rush into the purchase as an escape from the problem or put it off because of the difficulty of deciding.[10] It seems, then, that a buyer can experience either predecision or postdecision dissonance, or both.

Reducing pre- and postdecision anxiety or dissonance is an important function of the salesperson. Recognizing that the buyer’s dissonance varies both according to whether the product is an established or a new one, and whether the salesperson-client relationship is ongoing or new, these are four types of cases involving the salesperson’s role.

- An established product—an ongoing salesperson-client relationship. Unless the market is unstable, the buyer tends toward automatic response behavior, in which no learning is involved and thus experiences little, if any, dissonance; but in so far as it does occur, the salesperson is effective because the salesperson is trusted by the buyer.

- An established product—a new salesperson-client relationship. The salesperson, being new, is less effective in reducing dissonance.

- A new product—an ongoing salesperson-client relationship. Unless the buyer generalizes from personal experience with an established similar product, the buyer experiences dissonance, especially if it is an important product. Because of the established relationship with the buyer, the salesperson can reduce dissonance.

- A new product—a new salesperson-client relationship. The buyer needs dissonance reduction, and the salesperson is less capable of providing it.[11]

How can a salesperson facilitate the buyer’s dissonance reduction? Two ways are (1) to emphasize the advantages of the product purchased, while stressing the disadvantages of the forgone alternatives, and (2) to show that many characteristics of the chosen item are similar to products the buyer has forgone, but which are approved by the reference groups.[12] In other words, the buyer experiencing cognitive dissonance needs reassuring that the decision is or was a wise one; the salesperson provides information that permits the buyer to rationalize the decision.

Source: Richard R. Still, Edward W. Cundliff, Normal A. P Govoni, Sandeep Puri (2017), Sales and Distribution Management: Decisions, Strategies, and Cases, Pearson; Sixth edition.

Wow! Thank you! I permanently wanted to write on my site something like that. Can I implement a fragment of your post to my blog?