Types of research can be looked at from three different perspectives (Figure 1.2):

- applications of the findings of the research study;

- objectives of the study;

- mode of enquiry used in conducting the study.

The classification of the types of a study on the basis of these perspectives is not mutually exclusive: that is, a research study classified from the viewpoint of ‘application’ can also be classified from the perspectives of ‘objectives’ and ‘enquiry mode’ employed. For example, a research project may be classified as pure or applied research (from the perspective of application), as descriptive, correlational, explanatory or exploratory (from the perspective of objectives) and as qualitative or quantitative (from the perspective of the enquiry mode employed).

1. Types of research: application perspective

If you examine a research endeavour from the perspective of its application, there are two broad categories: pure research and applied research. In the social sciences, according to Bailey (1978: 17):

Pure research involves developing and testing theories and hypotheses that are intellectually challenging to the researcher but may or may not have practical application at the present time or in the future. Thus such work often involves the testing of hypotheses containing very abstract and specialised concepts.

Pure research is also concerned with the development, examination, verification and refinement of research methods, procedures, techniques and tools that form the body of research methodology. Examples of pure research include developing a sampling technique that can be applied to a particular situation; developing a methodology to assess the validity of a procedure; developing an instrument, say, to measure the stress level in people; and finding the best way of measuring people’s attitudes. The knowledge produced through pure research is sought in order to add to the existing body of knowledge of research methods.

Most of the research in the social sciences is applied. In other words, the research techniques, procedures and methods that form the body of research methodology are applied to the collection of information about various aspects of a situation, issue, problem or phenomenon so that the information gathered can be used in other ways — such as for policy formulation, administration and the enhancement of understanding of a phenomenon.

2. Types of research: objectives perspective

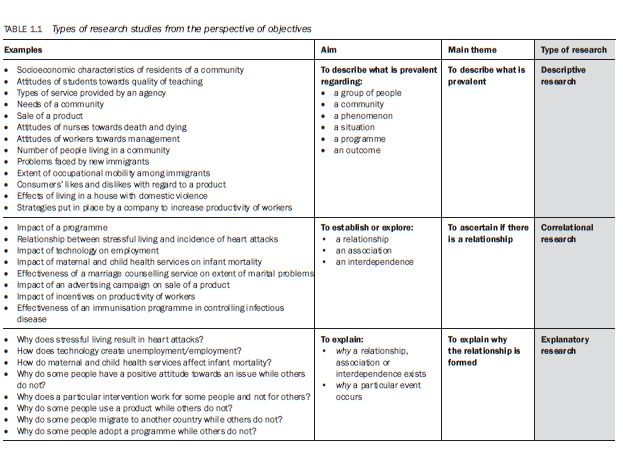

If you examine a research study from the perspective of its objectives, broadly a research endeavour can be classified as descriptive, correlational, explanatory or exploratory.

A research study classified as a descriptive study attempts to describe systematically a situation, problem, phenomenon, service or programme, or provides information about, say, the living conditions of a community, or describes attitudes towards an issue. For example, it may attempt to describe the types of service provided by an organisation, the administrative structure of an organisation, the living conditions of Aboriginal people in the outback, the needs of a community, what it means to go through a divorce, how a child feels living in a house with domestic violence, or the attitudes of employees towards management. The main purpose of such studies is to describe what is prevalent with respect to the issue/ problem under study.

The main emphasis in a correlational study is to discover or establish the existence of a relationship/association/interdependence between two or more aspects of a situation. What is the impact of an advertising campaign on the sale of a product? What is the relationship between stressful living and the incidence of heart attack? What is the relationship between fertility and mortality? What is the relationship between technology and unemployment? What is the effect of a health service on the control of a disease, or the home environment on educational achievement? These studies examine whether there is a relationship between two or more aspects of a situation or phenomenon and, therefore, are called correlational studies.

Explanatory research attempts to clarify why and how there is a relationship between two aspects of a situation or phenomenon. This type of research attempts to explain, for example, why stressful living results in heart attacks; why a decline in mortality is followed by a fertility decline; or how the home environment affects children’s level of academic achievement.

The fourth type of research, from the viewpoint of the objectives of a study, is called exploratory research. This is when a study is undertaken with the objective either to explore an area where little is known or to investigate the possibilities of undertaking a particular research study. When a study is carried out to determine its feasibility it is also called a feasibility study or a pilot study. It is usually carried out when a researcher wants to explore areas about which s/he has little or no knowledge. A small-scale study is undertaken to decide if it is worth carrying out a detailed investigation. On the basis of the assessment made during the exploratory study, a full study may eventuate. Exploratory studies are also conducted to develop, refine and/or test measurement tools and procedures. Table 1.1 shows the types of research study from the viewpoint of objectives.

Although, theoretically, a research study can be classified in one of the above objectives— perspective categories, in practice, most studies are a combination of the first three; that is, they contain elements of descriptive, correlational and explanatory research. In this book the guidelines suggested for writing a research report encourage you to integrate these aspects.

3. Types of research: mode of enquiry perspective

The third perspective in our typology of research concerns the process you adopt to find answers to your research questions. Broadly, there are two approaches to enquiry:

- the structured approach;

- the unstructured

In the structured approach everything that forms the research process — objectives, design, sample, and the questions that you plan to ask of respondents — is predetermined. The unstructured approach, by contrast, allows flexibility in all these aspects of the process. The structured approach is more appropriate to determine the extent of a problem, issue or phenomenon, whereas the unstructured approach is predominantly used to explore its nature, in other words, variation/diversity per se in a phenomenon, issue, problem or attitude towards an issue. For example, if you want to research the different perspectives of an issue, the problems experienced by people living in a community or the different views people hold towards an issue, then these are better explored using unstructured enquiries. On the other hand, to find out how many people have a particular perspective, how many people have a particular problem, or how many people hold a particular view, you need to have a structured approach to enquiry. Before undertaking a structured enquiry, in the author’s opinion, an unstructured enquiry must be undertaken to ascertain the diversity in a phenomenon which can then be quantified through the structured enquiry. Both approaches have their place in research. Both have their strengths and weaknesses. Therefore, you should not ‘lock’ yourself solely into a structured or unstructured approach.

The structured approach to enquiry is usually classified as quantitative research and unstructured as qualitative research. Other distinctions between quantitative and qualitative research are outlined in Table 2.1 in Chapter 2. The choice between quantitative and qualitative approaches (or structured or unstructured) should depend upon:

- Aim of your enquiry – exploration, confirmation or quantification.

- Use of the findings – policy formulation or process understanding.

The distinction between quantitative and qualitative research, in addition to the structured/ unstructured process of enquiry, is also dependent upon some other considerations which are briefly presented in Table 2.1.

A study is classified as qualitative if the purpose of the study is primarily to describe a situation, phenomenon, problem or event; if the information is gathered through the use of variables measured on nominal or ordinal scales (qualitative measurement scales); and if the analysis is done to establish the variation in the situation, phenomenon or problem without quantifying it. The description of an observed situation, the historical enumeration of events, an account of the different opinions people have about an issue, and a description of the living conditions of a community are examples of qualitative research.

On the other hand, the study is classified as quantitative if you want to quantify the variation in a phenomenon, situation, problem or issue; if information is gathered using predominantly quantitative variables; and if the analysis is geared to ascertain the magnitude of the variation. Examples of quantitative aspects of a research study are: How many people have a particular problem? How many people hold a particular attitude?

The use of statistics is not an integral part of a quantitative study. The main function of statistics is to act as a test to confirm or contradict the conclusions that you have drawn on the basis of your understanding of analysed data. Statistics, among other things, help you to quantify the magnitude of an association or relationship, provide an indication of the confidence you can place in your findings and help you to isolate the effect of different variables.

It is strongly recommended that you do not ‘lock yourself’ into becoming either solely a quantitative or solely a qualitative researcher. It is true that there are disciplines that lend themselves predominantly either to qualitative or to quantitative research. For example, such disciplines as anthropology, history and sociology are more inclined towards qualitative research, whereas psychology, epidemiology, education, economics, public health and marketing are more inclined towards quantitative research. However, this does not mean that an economist or a psychologist never uses the qualitative approach, or that an anthropologist never uses quantitative information. There is increasing recognition by most disciplines in the social sciences that both types of research are important for a good research study. The research problem itself should determine whether the study is carried out using quantitative or qualitative methodologies.

As both qualitative and quantitative approaches have their strengths and weaknesses, and advantages and disadvantages, ‘neither one is markedly superior to the other in all respects’ (Ackroyd & Hughes 1992: 30). The measurement and analysis of the variables about which information is obtained in a research study are dependent upon the purpose of the study. In many studies you need to combine both qualitative and quantitative approaches. For example, suppose you want to find out the types of service available to victims of domestic violence in a city and the extent of their utilisation. Types of service is the qualitative aspect of the study as finding out about them entails description of the services. The extent of utilisation of the services is the quantitative aspect as it involves estimating the number of people who use the services and calculating other indicators that reflect the extent of utilisation.

Source: Kumar Ranjit (2012), Research methodology: a step-by-step guide for beginners, SAGE Publications Ltd; Third edition.

29 Jul 2021

10 Aug 2019

29 Jul 2021

30 Jul 2021

29 Jul 2021

30 Jul 2021