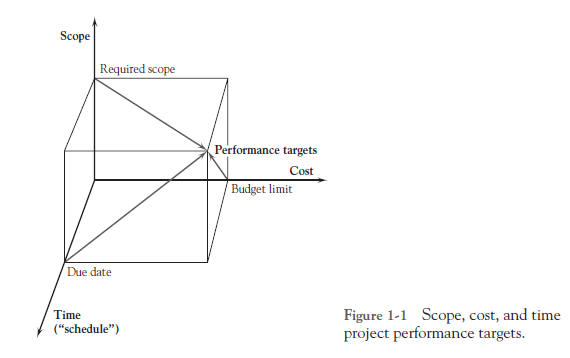

The performance of a project, commonly called its “efficiency,” is assessed on the basis of three criteria, variously known as the “triple constraints,” the “iron triangle,” the “golden constraints,” and so on. Is the project on time or early? Is the project on or under budget? Does the project deliver the scope to the agreed-upon specification? Figure 1-1 shows the three goals of a project specifications. The performance of the project and the PM is measured by the degree to which these goals are achieved. A recent issue, however, has arisen: meeting a project’s triple constraints often does not achieve the aims of the project for the client, known as the project’s “effectiveness;” that is, the project didn’t deliver the benefits the client was hoping to gain. However, not meeting the project’s triple constraint usually dooms the project to failure. This issue is discussed further in Section 1.5.

One of these goals, the project’s specifications or “scope,” is set primarily by the client (although the client agrees to all three when contracting for the project). It is the client who must decide what capabilities are required of the project’s deliverables—and this is what makes the project unique. Some writers insist that “quality” is a separate and distinct goal of the project along with time, cost, and scope. We do not agree because we consider quality an inherent part of the project scope.

If we did not live in an uncertain world in which best made plans often go awry, managing projects would be relatively simple, requiring only careful planning. Unfortunately, we do not live in a predictable (deterministic) world, but one characterized by chance events (uncertainty). This ensures that projects travel a rough road. Murphy’s law seems as universal as death and taxes, and the result is that the most skilled planning is upset by uncertainty. Thus, the PM spends a great deal of time adapting to unpredicted change. The primary method of adapting is to trade off one objective for another. If a construction project falls behind schedule because of bad weather, it may be possible to get back on schedule by adding resources—in this case, probably labor using overtime and perhaps some additional equipment. If the budget cannot be raised to cover the additional resources, the PM may have to negotiate with the client for a later delivery date of the building. If neither cost nor schedule can be negotiated, the client may be willing to cut back on some of the features in the building in order to allow the project to finish on time and budget (e.g., substituting carpet for tile in some of the spaces). As a final alternative, the contractor may have to “swallow” the added costs (or pay a penalty for late delivery) and accept lower profits.

This example illustrates a fundamental point. Namely, managing the trade-offs among the three project goals is in fact one of the primary roles of the project manager. Furthermore, managing these trade-offs in the most effective manner requires that the project manager have a clear understanding of how the project supports broader organizational goals. Thus, the organization’s overall strategy is the most important consideration for managing the trade-offs that will be required among the three project goals.

All projects are always carried out under conditions of uncertainty. Well-tested software routines may not perform properly when integrated with other well-tested routines. A chemical compound may destroy cancer cells in a test tube—and even in the bodies of test animals—but may kill the host as well as the cancer. Where one cannot find an acceptable way to deal with a problem, the only alternative may be to stop the project and start afresh to achieve the desired deliverables.

As we note throughout this book, projects are all about uncertainty. Therefore, in addition to effectively managing trade-offs, the second major role of the project manager is dealing with uncertainty, that is, managing risks. The time required to complete a project, the availability and costs of key resources, the timing of solutions to technological problems, a wide variety of macroeconomic variables, the whims of a client, the actions taken by competitors, even the likelihood that the output of a project will perform as expected, all these exemplify the uncertainties encountered when managing projects. While there are actions that may be taken to reduce the uncertainty, no actions of a PM can ever eliminate it.

As Hatfield (2008) points out, projects are complex and include interfaces, interdependencies, and many assumptions, any or all of which may turn out to be wrong. Also, projects are managed by people, which adds to the uncertainty. Gale (2008a) reminds us that the uncertainties include everything from legislation that can change how we do business, to earthquakes and other “acts of God.” Therefore, in today’s turbulent business environment, effective decision making is predicated on an ability to manage the ambiguity that arises while we operate in a world characterized by uncertain information. (Risk management is discussed in Chapter 11 of the PMBOK, 5th ed., 2013.)

The first step in managing risk is to identify these potentially uncertain events and the likelihood that any or all may occur. This is called risk analysis. Different managers and organizations approach this problem in different ways. Gale advises expecting the unexpected; some managers suggest considering those things that keep one awake at night. Many organizations keep formal lists, a “risk register,” and use their Project Management Office (PMO, discussed in Chapter 2) to maintain and update the list of risks and approaches that have been successful in the past in dealing with specific risks. This information is then incorporated into the firm’s business-continuity and disaster- recovery plans. Every organization should have a well-defined process for dealing with risk, and we will discuss this issue at greater length in Section 3.5. At this point we simply overview risk analysis.

The essence of risk analysis is to make estimates or assumptions about the probability distributions associated with key parameters and variables and to use analytic decision models or Monte Carlo simulation models based on these distributions to evaluate the desirability of certain managerial decisions. Real-world problems are usually large enough that the use of analytic models is very difficult and time consuming. With modern computer software, simulation is not difficult.

A mathematical model of the situation is constructed that models the relationship between unknown input variables and important outcomes. The model is run (or replicated) repeatedly, starting from a different point each time based on random choices of values from the probability distributions of the input variables. Outputs of the model are used to construct statistical distributions of outcomes of interest to decision makers, such as costs, profits, completion dates, or return on investment. These distributions are the risk profiles of the outcomes associated with a decision. Risk profiles can be analyzed by the manager when considering a decision, along with many other factors such as strategic concerns, behavioral issues, fit with the organization, cost and scheduling issues, and so on.

Thus in this book, we adopt the point of view that the two primary roles of the project manager are managing trade-offs and managing risks. Because these two roles are fundamental to the work of the project manager, icons are displayed throughout the book in the left margin when these topics are discussed. It is also important to point out that these two roles are highly integrated with one another. Indeed, managing risk is actually tightly coupled with managing the three traditional goals of project management. For example, the more uncertainty the project manager faces, the greater the risk that the project will go over budget, finish late, and/or not meet its original scope. However, beyond these rather obvious relationships, there is also a more subtle connection. In particular, project risk can actually be thought of as a fourth trade-off opportunity at the project manager’s disposal. For example, the project’s budget can be increased in order to collect additional data that in turn will reduce the uncertainty related to how long it will take to complete the project. Likewise, the project’s deadline can be reduced, but this will increase the uncertainty about whether it will be completed on time.

Most of the trade-offs PMs make are reasonably straightforward if the organization’s strategy is well understood and trade-offs are discussed during the planning, budgeting, and scheduling phases of the project. Usually they involve trading time and cost, but if we cannot alter either the schedule or the budget, the scope of the project may be altered or additional risk accepted. Frills on the finished product may be foregone, capabilities not badly needed may be compromised. From the early stages of the project, it is the PM’s duty to know which elements of project performance are sacrosanct.

One final comment on this subject: Projects must have some flexibility. Again, this is because we do not live in a deterministic world. Occasionally, a senior manager (who does not have to manage the project) presents the PM with a document precisely listing a set of deliverables, a fixed budget, and a firm schedule. This is failure in the making for the PM. Unless the budget is overly generous, the schedule overlong, and the deliverables easily accomplished, the system is, as mathematicians say, “overdetermined.” If Mother Nature so much as hiccups, the project will fail to meet its rigid parameters. A PM cannot be successful without flexibility to manage the trade-offs.

Source: Meredith Jack R., Mantel Jr. Samuel J., Shafer Scott M., Sutton Margaret M. (2017), Project Management in Practice, John Wiley & Sons, Inc. 3th Edition.

8 Jun 2021

8 Jun 2021

8 Jun 2021

8 Jun 2021

8 Jun 2021

9 Jun 2021