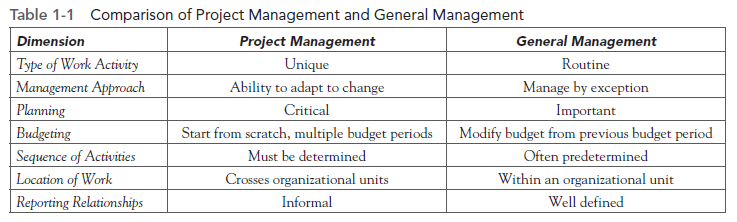

As is shown in Table 1-1, project management differs from general management largely because projects differ from what we have referred to as “nonprojects.” The naturally high level of conflict present in projects means that the project manager (PM) must have special skills in conflict resolution. The fact that projects are unique means that the PM must be creative and flexible, and have the ability to adjust rapidly to changes. When managing nonprojects, the general manager tries to “manage by exception.” In other words, for nonprojects almost everything is routine and is handled routinely by subordinates. The manager deals only with the exceptions. For the PM, almost everything is an exception.

1. Major Differences

Certainly, general management’s success is dependent on good planning. For projects, however, planning is much more carefully detailed and project success is absolutely dependent on such planning. The project plan is the result of integrating all information about a project’s deliverables, generally referred to as the “scope” of the project, and its targeted date of completion. “Scope” has two meanings. One is “product scope,” which defines the performance requirements of a project, and “project scope,” which details the work required to deliver the product scope (see Chapter 5, p. 105 of PMBOK, 2013). To avoid confusion, we will use the term scope to mean “product scope” and will allow the work, resources, and time needed by the project to deliver the product scope to the customer to be defined by the project’s plan (discussed in detail in Chapter 3). Therefore, the scope and due date of the project determine its plan, that is, its budget, schedule, control, and evaluation. Detailed planning is critically important. One should not, of course, take so much time planning that nothing ever gets done, but careful planning is a major contributor to project success. Project planning is discussed in Chapter 3 and is amplified throughout the rest of this book.

Project budgeting differs from standard budgeting, not in accounting techniques, but in the way budgets are constructed. Budgets for nonprojects are primarily modifications of budgets for the same activity in the previous period. Project budgets are newly created for each project and often cover several “budget periods” in the future. The project budget is derived directly from the project plan that calls for specific activities. These activities require resources, and such resources are the heart of the project budget. Similarly, the project schedule is also derived from the project plan.

In a nonproject manufacturing line, the sequence in which various things are done is set when the production line is designed. The sequence of activities often is not altered when new models are produced. On the other hand, each project has a schedule of its own. Previous projects with deliverables similar to the one at hand may provide a rough template for the current project, but its specific schedule will be determined by the time required for a specific set of resources to do the specific work that must be done to achieve each project’s specific scope by the specific date on which the project is due for delivery to the client. As we will see in later chapters, the special requirements associated with projects have led to the creation of special managerial tools for budgeting and scheduling.

The routine work of most organizations takes place within a well-defined structure of divisions, departments, areas, and similar subdivisions of the total enterprise. The typical project cannot thrive under such restrictions. The need for technical knowledge, information, and special skills almost always requires that departmental lines be crossed. This is simply another way of describing the multidisciplinary character of projects. When projects are conducted side-by-side with routine activities, chaos tends to result—the nonprojects rarely crossing organizational boundaries and the projects crossing them freely. These problems and recommended actions are discussed at greater length in Chapter 2.

Even when large firms establish manufacturing plants or distribution centers in different countries, a management team is established on site. For projects, “globalization” has a different meaning. Individual members of project teams may be spread across countries, continents, and oceans, and speak several different languages. Some project team members may never even have a face-to-face meeting with the project manager, though transcontinental and intercontinental video meetings combining telephone and computer are common.

The discussion of structure leads to consideration of another difference between project and general management. In general management, there are reasonably well- defined reporting relationships. Superior-subordinate relationships are known, and lines of authority are clear. In project management this is rarely true. The PM may be relatively low in the hierarchical chain of command. This does not, however, reduce his or her responsibility of completing a project successfully. Responsibility without the authority of rank or position is so common in project management as to be the rule, not the exception.

2. Negotiation

With little legitimate authority, the PM depends on negotiation skills to gain the cooperation of the many departments in the organization that may be asked to supply technology, information, resources, and personnel to the project. The parent organization’s standard departments have their own objectives, priorities, and personnel. The project is not their responsibility, and the project tends to get the leftovers, if any, after the departments have satisfied their own need for resources. Without any real command authority, the PM must negotiate for almost everything the project needs.

It is important to note that there are three different types of negotiation, win-win negotiation, win-lose negotiation, and lose-lose negotiation. When you negotiate the purchase of a car or a home, you are usually engaging in win-lose negotiation. The less you pay for a home or car, the less profit the seller makes. Your savings are the other party’s losses—win-lose negotiation. This type of negotiation is never appropriate when dealing with other members of your organization. If you manage to “defeat” a department head and get resources or commitments that the department head did not wish to give you, imagine what will happen the next time you need something from this individual. The PM simply cannot risk win-lose situations when negotiating with other members of the organization.

Lose-lose negotiation occurs when one party is unwilling to assert his or her position aggressively while at the same time resists cooperating with the other party. This often occurs in situations where one or both of the parties are conflict avoiders. When one party is not willing to help the other party achieve his or her objective and at the same time is unwilling to pursue his or her own objectives, the end result is that both parties lose.

Within the organization, win-win negotiation is mandatory. In essence, in win-win negotiation both parties must try to understand what the other party needs. The problem you face as a negotiator is how to help other parties meet their needs in return for their help in meeting the needs of your project. When negotiation takes place repeatedly between the same individuals, win-win negotiation is the only sensible procedure. PMs spend a great deal of their time negotiating. General managers spend relatively little. Skill at win-win negotiating is a requirement for successful project managing (see Fisher and Ury, 1983; Jandt, 1987; and Raiffa, 1982).

One final point about negotiating: Successful win-win negotiation often involves taking a synergistic approach by searching for the “third alternative.” For example, consider a product development project focusing on the development of a new printer. A design engineer working on the project suggests adding more memory to the printer. The PM initially opposes this suggestion, feeling that the added memory will make the printer too costly. Rather than rejecting the suggestion, however, the PM tries to gain a better understanding of the design engineer’s concern.

Based on their discussion, the PM learns that the engineer’s purpose in requesting additional memory is to increase the printer’s speed. After benchmarking the competition, the design engineer feels the printer will not be competitive as it is currently configured. The PM explains his fear that adding the extra memory will increase the cost of the printer to the point that it also will no longer be cost competitive. Based on this discussion the design engineer and PM agree that they need to search for another (third) alternative that will increase the printer’s speed without increasing its costs. A couple of days later, the design engineer identifies a new ink that can simultaneously increase the printer’s speed and actually lower its total and operating costs.

Project management differs greatly from general management. Every project is planned, budgeted, scheduled, and controlled as a unique task. Unlike nonprojects, projects are often multidisciplinary and usually have considerable need to cross departmental boundaries for technology, information, resources, and personnel. Crossing these boundaries tends to lead to intergroup conflict. The development of a detailed project plan based on the scope and due date of the project is critical to the project’s success.

Unlike their general management counterparts, project managers have responsibility for accomplishing a project, but little or no legitimate authority to command the required resources from the functional departments. The PM must be skilled at win-win negotiation to obtain these resources.

Source: Meredith Jack R., Mantel Jr. Samuel J., Shafer Scott M., Sutton Margaret M. (2017), Project Management in Practice, John Wiley & Sons, Inc. 3th Edition.

It’s amazing designed for me to have a site, which is good in support

of my experience. thanks admin

Thanks in favor of sharing such a nice opinion, article is fastidious,

thats why i have read it completely

What’s up to all, how is everything, I think every one is getting more from this website, and your views are pleasant in favor of new visitors.

Very nice post. I just stumbled upon your weblog and wanted to say that I’ve

really enjoyed surfing around your blog posts. In any case I

will be subscribing to your rss feed and I hope you

write again soon!

I think the admin of this website is actually working hard in favor of his site, as here every data is quality based material.