1. Cooperation among Competitors

Fierce competitors for decades, Apple and IBM recently formed an alliance to cooperate in developing apps and selling iPhones and iPads. For Apple, the alliance allows the company to expand the reach of its products into the business world, whereas for IBM the alliance allows the firm to move more of its business software onto mobile devices. In a joint interview with IBM CEO Virginia Rometty, Apple’s CEO Tim Cook observed, “In 1984, we were competitors, but today, I don’t think you can find two more complementary companies.” Apple and IBM are today developing more than 100 apps together.

Also fierce competitors for decades, Apple and Google recently agreed to share rights to digital content with any consumer who buys a Disney movie using the Disney Movies Anywhere app. Previously, both Apple and Google had restricted movies, TV shows, and other content to its own family of iOS or Android-powered devices, respectively. Now, both Apple and Google pay Walt Disney Company a wholesale rate for each copy of a Disney film that they sell, regardless of the type device people use.

Strategies that stress cooperation among competitors are being used more. For collaboration between competitors to succeed, both firms must contribute something distinctive, such as technology, distribution, basic research, or manufacturing capacity. But a major risk is that unintended transfers of important skills or technology may occur at organizational levels below where the deal was signed. Information not covered in the formal agreement often gets traded in the day-to-day interactions and dealings of engineers, marketers, and product developers. Firms often give away too much information to rival firms when operating under cooperative agreements! Tighter formal agreements are needed.

Perhaps the best example of rival firms in an industry forming alliances to compete against each other is the airline industry. Today, there are three major alliances: Star, SkyTeam, and Oneworld. Joint ventures and cooperative arrangements among competitors demand a certain amount of trust if companies are to combat paranoia about whether one firm will injure the other. Increasing numbers of domestic firms are joining forces with competitive foreign firms to reap mutual benefits. Kathryn Harrigan at Columbia University contends, “Within a decade, most companies will be members of teams that compete against each other.”

Often, U.S. companies enter alliances primarily to avoid investments, being more interested in reducing the costs and risks of entering new businesses or markets than in acquiring new skills. In contrast, learning from the partner is a major reason why Asian and European firms enter into cooperative agreements. American firms, too, should place learning high on the list of reasons to be cooperative with competitors. Companies in the United States often form alliances with Asian firms to gain an understanding of their manufacturing excellence, but Asian competence in this area is not easily transferable. Manufacturing excellence is a complex system that includes employee training and involvement, integration with suppliers, statistical process controls, value engineering, and design. In contrast, U.S. know-how in technology and related areas can be imitated more easily. Therefore, U.S. firms need to be careful not to give away more intelligence than they receive in cooperative agreements with rival Asian firms.

Academic Research Capsule 5-1 examines whether international alliances are more effective with competitors or noncompetitors.

2. Joint Venture and Partnering

Joint venture is a popular strategy that occurs when two or more companies form a temporary partnership or consortium for the purpose of capitalizing on some opportunity. Often, the two or more sponsoring firms form a separate organization and have shared equity ownership in the new entity.

Other types of cooperative arrangements include research and development partnerships, crossdistribution agreements, cross-licensing agreements, cross-manufacturing agreements, and jointbidding consortia. Although joint ventures and partnerships are increasingly preferred over mergers as a means for achieving strategies, they are not always successful, for four primary reasons:

- Managers who must collaborate daily in operating the venture are not involved in forming or shaping the venture.

- The venture may benefit the partnering companies but may not benefit customers, who then complain about poorer service or criticize the companies in other ways.

- The venture may not be supported equally by both partners. If supported unequally, problems arise.

- The venture may begin to compete more with one of the partners than the other.24

Joint ventures are being used increasingly because they allow companies to improve communications and networking, to globalize operations, and to minimize risk. They are formed when a given opportunity is too complex, uneconomical, or risky for a single firm to pursue alone, or when an endeavor requires a broader range of competencies and know-how than any one firm can marshal. Kathryn Rudie Harrigan, summarizes the trend toward increased joint venturing:

In today’s global business environment of scarce resources, rapid rates of technological change, and rising capital requirements, the important question is no longer “Shall we form a joint venture?” Now the question is “Which joint ventures and cooperative arrangements are most appropriate for our needs and expectations?” followed by “How do we manage these ventures most effectively?”25

In a global market tied together by the Internet, joint ventures, partnerships, and alliances are proving to be a more effective way to enhance corporate growth than mergers and acquisi- tions.26 Strategic partnering takes many forms, including outsourcing, information sharing, joint marketing, and joint research and development. There are today more than 10,000 joint ventures formed annually—more than all mergers and acquisitions. Walmart’s successful joint venture with Mexico’s Cifra is indicative of how a domestic firm can benefit immensely by partnering with a foreign company to gain substantial presence in that new country. Technology also is a major reason behind the need to form strategic alliances, with the Internet linking widely dispersed partners. For example, IBM recently signed partnerships with both Twitter and Facebook, enabling IBM to mine information from Twitter’s 302 million monthly active users and Facebook’s 1.4 billion users. With data from those partnerships, IBM is using its cloud analytics and data analytics services to help companies create social data-enabled apps. The leading data analytics, or business analytics, company is Tableau Software, followed by Qlik Technologies.

Although evidence is mounting that firms should use partnering as a means for achieving strategies, most U.S. firms in many industries—such as financial services, forest products, metals, and retailing—still operate in a merge or acquire mode to obtain growth. Partnering is not yet taught at most business schools and is often viewed within companies as a financial issue rather than a strategic issue. However, partnering has become a core competency, a strategic issue of such high importance.

Six guidelines for when a joint venture may be an especially effective means for pursuing strategies are:

- A privately owned organization is forming a joint venture with a publicly owned organization. There are some advantages to being privately held, such as closed ownership. There are also some advantages of being publicly held, such as access to stock issuances as a source of capital. Sometimes the unique advantages of being privately and publicly held can be synergistically combined in a joint venture.

- A domestic organization is forming a joint venture with a foreign company. A joint venture can provide a domestic company with the opportunity for obtaining local management in a foreign country, thereby reducing risks such as expropriation and harassment by host country officials.

- The distinct competencies of two or more firms complement each other especially well.

- Some project is potentially profitable but requires overwhelming resources and risks.

- Two or more smaller firms have trouble competing with a large firm.

- There is a need to quickly introduce a new technology.

3. Are International Alliances More Effective with Competitors or Noncompetitors?

Recent research reveals that small- and medium-size firms expanding into other countries should form alliances with noncompetitors rather than with rival firms. Alliances with competitors are more costly, directly and indirectly, and provide redundant knowledge and resources, leading researchers to conclude that small- and medium- size firms should strive to form alliances with noncompetitors rather than competitors whenever possible. Researchers report that the benefits of allying with competitors are offset by higher monitoring and control costs. Also, competing firms oftentimes share less knowledge than they could or should. Even though small- and medium-size firms typically have resource constraints as they expand globally and need alliances to grow, research shows that alliances with noncompetitors are positively associated with international performance, whereas alliances with competitors are negatively related. These findings are based on a recent study involving 162 British and U.S. private small- and medium-sized businesses.

Source: Based on K. Brouthers & P. Dimitratos, “International Alliances with Competitors and Non-Competitors: The Disparate Impact on SME International Performance,” Strategic Entrepreneurship Journal, 8, no. 2 (June 2014): 167-182.

4. Merger/Acquisition

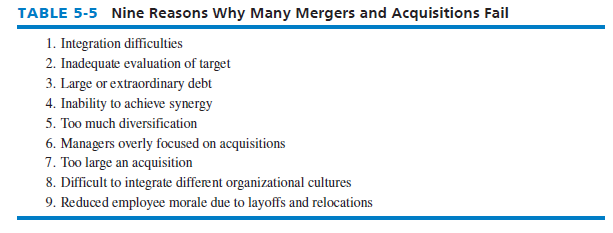

Merger and acquisition are two commonly used ways to pursue strategies. A merger occurs when two organizations of about equal size unite to form one enterprise. An acquisition occurs when a large organization purchases (acquires) a smaller firm or vice versa. If a merger or acquisition is not desired by both parties, it is called a hostile takeover, as opposed to a friendly merger. Most mergers are friendly, but the number of hostile takeovers is on the rise. Not all mergers are effective and successful. For example, soon after Halliburton acquired Baker Hughes, Halliburton’s stock price declined 11 percent. So, a merger between two firms can yield great benefits, but the price and reasoning must be right. Some key reasons why many mergers and acquisitions fail are provided in Table 5-5.

There were far more global mergers and acquisitions in 2014 than in any year since 2007, exceeding $3.5 billion. Three contributory reasons for this trend are (1) the desire of diversified firms to “spin off’ segments into separate companies that are then acquired by other firms, (2) the desire of firms to acquire similar companies in countries with low corporate tax rates and to shift company profits from the United States through those countries, and (3) the desire of shareholders for firms to continually grow revenues. Often, growth is most effective through acquisition, as opposed to internal (organic) growth.

In the United States, mergers and acquisitions totaled $1.52 trillion in 2014, comprising 45 percent of global deals, up from $998 billion, or 43 percent, the prior year. The data firm Dealogic reported in mid-2015 that global mergers and acquisitions in 2015 likely will hit an all-time record of $4.58 trillion.

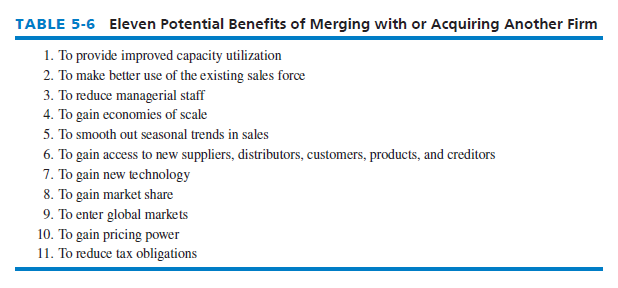

However, the U.S. Treasury Department’s new rules cracking down on tax inversions, where a company acquires a foreign company in order to avoid paying federal taxes, will likely somewhat curtail the number of mergers and acquisitions going forward. More than 10,000 mergers transpire annually in the United States, with same-industry combinations predominating. A general market consolidation is occurring in many industries, especially energy, banking, insurance, defense, and health care, but also in pharmaceuticals, food, airlines, accounting, publishing, computers, retailing, financial services, and biotechnology. Table 5-6 presents the potential benefits of merging with or acquiring another firm.

A leveraged buyout (LBO) occurs when a corporation’s shareholders are bought (hence buyout) by the company’s management and other private investors using borrowed funds (hence leverage). Besides trying to avoid a hostile takeover, other reasons for initiating an LBO include whenever a particular division(s) does not fit into an overall corporate strategy, or whenever selling a division could raise needed cash. An LBO converts a public firm into a private company.

5. Private-Equity Acquisitions

Private equity (PE) firms are acquiring and taking private a wide variety of companies almost daily in the business world. For example, one of the world’s largest private-equity firms, Apollo Global Management LLC, recently acquired 577 Chuck E. Cheese stores, the party pizza and arcade game venues, in 47 states and 10 foreign countries or territories. Apollo paid about $950 million for the parent company, CEC Entertainment, or a 12 percent premium over the company’s stock price. Chuck E. Cheese’s profit and revenue has been on the decline of late and the number of birthday parties hosted falling. Another large PE firm, Carlyle Group LP, recently acquired Johnson & Johnson’s blood-testing business for $4.15 billion.

Private equity firms are an integral part of the business world, especially in the United States but also in Europe, Asia, and, more recently, Latin America. Private equity firms such as Kohlberg Kravis Roberts (KKR) have jumped aggressively back into the business of acquiring and selling firms, and releasing new initial public offerings (IPO). A large PE firm, Cerberus Capital Management, recently bought the second-largest U.S. grocery store chain, Safeway Inc., based in Pleasanton, California, for $9.4 billion. Cerberus already owns Albertsons, the fifth-largest U.S. grocery store chain. Cerberus plans to unite the two companies’ distribution and purchasing operations to save money and compete better with major rivals, Wal-Mart Stores and Kroger.

Headquartered in Phoenix, Arizona, PetSmart was acquired in December 2014 by London- based PE firm BC Partners for $8.8 billion, the largest U.S. private equity deal of the year. PetSmart reportedly had received a joint bid offer from KKR and Clayton Dubilier & Rice, and a bid from Apollo, all PE firms. PetSmart operates 1,387 retail pet stores in the United States, Canada, and Puerto Rico. BC Partners paid $83 per share for PetSmart, a 6.86 percent premium over PetSmart’s closing stock price.

The intent of virtually all PE acquisitions is to buy firms at a low price and sell them later at a high price, arguably just good business. Private equity firms also are buying companies from other PE firms, such as Clayton, Dubilier & Rice’s recent purchase of David’s Bridal from Leonard Green & Partners LP for $1.05 billion. Such PE-to-PE acquisitions are called secondary buyouts. In addition, PE firms especially, but other firms too, sometimes borrow money simply to fund dividend payouts to themselves, a controversial practice known as dividend recapitalizations. Critics say dividend recapitalization saddles a company with debt, thus burdening its operations.

Source: David Fred, David Forest (2016), Strategic Management: A Competitive Advantage Approach, Concepts and Cases, Pearson (16th Edition).

18 May 2021

17 May 2021

17 May 2021

18 May 2021

18 May 2021

17 May 2021