1. Tax Rates

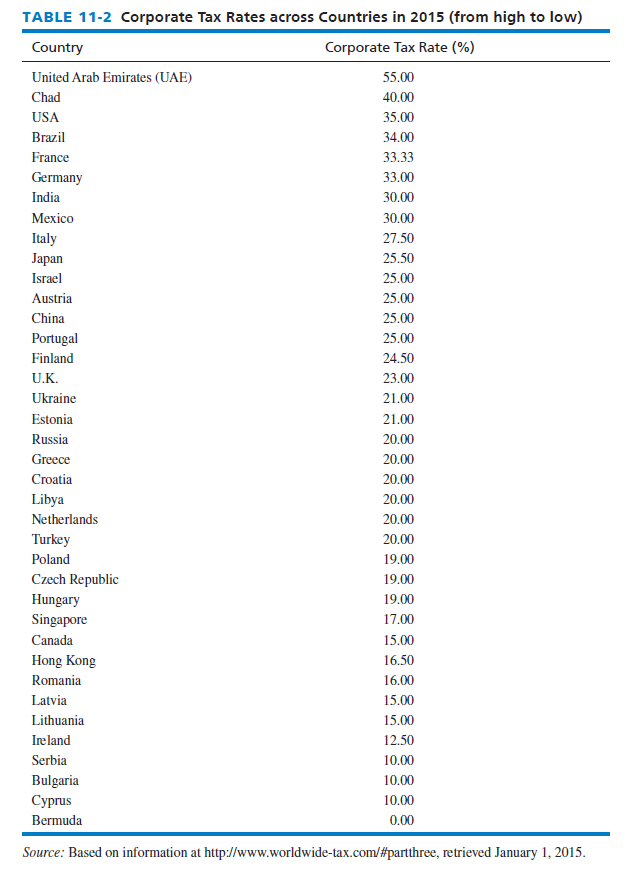

Tax rates in countries are important in strategic decisions regarding where to build manufacturing facilities or retail stores or even where to acquire other firms. High corporate tax rates deter investment in new factories and also provide strong incentives for corporations to avoid and evade taxes. Corporate tax rates vary considerably across countries and companies. As indicated in Table 11-2, the top national statutory corporate tax rates in 2015 among sample countries ranged from 0 percent in Bermuda to 55 percent in the United Arab Emirates (UAE). Note that some countries have a flat tax, which often, on adoption, triggers a surge in foreign direct investment. Signet Jewelers Ltd., owner of Kay’s Jewelers, Zale Corporation, and Jared the Galleria of Jewelry, is headquartered in Bermuda for a reason: zero corporate taxes.

The United States requires companies to pay the difference between lower foreign taxes and the U.S. corporate-tax rate of 35 percent when they bring their international earnings home. In contrast, the territorial system that many other countries use allows companies to pay little to no taxes on foreign profits above what they have already paid abroad. The United States is the only nation that imposes taxes on foreign earnings. Thus, to avoid paying U.S. taxes on income made in other countries, many U.S. companies are cash-rich outside the USA, but cash-poor inside the USA, and they bring cash back to the United States only as needed. For example, Microsoft has $15+ billion in cash reserves on its balance sheet, but only about 15 percent of that money is housed in the United States. General Electric and Apple have a similar policy to avoid paying U.S. corporate taxes. Emerson Electric has $2 billion in cash with almost all of it in Europe and Asia, so the firm borrows money in the United States rather than bringing its cash back and paying a 35 percent corporate U.S. tax on corporate profits minus whatever tax it has already paid overseas. Johnson & Johnson keeps virtually all of its $24+ billion in cash outside the United States, as does Illinois Tool Works Inc. Whirlpool has 85 percent of its cash offshore. Bruce Nolop, former CFO of Pitney Bowes, explains it this way: “You end up with the really peculiar result where you are borrowing money in the USA, while you show cash on the balance sheet that is trapped overseas. It is a totally inefficient capital structure.” The U.S. tax system, unfortunately for Americans, is structured so that companies can cut their tax bill by shifting income offshore to lower-tax countries.

Since the 1980s, most countries have been steadily lowering their tax rates, but the United States has not cut its top statutory corporate tax rate since 1993. Canada recently achieved its goal of having the most business-friendly tax system of the Group of Seven (G-7) nations, which include Canada, France, Germany, Italy, Japan, the United Kingdom and the United States. In January 2014, Canada’s federal corporate tax rate automatically fell to 15 percent from 16.5 percent as the last installment of a series of corporate rate cuts launched in 2006 by the administration of Prime Minister Stephen Harper, who had campaigned on the promise to lower Canada’s overall federal corporate tax rate by one third. More recently, the United Kingdom lowered its federal tax rate to 23 percent.

Other factors besides the corporate tax rate obviously affect companies’ decisions of where to locate plants and facilities and whether to acquire other firms. For example, the large, affluent market and efficient infrastructure in both Germany and Britain attract companies, but the high labor costs and strict labor laws there keep other companies away. The rapidly growing GDP in Brazil and India attracts companies, but violence and political unrest in Middle East countries deter investment. Perhaps the United States should lower its rate to reward companies that invest in jobs domestically. Lowering the U.S. corporate tax rate should also reduce unemployment and spur growth domestically.

2. Tax Inversions

An increasing number of U.S. companies are reincorporating in foreign countries to reduce their tax burden, and doing this typically by acquiring a foreign firm. For example, Illinois- based AbbVie recently acquired Dublin-based Shire PLC for $54 billion and Pennsylvania-based Mylan acquired Abbott Laboratories’ overseas generic drugs segment for $5.3 billion. Whenever a U.S. firm acquires a foreign firm and adopts that firm’s lower tax rate or establishes a holding company in a foreign country and adopts that firm’s lower tax rate, the transaction is called an inversion. Inversions are becoming common out of fear that politicians will soon eliminate that cross-border tax strategy. The U.S. Treasury Department installed some new rules in September 2014 to curtail inversions, but those rules had little effect. Under consideration currently are U.S.-based Pfizer and Medtronic bidding for Actavis (based in Ireland) and Covidien (based in Ireland), respectively, and Chiquita (based in Charlotte, NC) recently acquiring Fyffes (based in Ireland). Ireland in particular is taking steps to close the best-known corporate tax loophole.

Tax inversions have led to a higher dollar value of mergers and acquisitions in the United States in 2014-2015 than in the past 10 years. Inversions are common because the old alternative strategy of simply reincorporating in, say Bermuda or the Cayman Islands, has been virtually eliminated by politicians. Mylan, like many firms, used its foreign acquisition to reincorporate in the Netherlands, and then transfer pretax income from their domestic operations to their foreign parent through intercompany debt. Similarly, Salix Pharmaceuticals in North Carolina recently acquired an Italian drug company and reincorporated in Ireland in the process. Congress’s Joint Committee on Taxation says eliminating inversions would yield $19.46 billion more in tax revenue for the United States over 10 years, but this will likely not get done for several years.

Source: David Fred, David Forest (2016), Strategic Management: A Competitive Advantage Approach, Concepts and Cases, Pearson (16th Edition).

18 May 2021

17 May 2021

17 May 2021

17 May 2021

17 May 2021

17 May 2021