To be successful in world markets, U.S. managers must obtain a better knowledge of historical, cultural, and religious forces that motivate and drive people in other countries. For multinational firms, knowledge of business culture variation across countries can be essential for gaining and sustaining competitive advantage. An excellent website to visit on this topic is www.worldbusinessculture. com, where you may select any country in the world and check out how business culture varies in that country versus other lands. In Japan, for example, business relations operate within the context of Wa, which stresses group harmony and social cohesion. In China, business behavior revolves around guanxi, or personal relations. In South Korea, activities involve concern for inhwa, or harmony based on respect of hierarchical relationships, including obedience to authority.3

In Europe, it is generally true that the farther north on the continent, the more participatory the management style. Most European workers are unionized and enjoy more frequent vacations and holidays than U.S. workers. A 90-minute lunch break plus 20-minute morning and afternoon breaks are common in European firms. Many Europeans resent pay-for-performance, commission salaries, and objective measurement and reward systems. This is true especially of workers in southern Europe. Many Europeans also find the notion of team spirit difficult to grasp because the unionized environment has dichotomized worker-management relations throughout Europe.

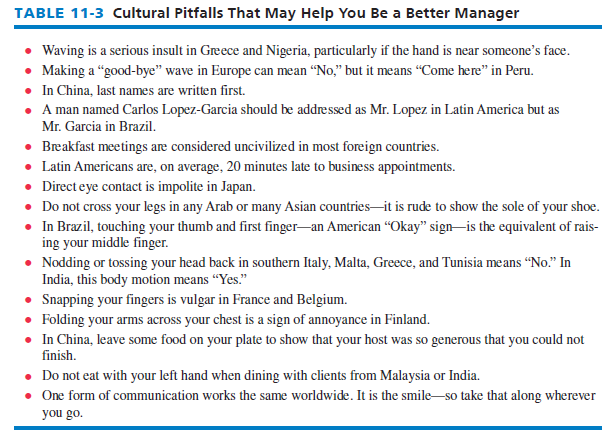

A weakness of some U.S. firms in competing with Pacific Rim firms is a lack of understanding of Asian cultures, including how Asians think and behave. Spoken Chinese, for example, has more in common with spoken English than with spoken Japanese or Korean. U.S. managers consistently put more weight on being friendly and liked, whereas Asian and European managers often exercise authority without this concern. Americans tend to use first names instantly in business dealings with foreigners, but foreigners find this presumptuous. In Japan, for example, first names are used only among family members and intimate friends; even longtime business associates and coworkers shy away from the use of first names. Table 11-3 lists other cultural differences or pitfalls that would benefit U.S. managers.

Managers from the United States place greater emphasis on short-term results than do foreign managers. In marketing, for example, Japanese managers strive to achieve “everlasting customers,” whereas many Americans strive to make a one-time sale. Marketing managers in Japan see making a sale as the beginning, not the end, of the selling process. This is an important distinction. Japanese managers often criticize U.S. managers for worrying more about shareholders, whom they do not know, than employees, whom they do know. Americans refer to “hourly employees,” whereas many Japanese companies still refer to “lifetime employees.”

Rose Knotts summarized some important cultural differences between U.S. and foreign managers.4 Awareness and consideration of these differences can enable a manager to be more effective, regardless of his or her own nationality.

- Americans place an exceptionally high priority on time, viewing time as an asset. Many foreigners place more worth on relationships. This difference results in foreign managers often viewing U.S. managers as “more interested in business than people.”

- Personal touching and distance norms differ around the world. Americans generally stand about three feet from each other when carrying on business conversations, but Arabs and Africans stand about one foot apart. Touching another person with the left hand in business dealings is taboo in some countries.

- Family roles and relationships vary in different countries. For example, males are valued more than females in some cultures, and peer pressure, work situations, and business interactions reinforce this phenomenon.

- Business and daily life in some societies are governed by religious factors. Prayer times, holidays, daily events, and dietary restrictions, for example, need to be respected by managers not familiar with these practices in some countries.

- Time spent with the family and the quality of relationships are more important in some cultures than the personal achievement and accomplishments espoused by the traditional U.S. manager.

- Many cultures around the world value modesty, team spirit, collectivity, and patience much more than competitiveness and individualism, which are so important in the United States.

- Punctuality is a valued personal trait when conducting business in the United States, but it is not revered in many of the world’s societies.

- Eating habits also differ dramatically across cultures. For example, belching is acceptable in some countries as evidence of satisfaction with the food that has been prepared. Chinese culture considers it good manners to sample a portion of each food served.

- To prevent social blunders when meeting with managers from other lands, one must learn and respect the rules of etiquette of others. Sitting on a toilet seat is viewed as unsanitary in most countries, but not in the United States. Leaving food or drink after dining is considered impolite in some countries, but not in China. Bowing instead of shaking hands is customary in many countries. Some cultures view Americans as unsanitary for locating toilet and bathing facilities in the same area, whereas Americans view people of some cultures as unsanitary for not taking a bath or shower every day.

- Americans often do business with individuals they do not know, unlike businesspersons in many other cultures. In Mexico and Japan, for example, an amicable relationship is often mandatory before conducting business.

In many countries, effective managers are those who are best at negotiating with government bureaucrats, rather than those who inspire workers. Many U.S. managers are uncomfortable with nepotism, which is practiced in some countries. The United States defends women from sexual harassment, defends minorities from discrimination, and allows gay marriage, but not all countries embrace the same values. American managers in China have to be careful about how they arrange office furniture because Chinese workers believe in feng shui, the practice of harnessing natural forces. Also, U.S. managers in Japan have to be careful about nemaswashio, whereby Japanese workers expect supervisors to alert them privately of changes rather than informing them in a meeting. Japanese managers have little appreciation for versatility, expecting all managers to be the same. In Japan, “If a nail sticks out, you hit it into the wall,” says Brad Lashbrook, an international consultant for Wilson Learning.

Probably the biggest obstacle to the effectiveness of U.S. managers—or managers from any country working in another—is the fact that it is almost impossible to change the attitude of a foreign workforce. “The system drives you; you cannot fight the system or culture,” says Bill Parker, president of Phillips Petroleum in Norway. For example, in the Middle East, gifts should not be made of pigskin, and should not be any type of alcohol, because Muslins do not eat pork or drink alcohol. In India, cows are revered, so no leather gifts.

Communication Differences across Countries

Communication may be the most important word in strategic management. Americans increasingly interact with managers in other countries, so it is important to understand communication differences across countries. Americans sometimes come across as intrusive, manipulative, and garrulous; this impression may reduce their effectiveness in communication. Asian managers view extended periods of silence as important for organizing and evaluating one’s thoughts, whereas U.S. managers have a low tolerance for silence. Sitting through a conference without talking is unproductive in the United States, but it is viewed as positive in Japan if one’s silence helps preserve unity. Managers from the United States are much more action-oriented than their counterparts around the world; they rush to appointments, conferences, and meetings-and then feel the day has been productive. But for many foreign managers, resting, listening, meditating, and thinking is considered productive.

Most Japanese managers are reserved, quiet, distant, introspective, and other oriented, whereas most U.S. managers are talkative, insensitive, impulsive, direct, and individual-oriented. Americans often perceive Japanese managers as wasting time and carrying on pointless conversations, whereas U.S. managers often use blunt criticism, ask prying questions, and make quick decisions. These kinds of communication differences have disrupted many potentially productive Japanese-American business endeavors. Viewing the Japanese communication style as a prototype for all Asian cultures is a stereotype that must be avoided.

Like many Asian and African cultures, the Japanese are nonconfrontational. They have a difficult time saying “no,” so you must be vigilant at observing their nonverbal communication. Rarely refuse a request, no matter how difficult or nonprofitable it may appear at the time. In communicating with Japanese, phrase questions so that they can answer yes—for example, “Do you disagree with this?” Group decision making and consensus are vitally important. The Japanese often remain silent in meetings for long periods of time and may even close their eyes when they want to listen intently.

Source: David Fred, David Forest (2016), Strategic Management: A Competitive Advantage Approach, Concepts and Cases, Pearson (16th Edition).

18 May 2021

17 May 2021

17 May 2021

17 May 2021

17 May 2021

17 May 2021