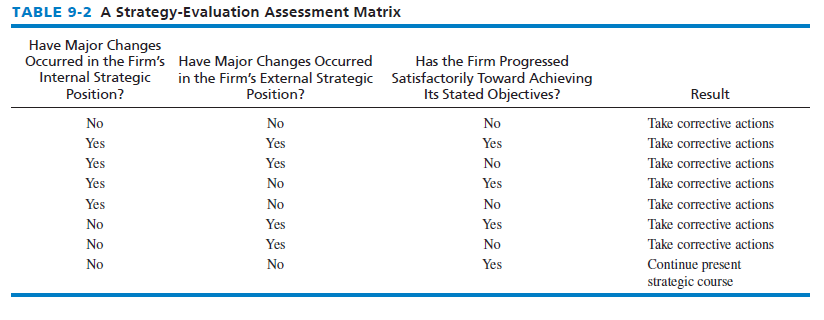

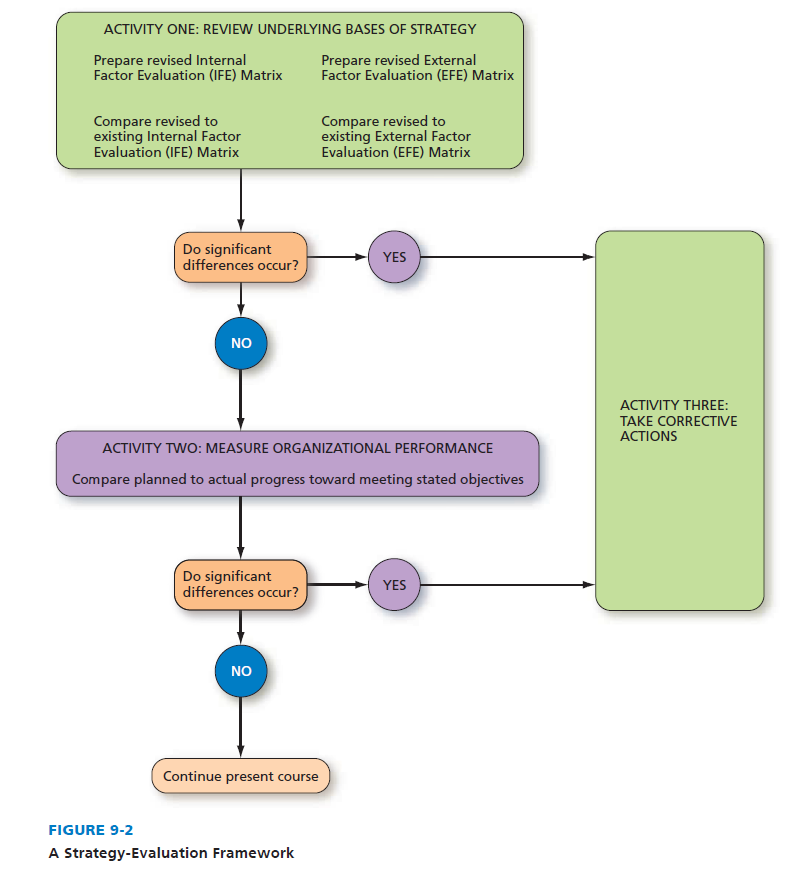

Table 9-2 summarizes the three strategy-evaluation activities in terms of key questions that should be addressed, alternative answers to those questions, and appropriate actions for an organization to take. Notice that corrective actions are almost always needed except when (1) external and internal factors have not significantly changed and (2) the firm is progressing satisfactorily toward achieving stated objectives. Relationships among strategy-evaluation activities are illustrated in Figure 9-2.

1. Reviewing Bases of Strategy

As shown in Figure 9-2, reviewing the underlying bases of an organization’s strategy could be approached by developing a revised EFE Matrix and IFE Matrix. A revised IFE Matrix should focus on changes in the organization’s management, marketing, finance and accounting, production and operations, research and development (R&D), and management information systems (MIS) strengths and weaknesses. A revised EFE Matrix should indicate how effective a firm’s strategies have been in response to key opportunities and threats. This analysis could also address such questions as the following:

- How have competitors reacted to our strategies?

- How have competitors’ strategies changed?

- Have major competitors’ strengths and weaknesses changed?

- Why are competitors making certain strategic changes?

- Why are some competitors’ strategies more successful than others?

- How satisfied are our competitors with their present market positions and profitability?

- How far can our major competitors be pushed before retaliating?

- How could we more effectively cooperate with our competitors?

Numerous external and internal factors can prevent firms from achieving long-term and annual objectives. Externally, actions by competitors, changes in demand, changes in technology, economic changes, demographic shifts, and governmental actions may prevent objectives from being accomplished. Internally, ineffective strategies may have been chosen or implementation activities may have been poor. objectives may have been too optimistic. Thus, failure to achieve objectives may not be the result of unsatisfactory work by managers and employees. All organizational members need to know this to encourage their support for strategy-evaluation activities. organizations desperately need to know as soon as possible when their strategies are not effective. Sometimes managers and employees on the front lines discover this well before strategists.

External opportunities and threats and internal strengths and weaknesses that represent the bases of current strategies should continually be monitored for change. It is not a question of whether these factors will change, but rather when they will change, and in what ways. Here are some key questions to address in evaluating strategies:

- Are our internal strengths still strengths?

- Have we added other internal strengths? if so, what are they?

- are our internal weaknesses still weaknesses?

- Do we now have other internal weaknesses? if so, what are they?

- are our external opportunities still opportunities?

- are there now other external opportunities? if so, what are they?

- are our external threats still threats?

- are there now other external threats? if so, what are they?

- are we vulnerable to a hostile takeover?

2. Measuring Organizational Performance

Another important strategy-evaluation activity is measuring organizational performance. This activity includes comparing expected results to actual results, investigating deviations from plans, evaluating individual performance, and examining progress being made toward meeting stated objectives. Both long-term and annual objectives are commonly used in this process. Criteria for evaluating strategies should be measurable and easily verifiable. Criteria that predict results may be more important than those that reveal what already has happened. For example, rather than simply being informed that sales in the last quarter were 20 percent under what was expected, strategists need to know that sales in the next quarter may be 20 percent below standard unless some action is taken to counter the trend. Really effective control requires accurate forecasting.

Failure to make satisfactory progress toward accomplishing long-term or annual objectives signals a need for corrective actions. Many factors, such as unreasonable policies, unexpected turns in the economy, unreliable suppliers or distributors, or ineffective strategies, can result in unsatisfactory progress toward meeting objectives. Problems can result from ineffectiveness (not doing the right things) or inefficiency (poorly doing the right things).

Determining which objectives are most important in the evaluation of strategies can be difficult. Strategy evaluation is based on both quantitative and qualitative criteria. Selecting the exact set of criteria for evaluating strategies depends on a particular organization’s size, industry, strategies, and management philosophy. an organization pursuing a retrenchment strategy, for example, could have a different set of evaluative criteria from an organization pursuing a market- development strategy. Quantitative criteria commonly used to evaluate strategies are financial ratios, often monitored for each segment of the firm. Strategists use financial ratios to make three critical comparisons:

- Compare the firm’s performance over different time periods.

- Compare the firm’s performance to competitors.

- Compare the firm’s performance to industry averages.

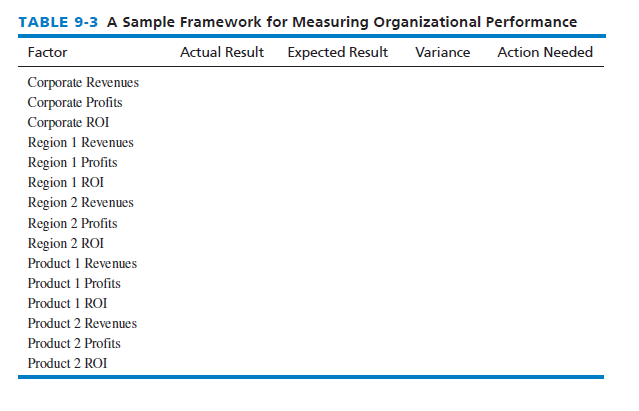

Many variables can and should be included in measuring organizational performance. As indicated in Table 9-3, typically a favorable or unfavorable variance is recorded monthly, quarterly, and annually, and resultant actions needed are then determined.

Some potential problems are associated with using only quantitative criteria for evaluating strategies. First, most quantitative criteria are geared to annual objectives rather than long-term objectives. also, different accounting methods can provide different results on many quantitative criteria. Third, intuitive judgments are almost always involved in deriving quantitative criteria. Thus, qualitative criteria are also important in evaluating strategies. Human factors such as high absenteeism and turnover rates, poor production quality and quantity rates, or low employee satisfaction can be underlying causes of declining performance. Marketing, finance and accounting, R&D, or MiS factors can also cause financial problems. The need for a “balanced” quantitative/ qualitative approach in evaluating strategies gives rise in a moment to discussion of the balanced scorecard.

Some additional key questions that reveal the need for qualitative judgments in strategy evaluation are as follows:

- How good is the firm’s balance of investments between high-risk and low-risk projects?

- How good is the firm’s balance of investments between long-term and short-term projects?

- How good is the firm’s balance of investments between slow-growing markets and fast-growing markets?

- How good is the firm’s balance of investments among different divisions?

- To what extent are the firm’s alternative strategies socially responsible?

- What are the relationships among the firm’s key internal and external strategic factors?

- How are major competitors likely to respond to particular strategies?

3. Taking Corrective Actions

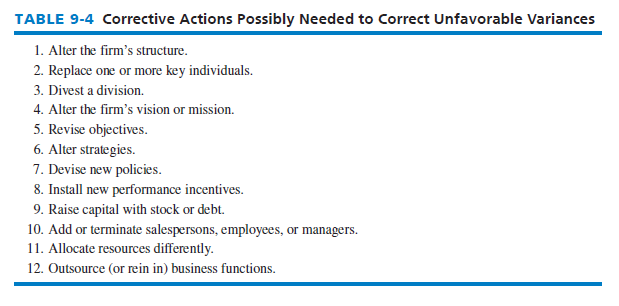

The final strategy-evaluation activity, taking corrective actions, requires making changes to competitively reposition a firm for the future. As indicated in Table 9-4, examples of changes that may be needed are altering an organization’s structure, replacing one or more key individuals, selling a division, or revising a business mission. Other changes could include establishing or revising objectives, devising new policies, issuing stock to raise capital, adding additional salespersons, differently allocating resources, or developing new performance incentives. Taking corrective actions does not necessarily mean that existing strategies will be abandoned or even that new strategies must be formulated.

The probabilities and possibilities for incorrect or inappropriate actions increase geometrically with an arithmetic increase in personnel. Any person directing an overall undertaking must check on the actions of the participants as well as the results they have achieved. If either the actions or results do not comply with preconceived or planned achievements, then corrective actions are needed.6

McDonald’s is currently taking extensive corrective actions after recently reporting steep declines in its revenues and profits. A company spokesman said, “We will diligently work to enhance our marketing, simplify our menu, and implement a more locally driven organizational structure to increase relevance with consumers.” In taking corrective actions, McDonald’s recently fired a CEO, hired another CEO, shuffled its management ranks, created a new organizational structure, and revamped its menu.

No organization can survive as an island; no organization can escape change. Taking corrective actions is necessary to keep an organization on track toward achieving stated objectives. In his thought-provoking books Future Shock and The Third Wave, Alvin Toffler argued that business environments are becoming so dynamic and complex that they threaten people and organizations with future shock, which occurs when the nature, types, and speed of changes overpower an individual’s or organization’s ability and capacity to adapt. Strategy evaluation enhances an organization’s ability to adapt successfully to changing circumstances.

Taking corrective actions raises employees’ and managers’ anxieties. Research suggests that participation in strategy-evaluation activities is one of the best ways to overcome individuals’ resistance to change. According to Erez and Kanfer, individuals accept change best when they have a cognitive understanding of the changes, a sense of control over the situation, and an awareness that necessary actions are going to be taken to implement the changes.7

Strategy evaluation can lead to strategy-formulation and/or strategy-implementation changes, or no changes at all. Strategists cannot escape having to revise strategies and implementation approaches sooner or later. Hussey and Langham offered the following insight on taking corrective actions:

Resistance to change is often emotionally based and not easily overcome by rational argument. Resistance may be based on such feelings as loss of status, implied criticism of present competence, fear of failure in the new situation, annoyance at not being consulted, lack of understanding of the need for change, or insecurity in changing from well-known and fixed methods. It is necessary, therefore, to overcome such resistance by creating situations of participation and full explanation when changes are envisaged.8

Corrective actions should place an organization in a better position to capitalize on internal strengths; to take advantage of key external opportunities; to avoid, reduce, or mitigate external threats; and to improve internal weaknesses. Corrective actions should have a proper time horizon and an appropriate amount of risk. They should be internally consistent and socially responsible. Perhaps most important, corrective actions strengthen an organization’s competitive position in its basic industry. Continuous strategy evaluation keeps strategists close to the pulse of an organization and provides information needed for an effective strategic-management system. Carter Bayles described the benefits of strategy evaluation as follows:

Evaluation activities may renew confidence in the current business strategy or point to the need for actions to correct some weaknesses, such as erosion of product superiority or technological edge. In many cases, the benefits of strategy evaluation are much more far-reaching, for the outcome of the process may be a fundamentally new strategy that will lead, even in a business that is already turning a respectable profit, to substantially increased earnings.

Source: David Fred, David Forest (2016), Strategic Management: A Competitive Advantage Approach, Concepts and Cases, Pearson (16th Edition).

I am not real superb with English but I get hold this really easygoing to interpret.