1. Turbulent Times and the Changing Workplace

Today’s organizations face an almost continual need for change. Sometimes, forces outside the organization bring about changes, such as when a powerful retailer such as Wal-Mart demands annual price cuts, or when a key supplier goes out of business. Many U.S. companies revised their procedures to comply with provisions of the Sarbanes-Oxley corporate governance reform law. In China, organizations feel pressure from the government to increase wages to help work- ers cope with rising food costs. At the same time, costs of steel and other raw materials are sky- rocketing for Chinese companies seeking to expand their businesses.2 These

outside forces compel managers to look for greater efficiencies in operations and other changes to keep their organizations profitable. Other times, manag- ers within the company want to initiate major changes, such as forming employee-participation teams, introducing new products, or instituting new training systems, but they don’t know how to make the change successful. Organizations must embrace many types of change. Businesses must develop improved production technologies, create new products and services desired in the marketplace, implement new administrative systems, and upgrade employees’ skills. Companies such as Samsung, Apple, Toyota, and General Electric implement all of these changes and more.

How important is organizational change? Consider this: The parents of today’s college students grew up without e-mail, digital cameras, video on demand, laptop computers, iPods, laser checkout systems, and online shopping. As companies that produce the new products and services pros- per, many companies are caught with outdated products and failed tech- nologies. Today’s successful companies are constantly innovating. For example, Johnson & Johnson Pharmaceuticals uses biosimulation software from Entelos that compiles all known information about a disease such as diabetes or asthma and runs extensive virtual tests of new drug candidates.

With a new-drug failure rate of 50 percent even at the last stage of clinical trials, the process helps scientists cut the time and expense of early testing and focus their efforts on the most promising prospects. Telephone com- panies such as AT&T are investing in technology to push deeper into the television and broadband markets. Automakers Chrysler, General Motors, and Toyota are perfecting fuel-cell power systems that could make today’s internal combustion engine as obsolete as the steam locomotive.3 Computer companies are developing computers that are smart enough to configure themselves, balance huge workloads, and know how to anticipate and fix problems before they happen.4 Organizations that change successfully are both profitable and admired.

Organizational change is defined as the adoption of a new idea or behavior by an organization.5 In this chapter, we look at how organizations can be designed to respond to the environment through internal change and development. First we look at two key aspects of change in organizations: introducing new products and technologies and changing people and culture. Then we examine the basic forces for change and present a model for planned organizational change. Finally, we discuss how managers implement change, including overcoming resistance.

2. Changing Things: New Products and Technologies

Competition is more intense than ever before, and companies are driven by a new innova- tion imperative. The past decade’s attention to efficiency in operations is no longer enough to keep organizations successful in a new, hypercompetitive environment. To thrive, com- panies must innovate more—and more quickly—than ever. One vital area for innovation is introducing new products and technologies.

A product change is a change in the organization’s product or service outputs. Prod-uct and service innovation is the primary way in which organizations adapt to changes in markets, technology, and competition.6 Examples of new products include Apple’s iPhone and the iPod Hi-Fi, Glad Force Flex trash bags, the Motorola RAzr 2 V8 cell phone, and The Smart ForTwo car. The introduction of e-file, which allows online filing of tax returns, by the U.S. Internal Revenue Service (IRS) is an example of a new service innovation. Product changes are related to changes in the technology of the organization. Not all prod- uct changes are good ideas, as show in the Business Blooper box.

A technology change is a change in the organization’s production process—how the organization does its work. Technology changes are designed to make the production of a product or service more efficient. The adoption of automatic mail sorting machines by the U.S. Postal Service is one example of a technology change.

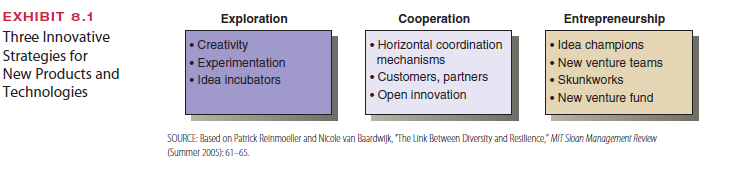

Three critical innovation strategies for changing products and technologies are illus-

trated in Exhibit 8.1.7 The first strategy, exploration, involves designing the organization to encourage creativity and the initiation of new ideas. The strategy of cooperation refers to cre- ating conditions and systems to facilitate internal and external coordination and knowledge sharing. Finally, entrepreneurship means that managers put in place processes and structures to ensure that new ideas are carried forward for acceptance and implementation.

2.1. EXPLORATION

Exploration is the stage where ideas for new products and technologies are born. Managers design the organization for exploration by establishing conditions that encourage creativity and allow new ideas to spring forth. Creativity, which refers to the generation of novel ideas that might meet perceived needs or respond to opportunities for the organization, is the essential first step in innovation.8 People noted for their creativity include Edwin Land, who invented the Polaroid camera; Richard Tait and Whit Alexander, who came up with the idea for the mega-hit board game Cranium; and Swiss engineer George de Mestral, who created Velcro after noticing the tiny hooks on the burrs caught on his wool socks. Each of these people saw unique and creative opportunities in a familiar situation.

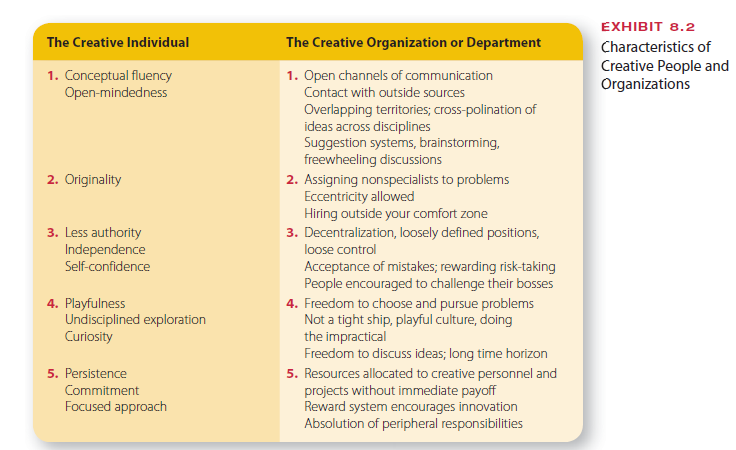

Characteristics of highly creative people are illustrated in the left-hand column of Exhibit 8.2. Creative people often are known for originality, open-mindedness, curiosity, a focused approach to problem solving, persistence, a relaxed and playful attitude, and receptivity to new ideas.9 Creativity can also be designed into organizations. Companies or departments within companies can be organized to be creative and initiate ideas for change. Most compa- nies want more highly creative employees and often seek to hire creative individuals. However, the individual is only part of the story, and each of us has some potential for creativity. Manag- ers are responsible for creating a work environment that allows creativity to flourish.10

The characteristics of creative organizations correspond to those of individuals, as illus- trated in the right-hand column of Exhibit 8.2. Creative organizations are loosely struc- tured. People find themselves in a situation of ambiguity, assignments are vague, territories overlap, tasks are poorly defined, and much work is done through teams. Managers strive to involve employees in a varied range of projects, so that people are not stuck in the rhythm of routine jobs, and they drive out the fear of making mistakes that can inhibit cre-ative thinking.11 Creative organizations have an internal culture of playfulness, freedom, challenge, and grassroots participation.12 They harness all potential sources of new ideas.

Advertising agency Leo Burnett holds a regular “Inspire Me” day, when one team takes the rest of the department out to do something totally unrelated to advertising. One team took the group to a Mexican wrestling match, where team members showed up in cos- tumes and masks like some of the more ardent wrestling fans. One idea that grew out of the experience was a new slogan for The Score, a sports network: “The Score: Home for the Hardcore.”13 To keep creativity alive at Google, managers let people spend 20 percent of their time working on any project they choose, even if the project doesn’t tie in with the company’s central mission. Many Google managers hold open office hours two or three times a week, when anyone can come by to bat around ideas.14

The most creative companies embrace risk and encourage employees to experiment and make mistakes. At software company Intuit, managers in the various divisions hold free- association sessions at least once a week, where people can propose all sorts of seemingly kooky ideas without embarrassment or fear.15 One manager at Intel used to throw a dinner party every month for the “failure of the month,” demonstrating to people that failure was an inevitable and accepted part of risk-taking.16 Jim Read, president of the Read Corpora- tion, says, “When my employees make mistakes trying to improve something, I give them a round of applause. No mistakes mean no new products. If they ever become afraid to make one, my company is doomed.”17

Another popular way to encourage new ideas within the organization is the idea incubator. An idea incubator provides a safe harbor where ideas from employees through- out the company can be developed without interference from company bureaucracy or poli- tics.18 The great value of an internal idea incubator is that an employee with a good idea has a specific place to go to develop it, rather than having to shop the idea all over the company and hope someone pays attention. Companies as diverse as Boeing, Adobe Systems, Ball Aerospace, UPS, and Ziff Davis are using incubators to quickly produce products and services related to the company’s core business.19

2.2. COOPERATION

Another important aspect of innovation is providing mechanisms for both internal and ex- ternal coordination. Ideas for product and technology innovations typically originate at lower levels of the organization and need to flow horizontally across departments. Imple- mentation of an innovation typically requires changes in behavior across several depart- ments. In addition, people and organizations outside the firm can be rich sources of inno- vative ideas. Lack of innovation is widely recognized as one of the biggest problems facing today’s businesses. Consider that 72 percent of top executives surveyed by BusinessWeek and the Boston Consulting Group reported that innovation is a top priority, yet almost half said they are dissatisfied with their results in that area.20 Thus, many companies are under- going a transformation in the way they find and use new ideas, focusing on improving both internal and external coordination.

2.3. INTERNAL COORDINATION

Successful innovation requires expertise from several departments simultaneously, and failed innovation is often the result of failed cooperation.21 Companies that successfully innovate usually have the following characteristics:

- People in marketing have a good understanding of customer needs.

- Technical specialists are aware of recent technological developments and make effective use of new technology.

- Members from key departments—research, manufacturing, marketing—cooperate in the development of the new product.22

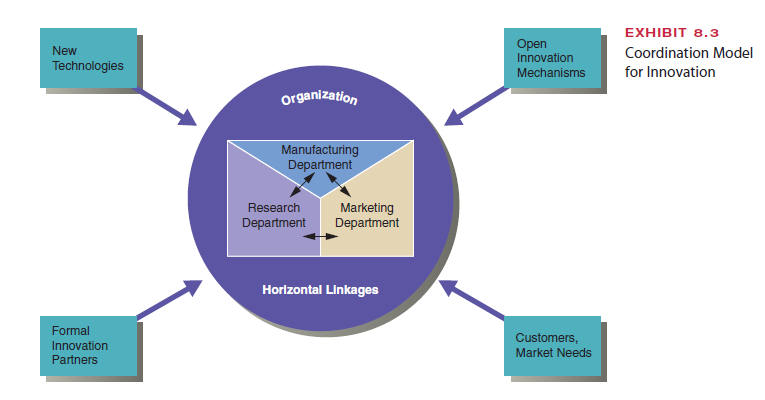

One approach to successful innovation is called the horizontal linkage model, which is illustrated in the center circle of Exhibit 8.3.23 The model shows that the research, manu- facturing, and sales and marketing departments within an organization must simultane- ously contribute to new products and technologies. People from these departments meet frequently in teams and task forces to share ideas and solve problems. For example, re- search people inform marketing of new technical developments to learn whether they will be useful to customers. Marketing people pass customer complaints to research to use in the design of new products and to manufacturing people to develop new ideas for improv- ing production speed and quality. Manufacturing informs other departments concerning whether a product idea can be manufactured within cost limits.

The appliance-maker Electrolux was struggling with spiraling costs and shrinking mar- ket share until CEO Hans Straberg introduced a new approach to product development that has designers, engineers, marketers, and production people working side-by-side to come up with hot new products such as the Pronto cordless stick vacuum, which gained a

50 percent market share in Europe within two years. “We never used to create new prod- ucts together,” says engineer Giuseppe Frucco. “The designers would come up with some- thing and then tell us to build it.” The new horizontal approach saves both time and money at Electrolux by avoiding the technical glitches that crop up as a new design moves through the development process.24

The horizontal linkage model is increasingly important in today’s high-pressure busi- ness environment that requires developing and commercializing products and services incredibly fast. Sprinting to market with a new product requires a parallel approach, or simultaneous linkage, among departments. This kind of teamwork is similar to a rugby match wherein players run together, passing the ball back

and forth as they move downfield.25 Speed is emerging as a pivotal strategic weapon in the global marketplace for a wide variety of industries.26 Stockholm’s H&M (Hennes & Mauritz) has become one of the hottest fashion retailers around because it can spot trends and rush items into stores in as little as 3 weeks. Nissan cut the time it takes to get a new car to market from 21 months to about 10.27 Some companies use fast-cycle teams to deliver products and services faster than competitors, giving them a significant strategic advantage. A fast-cycle team is a multifunc- tional, and sometimes multinational, team that works under stringent timelines and is provided with high levels of resources and empowerment to accomplish an acceler- ated product development project.28

2.4. EXTERNAL COORDINATION

Exhibit 8.3 also illustrates that organizations look outside their boundaries to find and develop new ideas. Engineers and researchers stay aware of new technological develop- ments. Marketing personnel pay attention to shifting market conditions and customer needs. Some organizations build formal strategic partnerships such as alliances and joint ven- tures to improve innovation success. Outsourcing partner- ships can help companies get things done incredibly fast.

Some leading cell phone makers, for example, work with outsourcing partner Cellon Inc. to take a new phone model from design to market in five months. Cellon, with operations in China, keeps a half-dozen basic designs that it can quickly customize for a particular client. Then, the company works with local manufacturers to rapidly move designs into production. People want hot new phones, and the life cycle of a cell phone model is about 9 months. Companies can’t afford the 12 to 18 months it typically takes to develop a new model from scratch.29

Today’s most successful companies are including customers, strategic partners, suppli- ers, and other outsiders directly in the product and service development process. One of the hottest trends is open innovation.30 Think of Google, which opened its mapping technology to the public, allowing programmers to combine Google’s maps with anything from real estate listings to local poker game sites.31 At online game designer Linden Lab’s Second Life, players have the freedom to create just about everything, from new characters to buildings to whole new games.32

In the past, most businesses generated their own ideas in house and then developed, manufactured, marketed, and distributed them, a closed innovation approach. Today, though, forward-looking companies are trying a different method. Open innovation means extending the search for and commercializing new ideas beyond the boundaries of the organization and even beyond the boundaries of the industry. Smart companies find and use ideas from anywhere within and outside the organization.33 Procter & Gamble, not so long ago a stodgy consumer products company, has become one of the country’s hottest innovators and a role model for the open innovation process.

Connecting with customers is also a critical aspect of open innovation. At companies such as P&G and Electrolux, rather than relying on focus groups, researchers now spend time with people in their homes, watching how they wash their dishes or clean their floors, and asking questions about their habits and frustrations with household chores. P&G’s CEO makes 10 to 15 visits a year to watch women applying their beauty products or doing their laundry.34

In line with the new way of thinking we discussed in Chapter 1, which sees partnership and collaboration as more important than independence and competition, the boundaries between an organization and its environment are becoming porous, so that ideas flow back and forth among different people and companies that engage in partnerships, joint ven-tures, licensing agreements, and other alliances. Japanese high-tech firms, such as Fujitsu, for example, are achieving rapid innovation by building strategic innovation communities that link managers from all levels with partners, customers, and other outsiders for devel- oping new products. Similarly, in the United States, external collaboration and innovation networking were key to IBM’s reemergence as a technology powerhouse.36

2.5. ENTREPRENEURSHIP

The third aspect of product and technology innovation is creating mechanisms to make sure new ideas are carried forward, accepted, and implemented. Here is where idea champions come in. The formal definition of an idea champion is a person who sees the need for and champions productive change within the organization. Wendy Black of Best Western Interna- tional championed the idea of coordinating the corporate mailings to the company’s 2,800 hoteliers into a single packet every two weeks. Some hotels were receiving three special mailings a day from different departments. Her idea saved $600,000 a year in postage alone.37

Remember: Change does not occur by itself. Personal energy and effort are required to successfully promote a new idea. Often a new idea is rejected by management. Champions are passionately committed to a new product or idea despite rejection by others. Robert Vincent was fired twice by two different division managers at a semiconductor company. Both times, he convinced the president and chairman of the board to reinstate him to con- tinue working on his idea for an airbag sensor that measures acceleration and deceleration. He couldn’t get approval for research funding, so Vincent pushed to complete another project in half the time and used the savings to support the new product development.38 At Kyocera Wireless, lead engineer Gary Koerper was a champion for the Smartphone. When he couldn’t get his company’s testing department to validate the new product, he had an outside firm do the testing for him—at a cost of about $30,000—without approval from Kyocera management. After the Smartphone was approved and went into production, de- mand was so great the company could barely keep up.39

Championing an idea successfully requires roles in organizations, as illustrated in Exhibit 8.4. Sometimes a single person may play two or more of these roles, but successful innovation in most companies involves an interplay of different people, each adopting one role. The inventor comes up with a new idea and understands its technical value but has neither the ability nor the interest to promote it for acceptance within the organization. The champion believes in the idea, confronts the organizational realities of costs and benefits, and gains the political and fi- nancial support needed to bring it to reality. The sponsor is a high-level manager who approves the idea, protects the idea, and removes major organizational barriers to acceptance. The critic counterbalances the zeal of the champion by challenging the concept and providing a reality test against hard-nosed criteria. The critic prevents people in the other roles from adopting a bad idea.40 Reed Hastings was inventor, champion, and critic all in one, as is often the case in small-business startups, as described in the Benchmarking box.

Managers can directly influence whether champions will flourish. When Texas Instru- ments studied 50 of its new-product introductions, a surprising fact emerged: Without ex- ception, every new product that failed lacked a zealous champion. In contrast, most of the new products that succeeded had a champion. Managers made an immediate decision: No new product would be approved unless someone championed it. Research confirms that successful new ideas are generally those that are backed by someone who believes in the idea wholeheartedly and is determined to convince others of its value.41

Another way to facilitate entrepreneurship is through a new-venture team. A new-venture team is a unit separate from the rest of the organization that is responsible for developing and initiating a major innovation.42 Motorola’s successful Razr cell phone was developed in an innovation lab 50 miles from employees’ regular offices in the company’s traditional research and development facility. Team members were free from the distrac- tions of their everyday routines and were given the autonomy to implement product ideas without the usual process of running things past regional managers.43 Whenever BMW Group begins developing a new car, the project’s team members—from engineering, design, production, marketing, purchasing, and finance—are relocated to a separate Research and Innovation Center, where they work collaboratively to speed the new prod- uct to market.44 New-venture teams give free rein to members’ creativity because their sep- arate facilities and location unleash people from the restrictions imposed by organizational rules and procedures. These teams typically are small, loosely structured, and flexible, reflecting the characteristics of creative organizations described in Exhibit 8.2.

One variation of a new-venture team is called a skunkworks.45 A skunkworks is a sep-arate small, informal, highly autonomous, and often secretive group that focuses on break- through ideas for the business. The original skunkworks, which still exists, was created by Lockheed Martin more than 50 years ago. The essence of a skunkworks is that highly talented people are given the time and freedom to let creativity reign.46 The laser printer was invented by a Xerox researcher who was transferred to a skunkworks, the Xerox Palo Alto Research Center (PARC), after his ideas about using lasers were stifled within the company for being “too impractical and expensive.”47 IBM is launching entirely new businesses by using the skunkworks concept. Managers identify emerging business opportunities (EBOs) that have the potential to become profitable businesses in the next five to seven years, and then put a senior leader in charge of building the business, often with only a few hand-picked colleagues. A digital media EBO, which helps companies manage video, audio, and still images, has grown into a $1.7 billion business in only three years.48

A related idea is the new-venture fund, which provides resources from which indi-viduals and groups can draw to develop new ideas, products, or businesses. At 3M, scien- tists can apply for Genesis Grants to work on innovative project ideas. 3M awards from 12 to 20 of these grants each year, ranging from $50,000 to $100,000 each, for researchers to hire supplemental staff, acquire equipment, or whatever is needed to develop the new idea. Intel has been highly successful with Intel Capital, which provides new-venture funds to both employees and outside organizations to develop promising ideas. An Intel employee came up with the idea for liquid crystal on silicon, a technology that lowers the cost of big- screen TV projection. “We took an individual who had an idea, gave him money to pursue it, and turned it into a business,” said Intel CEO Craig Barrett.49

Source: Daft Richard L., Marcic Dorothy (2009), Understanding Management, South-Western College Pub; 8th edition.

Well I sincerely liked studying it. This tip offered by you is very helpful for good planning.