1. SELECTION METHODS

In Chapter 7 on recruitment we considered the shortlisting process and the sifting of applications. We go on to look at selection methods in more detail, many of which may be used at different stages in the selection process, including shortlisting and sifting. We deal with interviews in depth in the interactive skills section at the end of Part 2 of the book.

1.1. Application forms

For a long time the application form was not suitable for use as a selection tool as it was a personal details form, which was intended to form the nucleus of the personnel record for the individual when they began work. As reservations grew about the validity of interviews for employment purposes, the more productive use of the application form was one of the avenues explored for improving the quality of decisions.

Forms were considered to act as a useful preliminary to employment interviews and decisions, either to present more information that was relevant to such deliberations, or to arrange such information in a standard way. This made sorting of applications and shortlisting easier and enabled interviewers to use the form as the basis for the interview itself, with each piece of information on the form being taken and developed in the interview. While there is heavy use of CVs for managerial and professional posts, many organisations, especially in the public sector, require both – off-putting to the applicant but helpful to the organisation in eliciting comparable data from all applicants.

The application form has been extended by some organisations to take a more significant part in the employment process. One form of extension is to ask for very much more, and more detailed, information from the candidate.

Another extension of application form usage has been in weighting, or biodata. Biodata have been defined by Anderson and Shackleton (1990) as ‘historical and verifiable pieces of information about an individual in a selection context usually reported on application forms’. Biodata are perhaps of most use for large organisations filling fairly large numbers of posts for which they receive extremely high numbers of applications. This method is an attempt to relate the characteristics of applicants to characteristics of a large sample of successful job holders. The obvious drawbacks of this procedure are, first, the time that is involved and the size of sample needed, so that it is only feasible where there are many job holders in a particular type of position. Second, it smacks of witchcraft to the applicants who might find it difficult to believe that success in a position correlates with being, inter alia, the first born in one’s family. Such methods are not currently well used and Taylor (2005) notes their controversial nature and perceived unfairness. In addition the 1998 Data Protection Act prohibits the use of an automated selection process (which biodata invariably are) as the only process used at any stage in the procedure.

Generally, application forms are used as a straightforward way of giving a standardised synopsis of the applicant’s history. This helps applicants present their case by providing them with a predetermined structure, it speeds the sorting and shortlisting or sifting of applications either by hand or elecronically and it guides the interviewers as well as providing the starting point for personnel records. There remain concerns about the reliability of applications forms and CVs and this issue is dealt with in Case study 8.2 at www.pearsoned.co.uk/torrington. Application forms are increasingly available electronically; this not only speeds up the process but also enables ‘key word’ searches of the data on the forms (for alternative ways in which this may be carried out see Mohamed et al. (2001)), but there are questions about the legality of this method when used alone. Initial sifting of electronic applications often includes a variety of methods including material from an application form as shown in the Woolworths examples in the Window on Practice.

1.2. Self-assessment and peer assessment

There is increasing interest in providing more information to applicants concerning the job. This may involve a video, an informal discussion with job holders or further information sent with the application form. This is often termed giving the prospective candidate a ‘realistic job preview’ (Wanous 1992), enabling them to assess their own suitability to a much greater extent and some organisations have taken the opportunity to provide a self-selection questionnaire on the company website. Another way of achieving this is by asking the candidates to do some form of pre-work. This may also involve asking them questions regarding their previous work experiences which would relate to the job for which they are applying.

1.3. Telephone interviewing

Telephone interviews can be used if speed is particularly important, and if geographical distance is an issue, as interviews with appropriate candidates can be arranged immediately. CIPD (2006) report that 56 per cent of organisations use this method of selection, a figure which has doubled since 2003, and probably reflects their use as one of a combination of screening tools, as well as a test of telephone manner, where required. Murphy (2005) reports similar figures and growth from an IRS survey. There is evidence that telephone interviews are best used as a part of a structured selection procedure, rather than alone – generally in terms of pre-selection for a face-to-face interview. However, they may also have an important role when selecting for jobs in which telephone manner is critical such as call centre and contact centre staff. There may be problems such as lack of non-verbal information, and difficulties getting hold of the applicant. However, positive aspects have been reported, such as concentration on content rather than the person. From an applicant perspective telephone interviews can be daunting, if they have no experience of them, and Murphy (2005) refers to and replicates checklists for organizations and candidates in the most effective use of such interviews.

1.4. Testing

The use of tests in employment procedures is surrounded by strong feelings for and against. Those in favour of testing in general point to the unreliability of the interview as a predictor of performance and the greater potential accuracy and objectivity of test data. Tests can be seen as giving credibility to selection decisions. Those against them either dislike the objectivity that testing implies or have difficulty in incorporating test evidence into the rest of the evidence that is collected. Questions have been raised as to the relevance of the tests to the job applied for and the possibility of unfair discrimination and bias. Also, some candidates feel that they can improve their prospects by a good interview performance and that the degree to which they are in control of their own destiny is being reduced by a dispassionate routine.

Tests remain heavily used, and the key issue debated currently is the extent to which tests should be administered over the web. CIPD (2006) with a larger sample found 75 per cent of organisations using general ability tests, 72 per cent of organisations using literacy/ numeracy tests and 60 per cent using personality tests, all of which had increased from previous years, and Murphy (2006) in an IRS survey found similar results. Testing is more likely to be used for management, professional and graduate jobs – although as testing on the web becomes more common it is likely to be used for a wider range of jobs.

Tests are chosen on the basis that test scores relate to, or correlate with, subsequent job performance, so that a high test score would predict high job performance and a low test score would predict low job performance.

1.5. Critical features of test use

Validity

Different types of validity can be applied to psychological tests. Personnel managers are most concerned with predictive validity, which is the extent to which the test can predict subsequent job performance. Predictive validity is measured by relating the test scores to measures of future performance, such as error rate, production rate, appraisal scores, absence rate or whatever criteria are important to the organisation. Sometimes performance is defined as the level of the organisation to which the individual has been promoted – so the criteria here are organisational rather than job specific. If test scores relate highly to future performance, however defined, then the test is a good predictor.

Reliability

The reliability of a test is the degree to which the test measures consistently whatever it does measure. If a test is highly reliable, then it is possible to put greater weight on the scores that individuals receive on the test. However, a highly reliable test is of no value in the employment situation unless it also has high validity.

Use and interpretation

Tests need to be used and interpreted by trained or qualified testers. Test results, especially personality tests, require very careful interpretation as some aspects of personality will be measured that are irrelevant to the job. The British Psychological Society (BPS) can provide a certificate of competence for occupational testing at levels A and B. Both the BPS and CIPD have produced codes of practice for occupational test use. It is recommended that tests are not used in a judgemental, final way, but to stimulate discussion with the candidate based on the test results and that feedback is given to candidates. The International Test Commission also provide guidelines on computer-based and Internet-delivered testing and their website is included at the end of this Part of the book. In addition it is recommended in the CIPD code that test data alone should not be used to make a selection decision (which could contravene the 1998 Data Protection Act), but should always be used as part of a wider process where inferences from test results can be backed up by other sources. Norm tables and the edition date of a test are also important features to check. For example Ceci and Williams (2000) warn that intelligence is a relative concept and that the norm tables change over time – so using an old test with old norm tables may be misleading.

1.6. Problems with using tests

A number of problems can be incurred when using tests.

- In the last section we commented that a test score that was highly related to performance criteria has good validity. The relationship between test scores and performance criteria is usually expressed as a correlation coefficient (r). If r = 1 then test scores and performance would be perfectly related; if r = 0 there is no relationship whatsoever. A correlation coefficient of r =4 is comparatively good in the testing world and this level of relationship between test scores and performance is generally seen as acceptable. Tests are, therefore, not outstanding predictors of future performance.

- Validation procedures are very time consuming, but are essential to the effective use of tests. There are concerns that with the growth of web testing, new types of tests, such as emotional intelligence tests, are being developed without sufficient validation (Tulip 2002).

- The criteria that are used to define good job performance in developing the test are often inadequate. They are subjective and may account to some extent for the mediocre correlations between test results and job performance.

- Tests are often job specific. If the job for which the test is used changes, then the test can no longer be assumed to relate to job performance in the same way. Also, personality tests only measure how individuals see themselves at a certain time and cannot therefore be reliably reused at a later time.

- Tests may not be fair as there may be a social, sexual or racial bias in the questions and scoring system. People from some cultures may, for example, be unused to ‘working against the clock’.

- Increasingly organisations are using competencies as a tool to identify and develop the characteristics of high performance. However, as Fletcher (1996) has pointed out, it is difficult to relate these readily to psychological tests. Rogers (1999) reports research which suggests the two approaches are compatible – but there is little evidence to support this so far.

1.7. Types of test for occupational use

Aptitude tests

People differ in their performance of tasks, and tests of aptitude (or ability) measure an individual’s potential to develop in either specific or general terms. This is in contrast to attainment tests, which measure the skills an individual has already acquired. When considering the results from aptitude tests it is important to remember that a simple relationship does not exist between a high level of aptitude and a high level of job performance, as other factors, such as motivation, also contribute to job performance.

Aptitude tests can be grouped into two categories: those measuring general mental ability or general intelligence, and those measuring specific abilities or aptitudes.

General intelligence tests

Intelligence tests, sometimes called mental ability tests, are designed to give an indication of overall mental capacity. A variety of questions are included in such tests, including vocabulary, analogies, similarities, opposites, arithmetic, number extension and general information. Ability to score highly on such tests correlates with the capacity to retain new knowledge, to pass examinations and to succeed at work. However, the intelligence test used would still need to be carefully validated in terms of the job for which the candidate was applying. And Ceci and Williams (2000) note that intelligence is to some extent determined by the context – so an individual’s test score may not reflect capacity to act intelligently. Indeed practical intelligence, associated with success in organisations, may be different from the nature of intelligence as measured by tests (Williams and Sternberg 2001). Examples of general intelligence tests are found in IDS (2004).

Special aptitude tests

There are special tests that measure specific abilities or aptitudes, such as spatial abilities, perceptual abilities, verbal ability, numerical ability, motor ability (manual dexterity) and so on. An example of a special abilities test is the Critical Reasoning Test developed by Smith and Whetton (see IDS 2004).

Trainability tests

Trainability tests are used to measure a potential employee’s ability to be trained, usually for craft-type work. The test consists of the applicants doing a practical task that they have not done before, after having been shown or ‘trained’ how to do it. The test measures how well they respond to the ‘training’ and how their performance on the task improves. Because it is performance at a task that is being measured, these tests are sometimes confused with attainment tests; however, they are more concerned with potential ability to do the task and response to training.

Attainment tests

Whereas aptitude tests measure an individual’s potential, attainment or achievement tests measure skills that have already been acquired. There is much less resistance to such tests of skills. Few candidates for a secretarial/administrative post would refuse to take a keyboard speed test, or a test on ‘Word’, ‘PowerPoint’ or ‘Excel’ software before interview. The candidates are sufficiently confident of their skills to welcome the opportunity to display them and be approved. Furthermore, they know what they are doing and will

know whether they have done well or badly. They are in control, whereas they feel that the tester is in control of intelligence and personality tests as the candidates do not understand the evaluation rationale. Attainment tests are often devised by the employer.

Personality tests

The debate still rages as to the importance of personality for success in some jobs and organisations. The need for personality assessment may be high but there is even more resistance to tests of personality than to tests of aptitude, partly because of the reluctance to see personality as in any way measurable. There is much evidence to suggest that personality is also context dependent, and Iles and Salaman (1995) also argue that personality changes over time. Both of these factors further complicate the issue. Personality tests are mainly used for management, professional and graduate jobs, although there is evidence of their use when high-performance teams are developed.

Theories of human personality vary as much as theories of human intelligence. Jung, Eysenck and Cattell, among others, have all proposed different sets of factors/traits which can be assessed to describe personality. Based on research to date Robertson (2001) argues that it is now possible to state that there are five basic building blocks of personality: extro- version/introversion; emotional stability; agreeableness; conscientiousness and openness to new experiences. Myers-Briggs is a well used personality test; for details see McHenry (2002).

It is dangerous to assume that there is a standard profile of ‘the ideal employee’ (although this may fit nicely with theories of culture change) or the ideal personality for a particular job, as the same objectives may be satisfactorily achieved in different ways by different people. Another problem with the use of personality tests is that they rely on an individual’s willingness to be honest, as the socially acceptable answer or the one best in terms of the job are seemingly easy to pick out, although ‘lie detector’ questions are usually built in. Ipsative tests (as opposed to normative tests)[1] seek to avoid the social desirability problem by using a different test structure – but other problems arise from this approach. Heggestad et al. (2006) suggest that in their pure form ipsative tests are inappropriate for selection and that in their partial form they might be just as susceptible to faking as normative tests.

Dalen et al. (2001) did show that tests are manipulable but not sufficiently for the candidate to match an ideal profile, and that such manipulation would be exposed by detection measures within the test. There is a further problem that some traits measured by the test will not be relevant in terms of performance on the job. There is at the time of writing an interest in emotional intelligence – tests measure self-awareness, self-motivation, emotional control, empathy and the ability to understand and inspire others.

1.8. Group selection methods and assessment centres

Group methods

The use of group tasks to select candidates is not new – the method dates back to the Second World War – but such measures have gained greater attention through their use in assessment centres. Plumbley (1985) describes the purpose of group selection methods as being to provide evidence about the candidate’s ability to:

- get on with others;

- influence others and the way they do this;

- express themselves verbally;

- think clearly and logically;

- argue from past experience and apply themselves to a new problem;

- identify the type of role they play in group situations.

These features are difficult on the whole to identify using other selection methods and one of the particular advantages of group selection methods is that they provide the selector with examples of behaviour on which to select. When future job performance is being considered it is behaviour in the job that is critical, and so selection using group methods can provide direct information on which to select rather than indirect verbal information or test results. The increasing use of competencies and behavioural indicators, as a way to specifiy selection criteria, ties in well with the use of group methods.

There is a range of group exercises that can be used including informal discussion of a given topic, role plays and groups who must organise themselves to solve a problem within time limits which may take the form of a competitive business game, case study or physical activity.

Group selection methods are most suitable for management, graduate and sometimes supervisory posts. One of the difficulties with group selection methods is that it can be difficult to assess an individual’s contribution, and some people may be unwilling to take part.

Assessment centres

Assessment centres incorporate multiple selection techniques, and group selection methods outlined above form a major element, together with other work-simulation exercises such as in-basket tasks, psychological tests, a variety of interviews and presentations. Assessment centres are used to assess, in depth, a group of broadly similar applicants, using a set of competencies required for the post on offer and a series of behavioural statements which indicate how these competencies are played out in practice. Even assuming that the competencies for the job in question have already been identified, assessment centres require a lengthy design process to select the appropriate activities so that every competency will be measured via more than one task. Assessment centres have been proven to be one of the most effective ways of selecting candidates – this is probably due, as Suff (2005b) notes, to the use of multiple measures, multiple assessors and predetermined assessment criteria.

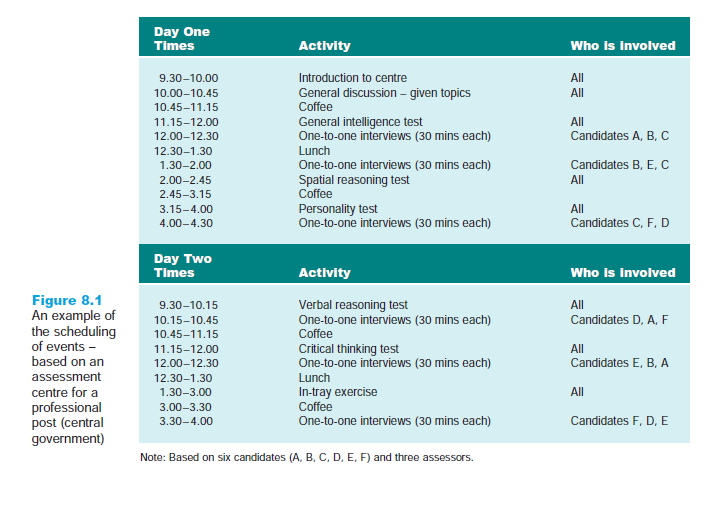

A matrix is usually developed to show how the required competencies and the activities link together. In terms of running the centre sufficient well-trained assessors will be needed, usually based on the ratio of one assessor for two candidates to ensure that the assessor can observe each candidate sufficiently carefully. Lists of competencies and associated behaviours will need to be drawn up as checklists and a careful plan will need to be made of how each candidate will move around the different activities – an example of which is found in Figure 8.1. Clearly candidates will need to be very well briefed both before and at the start of the centre.

At the end of the procedure the assessors have to come to agreement on a cumulative rating for each individual, related to job requirements, taking into account all the selection activities. The procedure as a whole can then be validated against job performance rather than each separate activity. The predictive validities from such procedures are not very consistent, but there is a high ‘face validity’ – a feeling that this is a fairer way of selecting people. Reliability can also be improved by the quality of assessor training, careful briefing of assessors and a predetermined structured approach to marking. The chief disadvantages of these selection methods are that they are a costly and timeconsuming procedure, for both the organisation and the candidates. The time commitment is extended by the need to give some feedback to candidates who have been through such a long procedure which involves psychological assessment – although

feedback is still not always available for candidates. There is evidence of increasing use of assessment centres and CIPD (2006) reports that 48 per cent of organisations in its survey used such centres for selection. Some organisations have been improving their centres (see IRS 2002b) by making the activities more connected or by using longer simulations or scenarios which are a reflection of real-life experience on the job, and are carrying out testing separately from the centre. Some are assessing candidates against the values of the company rather than a specific job, in view of the rapid change in the nature of jobs, and others, such as Britvic, are running a series of assessment centres which candidates must attend, rather than only one. A helpful text relating competency profiles and assessment centre activities is Woodruffe (2000) and IDS (2005) provides examples of different company experiences.

1.9. Work sampling/portfolios

Work sampling of potential candidates for permanent jobs can take place by assessing candidates’ work in temporary posts or on government training schemes in the same organisation. For some jobs, such as photographers and artists, a sample of work in the form of a portfolio is expected to be presented at the time of interview. Kanter (1989) suggests that managers and professionals should also be developing portfolios of their work experiences and achievements as one way of enhancing their employability.

1.10. References

One way of informing the judgement of managers who have to make employment offers to selected individuals is the use of references. Candidates provide the names of previous employers or others with appropriate credentials and then prospective employers request them to provide information. Reference checking is increasing as organisations react to scandals in the media and aim to protect themselves from rogue applicants (IRS 2002c). There are two types: the factual check and the character reference.

The factual check

The factual check is fairly straightforward as it is no more than a confirmation of facts that the candidate has presented. It will normally follow the employment interview and decision to offer a post. It simply confirms that the facts are accurate. The knowledge that such a check will be made – or may be made – will help focus the mind of candidates so that they resist the temptation to embroider their story.

The character reference

The character reference is a very different matter. Here the prospective employer asks for an opinion about the candidate before the interview so that the information gained can be used in the decision-making phases. The logic of this strategy is impeccable: who knows the working performance of the candidate better than the previous employer? The wisdom of the strategy is less sound, as it depends on the writers of references being excellent judges of working performance, faultless communicators and – most difficult of all – disinterested. The potential inaccuracies of decisions influenced by character references begin when the candidate decides who to cite. They will have some freedom of choice and will clearly choose someone from whom they expect favourable comment,

perhaps massaging the critical faculties with such comments as: ‘I think references are going to be very important for this job’ or ‘You will do your best for me, won’t you?’

1.11. Other methods

A number of other less conventional methods such as physiognomy, phrenology, body language, palmistry, graphology and astrology have been suggested as possible selection methods. While these are fascinating to read about there is little evidence to suggest that they could be used effectively. Thatcher (1997) suggests that the use of graphology is around 10 per cent in Holland and Germany and that it is regularly used in France; in the UK he found nine per cent of small firms (with fewer than 100 employees), one per cent of medium-sized firms (100-499 employees) and five per cent of larger firms used graphology as a selection method. In 1990 Fowler suggested that the extent of use of graphology is much higher in the UK than reported figures indicate, as there is some reluctance on the part of organisations to admit that they are using graphology for selection purposes. There are also concerns about the quality of graphologists – who can indeed set themselves up with no training whatsoever. The two main bodies in this field in the UK are the British Institute of Graphology and the International Graphology Association and both these organisations require members to gain qualifications before they can practise.

2. FINAL SELECTION DECISION MAKING

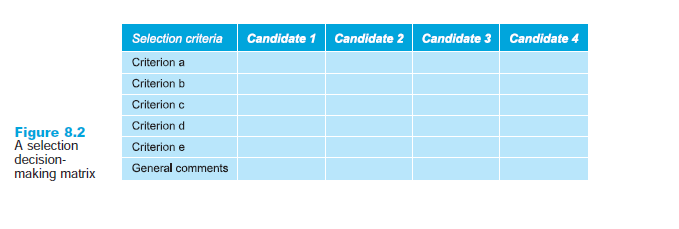

The selection decision involves measuring the candidates individually against the selection criteria defined in the person specification, and not against each other. A useful tool to achieve this is the matrix in Figure 8.2. This is a good method of ensuring that every candidate is assessed against each selection criterion and in each box in the matrix the key details can be completed. The box can be used whether a single selection method was used or multiple methods. If multiple methods were used and contradictory information is found against any criterion, this can be noted in the decision-making process.

When more than one selector is involved there is some debate about how to gather and use the information and judgement of each selector. One way is for each selector to assess the information collected separately, and then for all selectors to meet to discuss assessments. When this approach is used, there may be some very different assessments, especially if the interview was the only selection method used. Much heated and timeconsuming debate can be generated, but the most useful aspect of this process is sharing the information in everyone’s matrix to understand how judgements have been formed. This approach is also helpful in training interviewers.

An alternative approach is to fill in only one matrix, with all selectors contributing. This may be quicker, but the drawback is that the quietest member may be the one who has all the critical pieces of information. There is a risk that all the information may not be contributed to the debate in progress. Iles (1992), referring to assessment centre decisions, suggests that the debate itself may not add to the quality of the decision, and that taking the results from each selector and combining them is just as effective.

3. VALIDATION OF SELECTION PROCEDURES

We have already mentioned how test scores may be validated against eventual job performance for each individual in order to discover whether the test score is a good predictor of success in the job. In this way we can decide whether the test should be used as part of the selection procedure. The same idea can be applied to the use of other individual or combined selection methods.

The critical information that is important for determining validity is the selection criteria used, the selection processes used, an evaluation of the individual at the time of selection and current performance of the individual.

Unfortunately we are never in a position to witness the performance of rejected candidates and compare this with those we have employed. However, if a group of individuals are selected at the same time, for example, graduate trainees, it will be unlikely that they were all rated equally highly in spite of the fact that they were all considered employable. It is useful for validation purposes if a record is made of the scores that each achieved in each part of the selection process. Test results are easy to quantify, and for interview results a simple grading system can be devised.

Current performance includes measures derived from the job description, together with additional performance measures:

- Measures from the job description: quantitative measures such as volume of sales, accuracy, number of complaints and so on may be used, or qualitative measures such as relations with customers and quality of reports produced.

- Other measures: these may include appraisal results, problems identified, absence data and, of course, termination.

Current performance is often assessed in an intuitive, subjective way, and while this may sometimes be useful it is no substitute for objective assessment.

Selection ratings for each individual can be compared with eventual performance over a variety of time periods. Large discrepancies between selection and performance ratings point to further investigation of the selection criteria and methods used. The comparison of selection rating and performance rating can also be used to compare the appropriateness of different selection criteria, and the usefulness of different selection methods.

Source: Torrington Derek, Hall Laura, Taylor Stephen (2008), Human Resource Management, Ft Pr; 7th edition.

I’m not sure where you are getting your information, but great topic. I needs to spend some time learning more or understanding more. Thanks for excellent info I was looking for this information for my mission.