1. HUMAN RESOURCE MANAGEMENT FOR THE TWENTY- FIRST CENTURY

Businesses are diverse. Prisons, restaurants, oil companies, corner shops, fire brigades, churches, hotel chains, hospitals, schools, newspapers, charities, doctors’ and dentists’ surgeries, professional sports teams, airlines, barristers’ chambers and universities are all businesses in the sense that they have overall corporate missions to deliver and these have to be achieved within financial constraints. They all need to have their human resources managed, no matter how much some of the resourceful humans may resent aspects of the management process which limit their individual freedom of action.

Managing resourceful humans requires a constant balancing between meeting the human aspirations of the people and meeting the strategic and financial needs of the business. At times the balance can shift too far in one direction. Through the 1960s and 1970s the human aspirations of senior people in companies and public sector operations tended to produce large staffs, with heavyweight, hierarchical bureaucracies and stagnant businesses. One consultancy in the 1970s produced monthly comparative data measuring company success in terms of profitability and the number of employees – the more the better. At the same time the aspirations of employees lower down in the bureaucracy tended to maintain the status quo and a concentration on employee benefits that had scant relevance to business effectiveness. By the end of the twentieth century financial imperatives had generated huge reactions to this in the general direction of ‘downsizing’ or reducing the number of people employed to create businesses that were lean, fit and flexible. Hierarchies were ‘delayered’ to reduce numbers of staff and many functions were ‘outsourced’, so as to simplify the operation of the business, concentrating on core expertise at the expense of peripheral activities, which were then bought in as needed from consultants or specialist suppliers. Reducing headcount became a fashionable criterion for success.

By the beginning of the twenty-first century the problems of the scales being tipped so considerably towards rationalisation were beginning to show. Businesses became more than slim; some became anorexic. Cost cutting achieved impressive short-tem results, but it cannot be repeated year after year without impairing the basic viability of the business. Steadily the number of problem cases mounted. In Britain there was great public discussion about problems with the national rail network and the shortage of skilled staff to carry out maintenance and repairs or the lack of trained guards.

HR managers need to be particularly aware of the risks associated with cost cutting, as they may be the greatest culprits. The British National Health Service has long been criticised for inefficient use of resources, so large numbers of managers and administrators have been recruited to make things more efficient. Many of these new recruits are HR people who may be perceived by health professionals as creating inefficient and costly controls at the expense of employing more health professionals. We are not suggesting that these criticisms are necessarily justified, but there are undoubtedly situations in which the criticisms are justified.

There is now a move towards redressing that balance in search for an equilibrium between the needs for financial viability and success in the marketplace on the one hand and the need to maximise human capital on the other.

2. BUSINESSES, ORGANISATIONS AND HUMAN RESOURCE MANAGEMENT

Most books on management and the academic study of management use the term ‘organisation’ as the classifier: organisational behaviour, organisational psychology, organisational sociology and organisation theory are standard terms because they focus on the interaction between the organisation as an entity and its people or with the surrounding society. So far we have used the word ‘business’. We will not stick to this throughout the book, but we have used it to underline the fact that HR people are concerned with the management of resourceful humans not employed within the organisation as well as those who are. The above criticism of NASA’s complacency was because they had lost the sense of ownership and responsibility for a human capital input simply because the people were employed by a different organisation. HR people have to be involved in the effective management of all the people of the business, not only those who are directly employed within the organisation itself. We need to remember that organisation is a process as well as an entity.

Human resource managers administer the contract of employment, which is the legal basis of the employment relationship, but within that framework they also administer a psychological contract for performance. To have a viable business the employer obviously requires those who do its work to produce an appropriate and effective performance and the performance may come from employees, but is just as likely to come from non-employees. A business which seeks to be as lean and flexible as it can needs to reduce long-term cost commitments and focus its efforts on the activities which are the basis of its competitive advantage. It may be wise to buy in standard business services, as well as expertise, from specialist providers. Performance standards can be unambiguously agreed and monitored (although they rarely are), while the contract can be ended a great deal more easily than is the case with a department full of employees.

We refer to a contract for performance because both parties have an interest in performance. The employer needs it from the employee, but an employee also has a psychological need to perform, to do well and to fulfil personal needs that for many can best be met in the employment context. Schoolteachers cannot satisfy their desire to teach without a school to provide premises, equipment and pupils. A research chemist can do little without a well-equipped laboratory and qualified colleagues; very few coach drivers can earn their living unless someone else provides the coach.

3. DEFINING HUMAN RESOURCE MANAGEMENT

The term ‘human resource management’ is not easy to define. This is because it is commonly used in two different ways. On the one hand it is used generically to describe the body of management activities covered in books such as this. Used in this way HRM is really no more than a more modern and supposedly imposing name for what has long been labelled ‘personnel management’. On the other hand, the term is equally widely used to denote a particular approach to the management of people which is clearly distinct from ‘personnel management’. Used in this way ‘HRM’ signifies more than an updating of the label; it also suggests a distinctive philosophy towards carrying out people-oriented organisational activities: one which is held to serve the modern business more effectively than ‘traditional’ personnel management. We explore the substance of these two meanings of human resource management in the following paragraphs, referring to the first as ‘HRM mark 1’ and the second as ‘HRM mark 2’.

3.1. HRM mark 1: the generic term

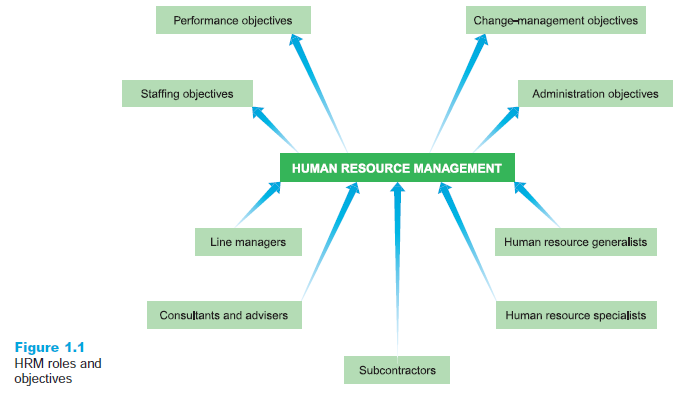

The role of the human resource functions is explained by identifying the key objectives to be achieved. Four objectives form the foundation of all HR activity.

Staffing objectives

Human resource managers are first concerned with ensuring that the business is appropriately staffed and thus able to draw on the human resources it needs. This involves designing organisation structures, identifying under what type of contract different groups of employees (or subcontractors) will work, before recruiting, selecting and developing the people required to fill the roles: the right people, with the right skills to provide their services when needed. There is a need to compete effectively in the employment market by recruiting and retaining the best, affordable workforce that is available. This involves developing employment packages that are sufficiently attractive to maintain the required employee skills levels and, where necessary, disposing of those judged no longer to have a role to play in the organisation. The tighter a key employment market becomes, the harder it is to find and then to hold on to the people an organisation needs in order to compete effectively. In such circumstances increased attention has to be given to developing competitive pay packages, to the provision of valued training and development opportunities and to ensuring that the experience of working in the organisation is, as far as is possible, rewarding and fulfilling.

Performance objectives

Once the required workforce is in place, human resource managers seek to ensure that people are well motivated and committed so as to maximise their performance in their different roles. Training and development has a role to play, as do reward systems to maximise effort and focus attention on performance targets. In many organisations, particularly where trade unions play a significant role, human resource managers negotiate improved performance with the workforce. The achievement of performance objectives also requires HR specialists to assist in disciplining employees effectively and equitably where individual conduct and/or performance standards are unsatisfactory. Welfare functions can also assist performance by providing constructive assistance to people whose performance has fallen short of their potential because of illness or difficult personal circumstances. Last but not least, there is the range of employee involvement initiatives to raise levels of commitment and to engage employees in developing new ideas. It is increasingly recognised that a key determinant of superior competitive performance is a propensity on the part of an organisation’s employees to demonstrate discretionary effort. Essentially this means that they choose to go further in the service of their employer than is strictly required in their contracts of employment, working longer hours perhaps, working with greater enthusiasm or taking the initiative to improve systems and relationships. Willingness to engage in such behaviour cannot be forced by managers. But they can help to create an environment in which it is more likely to occur.

Change-management objectives

A third set of core objectives in nearly every business relates to the role played by the HR function in effectively managing change. Frequently change does not come along in readily defined episodes precipitated by some external factor. Instead it is endemic and well-nigh continuous, generated as much by a continual need to innovate as from definable environmental pressures. Change comes in different forms. Sometimes it is merely structural, requiring reorganisation of activities or the introduction of new people into particular roles. At other times cultural change is sought in order to alter attitudes, philosophies or long-present organisational norms. In any of these scenarios the HR function can play a central role. Key activities include the recruitment and/or development of people with the necessary leadership skills to drive the change process, the employment of change agents to encourage acceptance of change and the construction of reward systems which underpin the change process. Timely and effective employee involvement is also crucial because ‘people support what they help to create’.

Administration objectives

The fourth type of objective is less directly related to achieving competitive advantage, but is focused on underpinning the achievement of the other forms of objective. In part it is simply carried out in order to facilitate an organisation’s smooth running. Hence there is a need to maintain accurate and comprehensive data on individual employees, a record of their achievement in terms of performance, their attendance and training records, their terms and conditions of employment and their personal details. However, there is also a legal aspect to much administrative activity, meaning that it is done because the business is required by law to comply. Of particular significance is the requirement that payment is administered professionally and lawfully, with itemised monthly pay statements being provided for all employees. There is also the need to make arrangements for the deduction of taxation and national insurance, for the payment of pension fund contributions and to be on top of the complexities associated with Statutory Sick Pay and Statutory Maternity Pay, as well as maternity and paternity leave. Additional legal requirements relate to the monitoring of health and safety systems and the issuing of contracts to new employees. Accurate record keeping is central to ensuring compliance with a variety of newer legal obligations such as the National Minimum Wage and the Working Time Regulations. HR professionals often downgrade the significance of effective administration, seeking instead to gain for themselves a more glamorous (and usually more highly paid) role formulating policy and strategy. This is a short-sighted attitude. Achieving excellence (i.e. professionalism and cost effectiveness) in the delivery of the basic administrative tasks is important as an aim in itself, but it also helps the HR function in an organisation to gain and maintain the credibility and respect that are required in order to influence other managers in the organisation.

3.2. Delivering HRM objectives

The larger the organisation, the more scope there is to employ people to specialise in particular areas of HRM. Some, for example, employ employee relations specialists to look after the collective relationship between management and employees. Where there is a strong tradition of collective bargaining, the role is focused on the achievement of satisfactory outcomes from ongoing negotiations. Increasingly, however, employee relations specialists are required to provide advice about legal developments, to manage consultation arrangements and to preside over employee involvement initiatives.

Another common area of specialisation is in the field of training and development. Although much of this is now undertaken by external providers, there is still a role for in-house trainers, particularly in management development. Increasingly the term ‘consultant’ is used instead of ‘officer’ or ‘manager’ to describe the training specialist’s role, indicating a shift towards a situation in which line managers determine the training they want rather than the training section providing a standardised portfolio of courses. The other major specialist roles are in the fields of recruitment and selection, health, safety and welfare, compensation and benefits and human resource planning.

In addition to the people who have specialist roles there are many other people who are employed as human resources or personnel generalists. Working alone or in small teams, they carry out the range of HR activities and seek to achieve all the objectives outlined above. In larger businesses generalists either look after all personnel matters in a particular division or are employed at a senior level to develop policy and take responsibility for HR issues across the organisation as a whole. In more junior roles, human resource administrators and assistants undertake many of the administrative tasks mentioned earlier. It is increasingly common for organisations to separate the people responsible for undertaking routine administration and even basic advice from those employed to manage case work, to develop policies and to manage the strategic aspects of the HR role. In some cases the administrative work is outsourced to specialist providers, while in others a shared services model has been established whereby a centralised administrative function is distinguished from decentralised teams of HR advisers working as part of management teams in different divisions. Figure 1.1 summarises the roles and objectives of HRM.

Most HR practitioners working at a senior level are now professionally qualified, having secured membership of the Chartered Institute of Personnel and Development (CIPD). The wide range of elective subjects which can now be chosen by those seeking qualification through the Institute’s examinations has made it as relevant to those seeking a specialist career as to those who prefer to remain in generalist roles. However, many smaller businesses do not need, or cannot afford, HR managers at all. They may use consultants or the advisory services of university departments. They may use their bank’s computer to process the payroll, but there is still a human resource dimension to their managers’ activities.

3.3. HRM mark 2: a distinctive approach to the management of people

The second meaning commonly accorded to the term ‘human resource management’ denotes a particular way of carrying out the range of activities discussed above. Under this definition, a ‘human resource management approach’ is something qualitatively different from a ‘personnel management approach’. Commentators disagree, however, about how fundamental a shift is signified by a movement from personnel management to human resource management. For some, particularly those whose focus of interest is on the management of collective relationships at work, the rise of HRM in the last two decades of the twentieth century represented something new and very different from the dominant personnel management approach in earlier years. A particular theme in their work is the contention that personnel management is essentially workforce centred, while HRM is resource centred. Personnel specialists direct their efforts mainly at the organisation’s employees; finding and training them, arranging for them to be paid, explaining management’s expectations, justifying management’s actions, satisfying employees’ work-related needs, dealing with their problems and seeking to modify management action that could produce an unwelcome employee response. The people who work in the organisation are the starting point, and they are a resource that is relatively inflexible in comparison with other resources, like cash and materials.

Although indisputably a management function, personnel management is not totally identified with management interests. Just as sales representatives have to understand and articulate the aspirations of the customers, personnel managers seek to understand and articulate the aspirations and views of the workforce. There is always some degree of being in between management and the employees, mediating the needs of each to the other.

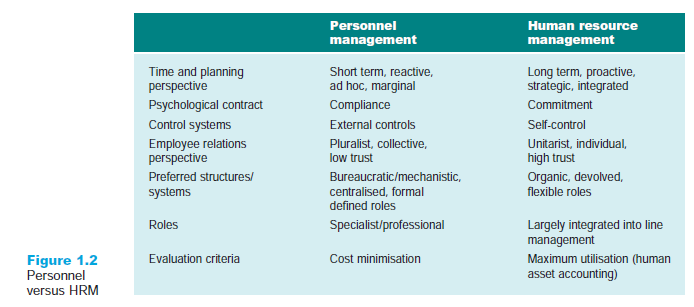

HRM, by contrast, is directed mainly at management needs for human resources (not necessarily employees) to be provided and deployed. Demand rather than supply is the focus of the activity. There is greater emphasis on planning, monitoring and control, rather than mediation. Problem solving is undertaken with other members of management on human resource issues rather than directly with employees or their representatives. It is totally identified with management interests, being a general management activity, and is relatively distant from the workforce as a whole. David Guest (1987) emphasises the differences between the two approaches in his model illustrating ‘stereotypes of personnel management and human resource management’ (see Figure 1.2).

An alternative point of view, while recognising the differences, downplays the significance of a break between personnel and human resources management. Such a conclusion is readily reached when the focus of analysis is on what HR/personnel managers actually do, rather than on the more profound developments in the specific field of collective employee relations. Legge (1989 and 1995) concludes that there is very little difference in fact between the two, but that there are some differences that are important; first, that human resource management concentrates more on what is done to managers than on what is done by managers to other employees; second, that there is a more proactive role for line managers; and, third, that there is a top management responsibility for managing culture – all factors to which we return later in the book. From this perspective, human resource management can simply be seen as the most recent mutation in a long line of developments that have characterised personnel management practice as it evolved during the last century. Below we identify four distinct stages in the historical development of the personnel management function. HRM, as described above, is a fifth. On the companion website there is a journalist’s view of contemporary HRM to which we have added some discussion questions.

4. THE EVOLUTION OF PERSONNEL AND HR MANAGEMENT

4.1. Theme 1: social justice

The origins of personnel management lie in the nineteenth century, deriving from the work of social reformers such as Lord Shaftesbury and Robert Owen. Their criticisms

of the free enterprise system and the hardship created by the exploitation of workers by factory owners enabled the first personnel managers to be appointed and provided the first frame of reference in which they worked: to ameliorate the lot of the workers. Such concerns are not obsolete. There are still regular reports of employees being exploited by employers flouting the law, and the problem of organisational distance between decision makers and those putting decisions into practice remains a source of alienation from work.

In the late nineteenth and early twentieth centuries some of the larger employers with a paternalist outlook began to appoint welfare officers to manage a series of new initiatives designed to make life less harsh for their employees. Prominent examples were the progressive schemes of unemployment benefit, sick pay and subsidised housing provided by the Quaker family firms of Cadbury and Rowntree, and the Lever Brothers’ soap business. While the motives were ostensibly charitable, there was and remains a business as well as an ethical case for paying serious attention to the welfare of employees. This is based on the contention that it improves commitment on the part of staff and leads potential employees to compare the organisation favourably vis-a-vis competitors. The result is higher productivity, a longer-serving workforce and a bigger pool of applicants for each job. It has also been argued that a commitment to welfare reduces the scope for the development of adversarial industrial relations. The more conspicuous welfare initiatives promoted by employers today include employee assistance schemes, childcare facilities and health-screening programmes.

4.2. Theme 2: humane bureaucracy

The second phase marked the beginnings of a move away from a sole focus on welfare towards the meeting of various other organisational objectives. Personnel managers began to gain responsibilities in the areas of staffing, training and organisation design. Influenced by social scientists such as F.W. Taylor (1856-1915) and Henri Fayol (18411925) personnel specialists started to look at management and administrative processes analytically, working out how organisational structures could be designed and labour deployed so as to maximise efficiency. The humane bureaucracy stage in the development of personnel thinking was also influenced by the Human Relations School, which sought to ameliorate the potential for industrial conflict and dehumanisation present in too rigid an application of these scientific management approaches. Following the ideas of thinkers such as Elton Mayo (1880-1949), the fostering of social relationships in the workplace and employee morale thus became equally important objectives for personnel professionals seeking to raise productivity levels.

4.3. Theme 3: negotiated consent

Personnel managers next added expertise in bargaining to their repertoire of skills. In the period of full employment following the Second World War labour became a scarce resource. This led to a growth in trade union membership and to what Allan Flanders, the leading industrial relations analyst of the 1960s, called ‘the challenge from below’. Personnel specialists managed the new collective institutions such as joint consultation committees, joint production committees and suggestion schemes set up in order to accommodate the new realities. In the industries that were nationalised in the 1940s, employers were placed under a statutory duty to negotiate with unions representing employees. To help achieve this, the government encouraged the appointment of personnel officers and set up the first specialist courses for them in the universities. A personnel management advisory service was also set up at the Ministry of Labour, which still survives as the first A in ACAS (the Advisory, Conciliation and Arbitration Service).

4.4. Theme 4: organisation

The late 1960s saw a switch in focus among personnel specialists, away from dealing principally with the rank-and-file employee on behalf of management, towards dealing with management itself and the integration of managerial activity. This phase was characterised by the development of career paths and of opportunities within organisations for personal growth. This too remains a concern of personnel specialists today, with a significant portion of time and resources being devoted to the recruitment, development and retention of an elite core of people with specialist expertise on whom the business depends for its future. Personnel specialists developed techniques of manpower or workforce planning. This is basically a quantitative activity, boosted by the advent of information technology, which involves forecasting the likely need for employees with different skills in the future.

4.5. Theme 5: human resource management

This has already been explained in the previous pages.

4.6. Theme 6: a ‘new HR’?

Some academic writers have recently begun to argue that we are now witnessing the beginning of a new sixth stage in the evolution of personnel/HR work. While there is by no means a clear consensus about this point of view, it is notable that leading thinkers have identified a group of trends which they believe to be sufficiently dissimilar, as a bundle, from established practices to justify, at the very least, a distinct title. Bach (2005, pp. 28-9) uses the term ‘the new HR’ to describe ‘a different trajectory’ which he believes is now clearly discernible. A number of themes are identified, including a global perspective and a strong tendency for issues relating to legal compliance to move up the HR management agenda and to occupy management time. Bach also sees as significant the increased prevalence of multi-employer networks which he calls ‘permeable organizations’. Here, instead of employees having a single, readily defined employer, there may be a number of different employers, or at least more than one organisation which exercises a degree of authority over their work. Such is the case when organisational boundaries become blurred, as they have a tendency to in the case of public-private partnerships, agency working, situations where work is outsourced by one organisation to another, joint ventures and franchises, and where strong supply chains are established consisting of smaller organisations which are wholly or very heavily reliant on the custom of a single large client corporation.

In each of these cases ‘the new HR’ amounts to a change of emphasis in response to highly significant long-term trends in the business environment. It is therefore legitimate to question the extent to which it really represents anything genuinely ‘new’ as far as HR practice is concerned. However, in addition, Bach and others draw attention to another development which can be seen as more novel and which does genuinely represent ‘a

different trajectory’. This is best summarised as an approach to the employment relationship which views employees and potential employees very much as individuals or at least small groups rather than as a single group and which seeks to engage them emotionally. It is associated with a move away from an expectation that staff will demonstrate commitment to a set of corporate values which are determined by senior management and towards a philosophy which is far more customer focused. Customers are defined explicitly as the ultimate employers and staff are empowered to act in such a way as to meet their requirements. This involves encouraging employees to empathise with customers, recruiting, selecting and appraising them according to their capacity to do so. The approach now infuses the corporate language in some organisations to the extent that HR officers refer to the staff and line managers whom they ‘serve’ as their ‘internal customers’, a client group which they aim to satisfy and which they survey regularly as a means of establishing how far this aim is in fact being achieved. The practice of viewing staff as internal customers goes further still in some organisations with the use of HR practices that borrow explicitly from the toolkit of marketing specialists. We see this in the widespread interest in employer branding exercises (see Chapter 7) where an organisation markets itself in quite sophisticated ways, not to customers and potential customers, but to employees and potential employees.

Gratton (2004) shows how highly successful companies such as Tesco go further still in categorising job applicants and existing staff into distinct categories which summarise their principal aspirations as far as their work is concerned in much the same way that organisations seek to identify distinct market segments to use when developing, designing, packaging and marketing products and services. Such approaches aim to provide an ‘employment proposition’ which it is hoped will attract the right candidates, allow the appointment of highly effective performers, motivate them to provide excellent levels of service and subsequently retain them for a longer period of time.

Lepak and Snell (2007) also note a move in HR away from ‘the management of jobs’ and towards ‘the management of people’, which includes the development of employment strategies that differ for different groups of employees. Importantly this approach recognises the capacity that most people have to become emotionally engaged in their work, with their customers, with their colleagues and hence (if to a lesser extent) with their organisations. The employment relationship is not just a transactional one in which money is earned in exchange for carrying out a set of duties competently, but also a relational one which involves emotional attachments. The ‘new HR’ understands this and seeks to manage people accordingly.

5. HRM AND THE ACHIEVEMENT OF ORGANISATIONAL EFFECTIVENESS

For the past decade the theme that has dominated the HR research agenda has been the study of links between HR practices and organisational effectiveness. Throughout the book we make reference to this research in the context of different HR activities, but it is helpful briefly to set out at the start how what happens in the field of HR impacts on an organisation’s ability to meet its objectives.

What those objectives are will vary depending on the type of organisation and its situation. For most businesses operating in the private sector the overriding long-term objective is the achievement and maintenance of competitive advantage, by which is meant a sustained period of commercial success vis-a-vis its principal competitors. For others, however, ensuring survival is a more pressing objective. In the public and voluntary sectors notions of competition and survival are increasingly present too, but here organisational effectiveness is primarily defined in terms of meeting a service need as cost efficiently as possible and to the highest achievable standard of quality. Meeting government-set targets is central to the operation of many public sector organisations, as is the requirement to ensure that the expectations of users are met as far as is possible. For all sizeable organisations there is also a need to foster a positive long-term corporate reputation. Developing such a reputation can take many years to achieve, but without care it can be lost very quickly with very damaging results. In particular organisations need to maintain a strong reputation for sound management in the financial markets. This enables them to raise money with relative ease when they need to and also helps to ensure that managers of investment funds and financial advisers see them or their shares as desirable places to put their clients’ money. The maintenance of a positive reputation in the media is also an important objective as this helps to maintain and grow the customer base. In this context corporate ethics and social responsibility are increasingly significant because they are becoming more prominent factors in determining the purchasing decisions of consumers. The HR function should play a significant role in helping to achieve each of these dimensions of organisational effectiveness.

The contribution of the HR function to gaining competitive advantage involves achieving the fundamental aims of an organisation in the field of people management more effectively and efficiently than competitor organisations. These aims were discussed above – mobilising a workforce, maximising its performance, managing change effectively and striving to achieve excellence in administration.

The contribution of the HR function to maintaining competitive advantage involves recognising the significance of the organisation’s people as an effective barrier preventing would-be rivals from expanding their markets into territory that the organisation holds. The term human capital is more and more used in this context to signify that the combined knowledge and experience of an organisation’s staff is a highly significant source of competitive advantage largely because it is difficult for competitors to replicate easily. Attracting, engaging, rewarding, developing and retaining people effectively is thus vital. Failing to do so enables accumulated human capital to leak away into the hands of competitors, reducing the effectiveness of commercial defences and making it harder to maintain competitive advantage.

Fostering a positive reputation among would-be investors, financial advisers and financial journalists is also an aspect of organisational effectiveness to which the HR function makes a significant contribution. Key here is the need to reassure those whose job it is to assess the long-term financial viability of the organisation that it is competently managed and is well placed to meet the challenges that lie ahead in both the short and the longer term. The ability to attract and retain a strong management team is central to achieving this aspect of organisational effectiveness, as is the ability of the organisation to plan for the future by having in place effective succession planning arrangements and robust systems for the development of the skills and knowledge that will be key in the future. Above all, financial markets need to be assured that the organisation is stable and is thus a safe repository for investors’ funds. The work of Stevens and his colleagues (2005) is helpful in this context. They conceive of the whole human resource contribution in terms of the management of risk, the aim being to ensure that an organisation ‘balances the maximisation of opportunities and the minimisation of risks’.

Finally, the HR function also plays a central role in building an organisation’s reputation as an ethically or socially responsible organisation. This happens in two distinct ways. The first involves fostering an understanding of and commitment to ethical conduct on the part of managers and staff. It is achieved by paying attention to these objectives in recruitment campaigns, in the criteria adopted for the selection of new employees and the promotion of staff, in the methods used to develop people and in performance management processes. The second relates to the manner in which people are managed. A poor ethical reputation can be gained simply because an organisation becomes known for treating its staff poorly. In recent years well-known fast food chains in the UK have suffered because of their use of zero hours contracts, while several large multinationals have had their reputations stained by stories in the media about the conditions under which their employees in developing countries are required to work.

Source: Torrington Derek, Hall Laura, Taylor Stephen (2008), Human Resource Management, Ft Pr; 7th edition.

Thank you for the auspicious writeup. It if truth be told was once a amusement account it. Glance complicated to more brought agreeable from you! By the way, how could we communicate?

Utterly indited subject matter, thanks for information .