Another aspect of management communication concerns the organization as a whole. Organization-wide communications typically flow in three directions—downward, up- ward, and horizontally. Managers are responsible for establishing and maintaining formal channels of communication in these three directions. Managers also use informal channels, which means they get out of their offices and mingle with employees.

1. FORMAL COMMUNICATION CHANNELS

Formal communication channels flow within the chain of command or task responsi- bility defined by the organization. The three formal channels and the types of information conveyed in each are illustrated in Exhibit 13.5.38 Downward and upward communications are the primary forms of communication used in most traditional, vertically organized companies. However, many of today’s organizations emphasize horizontal communica- tion, with people continuously sharing information across departments and levels.

Electronic communication such as e-mail and instant messaging have made it easier than ever for information to flow in all directions. For example, the U.S. Army is using technology to rapidly transmit communications about weather conditions, the latest intel- ligence on the insurgency, and so forth to lieutenants in the field in Iraq. Similarly, the Navy uses instant messaging to communicate within ships, across Navy divisions, and even back to the Pentagon in Washington. “Instant messaging has allowed us to keep our crew members on the same page at the same time,” says Lt. Cmdr. Mike Houston, who oversees the Navy’s communications program. “Lives are at stake in real time, and we’re seeing a new level of communication and readiness.”39

Downward Communication. The most familiar and obvious flow of formal communication, downward communication, refers to the messages and information sent from top management to subordinates in a downward direction.

Managers can communicate downward to employees in many ways. Some of the most common are through speeches, messages in company newsletters, e-mail, information leaf- lets tucked into pay envelopes, material on bulletin boards, and policy and procedures manuals. Managers sometimes use creative approaches to downward communication to make sure employees get the message. Mike Olson, plant manager at Ryerson Midwest Coil Processing, noticed that workers were dropping expensive power tools, so he hung price tags on the tools to show the replacement cost. Employees solved the problem by finding a way to hook up the tools so they wouldn’t be dropped. Olson’s symbolic commu- nication created a climate of working together for solutions.40

Managers also have to decide what to communicate about. It is impossible for managers to communicate with employees about everything that goes on in the organization, so they have to make choices about the important information to communicate.41 Unfortunately, many U.S. managers could do a better job of effective downward communication. The re- sults of one survey found that employees want open and honest communication about both the good and the bad aspects of the organization’s performance. But when asked to rate their company’s communication effectiveness on a scale of 0 to 100, the survey respondents’ score averaged 69. In addition, a study of 1,500 managers, mostly at first and second management levels, found that 84 percent of these leaders perceive communication as one of their most important tasks, yet only 38 percent believe they have adequate communications skills.42

Managers can do a better job of downward communication by focusing on specific areas that require regular communication. Recall our discussion of purpose-directed communi- cation from early in this chapter. Downward communication usually encompasses these five topics:

- Implementation of goals and strategies. Communicating new strategies and goals provides information about specific targets and expected behaviors. It gives direction for lower levels of the organization. Example: “The new quality campaign is for real. We must improve product quality if we are to survive.”

- Job instructions and rationale. These directives indicate how to do a specific task and how the job relates to other organizational activities. Example: “Purchasing should order the bricks now so the work crew can begin construction of the building in two weeks.”

- Procedures and practices. These messages define the organization’s policies, rules, regula- tions, benefits, and structural arrangements. Example: “After your first 90 days of em- ployment, you are eligible to enroll in our company-sponsored savings plan.”

- Performance feedback. These messages appraise how well individuals and departments are doing their jobs. Example: “Joe, your work on the computer network has greatly im- proved the efficiency of our ordering process.”

- Indoctrination. These messages are designed to motivate employees to adopt the compa- ny’s mission and cultural values and to participate in special ceremonies, such as picnics and United Way campaigns. Example: “The company thinks of its employees as family and would like to invite everyone to attend the annual picnic and fair on March 3.”

A major problem with downward communication is drop off, the distortion or loss of message content. Although formal communications are a powerful way to reach all em- ployees, much information gets lost—25 percent or so each time a message is passed from one person to the next. In addition, the message can be distorted if it travels a great distance from its originating source to the ultimate receiver. The following is a tragic historical example:

A reporter was present at a hamlet burned down by the U.S. Army 1st Air Cavalry Division in 1967. Investigations showed that the order from the Division headquarters to the brigade was: “On no occasion must hamlets be burned down.”

The brigade radioed the battalion: “Do not burn down any hamlets unless you are absolutely convinced that the Viet Cong are in them.”

The battalion radioed the infantry company at the scene: “If you think there are any Viet Cong in the hamlet, burn it down.”

The company commander ordered his troops: “Burn down that hamlet.”43

Information drop off cannot be completely avoided, but the techniques described in the previous sections can reduce it substantially. Using the right communication channel, con- sistency between verbal and nonverbal messages, and active listening can maintain com- munication accuracy as it moves down the organization.

Upward Communication. Formal upward communication includes mes- sages that flow from the lower to the higher levels in the organization’s hierarchy. Most organizations take pains to build in healthy channels for upward communication. Employ- ees need to air grievances, report progress, and provide feedback on management initia- tives. Coupling a healthy flow of upward and downward communication ensures that the communication circuit between managers and employees is complete.44 Five types of information communicated upward are the following:

- Problems and exceptions. These messages describe serious problems with and exceptions to routine performance to make senior managers aware of difficulties. Example: “The printer has been out of operation for two days, and it will be at least a week before a new one ”

- Suggestions for improvement. These messages are ideas for improving task-related proce- dures to increase quality or efficiency. Example: “I think we should eliminate step 2 in the audit procedure because it takes a lot of time and produces no results.”

- Performance reports. These messages include periodic reports that inform management how individuals and departments are performing. Example: “We completed the audit report for Smith & Smith on schedule but are one week behind on the Jackson report.”

- Grievances and disputes. These messages are employee complaints and conflicts that travel up the hierarchy for a hearing and possible resolution. Example: “The manager of operations research cannot get the cooperation of the Lincoln plant for the study of machine ”

- Financial and accounting information. These messages pertain to costs, accounts receiv- able, sales volume, anticipated profits, return on investment, and other matters of interest to senior managers. Example: “Costs are 2 percent over budget, but sales are 10 percent ahead of target, so the profit picture for the third quarter is excellent.”

Many organizations make a great effort to facilitate upward communication. Mechanisms include suggestion boxes, employee surveys, open-door policies, management information system reports, and face-to-face conversations between workers and executives. Consider how one entrepreneur keeps the upward communication flowing.

In today’s fast-paced world, many managers find it hard to maintain constant commu- nication. Ideas such as the Five-Fifteen help keep information flowing upward so managers get feedback from lower levels.

Despite these efforts, however, barriers to accurate upward communication exist. Man-agers might resist employee feedback because they don’t want to hear negative information, or employees might not trust managers sufficiently to push information upward.46 At The New York Times, for example, poor upward communication was partly to blame for the Jayson Blair scandal. Some people in the newsroom knew or suspected that the rising re- porter was fabricating elements of his news stories, but the envi-

ronment of separation between reporters and editors prevented the information from being transmitted upward.47 Innovative companies search for ways to ensure that information gets to top managers without distortion. A report reviewing the Blair scan- dal at the Times, for instance, recommended techniques such as cross-hierarchical meetings, office hours for managers, and in- formal brainstorming sessions among reporters and editors to improve upward communication.48 At Golden Corral, a restau- rant chain with headquarters in Raleigh, North Carolina, top managers spend at least one weekend a year in the trenches— cutting steaks, rolling silverware, setting tables, and taking out the trash. By understanding the daily routines and challenges of waiters, chefs, and other employees at their restaurants, Golden Corral executives increase their awareness of how management actions affect others.49

Horizontal Communication. Horizontal com- munication is the lateral or diagonal exchange of messages among peers or co-workers. It may occur within or across departments. The purpose of horizontal communication is not only to inform but also to request support and coordinate activities. Horizontal communication falls into one of three categories:

- Intradepartmental problem solving. These messages take place among members of the same department and concern task accomplishment. Example: “Kelly, can you help us figure out how to complete this medical expense report form?”

- Interdepartmental coordination. Interdepartmental messages facilitate the accomplishment of joint projects or tasks. Example: “Bob, please contact marketing and production and arrange a meeting to dis-cuss the specifications for the new sub-assembly. It looks like we might not be able to meet their requirements.”

- Change initiatives and improvements. These messages are designed to share information among teams and departments that can help the organization change, grow, and im- prove. Example: “We are streamlining the company travel procedures and would like to discuss them with your department.”

Horizontal communication is particularly important in learning organizations, where teams of workers are continuously solving problems and searching for better ways of doing things. Recall from Chapter 7 that many organizations build in horizontal communica- tions in the form of task forces, committees, or even a matrix or horizontal structure to en- courage coordination.

2. TEAM COMMUNICATION CHANNELS

A special type of horizontal communication is communicating in teams. Teams are the basic building block of many organizations. Team members work together to accomplish tasks, and the team’s communication structure influences both team performance and em- ployee satisfaction.

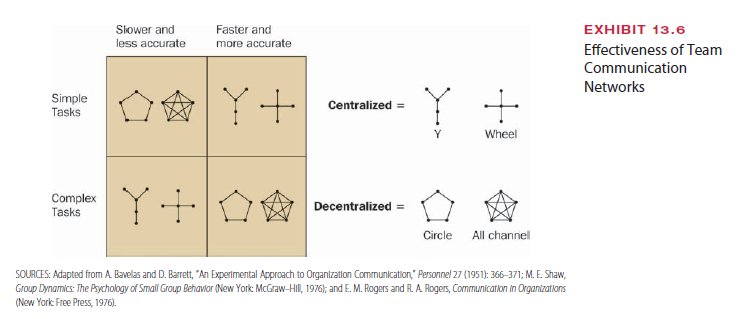

Research into team communication has focused on two characteristics: the extent to which team communications are centralized and the nature of the team’s task.50 The rela- tionship between these characteristics is illustrated in Exhibit 13.6. In a centralized network, team members must communicate through one individual to solve problems or make decisions. In a decentralized network, individuals can communicate freely with other team members. Members process information equally among themselves until all agree on a decision.51

In laboratory experiments, centralized communication networks achieved faster solu- tions for simple problems. Members could simply pass relevant information to a central person for a decision. Decentralized communications were slower for simple problems because information was passed among individuals until someone finally put the pieces together and solved the problem. However, for more complex problems, the decentralized communication network was faster. Because all necessary information was not restricted to one person, a pooling of information through widespread communications provided greater input into the decision. Similarly, the accuracy of problem solving was related to problem complexity. The centralized networks made fewer errors on simple problems but more errors on complex ones. Decentralized networks were less accurate for simple problems but more accurate for complex ones.52

The implication for organizations is as follows: In a highly competitive global environ- ment, organizations typically use teams to deal with complex problems. When team activi- ties are complex and difficult, all members should share information in a decentralized structure to solve problems. Teams need a free flow of communication in all directions.53

Teams that perform routine tasks spend less time processing information, and thus com- munications can be centralized. Data can be channeled to a supervisor for decisions, freeing workers to spend a greater percentage of time on task activities.

3. PERSONAL COMMUNICATION CHANNELS

Personal communication channels exist outside the formally authorized channels. These informal communications coexist with formal channels but may skip hierarchical levels, cutting across vertical chains of command to connect virtually anyone in the organi- zation. In most organizations, these informal channels are the primary way information spreads and work gets accomplished. Three important types of personal communication channels are personal networks, management by wandering around, and the grapevine.

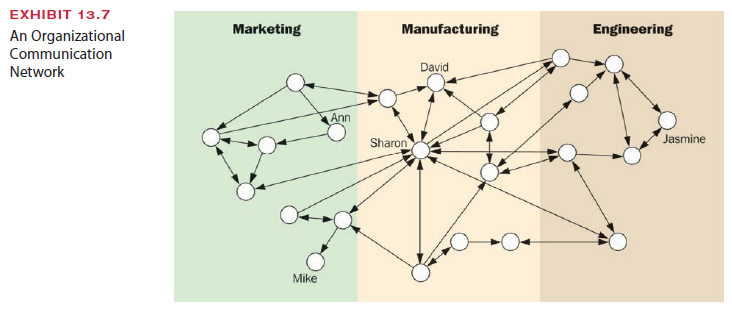

Developing Personal Communication Networks. Personal networking refers to the acquisition and cultivation of personal relationships that cross departmental, hierarchical, and even organizational boundaries.54 Smart managers con- sciously develop personal communication networks and encourage others to do so. In a communication network, people share information across boundaries and reach out to anyone who can further the goals of the team and organization. Exhibit 13.7 illustrates a communication network. Some people are central to the network, whereas others play only a peripheral role. The key is that relationships are built across functional and hierar- chical boundaries.

The value of personal networks for managers is that people who have more contacts have greater influence in the organization and get more accomplished. For example, in Exhibit 13.7, Sharon has a well-developed personal communication network, sharing information and assistance with many people across the marketing, manufacturing, and engineering departments. Contrast Sharon’s contacts with those of Mike or Jasmine. Who do you think is likely to have greater access to resources and more influence in the organization? Here are a few tips from one expert networker for building a personal communication network:55

- Build it before you need it. Smart managers don’t wait until they need something to start building a network of personal relationships—by then, it’s too late. Instead, they show genuine interest in others and develop honest connections.

- Never eat lunch alone. People who excel at networking make an effort to be visible and connect with as many people as possible. Master networkers keep their social as well as business conference and event calendars full.

- Make it win-win. Successful networking isn’t just about getting what you want; it’s also about making sure other people in the network get what they want.

- Focus on diversity. The broader your base of contacts, the broader your range of influence.

Build connections with people from as many different areas of interest as possible (both within and outside of the organization).

Most of us know from personal experience that “who you know” sometimes counts for more than what you know. By cultivating a broad network of contacts, managers can sig- nificantly extend their influence and accomplish greater results.

The Grapevine. One type of informal, person-to-person communication network that is not officially sanctioned by the organization is referred to as the grapevine.56 The grapevine links employees in all directions, ranging from the CEO through middle man- agement, support staff, and line employees. The grapevine will always exist in an organiza- tion, but it can become a dominant force when formal channels are closed. In such cases, the grapevine is actually a service because the information it provides helps makes sense of an unclear or uncertain situation. Employees use grapevine rumors to fill in information gaps and clarify management decisions. One estimate is that as much as 70 percent of all communication in a firm is carried out through its grapevine.57 The grapevine tends to be more active during periods of change, excitement, anxiety, and sagging economic condi- tions. For example, a survey by professional employment services firm Randstad found that about half of all employees reported first hearing of major company changes through the grapevine.58 Consider what happened at Jel, Inc., an auto supply firm that was under great pressure from Ford and GM to increase quality. Management changes to improve quality— learning statistical process control, introducing a new compensation system, buying a fancy new screw machine from Germany—all started out as rumors, circulating days ahead of the actual announcements, and were generally accurate.59

Surprising aspects of the grapevine are its accuracy and its relevance to the organization. About 80 percent of grapevine communications pertain to business-related topics rather than personal gossip. Moreover, from 70 to 90 percent of the details passed through a grapevine are accurate.60 Many managers would like the grapevine to be destroyed because they consider its rumors to be untrue, malicious, and harmful, which typically is not the case. Managers should be aware that almost five of every six important messages are carried to some extent by the grapevine rather than through official channels. In a survey of 22,000 shift workers in varied industries, 55 percent said they get most of their information via the grapevine.61 Smart managers understand the company’s grapevine. They recognize who’s connected to whom and which employees are key players in the informal spread of infor- mation. In all cases, but particularly in times of crisis, executives need to manage commu- nications effectively so that the grapevine is not the only source of information.62

Management by Wandering Around. The communication technique known as management by wandering around (MBWA) was made famous by the books In Search of Excellence and A Passion for Excellence.63 These books describe executives who talk directly with employees to learn what is going on. MBWA works for managers at all levels. Managers mingle and develop positive relationships with employees and learn directly from them about their department, division, or organization. The president of ARCO had a habit of visiting a district field office. Rather than schedule a big strategic meeting with the district supervisor, he would come in unannounced and chat with the lowest-level employees. In any organization, both upward and downward communications are enhanced with MBWA. Managers have a chance to describe key ideas and values to employees and, in turn, learn about the problems and issues confronting employees.

When managers fail to take advantage of MBWA, they become aloof and isolated from employees. For example, Peter Anderson, president of Ztel, Inc., a maker of televi- sion switching systems, preferred not to personally communicate with employees. He managed at arm’s length. As one manager said, “I don’t know how many times I asked Peter to come to the lab, but he stayed in his office. He wasn’t that visible to the troops.” This formal, impersonal management style contributed to Ztel’s troubles and eventual bankruptcy.64

Using the Written Word. Not all manager communication is face-to-face, or even verbal. Managers frequently have to communicate in writing, via memorandums, reports, or everyday e-mails. The memo, whether it is sent on paper or electronically, remains a primary way of communicating within companies, and e-mail has become the main way most organizations communicate with customers and clients. Yet evidence shows that the writing skills of U.S. employees and managers in general are terrible. One study found that at least a third of workers in the United States don’t have the writing skills they need to perform their jobs. A report from The National Commission on Writing says that states spend nearly $250 million a year on remedial writing training for government workers.65

Good writing matters. Consider this story told by the president of Opus Associates, a written communications consulting company: After attorney Brian Puricelli won a major case for a client, he petitioned the court to recover his fees. Magistrate Judge Jacob Hart agreed, but he deemed the petition so full or errors and misspellings that he declared it disrespectful to the court and slashed the amount due to Puricelli by nearly $30,000.66

Managers can learn to be good writers. Here are a few tips from experts on how to effectively communicate in written form:67

- Respect the reader. The reader’s time is valuable; don’t waste it with a rambling, confusing memo or e-mail that has to be read several times to try to make sense of it. Pay attention to your grammar and spelling. Sloppy writing indicates that you think your time is more important than that of your readers. You’ll lose their interest—and their respect.

- Know your point and get to it. What is the key piece of information that you want the reader to remember? Many people just sit and write, without clarifying in their own mind what it is they’re trying to say. To write effectively, know what your central point is and write to support it.

- Write clearly rather than impressively. Don’t use pretentious or inflated language, and avoid jargon. The goal of good writing for business is to be understood the first time through. State your message as simply and as clearly as possible.

- Get a second opinion. When the communication is highly important, such as a formal memo to the department or organization, ask someone you consider to be a good writer to read it before you send it. Don’t be too proud to take their advice. In all cases, read and revise the memo or e-mail a second and third time before you hit the send button.

A former manager of communication services at consulting firm Arthur D. Little Inc. has estimated that around 30 percent of all business memos and e-mails are written simply to get clarification about an earlier written communication that didn’t make sense to the reader.68 By following these guidelines, you can get your message across the first time.

Source: Daft Richard L., Marcic Dorothy (2009), Understanding Management, South-Western College Pub; 8th edition.

Wow! Thank you! I permanently wanted to write on my site something like that. Can I take a part of your post to my site?