Given these new marketing realities, what philosophy should guide a company’s marketing efforts? Let’s first review the evolution of marketing philosophies.

1. THE PRODUCTION CONCEPT

The production concept is one of the oldest concepts in business. It holds that consumers prefer products that are widely available and inexpensive. Managers of production-oriented businesses concentrate on achieving high production efficiency, low costs, and mass distribution. This orientation has made sense in developing countries such

as China, where the largest PC manufacturer, Legend (principal owner of Lenovo Group), and domestic appliances giant Haier have taken advantage of the country’s huge and inexpensive labor pool to dominate the market. Marketers also use the production concept when they want to expand the market.

2. THE PRODUCT CONCEPT

The product concept proposes that consumers favor products offering the most quality, performance, or innovative features. However, managers are sometimes caught in a love affair with their products. They might commit the “better- mousetrap” fallacy, believing a better product will by itself lead people to beat a path to their door. As many start-ups have learned the hard way, a new or improved product will not necessarily be successful unless it’s priced, distributed, advertised, and sold properly.

3. THE SELLING CONCEPT

The selling concept holds that consumers and businesses, if left alone, won’t buy enough of the organization’s products. It is practiced most aggressively with unsought goods—goods buyers don’t normally think of buying such as insurance and cemetery plots—and when firms with overcapacity aim to sell what they make, rather than make what the market wants. Marketing based on hard selling is risky. It assumes customers coaxed into buying a product not only won’t return or bad-mouth it or complain to consumer organizations but might even buy it again.

4. THE MARKETING CONCEPT

The marketing concept emerged in the mid-1950s as a customer-centered, sense-and-respond philosophy. The job is to find not the right customers for your products, but the right products for your customers. Dell doesn’t prepare a PC or laptop for its target market. Rather, it provides product platforms on which each person customizes the features he or she desires in the machine.

The marketing concept holds that the key to achieving organizational goals is being more effective than competitors in creating, delivering, and communicating superior customer value to your target markets. Harvard’s Theodore Levitt drew a perceptive contrast between the selling and marketing concepts: 56

Selling focuses on the needs of the seller; marketing on the needs of the buyer. Selling is preoccupied with the seller’s need to convert his product into cash; marketing with the idea of satisfying the needs of the customer by means of the product and the whole cluster of things associated with creating, delivering, and finally consuming it.

5. THE HOLISTIC MARKETING CONCEPT

Without question, the trends and forces that have defined the new marketing realities in the first years of the 21st century are leading business firms to embrace a new set of beliefs and practices. The holistic marketing concept is based on the development, design, and implementation of marketing programs, processes, and activities that recognize their breadth and interdependencies. Holistic marketing acknowledges that everything matters in mar- keting—and that a broad, integrated perspective is often necessary.

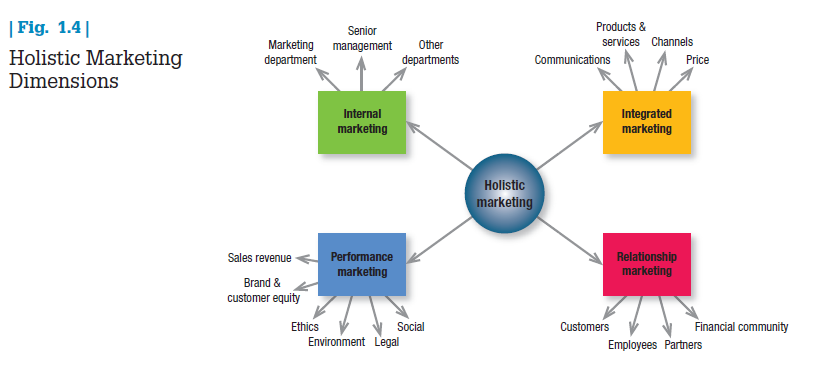

Holistic marketing thus recognizes and reconciles the scope and complexities of marketing activities. Figure 1.4 provides a schematic overview of four broad components characterizing holistic marketing: relationship marketing, integrated marketing, internal marketing, and performance marketing. We’ll examine these major themes throughout this book.

RELATIONSHIP MARKETING Increasingly, a key goal of marketing is to develop deep, enduring relationships with people and organizations that directly or indirectly affect the success of the firm’s marketing activities. Relationship marketing aims to build mutually satisfying long-term relationships with key constituents in order to earn and retain their business.

Four key constituents for relationship marketing are customers, employees, marketing partners (channels, suppliers, distributors, dealers, agencies), and members of the financial community (shareholders, investors, analysts). Marketers must create prosperity among all these constituents and balance the returns to all key stakeholders. To develop strong relationships with them requires understanding their capabilities and resources, needs, goals, and desires.

The ultimate outcome of relationship marketing is a unique company asset called a marketing network, consisting of the company and its supporting stakeholders—customers, employees, suppliers, distributors, retailers, and others—with whom it has built mutually profitable business relationships. The operating principle is simple: build an effective network of relationships with key stakeholders, and profits will follow. Thus more companies are choosing to own brands rather than physical assets, and they are subcontracting activities to firms that can do them better and more cheaply while retaining core activities at home.

Companies are also shaping separate offers, services, and messages to individual customers, based on information about their past transactions, demographics, psychographics, and media and distribution preferences. By focusing on their most profitable customers, products, and channels, these firms hope to achieve profitable growth, capturing a larger share of each customer’s expenditures by building high customer loyalty. They estimate individual customer lifetime value and design their market offerings and prices to make a profit over the customer’s lifetime.

Marketing must skillfully conduct not only customer relationship management (CRM), but partner relationship management (PRM) as well. Companies are deepening their partnering arrangements with key suppliers and distributors, seeing them as partners in delivering value to final customers so everybody benefits. IBM is a business-to-business powerhouse that has learned the value of strong customer bonds.57

IBM Having celebrated its 100th corporate anniversary in 2011, IBM is a remarkable survivor that has maintained market leadership for decades in the challenging technology industry. The company has managed to successfully evolve its business and seamlessly update the focus of its products and services numerous times in its history— from mainframes to PCs to its current emphasis on cloud computing, “big data,” and IT services. Part of the reason is that IBM’s well-trained sales force and service organization offer real value to customers by staying close to them and fully understanding their requirements. IBM often even cocreates products with customers; with the state of New York it developed a method for detecting tax evasion that reportedly saved taxpayers $1.6 billion over a seven-year period. As famed Harvard Business School professor Rosabeth Moss Kanter has noted, “IBM is not a technology company but a company solving problems using technology.”

INTEGRATED MARKETING Integrated marketing occurs when the marketer devises marketing activities and assembles marketing programs to create, communicate, and deliver value for consumers such that “the whole is greater than the sum of its parts.” Two key themes are that (1) many different marketing activities can create, communicate, and deliver value and (2) marketers should design and implement any one marketing activity with all other activities in mind. When a hospital buys an MRI machine from General Electric’s Medical Systems division, for instance, it expects good installation, maintenance, and training services to go with the purchase.

The company must develop an integrated channel strategy. It should assess each channel option for its direct effect on product sales and brand equity, as well as its indirect effect through interactions with other channel options.

All company communications also must be integrated so communication options reinforce and complement each other. A marketer might selectively employ television, radio, and print advertising, public relations and events, and PR and Web site communications so each contributes on its own and improves the effectiveness of the others. Each must also deliver a consistent brand message at every contact. Consider this award-winning campaign for Iceland.58

ICELAND Already reeling from some of the biggest losses in the global financial crisis in 2008, Iceland faced more misfortune when dormant volcano Eyjafjallajokull unexpectedly erupted in April 2010. Its enormous plumes of ash created the largest air-travel disruption since World War II, resulting in a wave of negative press and bad feelings throughout Europe and elsewhere. With tourism generating around 20 percent of the country’s foreign exchange and bookings plummeting, government and tourism officials decided to launch “Inspired by Iceland.” This campaign was based on the insight that 80 percent of visitors to Iceland recommend the destination to friends and family. The country’s own citizens were recruited to tell their stories and encourage others to join in via a Web site or Twitter, Facebook, and Vimeo. Celebrities such as Yoko Ono and Eric Clapton shared their experiences, and live concerts generated PR. Real-time Web cams across the country showed that the country was not ash-covered but green. The campaign was wildly successful—22.5 million stories were created by people all over the world—and ensuing bookings were dramatically above forecasts.

INTERNAL MARKETING Internal marketing, an element of holistic marketing, is the task of hiring, training, and motivating able employees who want to serve customers well. Smart marketers recognize that marketing activities within the company can be as important—or even more important—than those directed outside the company. It makes no sense to promise excellent service before the company’s staff is ready to provide it.

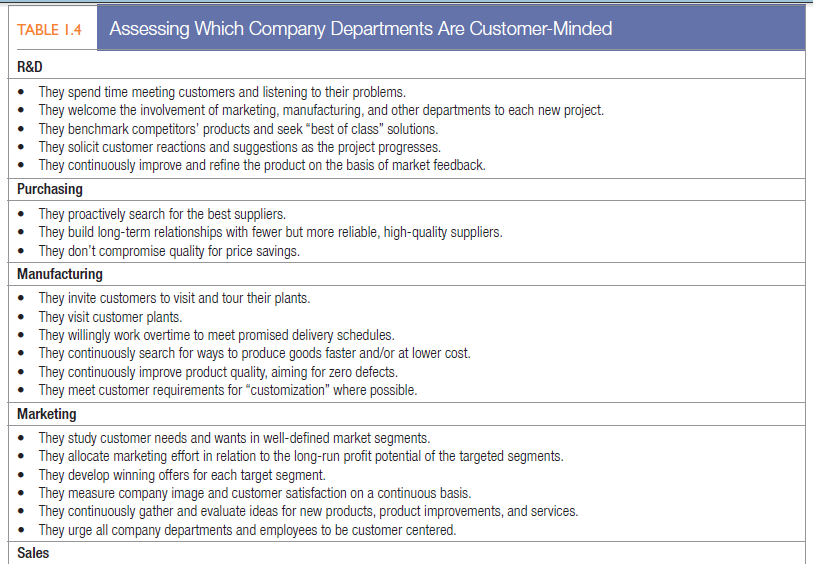

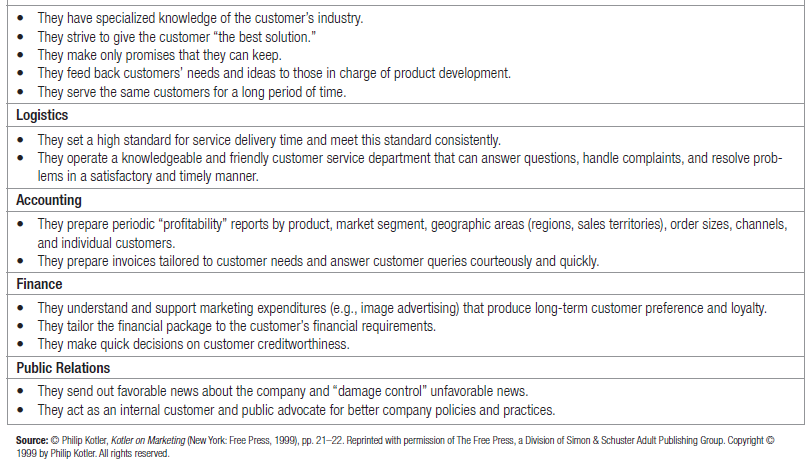

Marketing succeeds only when all departments work together to achieve customer goals (see Table 1.4): when engineering designs the right products, finance furnishes the right amount of funding, purchasing buys the right materials, production makes the right products in the right time horizon, and accounting measures profitability in the right ways. Such interdepartmental harmony can only truly coalesce, however, when senior management clearly communicates a vision of how the company’s marketing orientation and philosophy serve customers. The following example highlights some of the potential challenge in integrating marketing:

The marketing vice president of a major European airline wants to increase the airline’s traffic share. His strategy is to build up customer satisfaction by providing better food, cleaner cabins, better-trained cabin crews, and lower fares, yet he has no authority in these matters. The catering department chooses food that keeps food costs down; the maintenance department uses inexpensive cleaning services; the human resources department hires people without regard to whether they are naturally friendly; the finance department sets the fares. Because these departments generally take a cost or production point of view, the vice president of marketing is stymied in his efforts to create an integrated marketing program.

Internal marketing requires vertical alignment with senior management and horizontal alignment with other departments so everyone understands, appreciates, and supports the marketing effort.

PERFORMANCE MARKETING Performance marketing requires understanding the financial and nonfinancial returns to business and society from marketing activities and programs. As noted previously, top marketers are increasingly going beyond sales revenue to examine the marketing scorecard and interpret what is happening to market share, customer loss rate, customer satisfaction, product quality, and other measures. They are also considering the legal, ethical, social, and environmental effects of marketing activities and programs.

When they founded Ben & Jerry’s, Ben Cohen and Jerry Greenfield embraced the performance marketing concept by dividing the traditional financial bottom line into a “double bottom line” that also measured the environmental impact of their products and processes. That later expanded into a “triple bottom line” to represent the social impacts, negative and positive, of the firm’s entire range of business activities.

Many firms have failed to live up to their legal and ethical responsibilites, and consumers are demanding more responsible behavior.59 One research study reported that at least one-third of consumers around the world believed that banks, insurance providers, and packaged-food companies should be subject to stricter regulation.60

Source: Kotler Philip T., Keller Kevin Lane (2015), Marketing Management, Pearson; 15th Edition.

a cool piece of writing

I’ve read several excellent stuff here. Definitely price bookmarking for revisiting. I wonder how much attempt you set to create any such fantastic informative site.