Various policies and procedures guide the firm in recruiting, selecting, training, supervising, motivating, and evaluating sales representatives to manage its sales force (see Figure 22.3).

1. RECRUITING AND SELECTING REPRESENTATIVES

At the heart of any successful sales force are appropriately selected representatives. One survey revealed that the top 25 percent of the sales force brought in more than 52 percent of the sales. It’s a great waste to hire the wrong people. The average annual turnover rate of sales reps for all industries is almost 20 percent. Sales force turnover leads to lost sales, the expense of finding and training replacements, and often pressure on existing salespeople to pick up the slack.39

Studies have not always shown a strong relationship between sales performance on one hand and background and experience variables, current status, lifestyle, attitude, personality, and skills on the other. More effective predictors of high performance in sales are composite tests and assessment centers that simulate the working environment and assess applicants in an environment similar to the one in which they would work.40

Although scores from formal tests are only one element in a set that includes personal characteristics, references, past employment history, and interviewer reactions, they have been weighted quite heavily by companies such as IBM, Prudential, and Procter & Gamble. Gillette claims tests have reduced turnover and scores have correlated well with the progress of new reps.

2. TRAINING AND SupERVISING SALES REpRESENTATIVES

Today’s customers expect salespeople to have deep product knowledge, add ideas to improve operations, and be efficient and reliable. These demands have required companies to make a much greater investment in sales training.

New reps may spend a few weeks to several months in training. The median training period is 28 weeks in industrial-products companies, 12 in service companies, and 4 in consumer-products companies. Training time varies with the complexity of the selling task and the type of recruit. New methods of training are continually emerging, such as the use of programmed learning, distance learning, and videos. Some firms use role playing and sensitivity or empathy training to help reps identify with customers’ situations and motives.

Reps paid mostly on commission generally receive less supervision. Those who are salaried and must cover definite accounts are likely to receive substantial supervision. With multilevel selling, which Avon, Sara Lee, Virgin, and others use, independent distributors are also in charge of their own sales force selling company products. These independent contractors or reps are paid a commission not only on their own sales but also on the sales of people they recruit and train.

3. SALES REP PRODUCTIVITY

How many calls should a company make on a particular account each year? Some research suggests today’s sales reps spend too much time selling to smaller, less profitable accounts instead of focusing on larger, more profitable ones.41

NORMS FOR PROSPECT CALLS Left to their own devices, many reps will spend most of their time with current customers, who are known quantities. Reps can depend on them for some business, whereas a prospect might never deliver any. Companies therefore often specify how much time reps should spend prospecting for new accounts.42 Spector Freight wants its sales representatives to spend 25 percent of their time prospecting and stop after three unsuccessful calls. Some companies rely on a missionary sales force to create new interest and open new accounts.

USING SALES TIME EFFICIENTLY In the course of a day, reps plan, travel, wait, sell, and perform administrative tasks (writing reports and billing, attending sales meetings, and talking to others in the company about production, delivery, billing, and sales performance). It’s no wonder face-to-face selling accounts for as little as 29 percent of total working time!43 The best sales reps manage their time efficiently. Time-and-duty analysis and hour- by-hour breakdowns of activities help them understand how they spend their time and how they might increase their productivity.

Companies constantly try to improve sales force productivity.44 To cut costs, reduce time demands on their outside sales force, and leverage technological innovations, many have increased the size and responsibilities of their inside sales force.

Inside selling is less expensive and growing faster than inperson selling. Each contact made by an inside salesperson might cost a company $25 to $30 compared with $300 to $500 for a field staff person with travel expenses. Virtual meeting software such as WebEx, communication tools such as Skype, and social media sites such as LinkedIn, Facebook, and Twitter make it easier to sell with few if any face-to-face meetings. And inside sellers don’t even need to be in the office—a growing percentage work at home.45

The inside sales force frees outside reps to spend more time selling to major accounts, identifying and converting new major prospects, and obtaining more blanket orders and systems contracts. Inside salespeople spend more time checking inventory, following up orders, and phoning smaller accounts. They typically earn a salary or salary-plus-bonus pay.

SALES TECHNOLOGY The salesperson today has truly gone electronic. Not only is sales and inventory information transferred much more quickly, but specific computer-based decision support systems have been created for sales managers and sales representatives. Going online with a tablet or laptop, salespeople can prime themselves on backgrounds of clients, call up prewritten sales letters, transmit orders and resolve customer-service issues on the spot, and send samples, pamphlets, brochures, and other materials to clients.

One of the most valuable digital tools for the sales rep is the company Web site. It can help define the firm’s relationships with individual accounts and identify those whose business warrants a personal sales call. It provides an introduction to self-identified potential customers and a way to contact the seller; it might even receive the initial order.

Social media are another valuable digital selling tool. Social networking is useful in “front end” prospecting and lead qualification as well as in “back end” relationship building and management. When one B-to-B sales rep for virtual-meetings company PGi was monitoring Twitter tweets for various keywords, he noticed that someone from a company tweeted about dissatisfaction with “web conferencing.” The sales rep got in touch with the company’s CEO and was able to quickly convince him of the merits of PGi’s products, securing an agreement within a few hours.46

4. MOTIVATING SALES REPRESENTATIVES

The majority of sales representatives require encouragement and special incentives, especially those in the field who encounter daily challenges.47 Most marketers believe that the higher the salesperson’s motivation, the greater the effort and the resulting performance, rewards, and satisfaction—all of which in turn further increase motivation.

INTRINSIC VERSUS EXTRINSIC REWARDS Marketers reinforce intrinsic and extrinsic rewards of all types. One research study found the employee reward with the highest value was pay, followed by promotion, personal growth, and sense of accomplishment.48 Least valued were liking and respect, security, and recognition. In other words, salespeople are highly motivated by pay and the chance to get ahead and satisfy their intrinsic needs, and they may be less motivated by compliments and security. Some firms use sales contests to increase sales effort.49

Compensation plans may even need to vary depending on the type of salespersons: stars, core or solid performers, and laggards.50 Stars benefit from no ceiling or caps on commissions, overachievement commissions for exceeding quotas, and prize structures that allow multiple winners.51 Core performers benefit from multi-tier targets that serve as stepping stones for achievement and sales contests with prizes that vary in nature and value. Laggards respond to consistent quarterly bonuses and social pressure.52

SALES QUOTAS Many companies set annual sales quotas, developed from the annual marketing plan, for dollar sales, unit volume, margin, selling effort or activity, or product type. Compensation is often tied to degree of quota fulfillment. The company first prepares a sales forecast that becomes the basis for planning production, workforce size, and financial requirements. Management then establishes quotas for regions and territories, which typically add up to more than the sales forecast to encourage managers and salespeople to perform at their best. Even if they fail to make their quotas, the company nevertheless may reach its sales forecast.

Conventional wisdom says profits are maximized by sales reps focusing on the more important products and more profitable products. Reps are unlikely to achieve their quotas for established products when the company is launching several new products at the same time. The company may need to expand its sales force for new-product launches.

Setting sales quotas can create problems. If the company underestimates and the sales reps easily achieve their quotas, it has overpaid them. If it overestimates sales potential, the salespeople will find it very hard to reach their quotas and be frustrated or quit. Another downside is that quotas can drive reps to get as much business as possible—often ignoring the service side of the business. The company gains short-term results at the cost of l ong-term customer satisfaction. For these reasons, some companies are dropping quotas. Even hard-driving Oracle has changed its approach to sales compensation.53

ORACLE Finding sales flagging and customers griping, Oracle, the second-largest software company in the world, decided to overhaul its sales department and practices. Its rapidly expanding capabilities, with diverse applications such as human resources, supply chain, and CRM, meant one rep could no longer be responsible for selling all Oracle products to certain customers. Reorganization let reps specialize in a few particular products. To tone down the sales force’s reputation as overly aggressive, Oracle changed the commission structure from a range of 2 percent to 12 percent to a flat 4 percent to 6 percent and adopted guidelines on how to “play nice” with channels, independent software vendors (ISVs), resellers, integrators, and value-added resellers (VARs). Six principles instructed sales staff to identify and work with partners in accounts and respect their positions and the value they add in order to address partner feedback that Oracle should be more predictable and reliable.

5. EVALUATING SALES REPRESENTATIVES

We have been describing the feed-forward aspects of sales supervision—how management communicates what the sales reps should be doing and motivates them to do it. But good feed-forward requires good feedback, which means getting regular information about reps to evaluate their performance.

SOURCES OF INFORMATION The most important source of information about reps is sales reports. Additional information comes through personal observation, salesperson self-reports, customer letters and complaints, customer surveys, and conversations with other reps.

Sales reports are divided between activity plans and write-ups of activity results. The best example of the former is the salespersons work plan, which reps submit a week or month in advance to describe intended calls and routing. This report forces sales reps to plan and schedule their activities and inform management of their whereabouts. It provides a basis for comparing their plans and accomplishments, or their ability to “plan their work and work their plan.”

Many companies require representatives to develop an annual territory-marketing plan in which they outline their program for developing new accounts and increasing business from existing accounts. Sales managers study these plans, make suggestions, and use them to develop sales quotas. Sales reps write up completed activities on call reports. They also submit expense reports, new-business reports, lost-business reports, and reports on local business and economic conditions.

These reports provide raw data from which sales managers can extract key indicators of sales performance: (1) average number of sales calls per salesperson per day, (2) average sales call time per contact, (3) average revenue

per sales call, (4) average cost per sales call, (5) entertainment cost per sales call, (6) percentage of orders per hundred sales calls, (7) number of new customers per period, (8) number of lost customers per period, and (9) sales force cost as a percentage of total sales.

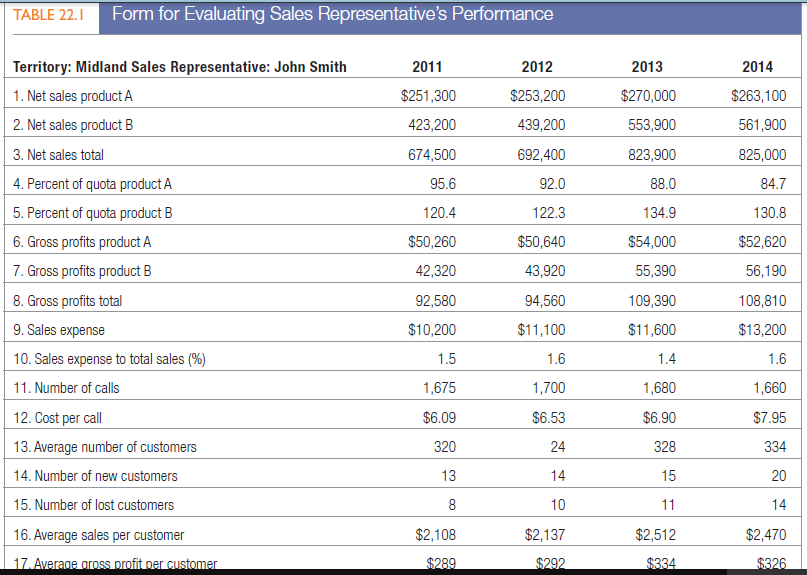

FORMAL EVALUATION The sales force’s reports along with other observations supply the raw materials for evaluation. One type of evaluation compares current with past performance. An example is shown in Table 22.1.

The sales manager can learn many things about rep John Smith from this table. Total sales increased every year (line 3). This does not necessarily mean Smith is doing a better job. The product breakdown shows he has been able to push the sales of product B further than the sales of product A (lines 1 and 2), though A is more profitable for the company. Given his quotas for the two products (lines 4 and 5), Smith could be increasing product B sales at the expense of product A sales. Although he increased total sales by $1,100 between 2013 and 2014 (line 3), gross profits on total sales actually decreased by $580 (line 8).

Sales expense (line 9) shows a steady increase, though total expense as a percentage of total sales seems to be under control (line 10). The upward trend in total dollar expense does not seem to be explained by any increase in the number of calls (line 11), though it might be related to success in acquiring new customers (line 14). Perhaps in prospecting for new customers, this rep is neglecting present customers, as indicated by an upward trend in the annual number of lost accounts (line 15).

The last two lines show the level and trend in sales and gross profits per customer. These figures become more meaningful when compared with overall company averages. If Smith’s average gross profit per customer is lower than the company’s average, he could be concentrating on the wrong customers or not spending enough time with each customer. A review of annual number of calls (line 11) shows he might be making fewer annual calls than the average salesperson. If distances in the territory are similar to those in other territories, he might not be putting in a full workday, might be poor at sales planning and routing, or might be spending too much time with certain accounts.

Even if effective in producing sales, the rep may not rate highly with customers. Success may come because competitors’ salespeople are inferior, the rep’s product is better, or new customers are always found to replace those who dislike the rep. Managers can glean customer opinions of the salesperson, product, and service by mail questionnaires or telephone calls. Sales reps can analyze the success or failure of a sales call and how they would improve the odds on subsequent calls. Their performance could be related to internal factors (effort, ability, and strategy) and/or external factors (task and luck).54

Source: Kotler Philip T., Keller Kevin Lane (2015), Marketing Management, Pearson; 15th Edition.

Magnificent website. Lots of helpful information here. I am sending it to a few pals ans also sharing in delicious. And of course, thanks on your sweat!