Evaluating the worth of a business is central to strategy implementation because numerous strategies are often implemented by acquiring other firms. In addition, some strategies, such as retrenchment and divestiture, may result in the sale of a division of an organization or of the firm itself. Thus, thousands of transactions occur each year in which businesses are bought or sold in the United States. In all these cases, it is necessary to establish the financial worth or cash value of a business to successfully implement strategies.

Corporate valuation is not an exact science; value is sometimes in the eye of the beholder. Companies desire to sell high and buy low, and negotiation normally takes place in both situations. The valuation of a firm’s worth is based on financial facts, but common sense and good judgment enter into the process because it is difficult to assign a monetary value to some factors—such as a loyal customer base, a history of growth, legal suits pending, dedicated employees, a favorable lease, a bad credit rating, or good patents—that may not be reflected in a firm’s financial statements. Also, different valuation methods will yield different totals for a firm’s worth, and no prescribed approach is best for a certain situation. Evaluating the worth of a business truly requires both qualitative and quantitative skills.

Before we examine four methods widely used for corporate valuation, let’s examine the concepts of goodwill, premium, and discount a bit further because these issues directly relate to corporate valuation. FASB Rule 142 requires companies to admit once a year if the premiums they paid for acquisitions, called goodwill, were a waste of money. Goodwill is not a good thing to have on a balance sheet. J. Crew Group Inc., for example, recently wrote down the value of the goodwill on its balance sheet by 57 percent, or $536 million. Hewlett-Packard, Boston Scientific, Frontier Communications, and Republic Services carry more goodwill on their balance sheet than their market (or book) value. This is a signal that their goodwill should be “written down,” which means “reduced and recorded as an expense on the income statement.” Jack Ciesielski, publisher of Analyst’s Accounting Observer, says, “Writing down goodwill is an admission that the company screwed up when it budgeted what an acquired firm is worth.” Sometimes it is OK to pay more for a company than its book value if the firm has technology or patents you need or economies of scale you desire or even to reduce competitive pricing pressure, but, like buying a house, paying a “premium” for a company is almost always not a good thing. Acquiring at a “discount” is far better for shareholders. Because goodwill write-down accounting rules involve projections and judgments, companies have leeway for when to write down goodwill, and by how much. If the purchase price is less than the stock price times the number of shares outstanding (rather than more), that difference is called a discount. For example, Clayton Doubilier & Rice LLC recently acquired Emergency Medical Services (EMS) Corp. for $2.9 billion, a 9.4 percent discount below EMS’s stock price of $64.00. Academic Research Capsule 8-1 addresses the premium versus discount issue.

1. When Should We Overpay to Acquire a Firm?

Scholars have long been interested in the decision-making process regarding when firms pay premiums versus discounts for acquired firms. Paying high acquisition premiums inflate a firm’s goodwill, and has often been criticized in research. Acquisition premiums the last few years have averaged 25 to 40 percent, but sometimes exceed 100 percent. Prior research suggests that high premiums generally have negative impacts on acquisition performance. Scholars have explored the how and why of excessive premium decisions to determine if overconfidence or hubris on the part of chief executive officers (CEOs) is the culprit. Specifically, Zhu recently reported that board members’ influence on premium versus discount decisions

may not always be beneficial. In particular, Zhu reports a tendency for directors to support low premiums when their average prior premium was low, but directors tend to support paying high premiums when their average prior premium was relatively high. Due to this “group bias,” Zhu questions the extent (or whether) members of a firm’s board of directors should be involved with acquisition purchase decisions.

Source: Based on Zhu, David, “Group Polarization on Corporate Boards: Theory and Evidence on Board Decisions about Acquisition Premiums,” Strategic Management Journal, 34 (2013): 800-822.

2. Corporate Valuation Methods

Four methods are often used to determine the monetary value of a company; these four methods are described below.

METHOD 1 The Net Worth Method = Total Shareholders’ Equity (SE) – (Goodwill + Intangibles)

Other terms for Total Shareholders’ Equity are Total Owners’ Equity or Net Worth, but this line item near the bottom of a balance sheet represents the sum of common stock, additional paid-in capital, and retained earnings. After calculating total SE, subtract goodwill and intangibles if these items appear as assets on the firm’s balance sheet. Whereas intangibles include copyrights, patents, and trademarks, goodwill arises only if a firm acquires another firm and pays more than the book value for that firm

METHOD 2 The Net Income Method = Net Income x Five

The second approach for measuring the monetary value of a company grows out of the belief that the worth of any business should be based largely on the future benefits its owners may derive through net profits. A conservative rule of thumb is to establish a business’s worth as five times the firm’s current annual profit. A 5-year average profit level could also be used. When using this approach, remember that firms normally suppress earnings in their financial statements to minimize taxes. Note in Table 8-11 that Method 2 results in the lowest corporate valuation of all methods for all three firms. If you were acquiring a business, this might be a good first offer, but likely Method 2 does not produce a value you would want to begin with if you are selling your business.

If a firm’s net income is negative, theoretically Method 2 yields a negative number, implying that the firm would pay you to acquire them. Of course, when you acquire another firm, you obtain all of the firm’s debt and liabilities, so theoretically this would be possible.

Method 3 Price-Earnings Ratio Method = (Stock Price ÷ EPS) x NI

To use this method, divide the market price of the firm’s common stock by the annual earnings per share (EPS) and multiply this number by the firm’s average net income for the past five years. Notice in Table 8-12 this method yields an answer close to Method 4. Algebraically, this method is identical to Method 4, if earnings and # of shares figures are taken at the same point in time.

Method 4 Outstanding Shares Method = # of Shares Outstanding x Stock Price

To use this method, simply multiply the number of shares outstanding (or issued) by the market price per share. If the purchase price is more than this amount, the additional dollars are called a premium. The outstanding shares method may also be called the market value or market capitalization or book value of the firm. The premium is a per-share dollar amount that a person or firm is willing to pay beyond the book value of the firm to control (acquire) the other company.

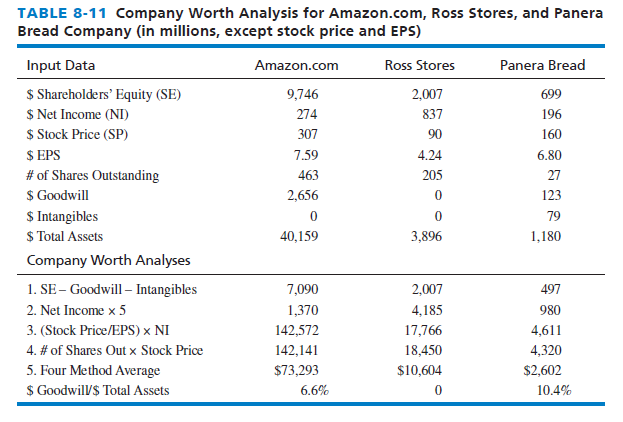

Table 8-11 provides the cash value analyses for three companies—Amazon.com, Ross Stores, and Panera Bread Company at year-end 2014. Note in Table 8-11 that Panera Bread Company’s $ Goodwill to $ Total Assets is high at 10.4 percent, indicating that a tenth of the company’s assets are “Goodwill,” which is not good.

Notice in Table 8-11 there is significant variation among the four methods used to determine cash value. For example, the worth of Amazon ranged from $1.3 billion to $142 billion. Obviously, if you were selling your company, you would seek the larger values, whereas if purchasing a company you would seek the lower values. In practice, substantial negotiation takes place in reaching a final compromise (or averaged) amount.

In addition to preparing to buy or sell a business, corporate valuation analysis is oftentimes performed when dealing with the following issues: bank loans, tax calculations, retirement packages, death of a principal, divorce, partnership agreements, and IRS audits. Practically, it is just good business to have a reasonable understanding of what a firm is worth. This knowledge protects the interests of all parties involved.

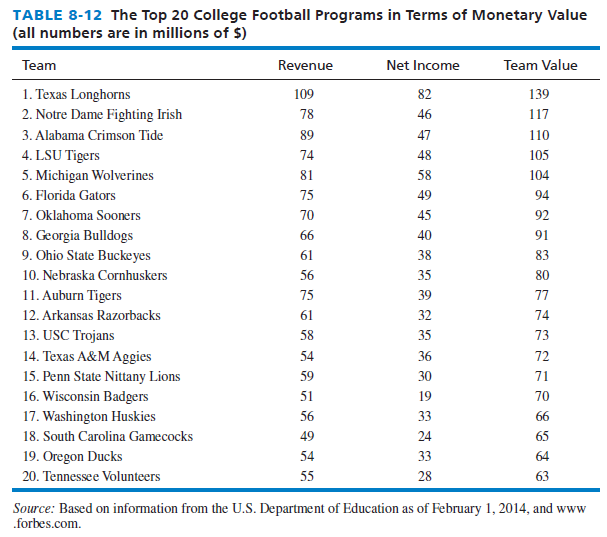

Table 8-12 provides a list of U.S. college football teams ranked in terms of their monetary value. Note that the Texas Longhorns are Number 1, followed by the Notre Dame Fighting Irish. Also observe that there are eight Southeastern Conference (SEC) teams among the top 20. In calculating the team value amounts, analysts made various cash flow adjustments, so the amounts are generally less than the “net income times five” formula described in Method 2. Net income times two (or three) is much closer to actual figures reported for the monetary value of college football programs.

Source: David Fred, David Forest (2016), Strategic Management: A Competitive Advantage Approach, Concepts and Cases, Pearson (16th Edition).

18 May 2021

18 May 2021

17 May 2021

17 May 2021

17 May 2021

17 May 2021