Brand equity is the added value endowed to products and services with consumers. It may be reflected in the way consumers think, feel, and act with respect to the brand, as well as in the prices, market share, and profitability it commands.

Marketers and researchers use various perspectives to study brand equity.24 Customer-based approaches view it from the perspective of the consumer—either an individual or an organization—and recognize that the power of a brand lies in what customers have seen, read, heard, learned, thought, and felt about the brand over time.25

Customer-based brand equity is thus the differential effect brand knowledge has on consumer response to the marketing of that brand.26 A brand has positive customer-based brand equity when consumers react more favorably to a product and the way it is marketed when the brand is identified than when it is not identified. A brand has negative customer-based brand equity if consumers react less favorably to marketing activity for the brand under the same circumstances. There are three key ingredients of customer-based brand equity.

- Brand equity arises from differences in consumer response. If no differences occur, the brand-name product is essentially a commodity, and competition will probably be based on price.

- Differences in response are a result of consumers’ brand knowledge, all the thoughts, feelings, images, experiences, and beliefs associated with the brand. Brands must create strong, favorable, and unique brand associations with customers, as have Toyota (reliability), Hallmark (caring), and Amazon.com (convenience and wide selection).

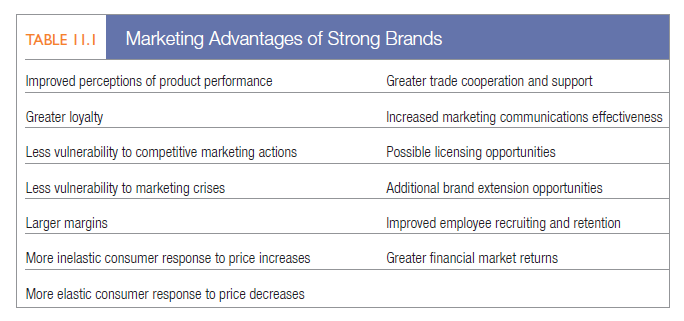

- Brand equity is reflected in perceptions, preferences, and behavior related to all aspects of the marketing of a brand. Stronger brands earn greater revenue.27 Table 11.1 summarizes some key benefits of brand equity.

The challenge for marketers is therefore ensuring customers have the right type of experiences with products, services, and marketing programs to create the desired thoughts, feelings and brand knowledge. In an abstract sense, we can think of brand equity as providing marketers with a vital strategic bridge from their past to their future.28

Marketers should also think of the marketing dollars spent on products and services each year as investments in consumer brand knowledge. The quality of that investment is the critical factor, not necessarily the quantity (beyond some threshold amount). It’s actually possible to overspend on brand building if money is not spent wisely.

Customers’ brand knowledge dictates appropriate future directions for the brand. Consumers will decide, based on what they think and feel about the brand, where (and how) they believe the brand should go and grant permission (or not) to any marketing action or program. New-product ventures such as BENGAY aspirin, Cracker Jack cereal, Frito-Lay lemonade, Fruit of the Loom laundry detergent, and Smucker’s premium ketchup all failed because consumers found them inappropriate extensions of the brand.

A brand promise is the marketer’s vision of what the brand must be and do for consumers. Virgin’s brand promise is to enter categories where customers’ needs are not well met, do different things, and do things differently, all in a way that better meets those needs. With Virgin America, the company appears to have come up with another brand winner.29

VIRGIN AMERICA After flying for only a few years, Virgin America became an award-winning airline that passengers adore and that can make money. It is not unusual for the company to receive e-mails from customers saying they actually wished their flights lasted longer! Virgin America set out to reinvent the entire travel experience, starting with an easy-to-use and friendly Web site and check-in. In flight, passengers revel in Wi-Fi, spacious leather seats, mood lighting, and in-seat food and beverage ordering through touch-screen panels. Some passengers remark that Virgin America is like “flying in an iPod or nightclub.” The brand is seeking to be positioned as “an established player featuring discount pricing and a hip, stylish customer experience for travelers.” Without a national TV ad campaign, Virgin America has relied on PR, word of mouth, social media, and exemplary customer service to create that customer experience and build the brand. To get customers more involved with the brand, Virgin America launched a digital marketing campaign offering the opportunity to upload a photo to Instagram from the flight. By tweeting the company’s Twitter account, travelers can also upload their photo onto Virgin America’s Times Square billboard or share it via their own social media accounts.

Violating a brand promise can have severe consequences. Founded in 1984, TED talks (“Technology, Entertainment, and Design”) became widely admired for their thought-provoking, leading-edge content. After deciding to let anyone apply to manage and stage local events called TEDx with relatively minor oversight, the organizers of TED saw thousands of events of varying quality spring up all over the world, leading some critics to question whether the organization was losing control of its brand.30

1. BRAND EQUITY MODELS

Although marketers agree about basic branding principles, a number of models of brand equity offer some differing perspectives. Here we highlight three more established ones.

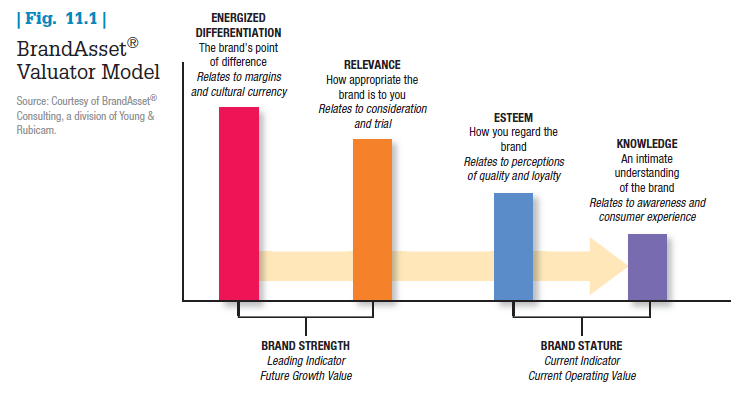

BRANDASSET® VALUATOR Advertising agency Young and Rubicam (Y&R) developed a model of brand equity called the BrandAsset® Valuator (BAV). Based on research with more than 800,000 consumers in 51 countries, BAV compares the brand equity of thousands of brands across hundreds of different categories. There are four key components—or pillars—of brand equity, according to BAV (see Figure 11.1):

- Energized differentiation measures the degree to which a brand is seen as different from others as well as its pricing power.

- Relevance measures the appropriateness and breadth of a brand’s appeal.

- Esteem measures perceptions of quality and loyalty, or how well the brand is regarded and respected.

- Knowledge measures how aware and familiar consumers are with the brand and the depth of their experience.

Energized differentiation and relevance combine to determine brand strength—a leading indicator that predicts future growth value. Esteem and knowledge together create brand stature, a “report card” of past performance and a lagging indicator of current operating value.

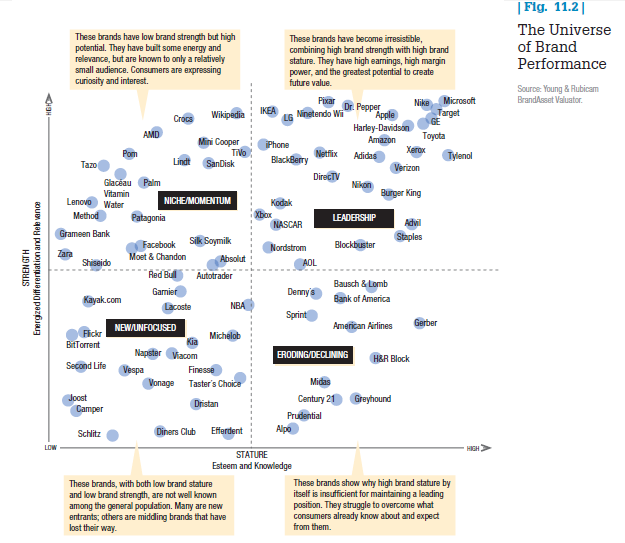

The relationships among these dimensions—a brand’s “pillar pattern”—reveal much about a brand’s current and future status. Brand strength and brand stature combine to form the power grid, depicting stages in the cycle of brand development in successive quadrants (see Figure 11.2). Strong new brands show higher levels of energized differentiation and energy than relevance, whereas both esteem and knowledge are lower still. Leadership brands show high levels on all pillars, with strength greater than stature. As strength slips, they become mass market brands. Finally, declining brands show high knowledge—evidence of past performance—a lower level of esteem, and even lower relevance and energized differentiation.

According to BAV analysis, consumers are concentrating their devotion and purchasing power on an increasingly smaller portfolio of special brands—brands with energized differentiation that keep evolving. These brands connect better with consumers—commanding greater usage loyalty and pricing power and creating greater shareholder value. Some recent insights from the BAV data are summarized in “Marketing Insight: Brand Bubble Trouble.”

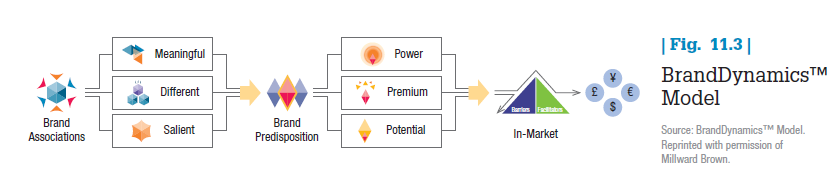

BRANDZ Marketing research consultants Millward Brown and WPP have developed the Brandz model of brand strength, at the heart of which is the BrandDynamics™ model, a system of brand equity measurements, based on Millward Brown’s Meaningfully Different Framework, that reveals a brand’s current equity and opportunities for growth (Figure 11.3).[1] BrandDynamics employs a set of simple scores that summarize a brand’s equity and are relatable directly to real world financial and business outcomes.

BrandDynamics maintain that three different types of brand associations are crucial for building customer predisposition to buy a brand—meaningful, different, and salient brand associations. The success of a brand along those three dimensions, in turn, is reflected in three important outcome measures:

- Power: a prediction of the brand’s volume share

- Premium: a brand’s ability to command a price premium relative to the category average

- Potential: the probability that a brand will grow value share

According to the model, how well a brand is activated in the marketplace and the competition that exists there will determine how strongly brand predisposition ultimately translates into sales.

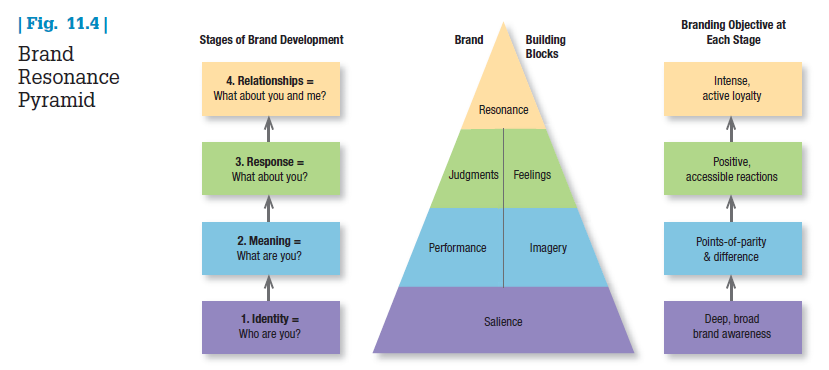

BRAND RESONANCE MODEL The brand resonance model also views brand building as an ascending series of steps, from bottom to top: (1) ensuring customers identify the brand and associate it with a specific product class or need; (2) firmly establishing the brand meaning in customers’ minds by strategically linking a host of tangible and intangible brand associations; (3) eliciting the proper customer responses in terms of brand-related judgment and feelings; and (4) converting customers’ brand responses to intense, active loyalty.

According to this model, enacting the four steps means establishing a pyramid of six “brand building blocks” as illustrated in Figure 11.4. The model emphasizes the duality of brands—the rational route to brand building is on the left side of the pyramid, and the emotional route is on the right side.31 One brand that has found much success going up both sides of the pyramid is MasterCard.32

MASTERCARD In the mid-1990s, Visa and American Express were battling fiercely for market leadership. To get back into the picture, MasterCard, with its ad agency McCann Erickson, launched the now iconic “Priceless” ad campaign in 1997 to strengthen its brand image. Each ad focused on a consumer activity (such as a father and son going to a baseball game) and identified three tangible products or services purchased as part of that activity and their prices (“One autographed baseball. $50”) before ending with the true but intangible payoff (“Real conversation with 11-year-old son. Priceless.”). The ads always ended with the campaign tagline, “There are some things money can’t buy; for everything else, there’s MasterCard.” The campaign stressed the duality of the MasterCard brand, communicating both its rational advantages—acceptance at establishments worldwide—and the emotional payoffs those advantages permitted. The campaign has been a global success for more than 17 years, running similarly structured ads in 102 markets and 50 languages. Lately, it has emphasized enabling “priceless” moments with the “Priceless Cities” initiative, launched in 2011 to create special events for MasterCard cardholders in major cities around the world.

Creating significant brand equity requires reaching the top of the brand pyramid, which occurs only if the right building blocks are put into place.

- Brand salience is how often and how easily customers think of the brand under various purchase or consumption situations—the depth and breadth of brand awareness.

- Brand performance is how well the product or service meets customers’ functional needs.

- Brand imagery describes the extrinsic properties of the product or service, including the ways in which the brand attempts to meet customers’ psychological or social needs.

- Brand judgments focus on customers’ own personal opinions and evaluations.

- Brand feelings are customers’ emotional responses and reactions with respect to the brand.

- Brand resonance describes the relationship customers have with the brand and the extent to which they feel they’re “in sync” with it.

Resonance is the intensity of customers’ psychological bond with the brand and the level of activity it engenders.33 Brands with high resonance include Harley-Davidson, Apple, and eBay. Fox News has found that the higher levels of resonance and engagement its programs engender often lead to greater recall of the ads it runs.34

2. MARKETING INSIGHT Brand Bubble Trouble

In The Brand Bubble, brand consultants Ed Lebar and John Gerzema use Y&R’s historical BAV database to conduct a comprehensive examination of the state of brands. Beginning with data from mid-2004, they discovered several odd trends. For thousands of consumer goods and services brands, key brand value measures such as consumer “top-of-mind” awareness, trust, regard, and admiration experienced significant drops.

At the same time, however, share prices for a number of years were being driven higher by the intangible value the markets were attributing to consumer brands. Digging deeper, Lebar and Gerzema found the increase was actually due to a very few extremely strong brands such as Google, Apple, and Nike. The value created by the vast majority of brands was stagnating or falling.

The authors viewed this mismatch between the value consumers see in brands and the value the markets were ascribing to them as a recipe for disaster in two ways. At the macroeconomic level, it implied that stock prices of most consumer companies were overstated. At the microeconomic, company level, it pointed to a serious and continuing problem in brand management.

Why have consumer attitudes toward brands declined? The research identified three fundamental causes. First, there has been a proliferation of brands. New product introductions have accelerated, but many fail to register with consumers. Two, consumers expect creative “big ideas” from brands and feel they are just not getting them. Finally, due to corporate scandals, product crises, and executive misbehavior, trust in brands has declined.

Yet vital brands are still being successfully built. Although all four pillars of the BAV model play a role, the strongest brands resonated with consumers in a special way. Amazon.com, Axe, Facebook, Innocent, IKEA, Land Rover, LG, LEGO, Tata, Nano, Twitter, Whole Foods, and Zappos exhibited notable energized differentiation by communicating dynamism and creativity in ways most other brands did not.

Formally, the BAV analysis identified three factors that help define energy and the marketplace momentum it creates:

- Vision—A clear direction and point of view on the world and how it can and should be changed.

- Invention—An intention for the product or service to change the way people think, feel, and behave.

- Dynamism—Excitement and affinity in the way the brand is presented.

John Gerzema’s follow-up research with Michael D’Antonio, published in Spend Shift, examined developments later in the decade and the way consumers were changing—or not—as a result of the traumatic economic recession. The authors describe “Spend Shift” as “a consumer-led movement to express their values through the power of their spending. We’re moving from mindless to mindful consumption. People are returning to old-fashioned virtues, such as self-reliance, thrift, faith, creativity, hard work and community—and powering them with social behaviors and technology.”

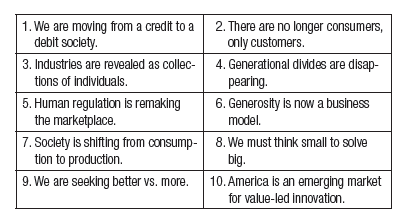

The authors make several telling observations: Trust is declining across industries, and brand attribute characteristics such as “kind,” “empathetic,” “socially responsible,” and “leader” are rising in importance with consumers. The authors offer 10 “postconsumer learnings”:

Source: Kotler Philip T., Keller Kevin Lane (2015), Marketing Management, Pearson; 15th Edition.

Howdy very nice web site!! Man .. Beautiful .. Superb .. I’ll bookmark your web site and take the feeds additionallyKI am satisfied to find a lot of helpful information right here in the post, we want develop extra techniques on this regard, thanks for sharing. . . . . .