A company’s positioning and differentiation strategy must change as its product, market, and competitors change over the product life cycle (PLC). To say a product has a life cycle is to assert four things:

- Products have a limited life.

- Product sales pass through distinct stages, each posing different challenges, opportunities, and problems to the seller.

- Profits rise and fall at different stages of the product life cycle.

- Products require different marketing, financial, manufacturing, purchasing, and human resource strategies in each life-cycle stage.

1. PRODUCT LIFE CYCLES

Most product life cycles are portrayed as bell-shaped curves, typically divided into four stages: introduction, growth, maturity, and decline55 (see Figure 12.5).

- Introduction—A period of slow sales growth as the product is introduced in the market. Profits are nonexistent because of the heavy expenses of product introduction.

- Growth—A period of rapid market acceptance and substantial profit improvement.

- Maturity—A slowdown in sales growth because the product has achieved acceptance by most potential buyers. Profits stabilize or decline because of increased competition.

- Decline—Sales show a downward drift and profits erode.

We can use the PLC concept to analyze a product category (liquor), a product form (white liquor), a product (vodka), or a brand (Absolut). Not all products exhibit a bell-shaped PLC.56 Three common alternate patterns are shown in Figure 12.6.

Figure 12.6(a) shows a growth-slump-maturity pattern, characteristic of small kitchen appliances like bread makers and toaster ovens. Sales grow rapidly when the product is first introduced and then fall to a “petrified” level sustained by late adopters buying the product for the first time and early adopters replacing it.

The cycle-recycle pattern in Figure 12.6 (b) often describes the sales of new drugs. The pharmaceutical company aggressively promotes its new drug, producing the first cycle. Later, sales start declining, and another promotion push produces a second cycle (usually of smaller magnitude and duration).57

Another common pattern is the scalloped PLC in Figure 12.6 (c). Here, sales pass through a succession of life cycles based on the discovery of new product characteristics, uses, or users. Sales of nylon showed a classic scalloped pattern because of the many new uses—parachutes, hosiery, shirts, carpeting, boat sails, automobile tires— discovered over time.5

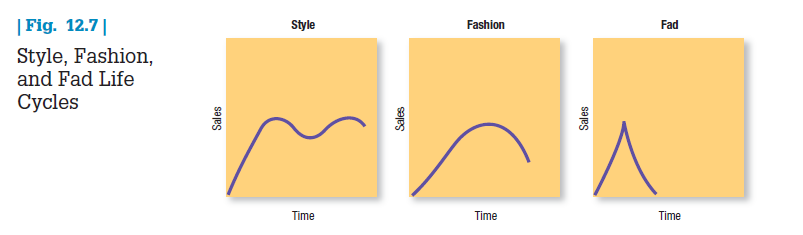

2. STYLE, FASHION, AND FAD LIFE CYCLES

We need to distinguish three special categories of product life cycles: styles, fashions, and fads (Figure 12.7). A style is a basic and distinctive mode of expression appearing in a field of human endeavor. Homes can be colonial, ranch, or Cape Cod; clothing is formal, business casual, or sporty; art is realistic, surrealistic, or abstract. A style can last for generations and go in and out of vogue. A fashion is a currently accepted or popular style in a given field. Fashions pass through four stages: distinctiveness, emulation, mass fashion, and decline.59

The length of a fashion cycle is hard to predict. One view is that fashions end because they represent a compromise, and consumers start looking for the missing attributes.60 For example, as automobiles become smaller, they become less comfortable, and then a growing number of buyers start wanting larger cars. Another explanation is that too many consumers adopt the fashion, discouraging others. Still another is that the length of a fashion cycle depends on whether the fashion meets a genuine need, is consistent with other trends, satisfies societal norms and values, and keeps within technological limits as it develops.61

Fads are fashions that come quickly into public view, are adopted with great zeal, peak early, and decline very fast. Their acceptance cycle is short, and they tend to attract only a limited following searching for excitement or wanting to distinguish themselves from others. Heelys wheeled shoes were the rage with kids—for a while. Dwindling sales resulted in a sale to a private equity company for a fraction of what the company was worth at its IPO.

Fads decline because they don’t normally satisfy a strong need. The marketing winners are those who recognize fads early and leverage them into products with staying power, as Crocs has tried to do.63

CROCS Crocs’ signature plastic clogs or “boat shoes”—colorful, comfortable, perfect for summer—succeeded soon after their introduction in Boulder, CO, in 2002. The company’s 2006 IPO was the largest ever in U.S. footwear, raising $208 million. Its stock peaked a year later when Crocs’ sales reached $847 million. But the recession and consumer fatigue with the brand were a double whammy that led to a steep drop in sales and drove the stock price down to a mere $1 in what the CFO now calls a “near-death experience.” By 2011, however, Crocs had rebounded with more than $1 billion in revenues and growth goals of 15 percent to 20 percent. What happened? The company had diversified into more than 300 styles of stylish, comfortable boots, loafers, sneakers, and other shoes that helped to reduce its reliance on clogs to less than 50 percent of sales. It also adopted a multichannel distribution approach to sell wholesale through retailers like Kohl’s and Dick’s Sporting Goods (60 percent of business), as well as directly online (10 percent) and through more than 500 of its own retail stores (30 percent). International sales now make up more than half its sales, including in emerging marketing and the growing middle-class markets in Asia and Latin America.

3.MARKETING STRATEGIES: INTRODUCTION STAGE AND THE PIONEER ADVANTAGE

Because it takes time to roll out a new product, work out technical problems, fill dealer pipelines, and gain consumer acceptance, sales growth tends to be slow in the introduction stage. Profits are negative or low, and promotional expenditures are at their highest ratio to sales because of the need to (1) inform potential consumers, (2) induce product trial, and (3) secure distribution in retail outlets.64 Prices tend to be higher because costs are high, and firms focus on buyers who are the most ready to buy. Consider the challenges Zipcar faced in trying to establish itself in the hourly car rental market.65

ZIPCAR Car sharing started in Europe as a means to serve those who frequently used public transportation but still needed a car a few times a month. In the United States, the appeal of Zipcar, the market leader and pioneer in car sharing, has been both environmental and economic. With a $50 membership fee and rates that total less than $100 a day— including gas, insurance, and parking—a typical family could save $3,000 to $4,000 a year by substituting Zipcar use for car ownership. The firm estimated that every car it added kept up to 20 private cars off the road. Targeting major cities and college campuses, offering a wide variety of vehicles, and facing little competition, it grew about 30 percent annually for a number of years. Rental leader Hertz decided to enter the hourly car rental business in 2012, however, equipping its entire 375,000-vehicle U.S. fleet with devices that let customers use a computer or smart phone to reserve and unlock a rental car. Unlike Zipcar, Hertz offers one-way rentals and charges no membership or annual fees. With Enterprise also entering the market at home, Zipcar set its sights overseas, concentrating initially on the United Kingdom and Spain. Needing resources to capitalize on global opportunities, in January 2013 it agreed to be acquired by Avis Budget, the number-two rental car company.

Companies that plan to introduce a new product must decide when to do so. To be first can be rewarding, but risky and expensive. To come in later makes sense if the firm can bring superior technology, quality, or brand strength to create a market advantage. We next consider some of the pros and cons of being a pioneer in a new market.

What are the sources of the pioneer’s advantage? “Marketing Insight: Understanding Double Jeopardy” describes one way market leaders can benefit from loyalty due to their size. Early users will recall the pioneer’s brand name if the product satisfies them. The pioneer’s brand also establishes the attributes the product class should possess.69 It normally aims at the middle of the market and so captures more users. Customer inertia also plays a role, and there are producer advantages: economies of scale, technological leadership, patents, ownership of scarce assets, and the ability to erect other barriers to entry. Pioneers can spend marketing dollars more effectively and enjoy higher rates of repeat purchases. An alert pioneer can lead indefinitely.

PIONEERING DRAWBACKS But the pioneering advantage is not inevitable.70 Bowmar (hand calculators), Apple’s Newton (personal digital assistant), Netscape (Web browser), Reynolds (ballpoint pens), and Osborne (portable computers) were market pioneers overtaken by later entrants. First movers also have to watch out for the “second-mover advantage.”

Steven Schnaars studied 28 industries in which imitators surpassed the innovators.71 He found several weaknesses among the failing pioneers, including new products that were too crude, were improperly positioned, or appeared before there was strong demand; product-development costs that exhausted the innovator’s resources; a lack of resources to compete against entering larger firms; and managerial incompetence or unhealthy complacency. Successful imitators thrived by offering lower prices, continuously improving the product, or using brute market power to overtake the pioneer.

Peter Golder and Gerald Tellis raise further doubts about the pioneer advantage.72 They distinguish between an inventor, first to develop patents in a new-product category, a product pioneer, first to develop a working model, and a market pioneer, first to sell in the new-product category. Including nonsurviving pioneers in their sample, they conclude that although pioneers may still have an advantage, more market pioneers fail than has been reported, and more early market leaders (though not pioneers) succeed. Later entrants overtaking market pioneers through the years included Matsushita over Sony in VCRs, GE over EMI in CAT scan equipment, and Google over Yahoo! in search.

Follow-up research by Golder and his colleagues of 625 brand leaders in 125 categories from 1921 to 2010 provides further insight:

- Leading brands are more likely to persist during economic slowdowns and when inflation is high and less likely to persist during economic expansion and when inflation is low.

- Half the leading brands in the sample lost their leadership after being a leader over periods ranging from 12 to 39 years.

- The rate of brand leadership persistence has been substantially lower in recent eras than in earlier eras (e.g., more than 30 years ago).

- Once brand leadership has been lost, it is rarely regained.

- Categories with above-average brand leadership persistence are food and household supplies; those with below-average rates are durables and clothing.

GAINING A PiONEERING ADVANTAGE Tellis and Golder also identified five factors underpinning long-term market leadership: vision of a mass market, persistence, relentless innovation, financial commitment, and asset leverage.74 Other research has highlighted the role of genuine product innovation.75 When a pioneer starts a market with a really new product, like the Segway Human Transporter, surviving can be very challenging. For incremental innovators, like MP3 players with video capabilities, survival rates are much higher.

Speeding up innovation is essential in an age of shortening product life cycles. Being early has been shown to pay. One study found that products debuting six months late but on budget earned an average of 33 percent less profit in their first five years; products that came out on time but 50 percent over budget sacrificed only 4 percent of potential profits.76

Companies should not try to move too fast; they must carefully design and execute their product-launch marketing. General Motors rushed out its newly designed Malibu to get a leg up over its Honda, Nissan, and Ford midsize competitors. When all the different versions were not ready for production at launch, the brand’s momentum stalled.77 One study found Internet companies that realized benefits from moving fast (1) were first movers in large markets, (2) erected barriers of entry against competitors, and (3) directly controlled critical elements necessary for starting a company.78

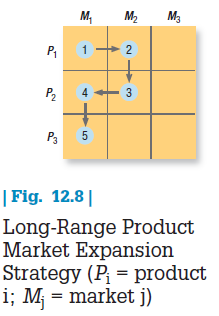

The pioneer should visualize the product markets it could enter, knowing it cannot enter all of them at once. Suppose market-segmentation analysis reveals the segments shown in Figure 12.8. The pioneer should analyze the profit potential of each singly and of all together and decide on a market expansion path. Thus, the pioneer in Figure 12.8 plans first to enter product market P1M1, then move into a second market (PjM2), then surprise the competition by developing a second product for the second market (P2M2), then take the second product back into the first market (P2M1), then launch a third product for the first market (P3M1). If this game plan works, the pioneer firm will own a good part of the first two segments, serving each with two or three products.

4. MARKETING INSIGHT Understanding Double Jeopardy

Double jeopardy is an empirical generalization that has roots in many areas but was popularized in marketing by the British academic Andrew Ehrenberg. It boils down to the fact that a small-share brand is penalized twice—it has fewer buyers than a large-share brand, and they buy less frequently. As a consequence, most of a brand’s market share is explained by its market penetration and the size of its customer base, rather than by customers’ repeat purchases.

Implicit in the principle of double jeopardy is the assumption that brands are substitutable and have target segments in common. It is, in fact, most often observed with weakly differentiated brands targeting the same group of people. Exceptions are highly differentiated niche brands that thrive on small shares and high loyalty and seasonal brands that offer unique value and tally cluster purchases in short periods of time.

One implication drawn by double jeopardy proponents is that marketers seeking growth should focus on increasing the size of the customer base rather than on deepening the loyalty of existing customers. They see PR efforts, distribution plans, and any means to increase brand exposure, familiarity, and availability as more important than persuasive advertising to target switchers or CRM efforts to reward loyal customers.

Critics of double jeopardy question how inevitable it is and see other implications for marketers. For example, they view new or established brands with a new positioning or message as differentiated enough to avoid double jeopardy’s predicted results.

5. MARKETING STRATEGIES: GROWTH STAGE

The growth stage is marked by a rapid climb in sales. Early adopters like the product, and additional consumers start buying it. New competitors enter, attracted by the opportunities. They introduce new product features and expand distribution. Prices stabilize or fall slightly, depending on how fast demand increases.

Companies maintain marketing expenditures or raise them slightly to meet competition and continue to educate the market. Sales rise much faster than marketing expenditures, causing a welcome decline in the marketing-to-sales ratio. Profits increase as marketing costs are spread over a larger volume, and unit manufacturing costs fall faster than price declines, owing to the producer-learning effect. Firms must watch for a change to a decelerating rate of growth in order to prepare new strategies.

To sustain rapid market share growth now, the firm:

- improves product quality and adds new features and improved styling.

- adds new models and flanker products (of different sizes, flavors, and so forth) to protect the main product.

- enters new market segments.

- increases its distribution coverage and enters new distribution channels.

- shifts from awareness and trial communications to preference and loyalty communications.

- lowers prices to attract the next layer of price-sensitive buyers.

By spending money on product improvement, promotion, and distribution, the firm can capture a dominant position. It trades off maximum current profit for high market share and the hope of even greater profits in the next stage.

Sustaining a competitive advantage in the face of many possible marketplace changes can be challenging but not impossible, as evidenced by some of the long-time market leaders noted above. Finding new ways to consistently improve customer satisfaction can go a long way. Brambles, a leading Australian logistics supplier, designed plastic bins for its grocery customers that could be filled in farmers’ fields and placed directly on store shelves, saving the grocers significant labor costs in the process.79

6. MARKETING STRATEGIES: MATURITY STAGE

At some point, the rate of sales growth will slow, and the product will enter a stage of relative maturity. Most products are in this stage of the life cycle, which normally lasts longer than the preceding ones.

The maturity stage divides into three phases: growth, stable, and decaying maturity. In the first, sales growth starts to slow. There are no new distribution channels to fill. New competitive forces emerge. In the second phase, sales per capita flatten because of market saturation. Most potential consumers have tried the product, and future sales depend on population growth and replacement demand. In the third phase, decaying maturity, the absolute level of sales starts to decline, and customers begin switching to other products.

This third phase poses the most challenges. The sales slowdown creates overcapacity in the industry, which intensifies competition. Weaker competitors withdraw. A few giants dominate—perhaps a quality leader, a service leader, and a cost leader—and they profit mainly through high volume and lower costs. Surrounding them is a multitude of market nichers, including market specialists, product specialists, and customizing firms.

The question is whether to struggle to become one of the big three and achieve profits through high volume and low cost or to pursue a niching strategy and profit through low volume and high margins. Sometimes the market will divide into low- and high-end segments, and market shares of firms in the middle will steadily erode. Here’s how Swedish appliance manufacturer Electrolux has coped with this situation.80

ELECTROLUX AB In 2002, Swedish manufacturer Electrolux faced a rapidly polarizing appliance market. Low-cost Asian companies such as Haier, LG, and Samsung were applying downward price pressure, while premium competitors like Bosch, Sub-Zero, and Viking were growing at the expense of the middle-of-the-road brands. Electrolux’s CEO at the time, Hans Straberg, decided to escape the middle by rethinking customers’ wants and needs. He segmented the market according to the lifestyle and purchasing patterns of about 20 different types of consumers to help target and position the company’s broad portfolio of brands, which includes Electrolux as well as Frigidaire refrigerators, AEG ovens, and Zanussi coffee machines. Electrolux now successfully markets its steam ovens to health-oriented consumers, for example, and its compact dishwashers, originally for smaller kitchens, to a broader consumer segment that washes dishes more often. To companies stuck in the middle of a mature market, Straberg offered this advice: “Start with consumers and understand what their latent needs are and what problems they experience.. .then put the puzzle together yourself to discover what people really want to have. Henry Ford is supposed to have said, ‘If I had asked people what they really wanted, I would have made faster horses’ or something like that. You need to figure out what people really want, although they can’t express it.” Under new CEO Keith McLoughlin, Electrolux is concentrating on the top end of the appliance market, selling professional-grade ranges to the ultra-luxury consumer segment. With distribution and local market presence in more than 150 countries, the company is well positioned for global growth, especially in emerging markets.

Some companies abandon weaker products to concentrate on new and more profitable ones. Yet they may be ignoring the high potential many mature markets and old products still have. Industries widely thought to be mature—autos, motorcycles, television, watches, cameras—were proved otherwise by Japanese firms, who found ways to offer customers new value. Three ways to change the course for a brand are market, product, and marketing program modifications.

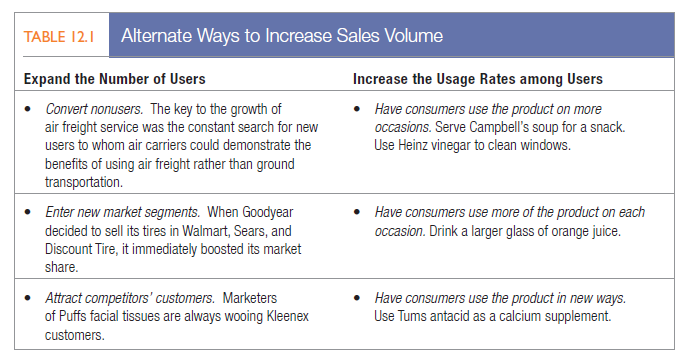

MARKET MODIFICATION A company might try to expand the market for its mature brand by working with the two factors that make up sales volume, number of brand users and usage rate per customer, as in Table 12.1, but competitors may match this strategy.

PRODUCT MODIFICATION Managers also try to stimulate sales by improving quality, features, or style. Quality improvement increases functional performance by launching a “new and improved” product. Feature improvement adds size, weight, materials, supplements, and accessories that expand the product’s performance, versatility, safety, or convenience. Style improvement increases the product’s esthetic appeal.

Any of these improvements can attract consumer attention. In the highly competitive digital photography space, Shutterfly has grown revenue to $600 million in annual sales by converting customers’ digital images to tangible items: photo books, calendars, greeting cards, wedding invitations, wall decals, and more.81

The paper industry is also coping with the challenges of the digital era. As long as some consumers prefer to read, store, or share hard-copy documents, the industry recognizes it must also provide as environmentally sound a solution as possible. Suppliers have worked to develop a more environmentally friendly supply chain from seedlings and reforestation, adopt greener pulp and paper production, recycle, and reduce their carbon footprint.82 Such efforts are crucial for success and even survival. Due to the rise of e-mail, online bill payments, and other digital developments, leading envelope maker National Envelope declared Chapter 11 bankruptcy twice from 2011 to 2013 as a result of dwindling sales, while leading postage meter supplier Pitney Bowes expanded its digital operations.83

MARKETING PROGRAM MODIFICATION Finally, brand managers might also try to stimulate sales by modifying non-product elements—price, distribution, and communications in particular—as we will review in later chapters. They should assess the likely success of any changes in terms of their effects on new and existing customers.

7. MARKETING STRATEGIES: DECLINE STAGE

Sales decline for a number of reasons, including technological advances, shifts in consumer tastes, and increased domestic and foreign competition. All can lead to overcapacity, increased price cutting, and profit erosion. The decline might be slow, as for sewing machines and newspapers, or rapid, as it was for 5.25 floppy disks and eight- track cartridges. Sales may plunge to zero or petrify at a low level. These structural changes are different from a short-term decline resulting from a marketing crisis of some sort. “Marketing Memo: Managing a Marketing Crisis” describes strategies for a brand in temporary trouble.

As sales and profits decline, some firms withdraw. Those remaining may reduce the number of products they offer, exiting smaller segments and weaker trade channels, cutting marketing budgets, and reducing prices further. Unless strong reasons for retention exist, carrying a weak product is often very costly. Encyclopedia Britannica ceased production of its iconic bound sets of encyclopedias once consumers felt they could get adequate content elsewhere for much less or free. The company rebounded by focusing on the online educational market. Valuing the company’s long-standing mission to bring expert knowledge to the general public, more than half of U.S. students and teachers have access to some Britannica content.84

ELIMINATING WEAK PRODUCTS Besides being unprofitable, weak products consume a disproportionate amount of management’s time, require frequent price and inventory adjustments, incur expensive setup for what are usually short production runs, draw advertising and sales force attention better used to make healthy products more profitable, and cast a negative shadow on company image. Maintaining them also delays the aggressive search for replacement products, creating a lopsided product mix long on yesterday’s breadwinners and short on tomorrow’s.

Recognizing these drawbacks, General Motors decided to drop the floundering Oldsmobile and Pontiac lines.85 Unfortunately, most companies have not developed a policy for handling aging products. The first task is to establish a system for identifying them. Many companies appoint a product-review committee with representatives from marketing, R&D, manufacturing, and finance who, based on all available information, make a recommendation for each product—leave it alone, modify its marketing strategy, or drop it.86

Some firms abandon declining markets earlier than others. Much depends on the height of exit barriers in the industry. The lower the barriers, the easier for firms to leave the industry, and the more tempting for the remaining firms to stay and attract the withdrawing firms’ customers. Procter & Gamble stayed in the declining liquid-soap business and improved its profits as others withdrew.

The appropriate strategy also depends on the industry’s relative attractiveness and the company’s competitive strength in it. A company in an unattractive industry that possesses competitive strength should consider shrinking selectively. A company in an attractive industry that has competitive strength should consider strengthening its investment. Companies that successfully restage or rejuvenate a mature product often do so by adding value to it.

HARVESTING AND DIVESTING Strategies for harvesting and for divesting are quite different. Harvesting calls for gradually reducing a product or business’s costs while trying to maintain sales. The first step is to cut R&D costs and plant and equipment investment. The company might also reduce product quality, sales force size, marginal services, and advertising expenditures, ideally without letting customers, competitors, and employees know what is happening. Harvesting is difficult to execute, yet many mature products warrant this strategy. And it can substantially increase current cash flow.87

When a company decides to divest a product with strong distribution and residual goodwill, it can probably sell it to another firm. Some firms specialize in acquiring and revitalizing “orphan” or “ghost” brands that larger firms want to divest or that have encountered bankruptcy, such as Linens n’ Things, Folgers and Brim coffee, Nuprin pain reliever, and Salon Selective shampoos.88 These firms attempt to capitalize on the residue of awareness in the market to develop a brand revitalization strategy. Reserve Brands bought Eagle Snacks in part because research showed 6 of 10 adults remembered the brand, leading Reserve’s CEO to observe, “It would take $300 million to $500 million to recreate that brand awareness today.”89

If the company can’t find any buyers, it must decide whether to liquidate the brand quickly or slowly. It must also decide how much inventory and service to maintain for past customers.

8. MARKETING MEMO Managing a Marketing Crisis

Marketing managers must assume a brand crisis will someday arise. Chick-fil-A, BP, Domino’s, and Toyota have all experienced damaging and even potentially crippling brand crises. Bank of America, JPMorgan, AIG, and other financial services firms have been rocked by scandals that significantly eroded investor trust. Repercussions include (1) lost sales, (2) reduced effectiveness of marketing activities, (3) increased sensitivity to rivals’ marketing activities, and (4) reduced impact of the firm’s marketing activities on competing brands.

In general, the stronger the brand equity and corporate image—especially credibility and trustworthiness—the more likely the firm can weather the storm. Careful preparation and a well-managed crisis management program are also critical, however. As Johnson & Johnson’s legendary and nearly flawless handling of the Tylenol product-tampering incident taught marketers everywhere, consumers must see the firm’s response as both swift and sincere. They must feel an immediate sense that the company truly cares. Listening is not enough.

The longer the firm takes to respond, the more likely consumers can form negative impressions from unfavorable media coverage or word of mouth. Perhaps worse, they may find they don’t like the brand after all and permanently switch. Getting in front of a problem with PR, and perhaps even ads, can help avoid those problems.

A classic example is Perrier—the one-time brand leader in the bottled water category. In 1994, Perrier was forced to halt production worldwide and recall all existing product when traces of benzene, a known carcinogen, were found in excessive quantities in its bottled water. Over the next weeks it offered several explanations, creating confusion and skepticism. Perhaps more damaging, the product was off shelves for more than three months.

Despite an expensive relaunch featuring ads and promotions, the brand struggled to regain lost market share, and a full year later sales were less than half what they had been. With its key “purity” association tarnished, Perrier had no other compelling points-of-difference. Consumers and retailers had found satisfactory substitutes, and the brand never recovered. Eventually it was taken over by Nestle SA.

The more sincere the firm’s response—ideally a public acknowledgment of the impact on consumers and willingness to take necessary steps—the less likely consumers will form negative attributions. When shards of glass were found in some jars of its baby food, Gerber tried to reassure the public there were no problems in its manufacturing plants but adamantly refused to withdraw products from stores. After market share slumped from 66 percent to 52 percent within a couple of months, one company official admitted, “Not pulling our baby food off the shelf gave the appearance that we aren’t a caring company.”

If a problem exists, consumers need to know without a shadow of a doubt that the company has found the proper solution. One of the keys to Tylenol’s recovery was J&J’s introduction of triple tamper-proof packaging, successfully eliminating consumer worry that the product could ever be tampered with again.

Sources: Norman Klein and Stephen A. Greyser, “The Perrier Recall: A Source of Trouble,” Harvard Business School Case #9-590-104 and “The Perrier Relaunch,” Harvard Business School Case #9-590-130; Harald Van Heerde, Kristiaan Helsen, and Marnik G. Dekimpe, “The Impact of a Product-Harm Crisis on Marketing Effectiveness,” Marketing Science 26 (March—April 2007), pp. 230-45; Michelle L. Roehm and Alice M. Tybout, “When Will a Brand Scandal Spill Over and How Should Competitors Respond?” Journal of Marketing Research 43 (August 2006), pp. 366-73; Michelle L. Roehm and Michael K. Brady, “Consumer Responses to Performance Failures by High Equity Brands,” Journal of Consumer Research 34 (December 2007), pp. 537-45; Alice M. Tybout and Michelle Roehm, “Let the Response Fit the Scandal,” Harvard Business Review, December 2009, pp. 82-88; Andrew Pierce, “Managing Reputation to Rebuild Battered Brands, Marketing News, March 15, 2009, p. 19; Kevin O’Donnell, “In a Crisis Actions Matter,” Marketing News, April 15, 2009, p. 22; Anne Marie Kelly, “Has Toyota’s Image Recovered from the Brand’s Recall Crisis?,” Forbes, March 5, 2012; Mark Guarino, “Chick-fil-A: Will the Controversy Hurt Chain’s Expansion Plans?,” Christian Science Monitor, August 3, 2012; Mark McNeilly, “5 Steps to Handling Your Next Brand Crisis,” Fast Company, August 15, 2012; Kathleen Cleeren, Harald J. van Heerde, and Marnik G. Dekimpe, “Rising from the Ashes: How Brands and Categories Can Overcome Product-Harm Crises,” Journal of Marketing 77 (March 2013), pp. 58-77.

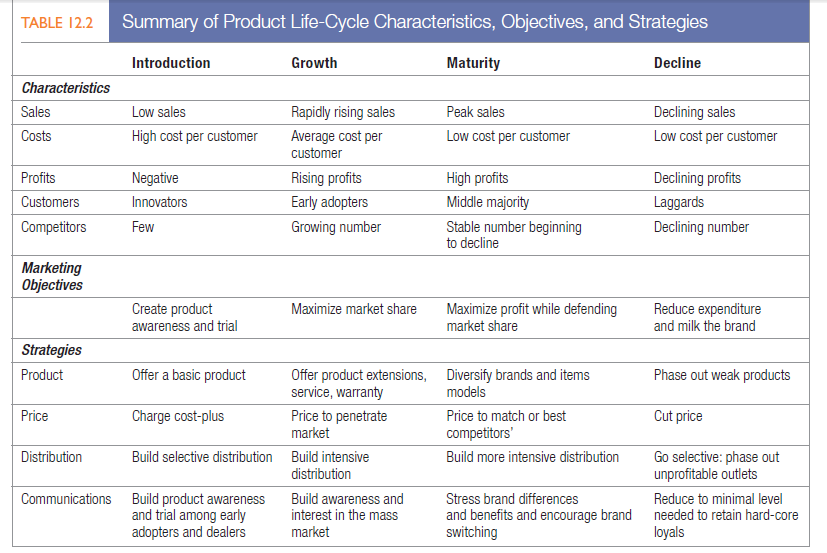

9. EVIDENCE FOR THE PRODUCT LIFE-CYCLE CONCEPT

Table 12.2 summarizes the characteristics, marketing objectives, and marketing strategies of the four stages of the product life cycle. The PLC concept helps marketers interpret product and market dynamics, conduct planning and control, and do forecasting. Another study by Golder and Tellis of 30 product categories unearthed a number of interesting findings about the PLC:90

- New consumer durables show a distinct takeoff, after which sales increase by roughly 45 percent a year, but they also show a distinct slowdown, when sales decline by roughly 15 percent a year.

- Slowdown occurs at 34 percent penetration on average, well before most households own a new product.

- The growth stage lasts a little more than eight years and does not seem to shorten over time.

- Informational cascades exist, meaning people are more likely to adopt over time if others already have, instead of making careful product evaluations. One implication is that product categories with large sales increases at takeoff tend to have larger sales declines at slowdown.

10. CRITIQUE OF THE PRODUCT LIFE-CYCLE CONCEPT

PLC theory has its share of critics, who claim life-cycle patterns are too variable in shape and duration to be generalized and that marketers can seldom tell what stage their product is in. A product may appear mature when it has actually reached a plateau prior to another upsurge. Critics also charge that, rather than an inevitable course, the PLC pattern is the self-fulfilling result of marketing strategies and that skillful marketing can in fact lead to continued growth.91

11. MARKET EVOLUTION

Because the PLC focuses on what’s happening to a particular product or brand rather than the overall market, it yields a product-oriented rather than a market-oriented picture. Firms also need to visualize a market’s evolutionary path as it is affected by new needs, competitors, technology, channels, and other developments and change product and brand positioning to keep pace.92 Like products, markets evolve through four stages: emergence, growth, maturity, and decline. Consider the evolution of the paper towel market.

PAPER TOWELS Homemakers originally used cotton and linen dishcloths and towels in their kitchens. Then a paper company looking for new markets developed paper towels, crystallizing a latent market that other manufacturers entered. The number of brands grew and created market fragmentation. Industry overcapacity led manufacturers to search for new features. One manufacturer, hearing consumers complain that paper towels were not absorbent, introduced “absorbent” towels and increased its market share. Competitors produced their own versions of absorbent paper towels, and the market fragmented again. One manufacturer introduced a “superstrength” towel that was soon copied. Another introduced a “lint-free” towel, subsequently copied. A later innovation was wipes containing a cleaning agent (like Clorox Disinfecting Wipes) that are often surface-specific (for wood, metal, or stone). Thus, driven by innovation and competition, paper towels evolved from a single product to one with various absorbencies, strengths, and applications.

Source: Kotler Philip T., Keller Kevin Lane (2015), Marketing Management, Pearson; 15th Edition.

Great line up. We will be linking to this great article on our site. Keep up the good writing.