A firm’s branding strategy—often called its brand architecture—reflects the number and nature of both common and distinctive brand elements. Deciding how to brand new products is especially critical. A firm has three main choices:

- It can develop new brand elements for the new product.

- It can apply some of its existing brand elements.

- It can use a combination of new and existing brand elements.

When a firm uses an established brand to introduce a new product, the product is called a brand extension. When marketers combine a new brand with an existing brand, the brand extension can also be called a subbrand, such as Hershey Kisses candy, Adobe Acrobat software, Toyota Camry automobiles, and American Express Blue cards. The existing brand that gives birth to a brand extension or sub-brand is the parent brand. If the parent brand is already associated with multiple products through brand extensions, it can also be called a master brand or family brand.

Brand extensions fall into two general categories. In a line extension, the parent brand covers a new product within a product category it currently serves, such as with new flavors, forms, colors, ingredients, and package sizes. Dannon has introduced several types of Dannon yogurt line extensions through the years—Fruit on the Bottom, All Natural Flavors, Dan-o-nino, and Light & Fit. In a category extension, marketers use the parent brand to enter a different product category, such as Swiss Army watches. Honda has used its company name to cover such different products as automobiles, motorcycles, snowblowers, lawn mowers, marine engines, and snowmobiles. This allows the firm to advertise that it can fit “six Hondas in a two-car garage.”

A brand line consists of all products—original as well as line and category extensions—sold under a particular brand. A brand mix (or brand assortment) is the set of all brand lines that a particular seller makes. Many companies are introducing branded variants, which are specific brand lines supplied to specific retailers or distribution channels. They result from the pressure retailers put on manufacturers to provide distinctive offerings. A camera company may supply its low-end cameras to mass merchandisers while limiting its higher-priced items to specialty camera shops. Valentino may design and supply different lines of suits and jackets to different department stores.74

A licensed product is one whose brand name has been licensed to other manufacturers that actually make the product. Corporations have seized on licensing to push their company names and images across a wide range of products—from bedding to shoes—making licensing a multibillion-dollar business. It is perhaps not surprising that in a high-involvement category such as automobiles, licensing is big business.75

AUTOMOTIVE LICENSING Several automotive brands have created lucrative licensing businesses. Jeep’s licensing program, with 600 products and 150 licensees, includes everything from strollers built for a father’s longer arms to apparel with Teflon in the denim—as long as the product fits the brand’s positioning of “Life without Limits.” Thanks to 600-plus dedicated shop-in-shops and 80 freestanding stores around the world, Jeep’s licensing revenue now exceeds $550 million in retail sales. New areas of emphasis include outdoor and travel gear, juvenile products, and sporting goods. As of 2014, Ford was generating $2 billion in licensing revenue from 18,000 different items sold through 400 licensees. Products range from apparel branded with the Ford Blue Oval logo and the popular Mustang nameplate logo to radio-controlled cars sold in major retailers like Walmart and Toys R Us. An area of growth is products designed to equip male fans and their “man caves.”

1. BRANDING DECISIONS

ALTERNATIVE BRANDING STRATEGIES Today, branding is such a strong force that hardly anything goes unbranded. Assuming a firm decides to brand its products or services, it must choose which brand names to use. Three general strategies are popular:

- Individual or separate family brand names. Consumer packaged-goods companies have a long tradition of branding different products by different names. General Mills largely uses individual brand names, such as Bisquick, Gold Medal flour, Nature Valley granola bars, Old El Paso Mexican foods, Progresso soup, Wheaties cereal, and Yoplait yogurt. If a company produces quite different products, one blanket name is often not desirable. Swift & Company developed separate family names for its hams (Premium) and fertilizers (Vigoro). Companies often use different brand names for different quality lines within the same product class. A major advantage of separate family brand names is that if a product fails or appears to be of low quality, the company has not tied its reputation to it.76

- Corporate umbrella or company brand name. Many firms, such as Heinz and GE, use their corporate brand as an umbrella brand across their entire range of products.77 Development costs are lower with umbrella names because there’s no need to research a name or spend heavily on advertising to create recognition. Campbell Soup introduces new soups under its brand name with extreme simplicity and achieves instant recognition. Sales of the new product are likely to be strong if the manufacturer’s name is good. Corporate-image associations of innovativeness, expertise, and trustworthiness have been shown to directly influence consumer evaluations.78 Finally, a corporate branding strategy can lead to greater intangible value for the firm.79

- Sub-brand name. Sub-brands combine two or more of the corporate brand, family brand, or individual product brand names. Kellogg employs a sub-brand or hybrid branding strategy by combining the corporate brand with individual product brands as with Kellogg’s Rice Krispies, Kellogg’s Raisin Bran, and Kellogg’s Corn Flakes. Many durable-goods makers such as Honda, Sony, and Hewlett-Packard use sub-brands for their products. The corporate or company name legitimizes, and the individual name individualizes, the new product.

HOUSE OF BRANDS VERSUS A BRANDED HOUSE The use of individual or separate family brand names has been referred to as a “house of brands” strategy, whereas the use of an umbrella corporate or company brand name is a “branded house” strategy. These two strategies represent two ends of a continuum. A sub-brand strategy falls somewhere between, depending on which component of the sub-brand receives more emphasis. A good example of a house of brands strategy is United Technologies.80

UNITED TECHNOLOGIES United Technology Corporation (UTC) provides a broad range of high-technology products and services for the aerospace and commercial building industries, generating nearly $63 billion in revenues. Its aerospace businesses include Sikorsky helicopters, Pratt & Whitney aircraft engines, and UTC Aerospace Systems (which includes Goodrich Corporation and Hamilton Sundstrand aerospace systems). UTC Building & Industrial Systems, the world’s largest provider of building technologies, includes Otis elevators and escalators; Carrier heating, airconditioning, and refrigeration systems; and fire and security solutions from brands such as Kidde and Chubb. Most of its in-market brands are the names of the individuals who invented the product or created the company decades ago; they have more power and are more recognizable in the business buying marketplace than the name of the parent brand, and employees are loyal to the individual companies. The UTC name is advertised only to small but influential audiences—the financial community and opinion leaders in New York and Washington, DC. “My philosophy has always been to use the power of the trademarks of the subsidiaries to improve the recognition and brand acceptance, awareness, and respect for the parent company itself,” said UTC’s one-time CEO George David.

With a branded house strategy, it is often useful to have a well-defined flagship product. A flagship product is one that best represents or embodies the brand as a whole to consumers. It often is the first product by which the brand gained fame, a widely accepted best-seller, or a highly admired or award-winning product.81

Flagship products play a key role in the brand portfolio in that marketing them can have short-term benefits (increased sales) as well as long-term benefits (improved brand equity for a range of products). Certain models play important flagship roles for many car manufacturers. Besides generating the most sales, family sedans Toyota Camry and Honda Accord represent brand values that all cars from those manufacturers share.82 In justifying the large investments incurred in launching its new 2014 Mercedes S-class automobiles, Daimler’s chief executive Dieter Zetsche explained, “This car is for Mercedes-Benz what the harbor is for Hamburg, the Mona Lisa for Leonardo da Vinci and ‘Satisfaction’ for the Rolling Stones: the most important symbol of the reputation of the whole.”83

Two key components of virtually any branding strategy are brand portfolios and brand extensions. (Chapter 13 discusses co-branding and ingredient branding, as well as line-stretching through vertical extensions.)

2. BRAND PORTFOLIOS

A brand can be stretched only so far, and all the segments the firm would like to target may not view the same brand equally favorably. Marketers often need multiple brands in order to pursue these multiple segments. Some other reasons for introducing multiple brands in a category include:84

- Increasing shelf presence and retailer dependence in the store

- Attracting consumers seeking variety who may otherwise have switched to another brand

- Increasing internal competition within the firm

- Yielding economies of scale in advertising, sales, merchandising, and physical distribution

The brand portfolio is the set of all brands and brand lines a particular firm offers for sale in a particular category or market segment. Building a good brand portfolio requires careful thinking and creative execution. In the hotel industry, brand portfolios are critical. Consider Starwood. 85

STARWOOD HOTELS & RESORTS One of the leading hotel and leisure companies in world, Starwood Hotels & Resorts Worldwide has more than 1,200 properties in 100 countries and 181,400 employees at its owned and managed properties. In its rebranding attempt to go “beyond beds,” Starwood has differentiated its hotels along emotional, experiential lines. Its hotel and call center operators convey different experiences at the firm’s different chains, as does the firm’s advertising. Starwood has nine distinct lifestyle brands in its portfolio. Here is how some of them are positioned:

-

- The largest brand, Sheraton is about warm, comforting, and casual. Its core value centers on “connections”—Sheraton enables you to connect to your location and to those back home.

- Four Points by Sheraton. For the self-sufficient traveler, Four Points is a select-service hotel that strives to be honest and uncomplicated. The brand is all about providing the comforts of home with little indulgences like local craft beers and free high-speed Internet access and bottled water.

- W With a brand personality defined as flirty, for the insider, and an escape, W offers guests unique locally inspired experiences with a “What’s New/What’s Next” attitude. W’s “Whatever/Whenever” service complements the sylish designs in its lobby gathering places and signature bars and restaurants.

- Westin. Westin’s emphasis on “personal, instinctive, and renewal” has led to a new sensory welcome featuring a white tea scent, signature music and lighting, and refreshing towels. Each room features Westin’s own “Heavenly” bed and bath products.

The hallmark of an optimal brand portfolio is the ability of each brand in it to maximize equity in combination with all the other brands in it. Marketers generally need to trade off market coverage with costs and profitability. If they can increase profits by dropping brands, a portfolio is too big; if they can increase profits by adding brands, it’s not big enough.

The basic principle in designing a brand portfolio is to maximize market coverage so no potential customers are being ignored, but minimize brand overlap so brands are not competing for customer approval. Each brand should be clearly differentiated and appealing to a sizable enough marketing segment to justify its marketing and production costs. Consider these two B-to-B and B-to-C examples.

- Dow Corning has adopted a dual-brand approach to sell its silicon, which is used as an ingredient by many companies. Silicon under the Dow Corning name uses a “high touch” approach where customers receive much attention and support; silicon sold under the Xiameter name uses a “no frills” approach emphasizing low prices.86

- Unilever, partnering with PepsiCo, sells four distinct brands of ready-to-drink iced tea. Brisk Iced Tea is an “on ramp” brand that is an entry point and a “flavor-forward” value brand; Lipton Iced Tea is a mainstream brand with an appealing blend of flavor and tea; Lipton Pure Leaf Iced Tea is premium and “tea-forward” for tea purists; and Tazo is a super-premium, niche brand.87

Marketers carefully monitor brand portfolios over time to identify weak brands and kill unprofitable ones.88 Brand lines with poorly differentiated brands are likely to be characterized by much cannibalization and require pruning. There are scores of cereals, beverages, and snacks and thousands of mutual funds. Students can choose among hundreds of business schools. For the seller, this spells hypercompetition. For the buyer, as Chapter 13 points out, it may mean too much choice.

Brands can also play a number of specific roles as part of a portfolio.

FLANKERS Flanker or fighter brands are positioned with respect to competitors’ brands so that more important (and more profitable) flagship brands can retain their desired positioning. Busch Bavarian is priced and marketed to protect Anheuser-Busch’s premium Budweiser.89 Marketers walk a fine line in designing fighter brands, which must be neither so attractive that they take sales away from their higher-priced comparison brands nor designed so cheaply that they reflect poorly on them.

CASH COWS Some brands may be kept around despite dwindling sales because they manage to maintain their profitability with virtually no marketing support. Companies can effectively milk these “cash cow” brands by capitalizing on their reservoir of brand equity. Gillette still sells the older Atra, Sensor, and Mach III razors because withdrawing them may not necessarily move customers to another Gillette razor brand.

LOW-END ENTRY LEVEL The role of a relatively low-priced brand in the portfolio often may be to attract customers to the brand franchise. Retailers like to feature these “traffic builders” because they are able to trade up customers to a higher-priced brand. Toyota’s Scion, with its quirky design and low prices, has a very specific target: people in their early 30s or under. Its specific marketing mission is to capture buyers who have not purchased anything from Toyota to move them into the franchise. The youngest average customers in the industry for eight years running, Scion drivers are in fact three-quarters first-time Toyota buyers90.

HIGH-END PRESTIGE The role of a relatively high-priced brand often is to add prestige and credibility to the entire portfolio. One analyst argued that the real value to Chevrolet of its high-performance Corvette sports car was “its ability to lure curious customers into showrooms and at the same time help improve the image of other Chevrolet cars. It does not mean a hell of a lot for GM profitability, but there is no question that it is a traffic builder.”91 Corvette’s technological image and prestige cast a halo over the entire Chevrolet line.

3. BRAND EXTENSIONS

Many firms have decided to leverage their most valuable asset by introducing a host of new products under their strongest brand names. Most new products are in fact brand extensions—typically 80 percent to 90 percent in any one year. Moreover, many of the most successful new products, as rated by various sources, are brand extensions. Among the most successful in supermarkets in 2012 were Dunkin’ Donuts coffee, Progresso Light soups, and Hormel Compleats microwave meals. Nevertheless, many new products are introduced each year as new brands. The year 2012 also saw the launch of Zyrtec allergy relief medicine and Ped Egg foot files.

ADVANTAGES OF BRAND EXTENSIONS Two main advantages of brand extensions are that they can facilitate new-product acceptance and provide positive feedback to the parent brand and company.

Improved Odds of New-Product Success Consumers form expectations about a new product based on what they know about the parent brand and the extent to which they feel this information is relevant. When Sony introduced a new personal computer tailored for multimedia applications, the Vaio, consumers may have felt comfortable with its anticipated performance because of their experience with and knowledge of other Sony products.

By setting up positive expectations, extensions reduce risk. It also may be easier to convince retailers to stock and promote a brand extension because of anticipated increased customer demand. An introductory campaign for an extension doesn’t need to create awareness of both the brand and the new product; it can concentrate on the new product itself.92

Extensions can thus reduce launch costs, important given that establishing a major new brand name for a consumer packaged good in the U.S. marketplace can cost more than $100 million! Extensions also can avoid the difficulty—and expense—of coming up with a new name and allow for packaging and labeling efficiencies. Similar or identical packages and labels can lower production costs for extensions and, if coordinated properly, provide more prominence in the retail store via a “billboard” effect.93 Stouffer’s offers a variety of frozen entrees with identical orange packaging that increases their visibility when they’re stocked together in the freezer. With a portfolio of brand variants within a product category, consumers who want a change can switch to a different product type without having to leave the brand family.

Positive Feedback Effects Besides facilitating acceptance of new products, brand extensions can provide feedback benefits.94 They can help to clarify the meaning of a brand and its core values or improve consumer loyalty to the company behind the extension.95 Through their brand extensions, Crayola means “colorful arts and crafts for kids,” Aunt Jemima means “breakfast foods” and Weight Watchers means “weight loss and maintenance”

Brand extensions can renew interest and liking for the brand and benefit the parent brand by expanding market coverage. AB InBev introduced its Budweiser Black Crown line extension—a beer with more alcohol and a stronger hops taste than regular Budweiser—with several purposes. The company hoped to both attract a younger audience being wooed by the explosion of craft brews and reinvigorate the core brand with its established base.96

A successful category extension may not only reinforce the parent brand and open up a new market but also facilitate even more new category extensions.97 The success of Apple’s iPod and iTunes products was that they: (1) opened up a new market, (2) helped sales of core Mac products, and (3) paved the way for the launch of the iPhone and iPad products.

DISADVANTAGES OF BRAND EXTENSIONS On the downside, line extensions may cause the brand name to be less strongly identified with any one product. Al Ries and Jack Trout call this the “line-extension trap.”98 By linking its brand to mainstream food products such as mashed potatoes, powdered milk, soups, and beverages, Cadbury ran the risk of losing its more specific meaning as a chocolate and candy brand.99

Brand dilution occurs when consumers no longer associate a brand with a specific or highly similar set of products and start thinking less of the brand. Porsche found sales success with its Cayenne sport-utility vehicle and Panamera four-door sedan, which accounted for three-quarters of its vehicle sales in 2012, but some critics felt the company was watering down its sports car image in the process. Perhaps in response, Porsche has dialed up its on- and off-road test tracks, driving courses, and roadshow events in recent years to help customers get the adrenaline rush of driving a legendary Porsche 911 or Boxster roadster.100

If a firm launches extensions consumers deem inappropriate, they may question the integrity of the brand or become confused or even frustrated: Which version of the product is the “right one” for them? Do they know the brand as well as they thought they did? Retailers reject many new products and brands because they don’t have the shelf or display space for them. And the firm itself may become overwhelmed.

The worst possible scenario is for an extension not only to fail, but to harm the parent brand in the process. Fortunately, such events are rare. “Marketing failures,” in which too few consumers are attracted to a brand, are typically much less damaging than “product failures,” in which the brand fundamentally fails to live up to its promise. Even then, product failures dilute brand equity only when the extension is seen as very similar to the parent brand. The Audi 5000 car suffered from a tidal wave of negative publicity and word of mouth in the mid-1980s when it was alleged to have a “sudden acceleration” problem. The adverse publicity spilled over to the 4000 model. But the Quattro was relatively insulated because it was distanced from the 5000 by its more distinct branding and advertising strategy.101

Even if sales of a brand extension are high and meet targets, the revenue may be coming from consumers switching to the extension from existing parent-brand offerings—in effect cannibalizing the parent brand. Intrabrand shifts in sales may not necessarily be undesirable if they’re a form of preemptive cannibalization. In other words, consumers who switched to a line extension might otherwise have switched to a competing brand instead. Tide laundry detergent maintains the same market share it had 50 years ago because of the sales contributions of its various line extensions—scented and unscented powder, tablet, liquid, and other forms.

One easily overlooked disadvantage of brand extensions is that the firm forgoes the chance to create a new brand with its own unique image and equity. Consider the long-term financial advantages to Disney of having introduced more grown-up Touchstone films, to Levi’s of creating casual Dockers pants, and to Black & Decker of introducing high-end DeWALT power tools.

SUCCESS CHARACTERISTICS Marketers must judge each potential brand extension by how effectively it leverages existing brand equity from the parent brand as well as how effectively, in turn, it contributes to the parent brand’s equity. Crest Whitestrips leveraged the strong reputation of Crest and dental care to provide reassurance in the teeth-whitening arena while also reinforcing its dental authority image.

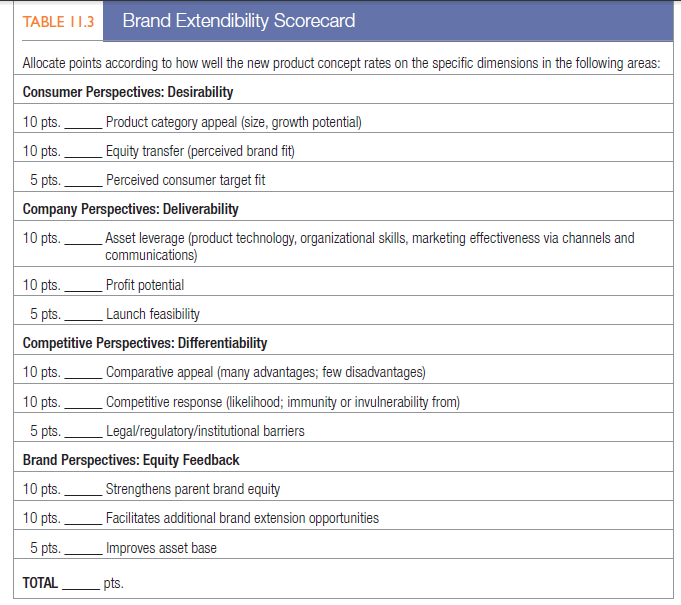

Marketers should ask a number of questions in judging the potential success of an extension.102 [1]

- Does the parent brand have strong equity?

- Is there a strong basis of fit?

- Will the extension have the optimal points-of-parity and points-of-difference?

- How can marketing programs enhance extension equity?

- What implications will the extension have for parent brand equity and profitability?

- How should feedback effects best be managed?

To help answer these questions, Table 11.3 offers a sample scorecard with specific weights and dimensions that users can adjust for each application.

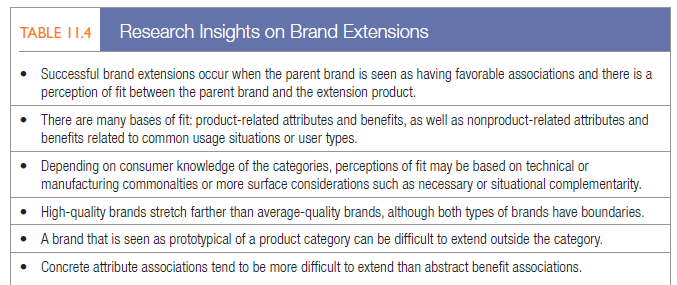

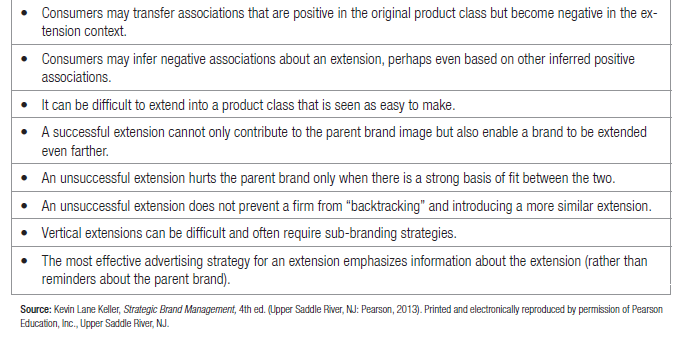

Table 11.4 lists a number of academic research findings on brand extensions.103 One major mistake in evaluating extension opportunities is failing to take all consumers’ brand knowledge structures into account and focusing instead on one or a few brand associations as a potential basis of fit.104 Bic is a classic example of that mistake.

BIC The French company Societe Bic, by emphasizing inexpensive, disposable products, was able to create markets for nonrefillable ballpoint pens in the late 1950s, disposable cigarette lighters in the early 1970s, and disposable razors in the early 1980s. It unsuccessfully tried the same strategy in marketing BIC perfumes in the United States and Europe in 1989. The perfumes—two for women (“Nuit” and “Jour”) and two for men (“BIC for Men” and “BIC Sport for Men”)—were packaged in quarter-ounce glass spray bottles that looked like fat cigarette lighters and sold for $5 each. The products were displayed on racks at checkout counters throughout Bic’s extensive distribution channels. At the time, a Bic spokeswoman described the new products as extensions of the Bic heritage—“high quality at affordable prices, convenient to purchase, and convenient to use.” The brand extension was launched with a $20 million advertising and promotion campaign containing images of stylish people enjoying themselves with the perfume and using the tagline “Paris in Your Pocket.” Nevertheless, Bic was unable to overcome its lack of cachet and negative image associations, and the extension was a failure.

Source: Kotler Philip T., Keller Kevin Lane (2015), Marketing Management, Pearson; 15th Edition.

These kind of post are always inspiring and I prefer to check out quality content so I happy to stumble on many first-rate point here in the post, writing is simply huge, thank you for the post

I conceive you have remarked some very interesting details, regards for the post.