Marketing communication activities in every medium contribute to brand equity and drive sales in many ways: by creating brand awareness, forging brand image in consumers’ memories, eliciting positive brand judgments or feelings, and strengthening consumer loyalty. The way brand associations are formed does not matter. Whether a consumer has a strong, favorable, and unique brand association of Subaru with “outdoors” “active” and “rugged” because of a TV ad that shows the car driving over rough terrain or because Subaru sponsors ski, kayak, and mountain bike events, the impact in terms of Subaru’s brand equity should be identical.

But marketing communications activities must be integrated to deliver a consistent message and achieve the strategic positioning. The starting point in planning them is a communication audit that profiles all interactions customers in the target market may have with the company and all its products and services. For example, someone interested in purchasing a new smart phone might talk to friends and family members, see television ads, read articles, look for information online, and look at smart phones in a store.

To implement the right communications programs and allocate dollars efficiently, marketers need to assess which experiences and impressions will have the most influence at each stage of the buying process. Armed with these insights, they can judge marketing communications according to their ability to affect experiences and impressions, build customer loyalty and brand equity, and drive sales. For example, how well does a proposed ad campaign contribute to awareness or to creating, maintaining, or strengthening brand associations? Does a sponsorship improve consumers’ brand judgments and feelings? Does a promotion encourage consumers to buy more of a product? At what price premium?

In building brand equity, marketers should be “media neutral” and evaluate all communication options on effectiveness (how well does it work?) and efficiency (how much does it cost?). Chrysler’s gamble with an unconventional campaign for Dodge Durango is one marketing communication program that appeared to pay off.9

DODGE DURANGO To promote its 2013 Dodge Durango, Chrysler chose actor Will Ferrell in character as Ron Burgundy to create an ad coinciding with the release of Ferrell’s Anchorman sequel. Paramount Productions, Wieden + Kennedy ad agency, and Funny or Die’s Web site production company collaborated to shoot dozens of commercials for TV and short films for the Internet of the classy but clueless 1970s-era anchorman admiring the modern features of the new Durango. In one spot, Burgundy touts the glove box as being “comfortable enough to hold two turkey sandwiches or 70 packs of gum.” A tongue-in-cheek “Hands on Ron Burgundy” online promotion rewarded those consumers who could “touch” Ron Burgundy by following a moving circle with their cursor or smart-phone button. After the campaign was launched, Web traffic shot up 80 percent with each video earning millions of views. Purchase intent rose 100 percent, and sales increased by almost 60 percent.

1. THE COMMUNICATIONS PROCESS MODELS

Marketers should understand the fundamental elements of effective communications. Two models are useful: a macromodel and a micromodel.

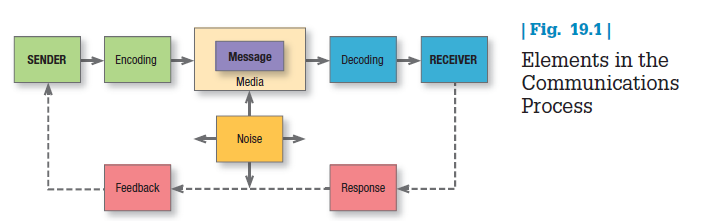

MACROMODEL OF THE COMMUNICATIONS PROCESS Figure 19.1 shows a macromodel with nine key factors in effective communication. Two represent the major parties—sender and receiver. Two represent the major tools—message and media. Four represent major communication functions—encoding, decoding, response, and feedback. The last element in the system is noise, random and competing messages that may interfere with the intended communication.

Senders must know what audiences they want to reach and what responses they want to get. They must encode their messages so the target audience can successfully decode them. They must transmit the message through media that reach the target audience and develop feedback channels to monitor the responses. The more the sender’s field of experience overlaps that of the receiver, the more effective the message is likely to be. Note that selective attention, distortion, and retention processes—first introduced in Chapter 6—may be operating.

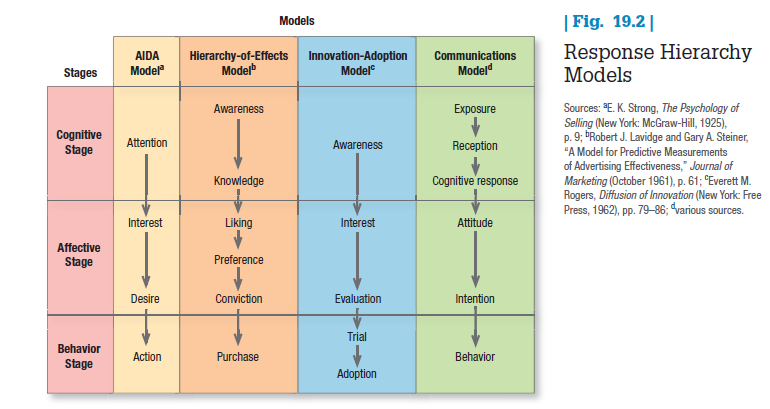

MICROMODEL OF CONSUMER RESPONSES Micromodels of marketing communications concentrate on consumers’ specific responses to communications.10 Figure 19.2 summarizes four classic response hierarchy models.

All these models assume the buyer passes through cognitive, affective, and behavioral stages in that order. This “learn-feel-do” sequence is appropriate when the audience has high involvement with a product category perceived to have high differentiation, such as an automobile or house. An alternative sequence, “do-feel-learn,” is relevant when the audience has high involvement but perceives little or no differentiation within the product category, such as airline tickets or personal computers. A third sequence, “learn-do-feel,” is relevant when the audience has low involvement and perceives little differentiation, such as with salt or batteries. By choosing the right sequence, the marketer can do a better job of planning communications.

Let’s assume the buyer has high involvement with the product category and perceives high differentiation within it. We will illustrate the hierarchy-of-effects model (the second column of Figure 19.2) in the context of a marketing communications campaign for a small Iowa college named Pottsville:

- Awareness. If most of the target audience is unaware of the object, the communicator’s task is to build awareness. Suppose Pottsville seeks applicants from Nebraska but has no name recognition there, though 30,000 Nebraska high school juniors and seniors could be interested in it. The college might set the objective of making 70 percent of these students aware of its name within one year.

- Knowledge. The target audience might have brand awareness but not know much more. Pottsville may want its target audience to know it is a private four-year college with excellent programs in English, foreign languages, and history. It needs to learn how many people in the target audience have little, some, or much knowledge about Pottsville. If knowledge is weak, Pottsville may select brand knowledge as its communications objective.

- Liking. Given target members know the brand, how do they feel about it? If the audience looks unfavorably on Pottsville College, the communicator needs to find out why. In the case of real problems, Pottsville will need to fix these and then communicate its renewed quality. Good public relations calls for “good deeds followed by good words.”

- Preference. The target audience might like the product but not prefer it to others. The communicator must then try to build consumer preference by comparing quality, value, performance, and other features to those of likely competitors.

- Conviction. A target audience might prefer a particular product but not develop a conviction about buying it. The communicator’s job is to build conviction and intent to apply among students interested in Pottsville College.

- Purchase. Finally, some members of the target audience might have conviction but not quite get around to making the purchase. The communicator must lead these consumers to take the final step, perhaps by offering the product at a low price, offering a premium, or letting them try it out. Pottsville might invite selected high school students to visit the campus and attend some classes, or it might offer partial scholarships to deserving students.

To see how fragile the communication process is, assume the probability of each of the six steps being successfully accomplished is 50 percent. The laws of probability suggest that the likelihood of all six steps occurring successfully, assuming they are independent events, is .5 x .5 x .5 x .5 x .5 x .5, which equals 1.5625 percent. If the probability of each step’s occurring were, on average, a more likely 10 percent, then the joint probability of all six events occurring drops to 0.0001 percent—or only 1 chance in 1,000,000!

To increase the odds of success for a communications campaign, marketers must attempt to increase the likelihood that each step occurs. For example, the ideal ad campaign would ensure that:

- The right consumer is exposed to the right message at the right place and at the right time.

- The ad causes the consumer to pay attention but does not distract from the intended message.

- The ad properly reflects the consumer’s level of understanding of and behaviors with the product and the brand.

- The ad correctly positions the brand in terms of desirable and deliverable points-of-difference and points-of-parity.

- The ad motivates consumers to consider purchase of the brand.

- The ad creates strong brand associations with all these stored communications effects so they can have an impact when consumers are considering making a purchase.

The challenges in achieving success with communications necessitate careful planning, a topic we turn to next.

Source: Kotler Philip T., Keller Kevin Lane (2015), Marketing Management, Pearson; 15th Edition.

you are in reality a good webmaster. The site loading speed is amazing. It seems that you are doing any distinctive trick. In addition, The contents are masterpiece. you’ve done a magnificent task on this topic!