1. DIFFERENT APPROACHES TO EQUALITY

There has been a continuing debate concerning the action that should be taken to alleviate the disadvantages that minority groups encounter. One school of thought supports legislative action, which we considered in detail in the previous chapter, and this approach is generally referred to as the equal opportunities, or liberal, approach. The other argues that this will not be effective and that the only way to change fundamentally is to alter the attitudes and preconceptions that are held about these groups. This second perspective is embodied in the managing diversity approaches. The initial emphasis on legislative action was adopted in the hope that this would eventually affect attitudes. A third, more extreme, radical approach, which enjoys less support, comes from those who advocate legislation to promote positive or reverse discrimination to compensate for a history of discrimination against specified groups and to redress the balance more immediately. In the UK, legislation provides for positive action, such as special support and encouragement, for disadvantaged groups, but not positive or reverse discrimination (discriminating in their favour). The labels ‘equal opportunities’ and ‘management of diversity’ are used inconsistently, and to complicate this there are different perspectives on the meaning of managing diversity, so we shall draw out the key differences which typify each of these approaches, and offer some critique of their conceptual foundations and efficacy.

1.1. The equal opportunities approach

The equal opportunities approach seeks to influence behaviour through legislation so that discrimination is prevented. It has been characterised by a moral and ethical stance promoting the rights of all members of society. The approach, sometimes referred to as the liberal tradition (Jewson and Mason 1986), concentrates on the equality of opportunity rather than the equality of outcome found in more radical approaches. The approach is based on the understanding that some individuals are discriminated against, for example in the selection process, due to irrelevant criteria. These irrelevant criteria arise from assumptions based on the stereotypical characteristics attributed to them as members of a socially defined group, for example that women will not be prepared to work away from home due to family commitments; that a person with a disability will have more time off sick. As these assumptions are not supported by any evidence, in respect of any individual, they are regarded as irrelevant. The equal opportunities approach therefore seeks to formalise procedures so that relevant, job-based criteria are used (using job descriptions and person specifications), rather than irrelevant assumptions. The equal opportunities legislation provides a foundation for this formalisation of procedures, and hence procedural justice. As Liff (1999) points out, the use of systematic rules in employment matters which can be monitored for compliance is ‘felt fair’. In line with the moral argument, and emphasis on systematic procedures, equal opportunities is often characterised as a responsibility of the HR department.

The rationale, therefore, is to provide a ‘level playing field’ on which all can compete on equal terms. Positive action, not positive discrimination, is allowable in order that some may reach the level at which they can compete equally. For example British Rail has given members of minority groups extra coaching and practice in a selection test for train drivers, as test taking was not part of their culture so that, when required to take a test, they were at a disadvantage.

Equal opportunities approaches stress disadvantaged groups, and the need, for example, to set targets for those groups to ensure that their representation in the workplace reflects their representation in wider society. Targets are needed in occupations where they are underrepresented, such as firefighters, police officers and in the armed forces, where small numbers of ethnic minorities are employed (see IDS 2006 for an air force example) or senior management roles where there are small numbers of women. These targets are not enforceable by legislation, as in the United States, but organisations have been encouraged to commit themselves voluntarily to improvement goals, and to support this commitment by putting in place measures to support disadvantaged groups such as special training courses and flexible employment policies.

Differences between socially defined groups should be glossed over, and the approach is generally regarded as one of ‘sameness’. That is, members of disadvantaged groups should be treated in the same way as the traditional employee (white, male, young, ablebodied and heterosexual), and not treated differently due to their group membership, unless for the purpose of providing the ‘level playing field’.

1.2. Problems with the equal opportunities approach

There is an assumption in the equal opportunities approach that equality of outcome will be achieved if fair procedures are used and monitored. In other words, if this is done it will enable any minority groups to achieve a fair share of what employment has to offer. Once such minority groups become full participating members in employment, the old stereotypical attitudes on which discrimination against particular social groups is based will gradually change, as the stereotypes will be shown to be unhelpful.

The assumption that fair procedures or procedural justice will lead to fair outcomes has not been borne out in practice, as we have shown. In addition there has been criticism of the assumption that once members of minority groups have demonstrated their ability to perform in the organisation this will change attitudes and beliefs in the organisation. This is a naive assumption, and the approach has been regarded as simplistic. Liff (1999) argues that attitudes and beliefs have been left untouched. Other criticisms point out that the legislation does not protect all minority groups (although it is gradually being extended); and there can be a general lack of support within organisations, partly because equality objectives are not linked to business objectives (Shapiro and Austin 1996). Shapiro and Austin, among others, argue that equal opportunities has often been the concern of the HR function, and Kirton and Greene (2003) argue that a weak HR function has not helped. The focus of equal opportunities is on formal processes and yet it is it not possible to formalise everything in the organisation. Recent research suggests that this approach alienated large sections of the workforce (those not identified as disadvantaged groups) who felt that there was no benefit for themselves, and indeed that their opportunities were damaged. Others felt that equal opportunities initiatives had resulted in the lowering of entry standards, as in the London Fire and Civil Defence Authority (EOR 1996). Shapiro and Austin argue that this creates divisions in the workforce. Lastly, it is the individual who is expected to adjust to the organisation, and ‘traditional equal opportunities strategies encourage a view that women (and other groups) have a problem and need help’ (Liff 1999, p. 70).

Such regulation under the Conservative government was also seen to undermine competitiveness (Dickens 2006), although more recently the Labour government has introduced some re-regulation.

In summary the equal opportunities approach is considered simplistic and to be attempting to treat the symptoms rather than the causes of unfair discrimination.

1.3. The management of diversity approach

The management of diversity approach concentrates on individuals rather than groups, and includes the improvement of opportunities for all individuals and not just those in minority groups. Hence managing diversity involves everyone and benefits everyone, which is an attractive message to employers and employees alike. Thus separate groups are not singled out for specific treatment. Kandola and Fullerton (1998, p. 4), who are generally regarded as the main UK supporters of a managing diversity approach, express it this way:

The basic concept of managing diversity accepts that the workforce consists of a diverse population of people consisting of visible and non-visible differences . . . and is founded on the premis that harnessing these differences will create a productive environment in which everyone feels valued, where all talents are fully utilized and in which organizational goals are met.

And (1998, p. 11) they contest, in addition, that:

if managing diversity is about an individual and their contribution . . . rather than about groups it is contradictory to provide training and other opportunities based solely on people’s perceived group membership.

The CIPD (2005b, p. 2) suggests the central theme of diversity as:

valuing everyone as individuals – as employees, customers, clients and extending diversity beyond what is legislated about to looking at what’s positively valued.

So the focus is on valuing difference rather than finding a way of coping fairly with it. Whereas the equal opportunities approach minimised difference, the managing diversity approach treats difference as a positive asset. Liff (1996), for example, notes that from this perspective organisations should recognise rather than dilute differences, as differences are positive rather than negative.

This brings us to a further difference between the equal opportunities approach and the managing diversity approach which is that the managing diversity approach is based on the economic and business case for recognising and valuing difference, rather than the moral case for treating people equally. Rather than being purely a cost, equal treatment offers benefits and advantages for the employer if it invests in ensuring that everyone in the organisation is valued and given the opportunities to develop his or her potential and make a maximum contribution. The practical arguments supporting the equalisation of employment opportunities are thus highlighted. CIPD (2006a) suggests that business benefits can be summed up in three broad statements: that diversity enhances customer relations and market share; that it enhances employee relations and reduces labour costs; and that it improves workforce quality and performance in terms of diverse skills, creativity, problem solving and flexibility.

For example, a company that discriminates, directly or indirectly, against older or disabled people, women, ethnic minorities or people with different sexual orientations will be curtailing the potential of available talent, and employers are not well known for their complaints about the surplus of talent. The financial benefits of retaining staff who might otherwise leave due to lack of career development or due to the desire to combine a career with family are stressed, as is the image of the organisation as a ‘good’ employer and hence its attractiveness to all members of society as its customers. A relationship between a positive diversity climate and job satisfaction and commitment to the organisation has also been found (Hicks-Clarke and Iles 2000). Although the impact on performance is more difficult to assess, it is reasonable to assume that more satisfied and committed employees will lead to reduced absence and turnover levels. In addition, the value of different employee perspectives and different types of contribution is seen as providing added value to the organisation, particularly when organisational members increasingly reflect the diverse customer base of the organisation. This provides a way in which organisations can better understand, and therefore meet, their customer needs. The business case argument is likely to have more support from managers as it is less likely to threaten the bottom line. Policies that do pose such a threat can be unpopular with managers (Humphries and Rubery 1995).

Managing diversity highlights the importance of culture. The roots of discrimination go very deep, and in relation to women Simmons (1989) talks about challenging a system of institutional discrimination and anti-female conditioning in the prevailing culture, and the Macpherson Report (1999) identifies institutional racism as a root cause of discrimination in the police force. Culture is important in two ways in managing diversity: first, organisational culture is one determinant of the way that organisations manage diversity and treat individuals from different groups. Equal opportunity approaches tended to concentrate on behaviour and, to a small extent, attitudes, whereas management of diversity approaches recognise a need to go beneath this, as the CIPD (2005b) points out that diversity requires ‘a mutual respect, obligation to and appreciation of others, irrespective of difference’ (p. 17). So changing the culture to one which treats individuals as individuals and supports them in developing their potential is critical, although the difficulties of culture change make this a very difficult task.

Second, depending on the approach to the management of diversity, the culture of different groups within the organisation comes into play. For example, recognising that men and women present different cultures at work, and that this diversity needs to be managed, is key to promoting a positive environment of equal opportunity, which goes beyond merely fulfilling the demands of the statutory codes. Masreliez-Steen (1989) explains how men and women have different perceptions, interpretations of reality, languages and ways of solving problems, which, if properly used, can be a benefit to the whole organisation, as they are complementary. She describes women as having a collectivist culture where they form groups, avoid the spotlight, see rank as unimportant and have few but close contacts. Alternatively, men are described as having an individualistic culture, where they form teams, ‘develop a profile’, enjoy competition and have many superficial contacts. The result is that men and women behave in different ways, often fail to understand each other and experience ‘culture clash’. However, the difference is about how things are done and not about what is achieved. However, we must be aware that here we have another stereotypical view which simplifies reality.

The fact that women have a different culture, with different strengths and weaknesses, means that women need managing and developing in a different way, needing different forms of support and coaching. Women more often need help to understand the value of making wider contacts and how to make them. Attending to the organisation’s culture suggests a move away from seeing the individual as the problem, and requiring that the individual needs to change because he or she does not fit the culture. Rather, it is the organisation that needs to change so that traditional assumptions of how jobs are constructed and how they should be carried out are questioned, and looked at afresh. As Liff (1999) comments, the sociology of work literature shows how structure, cultures and practices of organisations advantage those from the dominant group by adapting to their skills and lifestyles. This is the very heart of institutional discrimination, and therefore difficult to address as these are matters which are taken for granted and largely unconscious. The trick, as Thomas (1992) spells out, is to identify ‘requirements as opposed to preferences, conveniences or traditions’. This view of organisational transformation rather than individual transformation is similar to Cockburn’s (1989) ‘long agenda’ for equality, as she discusses changing cultures, systems and structures.

Finally, managing diversity is considered to be a more integrated approach to implementing equality. Whereas equal opportunities approaches were driven by the HR function, managing diversity is seen to be the responsibility of all managers. And, as there are business reasons for managing diversity it is argued that equality should not be dealt with as a separate issue, as with equal opportunities approaches, but integrated strategically into every aspect of what the organisation does; this is often called mainstreaming.

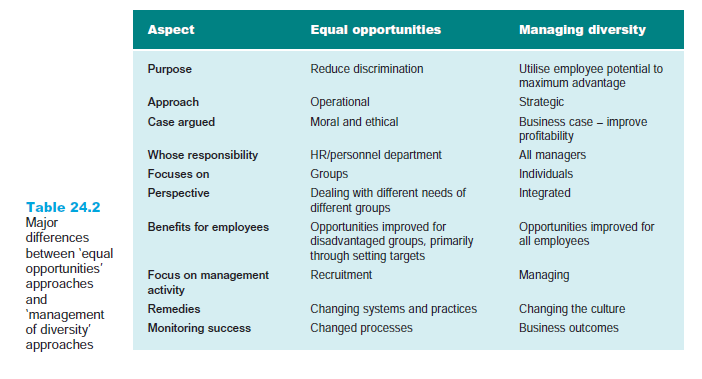

Table 24.2 summarises the key differences between equal opportunities and managing diversity.

1.4. Problems with the managing diversity approach

While the management of diversity approach was seen by many as revitalising the equal opportunities agenda, and as a strategy for making more progress on the equality front, this progress has been slow to materialise. In reality, there remains the question of the extent to which approaches have really changed in organisations. Redefining equal opportunities in the language of the enterprise culture (Miller 1996) may just be a way of making it more palatable in today’s climate, and Liff (1996) suggests that retitling may be used to revitalise the equal opportunities agenda.

It has been pointed out by Kirton and Greene (2003) that only a small number of organisations are ever quoted as management of diversity exemplars, and EOR (1999b) notes that even organisations which claim to be managing diversity do not appear to have a more diverse workforce than others, and neither have they employed more minority groups over the past five years.

Apart from this there are some fundamental problems with the management of diversity approach. The first of these is its complexity, as there are differing interpretations, which we have so far ignored, and which focus on the prominence of groups or individuals. Miller (1996) highlights two different approaches to the management of diversity. The first is where individual differences are identified and celebrated, and where prejudices are exposed and challenged via training. The second, more orthodox, approach is where the organisation seeks to develop the capacity of all. This debate between group and individual identity is a fundamental issue:

Can people’s achievements be explained by their individual talents or are they better explained as an outcome of their gender, ethnicity, class and age? Can anything meaningful be said about the collective experience of all women or are any generalisations undermined by other cross-cutting ideas? (Liff 1997, p. 11)

The most common approach to the management of diversity is based on individual contribution, as we have explained above, rather than group identity, although Liff (1997) identifies different approaches with different emphases. The individualism approach is based on dissolving differences. In other words, differences are not seen as being distributed systematically according to membership of a social group, but rather as random differences. Groups are not highlighted, but all should be treated fairly and encouraged to develop their potential. The advantage of this approach is that it is inclusive and involves all members of the organisation. An alternative emphasis in the management of diversity is that of valuing differences based on the membership of different social groups. Following this approach would mean recognising and highlighting differences, and being prepared to give special training to groups who may be disadvantaged and lack self-confidence, so that all in the organisation feel comfortable. Two further emphases are accommodating and utilising differences, which she argues are most similar to equal opportunity approaches where specific initiatives are available to aid identified groups, but also where these are also genuinely open for all other members of the organisation. In these approaches talent is recognised and used in spite of social differences, and this is done, for example, by recognising different patterns of qualifications and different roles in and out of paid work. Liff’s conclusion is that group differences cannot be ignored, because it is these very differences which hold people back.

There is a further argument that if concentration on the individual is the key feature, then this may reduce our awareness of social-group-based disadvantage (Liff 1999) and may also weaken the argument for affirmative action (Liff 1996). The attractive idea of business advantage and benefits for all may divert attention from disadvantaged groups and result in no change to the status quo (see, for example, Ouseley 1996). Young (1990) argues that if differences are not recognised, then the norms and standards of the dominant group are not questioned.

On the other hand, a management of diversity approach may reinforce group-based stereotypes, when group-based characteristics are identified and used as a source of advantage to the organisation. For example it has been argued, in respect of women, that as these differences were treated previously as a form of disadvantage, women may be uncomfortable using them to argue the basis for equality. Others argue that a greater recognition of perceived differences will continue to provide a rationale for disadvantageous treatment.

In addition to this dilemma within managing diversity approaches, the literature provides a strong criticism of the business case argument, which has been identified as contingent and variable (Dickens 1999). Thus the business case is unreliable because it will only work in certain contexts. For example, where skills are easily available there is less pressure on the organisation to promote and encourage the employment of minority groups. Not every employee interacts with customers so if image and customer contact are part of the business case this will apply only to some jobs and not to others. Also some groups may be excluded. For example, there is no systematic evidence to suggest that disabled customers are attracted by an organisation which employs disabled people. UK managers are also driven by short-term budgets and the economic benefits of equality may only be reaped in the longer term. Indeed as Kirton and Greene (2003) conclude, the business case is potentially detrimental to equality, when, for example, a cost-benefit analysis indicates that pursuing equality is not an economic benefit.

The CIPD (2006a) argues that the evidence of performance improvements resulting from diversities is scanty and identifies the need to go beyond the rhetoric of the business case for diversity and to conduct more systematic research, and monitoring to demonstrate the outcomes of diversity policies. It also points to the importance of a conducive environment in gaining benefits. Furthermore it recites problems which can result from a more diverse workforce; these include increased conflict, often resulting in difficulties in coming up with solutions, and poorer internal communication, with increased management costs due to these issues.

In terms of implementation of a diversity approach there are also difficulties. We have identified above the complexity of some of the varying ideas which come under the banner of diversity and this in itself is a barrier to implementation. Foster and Harris (2005) in their research in the retail sector found that it was a concept that lacked clarity for line managers in terms both of what it is and of how to implement it within anti-discrimination laws, and some were concerned that it may lead to feelings of unfairness and claims of unequal treatment.

There are also concerns about whether diversity management, which originated in the USA, will travel effectively to the UK where the context is different, especially in terms of the demographics and the history of equality initiatives. Furthermore, there are concerns about whether diversity can be managed at all, as Lorbiecki and Jack (2000) note:

the belief that diversity management is do-able rests on a fantasy that it is possible to imagine a clean slate on which memories of privilege and subordination leave no mark (p. 528)

and they go on to say that the theories do not take account of existing power differentials.

Lastly, managing diversity can be seen as introspective as it deals with people already in the organisation, rather than with getting people into the organisation – managing rather than expanding diversity (Donaldson 1993). Because of this Thomas (1990) suggests that it is not possible to manage diversity until you actually have it.

1.5. Equal opportunities or managing diversity?

Are equal opportunities and managing diversity completely different things? If so, is one approach preferable to the other? For the sake of clarity, earlier in this chapter we characterised a distinct approach to managing diversity which suggests that it is different from equal opportunities. Miller (1996) identifies a parallel move from the collective to the individual in the changing emphasis in personnel management as opposed to HRM.

However, as we have seen, managing diversity covers a range of approaches and emphases, some closer to equal opportunities, some very different.

Much of the management of diversity approach suggests that it is superior to and not compatible with the equal opportunities approach (see Kandola et al. 1996). There is, however, increasing support for equal opportunities and managing diversity to be viewed as mutually supportive and for this combination to be seen as important. Dickens (2006) suggests that social justice and economic efficiency are increasingly being presented as complementary, although there is so far a lack of guidance as to how this can be done in practice. To see equal opportunities and management of diversity as alternatives threatens to sever the link between organisational strategy and the realities of internal and external labour market disadvantage.

While recognising that legislation on its own cannot change attitudes, Dickens (2006) suggests that this is an important intervention, not only symbolically, but also as the market tends to produce discrimination rather than equality. In a similar vein Woodhams and Lupton (2006) underline the value of legislation in setting minimum standards.

2. IMPLICATIONS FOR ORGANISATIONS

2.1. Conceptual models of organisational responses to equal opportunities and managing diversity

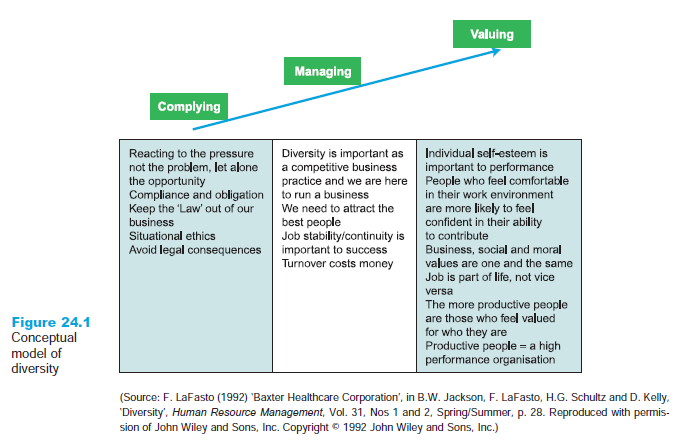

A conceptual model of organisational responses to achieving equality, concentrating on perceived rationale and the differing contributions of equality of opportunity and managing diversity, has been developed by LaFasto (1992). This is shown in Figure 24.1.

An alternative framework is proposed by Jackson et al. (1992) who, concentrating on culture, identify a series of stages and levels that organisations go through in becoming a multicultural organisation.

Level 1, stage 1: the exclusionary organisation

The exclusionary organisation maintains the power of dominant groups in the organisation, and excludes others.

Level 1, stage 2: the club

The club still excludes people but in a less explicit way. Some members of minority groups are allowed to join as long as they conform to predefined norms.

Level 2, stage 3: the compliance organisation

The compliance organisation recognises that there are other perspectives, but does not want to do anything to ‘rock the boat’. It may actively recruit minority groups at the bottom of the organisation and make some token appointments.

Level 2, stage 4: the affirmative action organisation

The affirmative action organisation is committed to eliminating discrimination and encourages employees to examine their attitudes and think differently. There is strong support for the development of new employees from minority groups.

Level 3, stage 5: the redefining organisation

The redefining organisation is not satisfied with being anti-racist and so examines all it does and its culture to see the impact of these on its diverse multicultural workforce. It develops and implements policies to distribute power among all groups.

Level 3, stage 6: the multicultural organisation

The multicultural organisation reflects the contribution and interests of all its diverse members in everything it does and espouses. All members are full participants of the organisation and there is recognition of a broader social responsibility – to educate others outside the organisation and to have an impact on external oppression.

2.2. Equal opportunities and managing diversity: strategies, policies and plans

Kersley et al. (2006) found that 73 per cent of organisations in the Workplace Employee Relations (WER) Survey had equal opportunities or diversity policies or a statement, and this compares with 64 per cent in 1998. The public sector were more likely to have such policies (97 per cent, a level unchanged from the last survey) and larger organisations were more likely to have policies than smaller ones, which means that 88 per cent of the labour force are in organisations where such a policy exists. In addition the existence of a policy was more likely in organisations where there was union recognition. Organisations were more likely to have a policy if they had an employment relations specialist (even allowing for size), a finding confirmed by Woodhams and Lupton (2006) who found that the existence of an HR specialist in small firms increased the likelihood of a policy existing. Clearly the existence of policy or statement depends on the nature of organisations surveyed. It would also be a mistake to assume that all policies cover all potentially disadvantaged groups (see, for example, EOR 1999b), and there is evidence that as legislation begins to cover new groups these are more likely to be covered. Whilst the CIPD (2006b) found that 93 per cent of organisations which responded to its survey did have a diversity policy, the disadadvantaged groups covered by these were very variable, and many did not cover all the groups for whom there is legislative protection.

In the WER Survey the existence of a policy was positively associated with the existence of processes aimed at preventing discrimination such as job evaluation and monitoring of recruitment, selection, promotion and pay. However these activities were still only carried out by a minority of such organisations. Despite the prevalence of policies there is always the concern that having a policy is more about projecting the right image than about reflecting how the organisation operates. For example, Hoque and Noon (1999) found that having an equal opportunities statement made no difference to the treatment of speculative applications from individuals who were either white or from an ethnic minority group and that ‘companies with ethnic minority statements were more likely to discriminate against the ethnic minority applicant’. The Runnymede Trust (2000) in a survey on racial equality found that the way managers explained their equal opportunities policy was different from employee views about what happened in practice. Creegan et al. (2003) investigated the implementation of a race equality action plan and found a stark difference between paper and practice. Line managers who were responsible for implementing the plan were operating in a devolved HR environment and so had to pay for advice, training and support from HR. The consequence of this was that in order to protect their budgets they were reluctant to seek help. Employees felt that there was no ownership of the strategy or the plan within the organisation by senior or middle managers. Woodhams and Lupton (2006) found a disconnection between policy and practice in small organisations, and that whilst the presence of an HR specialist meant policies were more likely, this seemed to have no effect on implementation.

2.3. A process for managing diversity

Ross and Schneider (1992) advocate a strategic approach to managing diversity that is based on their conception of the difference between seeking equal opportunity and managing diversity. The difference, as they see it, is that diversity approaches are:

- internally driven, not externally imposed;

- focused on individuals rather than groups;

- focused on the total culture of the organisation rather than just the systems used;

- the responsibility of all in the organisation and not just the HR function.

Their process involves the following steps:

- Diagnosis of the current situation in terms of statistics, policy and culture, and looking at both issues and causes.

- Setting aims which involve the business case for equal opportunities, identifying the critical role of commitment from the top of the organisation, and a vision of what the organisation would look like if it successfully managed diversity.

- Spreading the ownership. This is a critical stage in which awareness needs to be raised, via a process of encouraging people to question their attitudes and preconceptions. Awareness needs to be raised in all employees at all levels, especially managers, and it needs to be clear that diversity is not something owned by the personnel function.

- Policy development comes after awareness raising as it enables a contribution to be made from all in the organisation – new systems need to be changed via involvement and not through imposition on the unwilling.

- Managing the transition needs to involve a range of training initiatives. Positive action programmes, specifically designed for minority groups, may be used to help them understand the culture of the organisation and acquire essential skills; policy implementation programmes, particularly focusing on selection, appraisal, development and coaching; further awareness training and training to identify cultural diversity and manage different cultures and across different cultures.

- Managing the programme to sustain momentum. This involves a champion, not necessarily from the HR function, but someone who continues in his or her previous organisation role in addition. Also the continued involvement of senior managers is important, together with trade unions. Harnessing initiatives that come up through departments and organising support networks for disadvantaged groups are key at this stage. Ross and Schneider also recommend measuring achievements in terms of business benefit – better relationships with customers, improvements in productivity and profitability, for example – which need to be communicated to all employees.

Ellis and Sonnenfield (1994) make the point that training for diversity needs to be far more than a one-day event. They recommend a series of workshops which allow time for individuals to think, check their assumptions and reassess between training sessions. Key issues that need tackling in arranging training are ensuring that the facilitator has the appropriate skills; carefully considering participant mix; deciding whether the training should be voluntary or mandatory; being prepared to cope with any backlash from previously advantaged groups who now feel threatened; and being prepared for the fact that the training may reinforce stereotypes. They argue that training has enormous potential benefits, but that there are risks involved.

While the ideal may be for organisations to work on all aspects of diversity in an integrated manner, the reality is often that organisations will target specific issues or groups at different times. Case 24.1 on this book’s companion website, www.pearsoned.co.uk/ torrington, is focused on improving diversity practice for people with disabilities.

Changing culture is clearly a key part of any process for managing diversity. In 1995 Her Majesty’s Inspectorate of Constabulary (HMIC) stressed the business case for diversity in the police force. The police force, over a number of years, has made considerable efforts to increase the recruitment and promotion of members of ethnic minorities (see, for example, EOR 1997). It began to tackle the issues of why individuals from different ethnic backgrounds would not even apply to the police for a career (for example, they may be seen, within some ethnic groups, as traitors for doing so). Some progress was made but the Macpherson Report (1999) highlighted the issue of institutional racism, and further efforts were made to reduce discrimination. However, in 2004 there was still clear evidence of discriminatory cultures and attitudes, as evidenced by the television programme about the racist attitudes of new recruits into Manchester police. On Radio 4 on 20 January 2004 the Ali Desai case was discussed and it was argued that the metropolitan police service were racist in the way that they applied discipline to officers, picking up on smaller issues for racial minority groups than for white officers. The changes required to manage diversity effectively should not be underestimated.

Case study 24.2 on the companion website considers the achievement of an ethnic mix on some MBA courses.

Source: Torrington Derek, Hall Laura, Taylor Stephen (2008), Human Resource Management, Ft Pr; 7th edition.

Very great post. I just stumbled upon your weblog and wished to say that I have really loved browsing your blog posts. After all I’ll be subscribing for your feed and I hope you write again soon!