1. THE MILGRAM EXPERIMENTS WITH OBEDIENCE

Obedience is the reaction expected of people by those in authority positions, who prescribe actions which, but for that authority, might not necessarily have been carried out. Stanley Milgram (1974) conducted a classic and controversial series of experiments to investigate obedience to authority and highlighted the significance of obedience and the power of authority in our everyday lives. His work remains a standard explanation of how we all behave.

Subjects were led to believe that a study of memory and learning was being carried out which involved giving progressively more severe electric shocks to a learner who gave incorrect answers to factual questions. If the learner gave the correct answer the reward was a further question; if the answer was incorrect there was the punishment of a mild electric shock. Each shock was more severe than the previous one. The ‘learner’ was not actually receiving shocks, but was a member of the experimental team simulating progressively greater distress, as the shocks were supposedly made stronger. Eighteen different experiments were conducted with over 1,000 subjects, with the circumstances between experiments varying. No matter how the variables were altered the subjects showed an astonishing compliance with authority even when delivering ‘shocks’ of 450 volts. Up to 65 per cent of subjects continued to obey throughout the experiment in the presence of a clear authority figure and as many as 20 per cent continued to obey when the authority figure was absent.

Milgram was dismayed by his results:

With numbing regularity good people were seen to knuckle under to the demands of authority and perform actions that were callous and severe. Men who are in everyday life responsible and decent were seduced by the trappings of authority, by the control of their perceptions, and by the uncritical acceptance of the experimenter’s definition of the situation into performing harsh acts. (1974, p. 123)

Our interest in Milgram’s work is simply to demonstrate that we all have a predilection to obey instructions from authority figures, even if we do not want to. He points out that the act of entering a hierarchical system (such as any employing organisation) makes people see themselves acting as agents for carrying out the wishes of someone else, and this results in these people being in a different state, described as the agentic state. This is the opposite to the state of autonomy when individuals see themselves as acting on their own. Milgram then sets out the factors that lay the groundwork for obedience to authority.

- Family. Parental regulation inculcates a respect for adult authority. Parental injunctions form the basis for moral imperatives, as commands to children have a dual function. ‘Don’t tell lies’ is a moral injunction carrying a further implicit instruction: ‘And obey me!’ It is the implicit demand for obedience that remains the only consistent element across a range of explicit instructions.

- Institutional setting. Children emerge from the family into an institutional system of authority: the school. Here they learn how to function in an organisation. They are regulated by teachers, but can see that the head teacher, the school governors and central government regulate the teachers themselves. Throughout this period they are in a subordinate position. When, as adults, they go to work it may be found that a certain level of dissent is allowable, but the overall situation is one in which they are to do a job prescribed by someone else.

- Rewards. Compliance with authority is generally rewarded, while disobedience is frequently punished. Most significantly, promotion within the hierarchy not only rewards the individual but also ensures the continuity of the hierarchy.

- Perception of authority. Authority is normatively supported: there is a shared expectation among people that certain institutions do, ordinarily, have a socially controlling figure. Also, the authority of the controlling figure is limited to the situation. The usher in a cinema wields authority, which vanishes on leaving the premises. Where authority is expected it does not have to be asserted, merely presented.

- Entry into the authority system. Having perceived an authority figure, an individual must then define that figure as relevant to the subject. The individual not only takes the voluntary step of deciding which authority system to join (at least in most of employment), but also defines which authority is relevant to which event. The fire fighter may expect instant obedience when calling for everybody to evacuate the building, but not if asking employees to use a different accounting system.

- The overarching ideology. The legitimacy of the social situation relates to a justifying ideology. Science and education formed the background to the experiments Milgram conducted and therefore provided a justification for actions carried out in their name. Most employment is in realms of activity regarded as legitimate, justified by the values and needs of society. This is vital if individuals are to provide willing obedience, as it enables them to see their behaviour as serving a desirable end.

Managers are positioned in an organisational hierarchy in such a way that others will be predisposed, as Milgram demonstrates, to follow their instructions. Managers put in place a series of frameworks to explain how they will exact obedience: they use discipline. Because individual employees feel their relative weakness, they seek complementary frameworks to challenge the otherwise unfettered use of managerial disciplinary power: they may join trade unions, but they will always need channels to present their grievances.

In later work Milgram (1992) made an important distinction between obedience and conformity, which had been studied by several experimental psychologists, most notably Asch (1951) and Abrams et al. (1990). Conformity and obedience both involve abandoning personal judgement as a result of external pressure. The external pressure to conform is the need to be accepted by one’s peers and the resultant behaviour is to wear similar clothes, to adopt similar attitudes and adopt similar behaviour. The external pressure to obey comes from a hierarchy of which one is a member, but in which certain others have more status and power than oneself.

There are at least three important differences . . . First, in conformity there is no explicit requirement to act in a certain way, whereas in obedience we are ordered or instructed to do something. Second, those who influence us when we conform are our peers (or equals) and people’s behaviours become more alike because they are affected by example. In obedience, there is . . . somebody in higher authority influencing behaviour. Third, conformity has to do with the psychological need for acceptance by others. Obedience, by contrast, has to do with the social power and status of an authority figure in a hierarchical situation. (Gross and McIlveen 1998, p. 508)

In this chapter we are concerned only with discipline and grievance within business organisations, but it is worth pointing out that managers are the focal points for the grievances of people outside the business as well, but those grievances are called complaints. You may complain about poor service, shoddy workmanship or rudeness from an employee, but you complain to a manager.

HR managers make one of their most significant contributions to business effectiveness by the way they facilitate and administer grievance and disciplinary issues. First, they devise and negotiate the procedural framework of organisational justice on which both discipline and grievance depend. Second, they are much involved in the interviews and problem-solving discussions that eventually produce solutions to the difficulties that have been encountered. Third, they maintain the viability of the whole process which forms an integral part of their work: they monitor to make sure that grievances are not overlooked and so that any general trend can be perceived, and they oversee the disciplinary machinery to ensure that it is not being bypassed or unfairly manipulated.

Grievance and discipline handling is one of the roles in HRM that few other people want to take over. Ambitious line managers may want to select their own staff without HR intervention or by using the services of consultants. They may try to brush their HR colleagues aside and deal directly with trade union officials or organise their own management development, but grievance and discipline is too hot a potato.

The requirements of the law regarding explanation of grievance handling and the legal framework to avoid unfair dismissal combine to make this an area where HR people must be both knowledgeable and effective. That combination provides a valuable platform for influencing other aspects of management. The HR manager who is not skilled in grievance and discipline is seldom in a strong organisational position.

Everything we have said so far presupposes both hierarchy and the use of procedures. You may say that we have already demonstrated that hierarchy is in decline and that there is a preference for more flexible, personal ways of working than procedure offers. Why rely on Milgram’s research, which is now over thirty years old? Surely we have

moved on since then? Our response is simply that hierarchical relationships continue, although deference is in decline. We still seek out the person ‘in authority’ when we have a grievance and managers readily refer problems they cannot resolve to someone else with a more appropriate role. Procedures may be rigid and mechanical, but they are reliable and we use them even if we do not like them.

2. WHAT DO WE MEAN BY DISCIPLINE?

Discipline is regulation of human activity to produce a controlled performance. It ranges from the guard’s control of a rabble to the accomplishment of lone individuals producing spectacular performance through self-discipline in the control of their own talents and resources.

The Advisory, Conciliation and Arbitration Service (ACAS) has produced a code of practice relating to disciplinary procedures which makes precisely this point:

Disciplinary procedures should not be viewed primarily as a means of imposing sanctions [but] … as a way of helping and encouraging improvement amongst employees whose conduct or standard of work is unsatisfactory. (ACAS 2000, p. 6)

First, there is managerial discipline in which everything depends on the leader from start to finish. There is a group of people who are answerable to someone who directs what they should all do. Only through individual direction can that group of people produce a worthwhile performance, like the person leading the community singing in the pantomime or the conductor of an orchestra. Everything depends on the leader.

Second, there is team discipline, where the perfection of the performance derives from the mutual dependence of all, and that mutual dependence derives from a commitment by each member to the total enterprise: the failure of one would be the downfall of all. This is usually found in relatively small working groups, like a dance troupe or an autonomous working group in a factory.

Third, there is self-discipline, like that of the juggler or the skilled artisan, where a solo performer is absolutely dependent on training, expertise and self-control. One of the few noted UK researchers working in the field of discipline concludes that selfdiscipline has recently become much more significant, as demonstrated in the title of his work, ‘Discipline: towards trust and self-discipline’ (Edwards 2000).

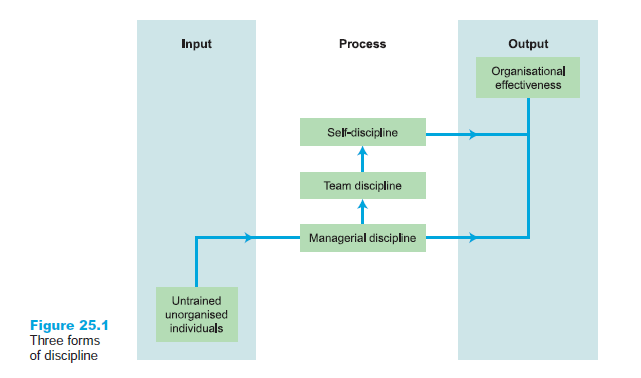

Discipline is, therefore, not only negative, producing punishment or prevention. It can also be a valuable quality for the individual who is subject to it, although the form of discipline depends not only on the individual employee but also on the task and the way it is organised. The development of self-discipline is easier in some jobs than others and many of the job redesign initiatives of recent years have been directed at providing scope for job holders to exercise self-discipline and find a degree of autonomy from managerial discipline. Figure 25.1 shows how the three forms are connected in a sequence or hierarchy, with employees finding one of three ways to achieve their contribution to organisational effectiveness. However, even the most accomplished solo performer has at some time been dependent on others for training and advice, and every team has its coach.

Managers are not dealing with discipline only when they are rebuking latecomers or threatening to dismiss saboteurs. As well as dealing with the unruly and reluctant, they are developing the coordinated discipline of the working team, engendering that esprit de corps which makes the whole greater than the sum of the parts. They are training the new recruit who must not let down the rest of the team, puzzling over the reasons why A is fitting in well while B is still struggling. Managers are also providing people with the equipment to develop the self-discipline that will give them autonomy, responsibility and the capacity to maximise their powers. The independence and autonomy that self-discipline produces also bring the greatest degree of personal satisfaction, and often the largest pay packet. Furthermore the movement between the three forms represents a declining degree of managerial involvement. If you are a leader of community singing, nothing can happen without your being present and the quality of the singing depends on your performance each time. If you train jugglers, the time and effort you invest pays off a thousand times, while you sit back and watch the show.

In employment there has long been an instinctive tendency to put discipline together with punishment, however limited this notion may be. The legislation on unfair dismissal is to most managers the logical final point of disciplinary procedures, yet it covers dismissal on the grounds of capability and ill health as well as more obvious forms of indiscipline. Because of this general feeling that disciplinary procedures imply disobedience, there is an emerging trend to have separate procedures to cover capability, so as to avoid the stigma, but being unsatisfactory in any way is difficult for many people to cope with:

None of the teachers . . . believed they were ‘perfect teachers’ but they refused to equate imperfection with incapability . . . [for example] ‘It was unsatisfactory and obviously I wanted to be satisfactory and above, but it wasn’t poor, it wasn’t incapability material.’ (Torrington 2006, p. 391)

No matter how hard one tries, the prefix ‘in-’ causes problems. To be indisciplined is unwelcome (and does not actually appear in the dictionary): to be incapable is even worse.

3. WHAT DO WE MEAN BY GRIEVANCE?

We can distinguish between the terms dissatisfaction, complaint and grievance as follows:

- Anything that disturbs an employee, whether or not the unrest is expressed in words.

- A spoken or written dissatisfaction brought to the attention of a manager or other responsible person.

- A complaint that has been formally presented to an appropriate management representative or to a union official.

This provides a useful categorisation by separating out grievance as a formal, relatively drastic step, compared with simply complaining. It is much more important for management to know about dissatisfaction. Although nothing is being expressed, the feeling of hurt following failure to get a pay rise or the frustration about shortage of materials can quickly influence performance.

Much dissatisfaction never turns into complaint, as something happens to make it unnecessary. Dissatisfaction evaporates with a night’s sleep, after a cup of coffee with a colleague, or when the cause of the dissatisfaction is in some other way removed. The few dissatisfactions that do produce complaint are also most likely to resolve themselves at that stage. The person hearing the complaint explains things in a way that the dissatisfied employee had not previously appreciated, or takes action to get at the root of the problem.

Grievances are rare since few employees will openly question their superior’s judgement, whatever their private opinion may be, and fewer still will risk being stigmatised as a troublemaker. Also, many people do not initiate grievances because they believe that nothing will be done as a result of their attempt. Tribunal hearings since the 2004 regulations, already referred to, were introduced have often found great difficulty in deciding when a complaint becomes a grievance.

HR managers have to encourage the proper use of procedures to discover sources of dissatisfaction. Managers in the middle may not reveal the complaints they are hearing, for fear of showing themselves in a poor light. Employees who feel insecure, for any reason, are not likely to risk going into procedure, yet the dissatisfaction lying beneath a repressed grievance can produce all manner of unsatisfactory work behaviours from apathy to arson. Individual dissatisfaction can lead to the loss of a potentially valuable employee; collective dissatisfaction can lead to industrial action.

In dealing with complaints it is important to determine what lies behind the complaint as well as the complaint being expressed; not only verifying the facts, which are the manifest content of the complaint, but also determining the feelings behind the facts: the latent content. An employee who complains of the supervisor being a bully may actually be expressing something rather different, such as the employee’s attitude to any authority figure, not simply the supervisor who was the subject of the complaint.

Source: Torrington Derek, Hall Laura, Taylor Stephen (2008), Human Resource Management, Ft Pr; 7th edition.

13 May 2021

11 May 2021

13 May 2021

11 May 2021

11 May 2021

13 May 2021