In the last chapter we looked at situations in which employees decide to end their contracts of employment by giving their employers notice. Here we focus on circumstances when the contract is brought to an end by the employer through a dismissal of one kind or another, something that over a million employees experience in the UK each year (Knight and Latreille 2000). In some cases employees are happy to leave (or at least not unhappy) such as when they are retiring or when they are due to receive a large redundancy payment. More common, however, are situations where the person dismissed is distinctly unhappy about the contract being brought to an end. When someone perceives that they have been treated unfairly in terms of the reason for, or the manner of, their dismissal they can take their case to an employment tribunal. In practice, between five per cent and ten per cent of all dismissed workers who qualify do bring such claims, leaving the Employment Tribunal Service to deal with 30,000-40,000 cases each year (see ETS 2006). If someone wins their case they may ask to be reinstated, but will usually settle for a compensation payment. The size of such awards is not generally substantial (around £8,500 on average), but occasionally people are awarded larger sums. Whatever the final outcome there are often additional legal costs for the employer to bear, not to mention the loss of a great deal of management time. An organisation’s reputation as a good employer can also be damaged by adverse publicity arising from such cases. Employers generally take careful account of the requirements of the law when dismissing employees. The alternative is to run the risk of being summoned to an employment tribunal and possibly losing the case. To a great extent the law therefore effectively determines practice in the field of dismissal.

In the UK there are three forms of dismissal claim that can be brought to a tribunal. Rights associated with the law of wrongful dismissal are the longest established. A person who claims wrongful dismissal complains that the way that they were dismissed breached the terms of their contract of employment. Constructive dismissal occurs when someone feels forced to resign as a direct result of their employer’s actions. In this area the law aims to deter employers from seeking to avoid dismissing people by pushing them into resignation. The third category, unfair dismissal, is by far the most common. It is best defined as a dismissal which falls short of the expectations of the law as laid down in the Employment Rights Act 1996. You will find some practical case study exercises relating to unfair dismissal law on our companion website www.pearsoned.co.uk/torrington.

1. UNFAIR DISMISSAL

The law of unfair dismissal dates from 1971, since when it has been amended a number of times. Although amendments and the outcomes of leading cases have made it more complex than it was originally, the basic principles have stood the test of time and remain in place. The latest major changes were contained in the Statutory Dispute Resolution Regulations which came into effect in 2004 (DTI 2003). Their aim was to reduce the number of claims being brought before employment tribunals by providing strong incentives for employers and employees to make use of internal disciplinary and grievance procedures first. These regulations also adjusted the position of the law in respect of dismissals that are for justified reasons but which are carried out using an incomplete or deficient procedure. At the time of writing (March 2007) the future of the 2004 regulations is in some doubt and it is likely that significant further reform may soon be introduced (see the Window on Practice box).

In most circumstances the right to bring a claim of unfair dismissal applies to employees who have completed a year’s continuous service with their employer on the date their contract was terminated. This allows the employer a period of 12 months to assess whether or not an individual employee is suitable before the freedom to dismiss is restricted. For a number of years until 1999 the time limit was two years. In reducing the period, the government brought an additional 2.8 million people within the scope of unfair dismissal law (DTI 1999). Until recently people who were over the age of 65 or ‘the normal retiring age’ in a particular employment had no right to bring an unfair dismissal case to an employment tribunal. This restriction was removed as part of the introduction of age discrimination law in October 2006. At the time of writing, however (March 2007), it remains lawful for an employer to retire people mandatorily at the age of 65 provided a prescribed procedure is followed.

The one-year restriction on qualification applies except where the reason for the dismissal is one of those listed below which are classed as ‘automatically unfair’ or ‘inadmissible’. A further requirement is that the claim form is lodged at the tribunal office before three months have elapsed from the date of dismissal. Unless there are circumstances justifying the failure to submit a claim before the deadline, claims received after three months are ruled out of time.

Before a case comes to tribunal, officers of the Advisory, Conciliation and Arbitration Service (ACAS) will often try to help the parties reach a settlement. The papers of all cases lodged with the employment tribunals’ offices are sent to ACAS with a view to conciliation taking place ahead of a tribunal hearing. As a result the majority of cases either get settled or are withdrawn without the need for the parties to attend a full hearing.

When faced with a claim of unfair dismissal, and where it is not disputed that a dismissal took place, an employment tribunal asks two separate questions:

- Was the reason for the dismissal one which is classed by the law as legitimate?

- Did the employer act reasonably in carrying out the dismissal?

Where the answer to the first question is ‘no’, there is no need to ask the second because the dismissed employee will already have won his or her case. Interestingly the burden of proof shifts as the tribunal moves from considering the first to the second question. It is for the employer to satisfy the tribunal that it dismissed the employee for a legitimate reason. The burden of proof then becomes neutral when the question of reasonableness is addressed.

1.1. Automatically unfair reasons

Certain reasons for dismissal are declared in law to be inadmissible or automatically unfair. Where the tribunal finds that one of these was the principal reason for the dismissal, they find in favour of the claimant (i.e. the ex-employee) whatever the circumstances of the case. In practice, therefore, there is no defence that an employer can make to explain its actions that will be acceptable to the tribunal. Some of these relate to other areas of employment law such as non-discrimination, working time and the minimum wage, which are discussed in more detail elsewhere in this book. The list of automatically unfair reasons for dismissal has grown steadily in recent years as new employment rights have come on to the statute book; in 2007 it was as follows:

- dismissal for a reason relating to pregnancy or maternity;

- dismissal for a health and safety reason (e.g. refusing to work in unsafe conditions);

- dismissal because of a spent conviction;

- dismissal for refusing to work on a Sunday (retail and betting workers only);

- dismissal for a trade union reason;

- dismissal for taking official industrial action (during the first 12 weeks of the action);

- dismissal in contravention of the part-time workers or fixed-term employees’ regulations;

- dismissal for undertaking duties as an occupational pension fund trustee, employee representative, member of a European Works Council or in connection with jury service;

- dismissal for asserting a statutory right (including rights exercised under the Employment Rights Act, as well as those connected with the Working Time Regulations, the National Minimum Wage Regulations, the Public Interest Disclosure Act and the Information and Consultation of Employees Regulations; the right to request flexible working, the right to time off for dependents, the right to adoptive, parental or paternity leave, the right to be accompanied at disciplinary and grievance hearings and the claiming of working tax credits);

- dismissal for a reason connected with the transfer of an undertaking (i.e. when a business or part of a business changes hands or merges with another organisation) in the absence of a valid economic, technical or organisational reason;

- dismissals that take place before the completion of the disciplinary and dismissal procedures (DDPs) required by the Dispute Resolution Regulations 2004.

The requirement to have completed a year’s continuous service only applies in the case of the last two dismissal scenarios on this list. Under the Dispute Resolution Regulations 2004 a dismissal must be found unfair, irrespective of the circumstances, whenever an employer dismisses an employee with over a year’s service without first having initiated the following basic three-step procedure:

- Step 1: The employer sends the employee a letter setting out the nature of the circumstances that may lead to the employee’s dismissal.

- Step 2: The employer invites the employee to a meeting to discuss the issue at which both parties put their views across. After the meeting the employer informs the employee about the outcome. If it is to dismiss, then the right of appeal is confirmed.

- Step 3: The employee exercises their right to appeal and a further meeting is held for this purpose.

In exceptional cases of gross misconduct employers are permitted to omit stage 2 of this procedure. This does not, however, make the dismissal fair, it just means that it is not automatically unfair. A failure to investigate properly or hold a hearing would mean that such a dismissal would usually be found to have been carried out unreasonably.

1.2. Potentially fair reasons

From an employer’s perspective it is important to be able to satisfy the tribunal that the true reason for the dismissal was one of those reasons classed as potentially fair in unfair dismissal law. Only once this has been achieved can the second question (the issue of reasonableness) be addressed. The potentially fair grounds for dismissal are as follows:

- Lack of capability or qualifications: if an employee lacks the skill, aptitude or physical health to carry out the job, then there is a potentially fair ground for dismissal.

- Misconduct: this category covers the range of behaviours that we examine in considering the grievance and discipline processes: disobedience, absence, insubordination and criminal acts. It can also include taking industrial action.

- Redundancy: where an employee’s job ceases to exist, it is potentially fair to dismiss the employee for redundancy.

- Statutory bar: when employees cannot continue to discharge their duties without breaking the law, they can be fairly dismissed. Most cases of this kind follow disqualification of drivers following convictions for speeding, or for drunk or dangerous driving. Other common cases involve foreign nationals whose work permits have been terminated.

- Some other substantial reason: this most intangible category is introduced in order to cater for genuinely fair dismissals for reasons so diverse that they could not realistically be listed. Examples have been security of commercial information (where an employee’s husband set up a rival company) or employee refusal to accept altered working conditions.

- Dismissals arising from official industrial action after 12 weeks have passed.

- Dismissals that occur on the transfer of an undertaking where a valid ETO (economic, technological or organisational) reason applies.

- Mandatory retirements which follow the completion of the procedures set out in the Employment Equality (Age) Regulations 2006 (see Chapter 23).

1.3. Determining reasonableness

Having decided that potentially fair grounds for the dismissal exist, the tribunal then proceeds to consider whether the dismissal is fair in the circumstances. The test used by the tribunal in reaching decisions about the fairness of a dismissal is that of the

reasonable employer. Tribunal members are not required to judge cases on the basis of what they would have done in the circumstances or what the best employers would have done. Instead they have to ask themselves whether what the employer did in the circumstances of the time fell within a possible band of reasonable responses. In practice this means that the employer wins the case if it can show that the decision to dismiss was one that a reasonable employer might conceivably have taken.

In assessing reasonableness tribunals always take a particular interest in the procedure that was used. They are also keen to satisfy themselves that the employer has acted broadly consistently in its treatment of different employees and that it has taken into account any mitigating circumstances that might have explained a deterioration in an employee’s conduct or performance. In addition, they are required to have regard to the size and resources of the employer concerned. Higher standards are thus expected of a large PLC with a well-staffed HR department than of a small owner-managed business employing a handful of people. The former, for example, might be expected to give two or three warnings and additional training before dismissing someone on grounds of incapability. One simple warning might suffice in a small business which relied heavily on an acceptable level of performance from the individual concerned.

The significance attached to procedure has varied over the years. Until 1987 employers were able to argue successfully that although the procedure used was deficient in some respects, the outcome was not affected. This changed following the judgment of the House of Lords in the case of Polkey v. AE Dayton Services (1987). Henceforth, tribunals were obliged to find dismissals unfair where the employer had not completed a proper procedure before making the final decision to dismiss. In 2004 the law changed again, but the extent to which this has occurred has only become clear more recently as a result of evolving case law. The current position is that the employer must only dismiss once the basic two or three-step procedure set out in the 2004 Dispute Resolution Regulations has been completed. A failure to do so renders the dismissal automatically unfair. However, beyond that, procedural deficiencies can be defended on the grounds that they made no difference to the outcome. In other words, a dismissal would have occurred whether or not the employers’ own established procedures were or were not carried through to the letter.

In this book we have separated the consideration of discipline from the consideration of dismissal in order to concentrate on the practical aspects of discipline (putting things right) rather than the negative aspects (getting rid of the problem). The two cannot, however, be separated in practice and the question of dismissal needs to be reviewed in the light of the material in Chapter 25.

1.4. Lack of capability or qualifications

A common reason for dismissal is poor performance on the part of an employee. The law permits dismissals for this reason. It also allows employers to determine for themselves what constitutes an acceptable level of performance in a job, provided of course that a consistent approach is followed between different employees. However, such dismissals are only considered to be reasonable (and hence fair in law) if the employee concerned has both been formally warned about their poor performance at least once and given a reasonable opportunity to improve. Formality in this context means that a formal hearing has been held at which the employee has been entitled to be represented and after which there has been a right of appeal to a more senior manager.

The employer will always need to demonstrate the employee’s unsuitability to the satisfaction of the tribunal by producing evidence of that unsuitability. This evidence must not be undermined by, for instance, giving the employee a glowing testimonial at the time of dismissal or by the presence of positive appraisal reports on the individual’s personal file. Lack of skill or aptitude is a fair ground when the lack can be demonstrated and where the employer has not contributed to it by, for instance, ignoring it for a long period. Redeployment to a more suitable job is also an option employers are expected to consider before taking the decision to dismiss.

The requirement on employers to warn an employee formally that their performance is unsatisfactory at a meeting at which they have the opportunity to answer back, and the subsequent requirement to give the employee concerned support during a reasonable period in which they have an opportunity to improve, means that dismissals on grounds of poor performance can take several weeks or months to carry through. Moreover, during this time relationships can become very strained because formal action has been taken and a formal warning given. For these reasons managers often seek to avoid dismissing in line with the expectations of the law, instead seeking to dress up poor performance dismissals as redundancies or cases of gross misconduct. However, employment tribunals are very aware of this tendency and always find dismissals that occur in such circumstances to be unfair.

Another aspect of employee capability is health. It is potentially fair to dismiss someone on the grounds of ill health which renders the employee incapable of discharging the contract of employment. Even the most distressing dismissal can be legally admissible, provided that it is not too hasty and that there is consideration of alternative employment. Employers are expected, however, to take account of any medical advice available to them before dismissing someone on the grounds of ill health. Companies with occupational health services are well placed to obtain detailed medical reports to help in such judgements but the decision to terminate someone’s employment is ultimately for the manager to take and, if necessary, to justify at a tribunal. Medical evidence will be sought and has to be carefully considered but dismissal remains an employer’s decision, not a medical decision.

Normally, absences through sickness have to be frequent or prolonged in order for dismissal on the grounds of such absence to be judged fair, although absence which seriously interferes with the running of a business may be judged fair even if it is neither frequent nor prolonged. In all cases the employee must be consulted and effectively warned before being dismissed.

In the leading case of Egg Stores v. Leibovici (1977) the EAT set out nine questions that have to be asked to determine the potential fairness of dismissing someone after long-term sickness:

how long has the employment lasted; (b) how long had it been expected the employment would continue; (c) what is the nature of the job; (d) what was the nature, effect and length of the illness; (e) what is the need of the employer for the work to be done, and to engage a replacement to do it; (f) if the employer takes no action, will he incur obligations in respect of redundancy payments or compensation for unfair dismissal; (g) are wages continuing to be paid; (h) why has the employer dismissed (or failed to do so); and (i) in all the circumstances, could a reasonable employer have been expected to wait any longer?

A different situation is where an employee is frequently absent for short spells. Here too it is potentially reasonable to dismiss, but only after proper consideration of the illnesses and after warning the employee of the consequences if their attendance record does not improve. Each case has to be decided on its own merits. Medical evidence must be sought and a judgement reached about how likely it is that high levels of absence will continue in the future. The fact that an employee is wholly fit at the time of his or her dismissal does not mean that it is necessarily unfair. What matters is the overall attendance record and its impact on the organisation.

In another leading case, that of International Sports Ltd v. Thomson (1980), the employer dismissed an employee who had been frequently absent with a series of minor ailments ranging from althrugia of one knee, anxiety and nerves to bronchitis, cystitis, dizzy spells, dyspepsia and flatulence. All of these were covered by medical notes. (While pondering the medical note for flatulence, you will be interested to know that althrugia is water on the knee.) The employer issued a series of warnings and the company dismissed the employee after consulting its medical adviser, who saw no reason to examine the employee as the illnesses had no connecting medical theme and were not chronic. The Employment Appeals Tribunal held that this dismissal was fair because proper warning had been given and because the attendance record was deemed so poor as not to be acceptable to a reasonable employer. This position was confirmed by the Court of Appeal in Wilson v. The Post Office (2000) where it was held to be quite acceptable, in principle, for an employer to dismiss someone simply because of a poor absence record.

The law on ill-health dismissals was affected in important ways by the passing of the Disability Discrimination Act 1995. In Chapter 23 we look at this important piece of legislation in detail. Here it is simply necessary to state that dismissing someone who is disabled according to the definition given in the Act, without first considering whether adjustments to working practices or the working environment would allow them to continue working, is unlawful. Reasonable adjustments might well include tolerance of a relatively high level of absence, especially where the employer is large enough to be able to cope perfectly well in the circumstances. Employers are well advised to pay particular attention to disability discrimination issues when dismissing people on the grounds of ill health because the level of compensation that can be awarded by tribunals in such cases is considerably higher than it is for unfair dismissal.

1.5. Misconduct

The law expects employers to make a distinction between two classes of misconduct when dismissing employees or considering doing so.

- Gross misconduct. This occurs when an employee commits an offence which is sufficiently serious to justify summary dismissal. To qualify, the employee must have acted in such a way as to have breached either an express term of their contract or one of the common law duties owed by an employee to an employer (see Chapter 6). In practice this means that their actions must be ‘intolerable’ for any reasonable employer.

- Ordinary misconduct. This involves lesser transgressions, such as minor breaches of rules and relatively insignificant acts of disobedience, insubordination, lateness, forgetfulness or rudeness. In such cases the employer is deemed by the courts to be acting unreasonably if it dismisses as a result of a first offence. The dismissal would only be fair if, having been formally warned at least once, the employee failed to improve his/her conduct.

Employers have a wide degree of discretion when it comes to deciding what exactly does and does not constitute gross misconduct, and this will vary from workplace to workplace. For example, a distinction can be made between uttering an obscene swear word in front of colleagues (ordinary misconduct) and swearing obscenely to a customer (gross misconduct). While much depends on the circumstances, the tribunals also look carefully at an employer’s established policies on matters of conduct:

Where the disciplinary rules spell out clearly the type of conduct that will warrant dismissal then a dismissal for this reason may be fair. Conversely, if the rules are silent or ambiguous as to whether particular conduct warrants dismissal, a dismissal for a first offence may be unfair. It is important, therefore, for employers to set out in writing what standards of conduct they expect, to make clear what will be regarded as ‘sackable misconduct’, and to ensure that everyone is aware of these rules. (Duggan 1999, p. 178)

The second key principle in misconduct cases concerns procedure. Whether the individual is dismissed summarily for gross misconduct or after a number of warnings for ordinary misconduct, the tribunals look to see if a reasonable procedure has been used. This basic requirement is unaffected by the Dispute Resolution Regulations (2004) which clearly state that employers are required to adhere to basic procedures. However, these regulations do permit employers to dispense with the need for a disciplinary hearing in ‘extreme’ cases of gross misconduct. We look in more detail at disciplinary procedures in Chapter 25. Here it is necessary to note the main questions that an employment tribunal asks when faced with such cases:

- Was the accusation thoroughly, promptly and properly investigated by managers before the decision was made to dismiss or issue a formal warning?

- Was a formal hearing held at which the accused employee was given the opportunity to state their case and challenge evidence brought forward by managers?

- Was the employee concerned permitted to be represented at the hearing by a colleague or trade union representative?

- Was the employee treated consistently when compared with other employees who had committed similar acts of misconduct in the past?

Only if the answers to all these questions is ‘yes’ will a tribunal find a dismissal fair. They do not, however, expect employers to adhere to very high standards of evidence gathering such as those employed by the police in criminal investigations. Here, as throughout employment law, the requirement is for the employer to act reasonably in all the circumstances, conforming to the principles of natural justice and doing what it thought to be right at the time, given the available facts.

Conversely, if an employee is found guilty by court proceedings, this does not automatically justify fair dismissal; it must still be procedurally fair and reasonable. A theft committed off duty and away from the workforce is not necessarily grounds for dismissal; it all depends on the nature of the work carried out by the employee concerned. For example, it might well be reasonable to dismiss members of staff with responsibility for cash if they commit an offence of dishonesty while off duty.

On the other hand, evidence that would not be sufficient to bring a prosecution may be sufficient to sustain a fair dismissal. Clocking-in offences will normally merit dismissal. Convictions for other offences like drug handling or indecency will only justify dismissal if the nature of the offence will have some bearing on the work done by the employee. For someone like an instructor of apprentices it might justify summary dismissal, but in other types of employment it would be unfair, just as it would be unfair to dismiss an employee for a driving offence when there was no need for driving in the course of normal duties and there were other means of transport for getting to work.

1.6. Redundancy

Dismissal for redundancy is protected by compensation for unfair redundancy, compensation for genuine redundancy and the right to consultation before the redundancy takes place:

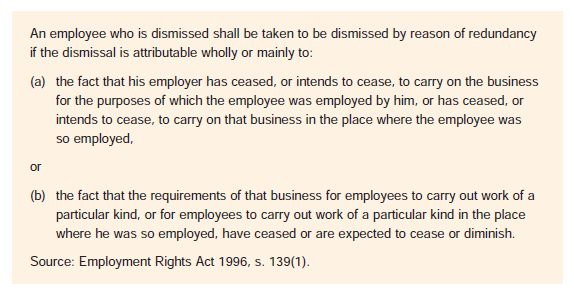

An employee who is dismissed shall be taken to be dismissed by reason of redundancy

Apart from certain specialised groups of employees, anyone who has been continuously employed for two years or more is guaranteed a compensation payment from an employer, if dismissed for redundancy. The compensation is assessed on a sliding scale relating to length of service, age and rate of pay per week. If the employer wishes

to escape the obligation to compensate, then it is necessary to show that the reason for dismissal was something other than redundancy. The inclusion of age in the criteria for calculating redundancy payments remained, despite the introduction of age discrimination law in 2006.

Although the legal rights relating to redundancy have not altered for 35 years, there have been persistent problems of interpretation, different courts reaching different decisions when faced with similar sets of circumstances (see IRS 2000b). In 1999 the House of Lords provided some long-needed clarification of key issues in the cases of Murray et al. v. Foyle Meats Ltd, where it was decided that tribunals should look at the actual facts of someone’s working situation rather than at their written contractual terms when deciding whether or not their jobs were redundant. In so doing it confirmed that the practice of ‘bumping’, where the employer dismisses a person whose job is remaining to retain the services of another employee whose job is disappearing, is acceptable under the statutory definition. The questions laid out by the Employment Appeals Tribunal (EAT) in Safeway v. Burrell (1997) are thus now confirmed as those that tribunals should ask when considering these cases:

- Has the employee been dismissed?

- Has there been an actual or prospective cessation or diminution in the requirements for employees to carry out work of a particular kind?

- Is the dismissal wholly or mainly attributable to the state of affairs?

The employer has to consult with the individual employee before dismissal takes place, but there is also a separate legal obligation to consult with recognised trade unions or some other body of employee representatives where no union is recognised. If 20 or more employees are to be made redundant, then the employer must give written notice of intention to any recognised unions concerned and the Department for Business, Enterprise and Regulatory Reform (DBERR) at least 30 days before the first dismissal. If it is proposed to make more than 100 employees redundant within a three-month period, then 90 days’ advance notice must be given. Having done this, the employer has a legal duty to consult on the redundancies. There is no obligation to negotiate with employees, merely to explain, listen to comments and reply with reasons. Employees also have the right to reasonable time off with pay during their redundancy notice so that they can seek other work.

One of the most difficult aspects of redundancy for the employer is the selection of who should go. The traditional approach provides that people should leave on a last-infirst-out basis, or LIFO, as this provides a rough-and-ready justice with which it is difficult to argue. In recent years, however, an increasing number of employers are using a mix of other criteria, including skill, competence and attendance record. A third approach involves drawing up a new post-redundancy organisation structure and inviting everyone to apply for the jobs that will remain. All three approaches are widely used and have been considered acceptable as far as the law is concerned provided they are carried out objectively and consistently. However, some commentators question whether or not LIFO is compatible with age discrimination law on the grounds that it inevitably involves favouring older employees over younger colleagues and is not always objectively justifiable.

Increasingly, employers are trying to avoid enforced redundancy by a range of strategies, such as not replacing people who leave, early retirement and voluntary redundancy. They also increasingly seek to make the management of redundancy more palatable by appointing redundancy counselling or outplacement services. Sometimes this is administered by the HR department, but many organisations use external services. Contrary to some popular perception there is no legal requirement to offer such services or to ask for volunteers before carrying through a programme of compulsory redundancies.

1.7. Some other substantial reason

As the law of unfair dismissal has evolved since 1971 the most controversial area has been the category of potentially fair dismissals known as ‘some other substantial reason’. Many commentators see this as a catch-all or dustbin category which enables employers to dismiss virtually anyone provided a satisfactory business case can be made. All manner of cases have been successfully defended under this heading including the following: dismissals resulting from personality clashes, pressure to dismiss from subordinates or customers, disclosure of damaging information, the dismissal of a man whose wife worked for a rival firm, and the dismissal of a landlord’s wife following her husband’s dismissal on grounds of capability.

The majority of cases brought under this heading, however, result from business reorganisations where there is no redundancy. These often occur when the employer seeks to alter terms and conditions of employment and cannot secure the employee’s agreement. Such circumstances can result in the dismissal of the employee together with an offer of re-employment on new contractual terms. Such dismissals are judged fair provided a sound business reason exists to justify the changes envisaged. It will usually be necessary to consult prior to the reorganisation but the tribunal will not base its judgment on whether the employee acted reasonably in refusing new terms and conditions. The test laid down in Hollister v. The National Farmers’ Union (1979) by the Court of Appeal merely requires the employer to demonstrate that the change would bring clear organisational advantage.

1.8. Written statement of reasons

The Employment Rights Act 1996 (s. 92) gives employees the right to obtain from their employer a written statement of the reasons for their dismissal if they are dismissed after completing a year’s continuous service. If asked, the employer must provide the statement within 14 days. If it is not provided, the employee can complain to an employment tribunal that the statement has been refused and the tribunal will award the employee two weeks’ pay if they find the complaint justified. The same right applies where a fixed- term contract is not renewed after having expired. The employee can also complain, and receive the same award, if the employer’s reasons are untrue or inadequate, provided that the tribunal agrees.

Such an award is in addition to anything the tribunal may decide about the unfairness of the dismissal, if the employee complains about that. The main purpose of this provision is to enable the employee to test whether there is a reasonable case for an unfair dismissal complaint or not. Although the statement is admissible as evidence in tribunal proceedings, the tribunal will not necessarily be bound by what the statement contains. If the tribunal members were to decide that the reasons for dismissal were other than stated, then the management case would be jeopardised.

2. CONSTRUCTIVE DISMISSAL

When the conduct of the employer causes an employee to resign, the ex-employee may still be able to claim dismissal on the grounds that the behaviour of the employer constituted a repudiation of the contract, leaving the employee with no alternative but to resign. The employee may then be able to claim that the dismissal was unfair. It is not sufficient for the employer simply to be awkward or whimsical; the employer’s conduct must amount to a significant breach, going to the root of the contract, such as physical assault, demotion, reduction in pay, change in location of work or significant change in duties. The breach must, however, be significant, so that a slight lateness in paying wages would not involve a breach, neither would a temporary change in place of work.

Some of the more interesting constructive dismissal cases concern claims that implied terms of contract have been breached, such as the employer’s duty to maintain safe systems of working or mutual trust and confidence.

Constructive dismissal, like unfair dismissal, dates from 1971. It too only applies to employees who have completed a year’s continuous service. The cases are harder for employees to win and easier for employers to defend because of the need to establish that a dismissal has taken place, before issues of reasonableness in the circumstances are addressed. The burden of proof is on the employee to show that they were forced into resigning as a result of a repudiatory breach on the part of the employer.

3. COMPENSATION FOR DISMISSAL

Having found in favour of the applicant in cases of unfair or constructive dismissal, the tribunal can make two types of decision: either they can order that the ex-employee be reemployed or they can award some financial compensation from the ex-employer for the loss that the employee has suffered. Originally it was intended that re-employment should be the main remedy, although this was not previously available under earlier legislation. In practice, however, the vast majority of ex-employees (over 98 per cent) want compensation.

Tribunals will not order re-employment unless the dismissed employee wants it, and tribunals can choose between reinstatement or re-engagement. In reinstatement the old job is given back to the employee under the same terms and conditions, plus any increments, etc., to which the individual would have become entitled had the dismissal not occurred, plus any arrears of payment that would have been received. The situation is just as it would have been, including all rights deriving from length of service, if the dismissal had not taken place. The alternative of re-engagement will be that the employee is employed afresh in a job comparable to the last one (usually in a different department), but without continuity of employment. The decision as to which of the two to order will depend on assessment of the practicability of the alternatives, the wishes of the unfairly dismissed employee and the natural justice of the award taking account of the ex-employee’s behaviour.

Tribunals currently calculate the level of compensation under a series of headings. First is the basic award which is based on the employee’s age and length of service. It is calculated in the same way as statutory redundancy payments, and like them has not been changed following the introduction of age discrimination law:

- half a week’s pay for every year of service below the age of 22;

- one week’s pay for every year of service between the ages of 22 and 41;

- one and a half weeks’ pay for every year of service over the age of 41.

The basic award is limited, however, because tribunals can only take into account a maximum of 20 years’ service when calculating the figure to be awarded. A maximum weekly salary figure is also imposed by the Treasury. This was £310 in 2007. The maximum basic award that can be ordered is therefore £9,300. In many cases, of course, where the employee has only a few years’ service the figure will be far lower. In addition a tribunal can also order compensation under the following headings:

- Compensatory awards take account of loss of earnings, pension rights, future earnings loss, etc. The maximum level in 2007 was £60,600.

- Additional awards are used in cases of sex and race discrimination and also when an employer fails to comply with an order of reinstatement or re-engagement. In the former case the maximum award is 52 weeks’ pay, in the latter 26 weeks’ pay.

- Special awards are made when unfair dismissal relates to trade union activity or membership. They can also be used when the dismissal was for health and safety reasons.

A tribunal can reduce the total level of compensation if it judges the individual concerned to have contributed to his or her own dismissal. For example, a dismissal on grounds of poor work performance may be found unfair because no procedure was followed and consequently no warnings given. This does not automatically entitle the ex-employee concerned to compensation based on the above formulae. If the tribunal judges the ex-employee to have been 60 per cent responsible for his or her own dismissal the compensation will be reduced by 60 per cent. Reductions are also made if an ex-employee is judged not to have taken reasonable steps to mitigate his or her loss.

4. WRONGFUL DISMISSAL

In addition to the body of legislation defining unfair and constructive dismissal there is a long-standing common law right to damages for an employee who has been dismissed wrongfully.

Cases of wrongful dismissal are taken to employment tribunals where the claim is for less than £25,000; otherwise they are taken to the county court. These cases are concerned solely with alleged breaches of contract. Employees can thus only bring cases of wrongful dismissal against their employers when they believe their dismissal to have been unlawful according to the terms of their contract of employment. Wrongful dismissal can, therefore, be used when the employer has not given proper notice or if the dismissal is in breach of any clause or agreement incorporated into the contract. This remains a form of remedy that very few people use, but it could be useful to employees who do not have sufficient length of service to claim unfair dismissal and whose contracts include the right to a full disciplinary procedure. There may also be cases where a very highly paid employee might get higher damages in an ordinary court than the maximum that the tribunal can award.

5. NOTICE

An employee qualifies for notice of dismissal on completion of four weeks of employment with an employer. At that time the employee is entitled to receive one week’s notice. This remains constant until the employee has completed two years’ service, after which it increases to two weeks’ notice, thereafter increasing on the basis of one week’s notice per additional year of service up to a maximum of 12 weeks for 12 years’ unbroken service with that employer. These are minimum statutory periods. If the employer includes longer periods of notice in the contract, which is quite common with senior employees, then they are bound by the longer period.

The employee is required to give one week’s notice after completing four weeks’ service and this period does not increase as a statutory obligation. If an employee accepts a contract in which the period of notice to be given is longer, then that is binding, but the employer may have problems of enforcement if an employee is not willing to continue in employment for the longer period.

Neither party can withdraw notice unilaterally. The withdrawal will be effective only if the other party agrees. Therefore, if an employer gives notice to an employee and wishes later to withdraw it, this can be done only if the employee agrees to the contract of employment remaining in existence. Equally, employees cannot change their minds about resigning unless the employer agrees.

Notice exists when a date has been specified. The statement ‘We’re going to wind up the business, so you will have to find another job’ is not notice: it is a warning of intention.

Source: Torrington Derek, Hall Laura, Taylor Stephen (2008), Human Resource Management, Ft Pr; 7th edition.

I was very pleased to find this web-site.I wanted to thanks for your time for this wonderful read!! I definitely enjoying every little bit of it and I have you bookmarked to check out new stuff you blog post.