1. TURNOVER ANALYSIS AND COSTING

There is little that an organisation can do to manage turnover unless there is an understanding of the reasons for it. Information about these reasons is notoriously difficult to collect. Most commentators recommend exit interviews (that is, interviews with leavers about their reasons for resigning), but the problem here is whether the individual will feel able to tell the truth, and this will depend on the culture of the organisation, the specific reasons for leaving and support that the individual will need from the organisation in the future in the form of references. Despite their disadvantages, exit interviews may be helpful if handled sensitively and confidentially – perhaps by the HR department rather than the line manager. You will find further information and discussion exercises about them on our companion website www.pearsoned.co.uk/torrington. In addition, analyses of turnover rates between different departments and different job groups may well shed some light on causes of turnover. Attitude surveys can also provide relevant information.

People leave jobs for a variety of different reasons, many of which are wholly outside the power of the organisation to influence. One very common reason for leaving, for example, is retirement. It can be brought forward or pushed back for a few years, but ultimately it affects everyone. In many cases people leave for a mixture of reasons, certain factors weighing more highly in their minds than others. The following is one approach to categorising the main reasons people have for voluntarily leaving a job, each requiring a different kind of response from the organisation.

1.1. Outside factors

Outside factors relate to situations in which someone leaves for reasons that are largely unrelated to their work. The most common instances involve people moving away when a spouse or partner is relocated. Others include the wish to fulfil a long-term ambition to travel, pressures associated with juggling the needs of work and family and illness. To an extent such turnover is unavoidable, although it is possible to reduce it somewhat through the provision of career breaks, forms of flexible working and/or childcare facilities.

1.2. Functional turnover

The functional turnover category includes all resignations which are welcomed by both employer and employee alike. The major examples are those which stem from an individual’s poor work performance or failure to fit in comfortably with an organisational or departmental culture. While such resignations are less damaging than others from an organisation’s point of view they should still be regarded as lost opportunities and as an unnecessary cost. The main solution to the reduction of functional turnover lies in improving recruitment and selection procedures so that fewer people in the category are appointed in the first place. However, some poorly engineered change management schemes are also sometimes to blame, especially where they result in new work pressures or workplace ethics.

1.3. Push factors

With push factors the problem is dissatisfaction with work or the organisation, leading to unwanted turnover. A wide range of issues can be cited to explain such resignations. Insufficient development opportunities, boredom, ineffective supervision, poor levels of employee involvement and straightforward personality clashes are the most common precipitating factors. Organisations can readily address all of these issues. The main reason that so many fail to do so is the absence of mechanisms for picking up signs of dissatisfaction. If there is no opportunity to voice concerns, employees who are unhappy will inevitably start looking elsewhere.

1.4. Pull factors

The opposite side of the coin is the attraction of rival employers. Salary levels are often a factor here, employees leaving in order to improve their living standards. In addition there are broader notions of career development, the wish to move into new areas of work for which there are better opportunities elsewhere, the chance to work with particular people, and more practical questions such as commuting time. For the employer losing people as a result of such factors there are two main lines of attack. First, there is a need to be aware of what other employers are offering and to ensure that as far as

possible this is matched – or at least that a broadly comparable package of pay and opportunities is offered. The second requirement involves trying to ensure that employees appreciate what they are currently being given. The emphasis here is on effective communication of any ‘unique selling points’ and of the extent to which opportunities comparable to those offered elsewhere are given.

1.5. What are the most common reasons?

Taylor and his colleagues (2002) interviewed 200 people who had recently changed employers about why they left their last jobs. They found a mix of factors at work in most cases but concluded that push factors were a great deal more prevalent than pull factors as causes of voluntary resignations. Very few people appear to leave jobs in which they are broadly happy in search of something even better. Instead the picture is overwhelmingly one in which dissatisfied employees seek alternatives because they no longer enjoy working for their current employer.

Interestingly this study found relatively few examples of people leaving for financial reasons. Indeed more of the interviewees took pay cuts in order to move from one job to another than said that a pay rise was their principal reason for switching employers. Other factors played a much bigger role:

- dissatisfaction with the conditions of work, especially hours;

- a perception that they were not being given sufficient career development opportunities;

- a bad relationship with their immediate supervisor.

This third factor was by far the most commonly mentioned in the interviews, lending support to the often stated point that people leave their managers and not their organisations.

Branham (2005), drawing on research undertaken by the Saratoga Institute, reached similar conclusions. His seven ‘hidden reasons employees leave’ are as follows:

- the job or workplace not living up to expectations;

- a mismatch between the person and the job;

- too little coaching and feedback;

- too few growth and advancement opportunities;

- feeling devalued and unrecognised;

- stress from overwork and work-life imbalance;

- loss of trust and confidence in senior leaders.

You will find further information and discussion exercises about the issue of trust and its link to employee retention on our companion website www.pearsoned.co.uk/torrington.

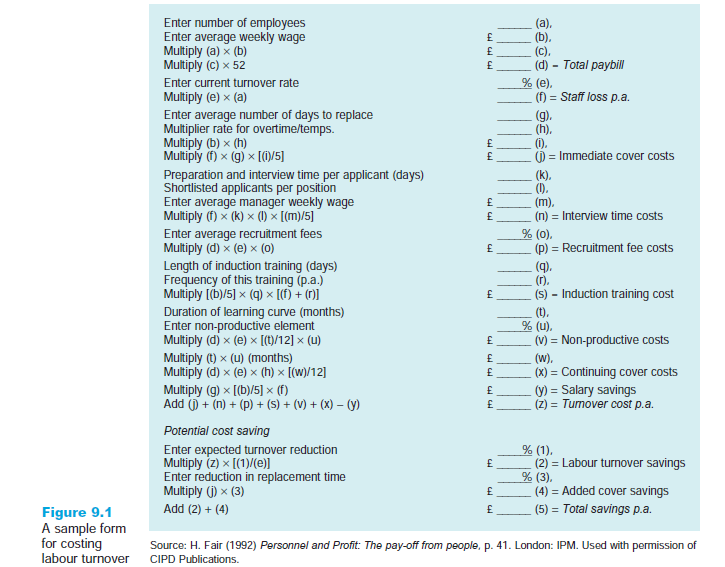

1.6. Costing

When deciding what kind of measures to put in place in order to improve staff retention generally or the retention of particular individuals, organisations need to balance the costs involved against those that are incurred as a direct result of voluntary resignations. Although it is difficult to cost turnover accurately, it is possible to reach a fair estimate by taking into account the range of expenses involved in replacing one individual with another. Once a figure has been calculated for a job, it is relatively straightforward to compute the savings to be gained from a given percentage reduction in annual turnover rates. Figure 9.1 shows the approach to turnover costing recommended by Hugo Fair (1992).

Costing turnover each year permits organisations to state with some confidence how much money is being saved as a result of ongoing staff turnover reduction programmes. It can also be used as a means of persuading finance directors of the case for investing money in initiatives which can be shown to improve retention. An example of an organisation which has done this is Positive Steps Oldham, a not-for-profit company set up when two local careers service organisations merged (see IDS 2005). The new organisation employs 205 people and at the time it was formed had an overall staff turnover rate of 38 per cent. Over a three-year period, as a result of various targeted initiatives, turnover fell to a much more healthy 14 per cent. Not only did this make the organisation much more effective, it also substantially reduced overheads. The company model for calculating turnover costs includes direct and indirect costs along the lines put forward by Fair in Figure 9.1. At Positive Steps Oldham it was estimated that around £20,000 a year was saved by more than halving turnover.

2. STAFF RETENTION STRATEGIES

The straightforward answer to the question of how best to retain staff is to provide them with a better deal, in the broadest sense, than they perceive they could get by working for alternative employers. Terms and conditions play a significant role, but other factors are often more important. For example, there is a need to provide jobs which are satisfying, along with career development opportunities, as much autonomy as is practicable and, above all, competent line management. Indeed, at one level, most of the practices of effective human resource management described in this book can play a part in reducing turnover. Organisations which make use of them will enjoy lower rates than competitors who do not. Below we look at six measures that have been shown to have a positive effect on employee retention, focusing particularly on those practices which are not covered in any great depth elsewhere in the book.

2.1. Pay

There is some debate in the retention literature about the extent to which raising pay levels reduces staff turnover. On the one hand there is evidence to show that, on average, employers who offer the most attractive reward packages have lower attrition rates than those who pay poorly (Gomez-Mejia and Balkin 1992, pp. 292-4), an assumption which leads many organisations to use pay rates as their prime weapon in retaining staff (Cappelli 2000, pp. 105-6; IRS 2000a, p. 10; IRS 2000b, p. 9). On the other, there is questionnaire-based evidence which suggests that pay is a good deal less important than other factors in a decision to quit one’s job (Bevan et al. 1997, p. 25; Hiltrop 1999, p. 424). The consensus among researchers specialising in retention issues is that pay has a role to play as a satisfier, but that it will not usually have an effect when other factors are pushing an individual towards quitting. Raising pay levels may thus result in greater job satisfaction where people are already happy with their work, but it will not deter unhappy employees from leaving. Sturges and Guest (1999), in their study of leaving decisions in the field of graduate employment, summed up their findings as follows:

As far as they are concerned, while challenging work will compensate for pay, pay will never compensate for having to do boring, unstimulating work. (Sturges and Guest 1999, p. 19)

Recent research findings thus appear to confirm the views expressed by Herzberg (1966) that pay is a ‘hygiene factor’ rather than a motivator. This means that it can be a cause of dissatisfaction at work, but not of positive job satisfaction. People may be motivated to leave an employer who is perceived as paying badly, but once they are satisfied with their pay additional increases have little effect.

The other problem with the use of pay increases to retain staff is that it is an approach that is very easily matched by competitors. This is particularly true of ‘golden handcuff’ arrangements which seek to tie senior staff to an organisation for a number of years by paying substantial bonuses at a defined future date. As Cappelli (2000, p. 106) argues, in a buoyant job market, recruiters simply ‘unlock the handcuffs’ by offering equivalent signing-on bonuses to people they wish to employ.

It is important that employees do not perceive their employers to be treating them inequitably. Provided pay levels are not considerably lower than those paid by an organisation’s labour market competitors, other factors will usually be more important contributors towards high turnover levels. Where the salaries that are paid are already broadly competitive, little purpose is served by increasing them further. The organisation may well make itself more attractive in recruitment terms, but the effect on staff retention will be limited. Moreover, of course, wage costs will increase.

There is potentially more to be gained from enhancing benefits packages, because these are less easily imitated or matched by competitors. Where particular benefits, such as staff discounts, holiday entitlements or private healthcare schemes, are appreciated by staff, they are more likely to have a positive effect on staff turnover than simply paying higher base wages. Potentially the same is true of pension schemes, which are associated with relatively high levels of staff retention. However, the research evidence suggests that except for older employees who have completed many years of service, most pension schemes are not sufficiently valued by staff to cause them to stay in a job with which they are dissatisfied (Taylor 2000). Arguably, the best way of using benefits to keep a lid on staff turnover is to move towards flexible schemes such as those discussed in Chapter 29. An employer who allows individual employees to choose how they make up their own remuneration package will generally be more attractive than one who only offers a ‘one size fits all’ set of benefits.

While pay rates and benefit packages may play a relatively marginal role in the retention of good people, reward in the broader sense plays a more significant role. If employees do not find their work to be ‘rewarding’ in the broadest sense of the word, they will be much more likely to start looking for alternative jobs. Making work rewarding is a good deal harder for managers to achieve because different people find different aspects of their work to be rewarding. There is thus a need to understand what makes people tick and to manage them as individuals accordingly. Getting this right is difficult, but achieving it is worthwhile from the point of view of retaining people. It is far harder for would-be competitors to imitate the effective motivation of an individual than it is for them to increase the salary that a person is paid.

2.2. Managing expectations

For some years research evidence has strongly suggested that employers benefit from ensuring that potential employees gain a ‘realistic job preview’ before they take up a job offer. The purpose is to make sure that new staff enter an organisation with their eyes wide open and do not find that the job fails to meet their expectations. A major cause of job dissatisfaction, and hence of high staff turnover, is the experience of having one’s high hopes of new employment dashed by the realisation that it is not going to be as enjoyable or stimulating as anticipated.

Several researchers have drawn attention to the importance of these processes in reducing high turnover during the early months of employment (e.g. Wanous 1992, pp. 53-87; Hom and Griffeth 1995, pp. 193-203). The need is to strike a balance at the recruitment stage between sending out messages which are entirely positive and sending out those which are realistic. In other words, it is important not to mislead candidates about the nature of the work that they will be doing.

Realistic job previews are most important when candidates, for whatever reason, cannot know a great deal about the job for which they are applying. This may be because of limited past experience or it may because the job is relatively unusual and not based in a type of workplace with which job applicants are familiar. An example quoted by Carroll et al. (1999, p. 246) concerns work in nursing homes, which seems to attract people looking to undertake a caring role but who are unfamiliar with the less attractive hours, working conditions and job duties associated with the care assistant’s role. The realistic job preview is highly appropriate in such a situation as a means of avoiding recruiting people who subsequently leave within a few weeks.

The importance of unmet expectations as an explanation for staff turnover is also stressed by Sturges and Guest (1999, pp. 16 and 31) in their work on the retention of newly recruited graduates. Here the problem is one of employers overselling graduate careers when competing with others to secure the services of the brightest young people:

False impressions are given and a positive spin put on answers to questions so as to deter able applicants from taking up alternative offers. As a result, graduates start work confident in the belief that their days will be filled with interesting work, that they will be treated fairly and objectively in terms of performance assessment, that their career development will be fostered judiciously, and that their working lives will in some way be ‘fun’ and ‘exciting’. That is fine if it really can be guaranteed. Unfortunately such is often not the case, and unsurprisingly it leads to early dissatisfaction and higher turnover rates than are desirable. (Jenner and Taylor 2000, p. 155)

A solution, aside from the introduction of more honest recruitment literature, is to provide periods of work experience for students before they graduate. A summer spent working somewhere is the best possible way of finding out exactly what a particular job or workplace is really like. The same argument can be deployed in support of work experience for young people who are about to leave school in order to enter the job market.

2.3. Induction

Another process often credited with the reduction of turnover early in the employment relationship is the presence of effective and timely induction. It is very easy to overlook in the rush to get people into key posts quickly and it is often carried out badly, but it is essential if avoidable early turnover is to be kept to a minimum. Gregg and Wadsworth (1999, p. Ill) show in their analysis of 870,000 workers starting new jobs in 1992 that as many as 17 per cent had left within three months and 42 per cent within 12 months. No doubt a good number of these departures were due either to poorly managed expectations or to ineffective inductions.

Induction has a number of distinct purposes, all of which are concerned with preparing new employees to work as effectively as possible and as soon as is possible in their new jobs. First, it plays an important part in helping new starters to adjust emotionally to the new workplace. It gives an opportunity to ensure that they understand where things are, who to ask when unsure about what to do and how their role fits into the organisation generally. Second, induction provides a forum in which basic information about the organisation can be transmitted. This may include material about the organisation’s purpose, its mission statement and the key issues it faces. More generally a corporate induction provides a suitable occasion to talk about health and safety regulations, fire evacuation procedures and organisational policies concerning matters like the use of telephones for private purposes. Third, induction processes can be used to convey to new starters important cultural messages about what the organisation expects and what employees can expect in return. It thus potentially forms an important stage in the establishment of the psychological contract, leaving new employees clear about what they need to do to advance their own prospects in the organisation. All these matters will be picked up by new starters anyway in their first months of employment, but incorporating them into a formal induction programme ensures that they are brought up to speed a good deal more quickly, and that they are less likely to leave at an early date.

There is no ‘right’ length for an induction programme. In some jobs it can be accomplished effectively in a few days, for others there is a need for some form of input over a number of weeks. What is important is that individuals are properly introduced both to the organisation and to their particular role within it. These introductons are usually best handled by different people. Organisational induction, because it is given to all new starters, is normally handled centrally by the HR department and takes place in a single place over one or two days. Job-based induction takes longer, will be overseen by the individual’s own line manager and will usually involve shadowing colleagues. The former largely takes the form of a presentation, while the latter involves the use of a wider variety of training methods. IRS (2000c, pp. 10-12) draws attention to the recent development of web-based training packages which allow new employees to learn about their organisations and their jobs at their own pace, when they get the opportunity.

2.4. Family-friendly HR practices

Labour Force Survey statistics show that between 5 per cent and 10 per cent of employees leave their jobs for ‘family or personal reasons’ (IRS 1999, p. 6), while Hom and Griffeth (1995, p. 252) quote American research indicating that 33 per cent of women quit jobs to devote more time to their families – a response given by only one per cent of men. To these figures can be added those quoted by Gregg and Wadsworth (1999, 116) which show average job tenure among women with children in the UK to be over a year shorter than that of women without children and almost two years shorter than that of men. These statistics suggest that one of the more significant reasons for voluntary resignations from jobs is the inability to juggle the demands of a job with those of the family. They indicate that there is a good business case, particularly where staff retention is high on the agenda, for considering ways in which employment can be made more family friendly.

As a result of legislation under the Working Time Regulations 1998, the Employment Relations Act 1999, the Employment Act 2002 and the Work and Families Act 2006, UK employers are now obliged by law to provide the following as a minimum floor of rights:

- nine months’ leave for all employees paid according to a formula set out in the regulations;

- an additional three months’ unpaid maternity leave for employees;

- reasonable paid time off for pregnant employees to attend ante-natal clinics;

- specific health and safety measures for workers who are pregnant or have recently given birth;

- four weeks’ paid holiday each year in addition to eight bank holidays;

- a total of three months’ unpaid parental leave for mothers and fathers on the birth or adoption of a child;

- reasonable unpaid time off for employees to deal with family emergencies such as the sickness of a child or dependent relative;

- consideration of reasonable requests by parents of young children and with caring responsibilities for adults to work flexibly;

- two weeks’ paid paternity leave for new fathers.

Many employers, however, have decided to go a good deal further down this road than is required by law. The most common example is the provision of more paid maternity leave and the right, where possible, for mothers to return to work on a part-time or job-share basis if they so wish. Creche provision is common in larger workplaces, while others offer childcare vouchers instead. Career breaks are offered by many public sector employers, allowing people to take a few months off without pay and subsequently to return to a similar job with the same organisation. Flexitime systems such as those described in Chapter 6 are also useful to people with families and may thus serve as a retention tool in some cases. In the USA the literature indicates growing interest in ‘elder care’ arrangements (Lambert 2000) aimed specifically at providing assistance to those seeking to combine work with responsibility for the care of elderly relatives. An example in the UK is the ‘granny creche’ established by Peugeot for employees at its plant in Coventry. You can read much more about these and other work-life-balance initiatives in Chapter 31.

2.5. Training and development

There are two widely expressed, but wholly opposed, perspectives on the link between training interventions and employee turnover. On the one hand is the argument that training opportunities enhance commitment to an employer on the part of individual employees, making them less likely to leave voluntarily than they would if no training were offered. The alternative view holds that training makes people more employable and hence more likely to leave in order to develop their careers elsewhere. The view is thus put that money spent on training is money wasted because it ultimately benefits other employers.

Green et al. (2000, pp. 267-72) report research on perceptions of 1,539 employees on different kinds of training. They found that the overall effect is neutral, 19 per cent of employees saying that training was ‘more likely to make them actively look for another job’ and 18 per cent saying it was less likely to do so. However, they also found the type of training and the source of sponsorship to be a significant variable. Training which is paid for by the employer is a good deal less likely to raise job mobility than that paid for by the employee or the government. Firm-specific training is also shown in the study to be associated with lower turnover than training which leads to the acquisition of transferable skills. The point is made, however, that whatever the form of training, an employer can develop a workforce which is both ‘capable and committed’ by combining training interventions with other forms of retention initiative.

The most expensive types of training intervention involve long-term courses of study such as an MBA, CIPD or accountancy qualification. In financing such courses, employers are sending a very clear signal to the employees concerned that their contribution is valued and that they can look forward to substantial career advancement if they opt to stay. The fact that leaving will also mean an end to the funding for the course provides a more direct incentive to remain with the sponsoring employer.

2.6. Improving the quality of line management

If it is the case that many, if not most, voluntary resignations are explained by dissatisfaction on the part of employees with their supervisors, it follows that the most effective means of reducing staff turnover in organisations is to improve the performance of line managers. Too often, it appears, people are promoted into supervisory positions without adequate experience or training. Organisations seem to assume that their managers are capable supervisors, without recognising that the role is difficult and does not usually come naturally to people. Hence it is common to find managers who are ‘quick to critise but slow to praise’, who are too tied up in their own work to show an interest in their subordinates and who prefer to impose their own solutions without first taking account of their staff’s views. The solution is to take action on various fronts to improve the effectiveness of supervisors:

- select people for line management roles following an assessment of their supervisory capabilities;

- ensure that all newly appointed line managers are trained in the art of effective supervision;

- regularly appraise line managers on their supervisory skills.

This really amounts to little more than common sense, but such approaches are the exception to the rule in most UK organisations.

Source: Torrington Derek, Hall Laura, Taylor Stephen (2008), Human Resource Management, Ft Pr; 7th edition.

I like what you guys are up too. Such intelligent work and reporting! Keep up the excellent works guys I¦ve incorporated you guys to my blogroll. I think it’ll improve the value of my site 🙂

I’ve read some good stuff here. Certainly value bookmarking for revisiting. I surprise how much effort you put to create such a wonderful informative site.