A company’s choice of its entry mode for a given product/target country is the net result of several, often conflicting, forces. The variety of forces, difficulties in measuring their strength, and the need to anticipate their direction over a future planning period combine to make the entry mode decision a complex process with numerous trade-offs among alternative entry modes. To handle this complexity, managers need an analytical model that facilitates systematic comparisons among entry modes. This model is introduced in Chapter 6, after the reader has become familiar with the benefit/cost features of individual entry modes. For the present, we offer a general review of the external and internal factors that influence the choice of entry mode.

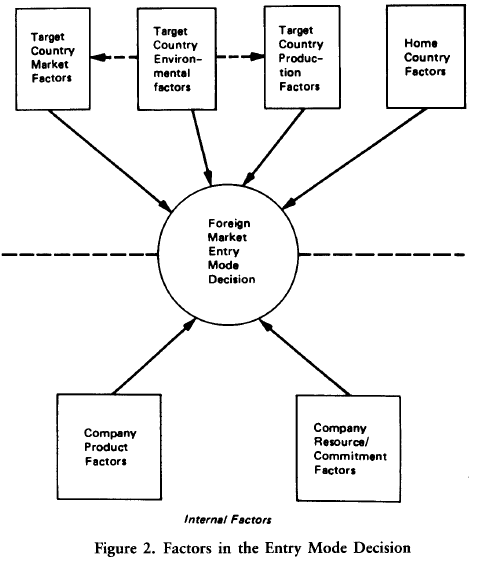

These factors are designated in Figure 2. The following comments are intended to be only suggestive of their influence.

1. External Factors

Market, production, and environmental factors in both the target and home countries can seldom be affected by management decisions. They are external to the company and may be regarded as parameters of the entry mode decision. Because no single external factor is likely to have a decisive influence on the entry mode for companies in general (although it may have for an individual company), we can only say that such factors encourage or discourage a particular entry mode.

Target Country Market Factors. The present and projected size of the target country market is an important influence on the entry mode. Small markets favor entry modes that have low breakeven sales volumes (indirect and agent/distributor exporting, licensing, and some contractual arrangements). Conversely, markets with high sales potentials can justify entry modes with high breakeven sales volumes (branch/ subsidiary exporting and equity investment in local production).

Another dimension of the target market is its competitive structure: markets can range from atomistic (many nondominant competitors) to oligopolistic (a few dominant competitors) to monopolistic (a single firm).

An atomistic market is usually more favorable to export entry than an oligopolistic or monopolistic market, which often requires entry via equity investment in production to enable the company to compete against the power of dominant firms. In target countries where competition is judged too strong for both export and equity modes, a company may turn to licensing or other contractual modes.

Another dimension of the target country market that deserves mention is the availability and quality of the local marketing infrastructure. For instance, when good local agents or distributors are tied to other firms or are simply nonexistent, an exporting company may decide that the market can be reached only through a branch/subsidiary entry mode.

Target Country Production Factors. The quality, quantity, and cost of raw materials, labor, energy, and other productive agents in the target country, as well as the quality and cost of the economic infrastructure (transportation, communications, port facilities, and similar considerations) have an evident bearing on entry mode decisions. Low production costs in the target country encourage some form of local production as against exporting. Obviously, high costs would militate against local manufacturing.

Target Country Environmental Factors. The political, economic, and sociocultural character of the target country can have a decisive influence on the choice of entry mode. Perhaps most noteworthy are government policies and regulations pertaining to international business. Restrictive import policies (high tariffs, tight quotas, and other barriers) obviously discourage an export entry mode in favor of other modes.1 The recent decision of several Japanese automobile companies to manufacture vehicles in the United States instead of exporting them from Japan is largely a response to actual and potential U.S. import restrictions. Similarly, a restrictive foreign investment policy generally discourages equity investment in favor of other primary modes, and may discourage sole ventures in favor of joint ventures or acquisitions in favor of new establishments. On the other hand, a target country may encourage foreign investment by offering such incentives as tax holidays.

Another environmental factor is geographical distance. When the distance is great, transportation costs can make it impossible for some export goods to compete against local goods in the target country. Thus high transportation costs discourage export entry in favor of other modes that do not incur such costs. When “knockdown” shipments substantially reduce transportation costs, it may be possible for an exporting company to compete by establishing an assembly operation in the target country, representing only a modest shift to an investment entry mode.

Many features of the target country’s economy can influence the choice of entry mode. The most fundamental feature is whether the economy is a market economy or a centrally planned socialist economy. Equity entry modes are usually not possible in the latter, so companies wanting to do business with socialist countries must rely on nonequity exporting, licensing, or other contractual modes.

Other features are the size of the economy (as measured by gross national product), its absolute level of performance (gross national product per capita), and the relative importance of its economic sectors (as a percentage of gross national product). Generally, these features relate closely to the market size for a company’s product in the target country.

Still another features pertain to the dynamics of the target country’s economy: the rate of investment, the growth rate of gross national product and personal income, changes in employment, and the like. Dynamic economies may justify entry modes with a high breakeven point even when the current market size is below the breakeven point.

International managers should also examine the target country’s external economic relations: the direction, composition, and value of exports and imports, the balance of payments, the debt service burden, exchange rate behavior, and so on. Substantial one-way changes in external economic relations are indicators of probable future changes in government policies on trade and international payments. For example, a persistent weakening of a country’s balance of payments commonly leads to import restrictions and/or payments restrictions (particularly in developing countries) and/or devaluation of the exchange rate. Each of these prospective changes will have a different influence on entry modes. Although import restrictions discourage export entry, exchange controls that limit the repatriation of income and capital tend to discourage equity entry more than other modes. When the exchange rate is allowed to depreciate, the effect is to discourage export entry and, at the same time, encourage equity investment entry. A case in point is the decision by Volkswagen in the mid-1970s to revise its entry mode by acquiring production facilities in the United States—the prolonged decline in the dollar relative to the deutsche mark made export entry unprofitable but, at the same time, made investment more profitable by lowering the deutschemark cost of acquisition and production in the United States.

Sociocultural factors also influence a company’s choice of entry mode. Of general significance is the cultural distance between the home country and target country societies. When the cultural values, language, social structure, and ways of life of the target country differ strikingly from those of the home country, international managers are more inclined to feel ignorant about the target country and fearful of their capacity to manage production operations there. Furthermore, great cultural distance usually makes for high costs of information acquisition. Thus a substantial cultural distance favors nonequity entry modes that limit a company’s commitment in the target country.

Cultural distance also influences the time sequence in the choice of target countries, because companies tend to enter first those foreign countries that are culturally close to the home country. For that reason (as well as because of physical proximity) Canada is a favorite first-entry country for equity investment by U.S. companies. Because managers are much more confident about their capacity to run operations in a target country that is culturally close to the home country, they are more willing to choose high- commitment entry modes than would otherwise be the case.

In closing this brief overview of environmental factors, we should mention the influence of political risk on entry modes, a subject treated in Chapter 5. When international managers perceive high political risks in a target country, such as general political instability or the threat of expropriation, they favor entry modes that limit the commitment of company resources. Conversely, low political risks encourage equity investment in a target country.

Empirical Verification of the Influence of External Factors. An empirical study supports our general statements on the influence of market, production, and environmental factors in the target country.2 Comparing 100 countries on the basis of 59 characteristics, this study grouped the countries into three clusters, which were designated “hot,” “moderate,” and “cold.” Hot countries were characterized by very stable governments, high market opportunity, advanced levels of economic development and performance, and low legal, physiographic, and geocultural barriers: West European countries, Canada, Australia, New Zealand, and Japan. Cold countries had the opposite characteristics (all the African countries except South Africa, most of the Middle East, most of Southeast Asia, plus India, Argentina, Bolivia, Haiti, Paraguay, Peru, and Greece). Moderate countries revealed characteristics that lay between those of the hot and cold countries (most of the Caribbean and Latin American countries as well as Finland, Hong Kong, Israel, Kuwait, Lebanon, Malaysia, Portugal, Ireland, Spain, South Korea, Taiwan, South Africa, and Yugoslavia).

The study next calculated for each country the frequency distribution of market entry modes of 250 U.S. manufacturers. The findings show that as companies move from hot to cold countries, they depend increasingly on export entry and decreasingly on investment in local production. For the average hot country, exporting represented 47.2 percent of all entry modes, investment in local production represented 28.5 percent, and licensing and mixed modes accounted for the remainder. In sharp contrast, for the average cold country, exporting represented 82.6 percent of all entry modes, investment in local production represented only 2.9 percent, and licensing and mixed modes took care of the remainder. The entry mode profile for the average moderate country lay between the profiles of the average hot and cold countries.

Home Country Factors. Market, production, and environmental factors in the home country also influence a company’s choice of entry mode to penetrate a target country. A big domestic market allows a company to grow to a large size before it turns to foreign markets. As we shall see later, when large companies go abroad, they are more inclined to use equity modes of entry than small companies. (Another effect of a large domestic market is to make companies more domestic-oriented and less interested in all forms of international business than firms in small-market countries.)

Conversely, companies in small-market countries are attracted to exporting as the way to reach optimum size with economies of scale.

The competitive structure of the home market also affects the entry mode. Firms in oligopolistic industries tend to imitate the actions of rival domestic firms that threaten to upset competitive equilibrium. Hence, when one firm invests abroad, rival firms commonly follow its lead.3 Because oligopolists are unlikely to view a rival’s exporting or licensing activities as a competitive threat, oligopolistic reaction is biased toward investment in production. Indeed, the bulk of U.S. investment abroad has been made by companies in oligopolistic industries. On the other hand, companies in atomistic industries are more inclined to enter foreign markets as exporters or licensors.

Two other home country factors deserve mention. High production costs in the home country relative to the foreign target country encourage entry modes involving local production, such as licensing, contract manufacture, and investment. The second factor is the policy of the home government toward exporting and foreign investment by domestic firms. When the home government offers tax and other incentives for exporting, but, at the same time, is neutral or even restrictive on foreign investment (a common situation), then its policy is biased in favor of exporting and licensing or other contractual modes of foreign market entry.

2. Internal Factors

How a company responds to external factors in choosing an entry mode depends on internal factors.

Product Factors. International product policies are taken up in Chapter 2. For the moment we are concerned only with how product factors influence the entry mode.

Highly differentiated products with distinct advantages over competitive products give sellers a significant degree of pricing discretion. Consequently, such products can absorb high unit transportation costs and high import duties and still remain competitive in a foreign target country. In contrast, weakly differentiated products must compete on a price basis in a target market, which may be possible only through some form of local production. Hence high product differentiation favors export entry, while low differentiation pushes a company toward local production (contract manufacture or equity investment). The great majority of U.S. exports of manufactures consists of highly differentiated products.

A product that requires an array of pre- and post-purchase services (as is true of many industrial products) makes it more difficult for a company to market the product at a distance. Ordinarily, the performance of product services demands proximity to customers. Thus service-intensive manufactured products are biased toward branch/subsidiary exporting and local production modes of entry.

This last point brings us to another. If a company’s product is itself a service, such as engineering, advertising, computer services, tourism, management consulting, banking, retailing, fast-food services, or construction, then the company must find a way to perform the service in the foreign target country, because services cannot be produced in one country for export to another. Local service production can be arranged by training local companies to provide the service (as in franchising), by setting up branches and subsidiaries (as an advertising agency or branch bank), or by directly selling the service under contract with the foreign customer (as in technical agreements and construction contracts).

Technologically intensive products give companies an option to license technology in the foreign target country rather than use alternative entry modes. Since technology intensity is generally higher for industrial products than for consumer products, industrial-products companies are more inclined to enter licensing arrangements than consumer-products companies. The latter can, of course, license their trademarks, but only after they have achieved an international reputation.

Products that require considerable adaptation to be marketed abroad favor entry modes that bring a company into close proximity with the foreign market (branch/subsidiary exporting) or into local production. The latter is indicated when adaptation would require new production facilities and/or the adapted product could not be sold in the domestic market. Until the 1980s, for example, Ford and General Motors manufactured vehicles in Europe that were fundamentally different from the vehicles they manufactured at home.

Resource/Commitment Factors. The more abundant a company’s resources in management, capital, technology, production skills, and marketing skills, the more numerous its entry mode options. Conversely, a company with limited resources is constrained to use entry modes that call for only a small resource commitment. Hence company size is frequently a critical factor in the choice of an entry mode.

Although resources are an influencing factor, they are not sufficient to explain a company’s choice of entry mode. Resources must be joined with a willingness to commit them to foreign market development. A high degree of commitment means that managers will select the entry mode for a target country from a wider range of alternative modes than managers with low commitment. Hence a high-commitment company, regardless of its size, is more likely to choose equity entry modes.

The degree of a company’s commitment to international business is revealed by the role accorded to foreign markets in corporate strategy, the status of the international organization, and the attitudes of managers. For most companies, international commitment has grown along with international experience over a lengthy period of time. Success in foreign markets has encouraged more international commitment, which in turn has led to more success. On the other hand, failure early in a company’s international experience can reverse or limit its commitment.

Table 2 summarizes the influence of external and internal factors on the choice of entry mode. It reaffirms our earlier statement that a company’s selection of its entry mode for a target/product country is the net result of several, often conflicting, forces.

Source: Root Franklin R. (1998), Entry Strategies for International Markets, Jossey-Bass; 2nd edition.

Some truly excellent articles on this site, regards for contribution.