The term ‘strategy’ goes back to Chandler, who defined strategy ‘as the determination of the basic longterm goals and objectives of an enterprise and the adoption of courses of action and allocation of resources necessary for carrying out these goals’ (Chandler 1962: 23). Consequently, strategic management is a set of managerial decisions and actions that determine the long-run performance of a firm. Therefore, strategic management emphasizes monitoring and evaluating of external opportunities and threats in light of an organization’s internal resource strengths and weaknesses. The strategy of a corporation involves a comprehensive master plan stating how the corporation will achieve its mission and objectives and maximize its competitive advantages (Wheelen & Hunger 2010). The concept of strategic management is focused primarily on the development of long-term corporate success. Strategies, due to external or internal circumstances, sometimes cannot be realized as planned. In this case, the strategy needs to be modified. Emergent and deliberate strategies create the firm’s realized strategy (Mintzberg, Lampel, Quinn, & Ghoshal 2003). Strategy indicates a complex bundle of planned activities for the attainment of long-term business objectives that also should consider emergent decision and action patterns. Optimal allocation of the firm’s entrepreneurial and management capabilities is of vital importance for effective strategy implementation (Kutschker & Schmid 2006).

Larger firms, such as multinational enterprises, usually follow three types of strategies that are hierarchically linked to the firm’s corporate level, strategic business unit (SBU) level, and functional (department) level. On the top management level (corporate level), there are directional strategies (where we should compete?) that can be categorized as growth, stability and retrenchment strategies. A growth strategy, as the term itself indicates, is launched in order to increase the firm’s turnover and profits through expansion. A stability strategy is implemented, for example, after the acquisition of another firm, so organizational integration of the acquired business activities is required. A retrenchment strategy is realized through the shutdown or outsourcing of businesses that continuously accumulate losses, and there is little hope that these poorly performing business units will recover in the future (Wheelen & Hunger 2010).

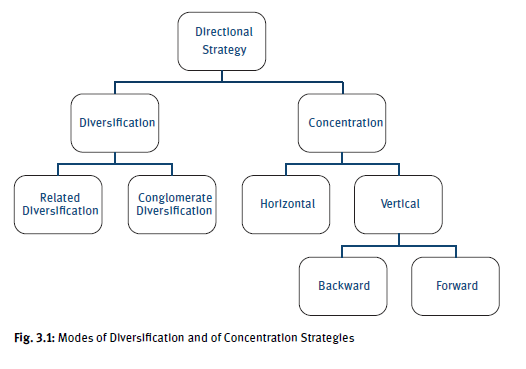

As illustrated in Figure 3.1, growth strategies are realized by expanding business activities in the current industry through enlargement of the current product portfolio or depth of value-adding activities. In this case we distinguish horizontal concentration (e.g., amplified range of the firm’s current products and services) and concentration strategy through vertical backward integration (taking over value-added activities previously done by the supplier) and vertical forward integration (moving ‘closer to the customer’ through one’s own sales branches). Concentration strategies are implemented by the management to focus on developing strategic core competencies, for example to gain technological leadership in a particular market. Concentration strategies are recommended when the management believes that the firm is doing business in markets which indicate attractive growth rates for the future. In case the firm’s management realizes (as a result of the environmental analysis, done for example with S. E. E. L. E. analysis methods) that the firm is not positioned in attractive and promising markets for the future, the management may decide to launch a diversification strategy. Diversification strategies are recommended to spread the firm’s business risk among separate and usually independent markets. In this case, new products and services are offered in related industries (related diversification – from the perspective of the firm’s current core business/current value adding activities) or in totally unrelated industries (conglomerate diversification – from the perspective of the firm’s current core business/current value adding activities). An example of conglomerate diversification is the carmaker Daimler AG which operates in the financing business through Mercedes-Benz Bank. Instead of manufacturing, Daimler has also recently entered the car-sharing business.

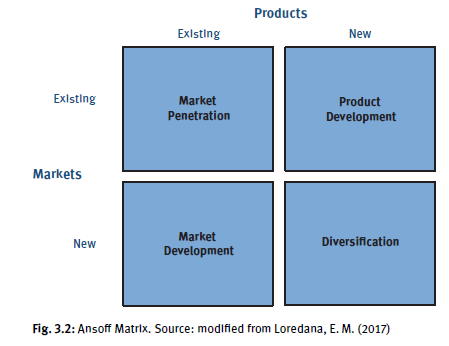

The ‘Ansoff product-market matrix’ categorizes four different strategic alternatives related to existing products and/or new products which are connected to business opportunities in existing and/or new markets (compare Figure 3.2). In case of market penetration, the management aims to increase its market share in existing markets with existing products and services. Market penetration can be reached, for example, through approaching competitors’ customers, gaining customers who did not buy the product before and intensifying the buying behavior of current firm customers through realizing higher purchase volumes (Loredana 2017; Schawel & Billing 2011). The second category – ‘product development’ – targets increasing demand in the existing market through the development of new or modified products (e.g., better matching specific customer requirements through products and services at different quality and price levels). In case of market development current firm products are offered in new markets (e.g., geographic business expansion). Diversification, according to the Ansoff matrix, is when new markets are entered with new products (Loredana 2017; Schawel & Billing 2011).

Porter’s concept of competitive strategies, named cost leadership, differentiation, and niche strategies, is realized in the firm’s strategic business units (SBUs). Competitive strategies (how we should compete?) follow up the top management’s decision on a directional strategic level (e.g., growth strategy through concentration or diversification). In case of cost leadership strategy the firm targets cost-efficient value-adding activities through economies of scale and experience curve effects, which are ideally combined with a high bargaining power of the firm. Cost leaders aim to learn ‘from the mistakes of the early moving firms.’ They are often found in rather mature markets which indicate high market volumes but intense price competition. Therefore cost leadership firms usually offer standardized products (Porter 1980; Porter & Kramer 2014). The opposite occurs in a differentiation strategy in which the management targets to differentiate the firm’s product and service from its competitors, for example through technological innovation, service, quality and sustainability. Therefore products and services are usually sold at higher levels than the average market price. Niche strategies combine both ‘cost aspects’ and ‘differentiation’ in rather smaller, separated markets. Porter has been criticized because of the nebulous line between ‘how much differentiation and how much cost awareness’ a firm’s management should take into consideration. Therefore, Porter further developed his concepts of generic (competitive) strategies and added ‘niche strategy with differentiation focus’ and ‘niche strategy with cost focus.’ Conceptual weaknesses still exist in terms of potential segmentation drawbacks concerning cost elements and differentiation elements (because the management needs to always consider both sides). Moreover the generic strategies are difficult to quantify and thus empirical verification is difficult. Despite conceptual weaknesses, there is no doubt: Porter’s generic strategies enjoy a high level of publicity, especially among business practitioners (Porter 1980; Porter & Kramer 2014).

At the final stage, after the directional strategy and the competitive strategy decisions have been made, the firm’s management needs to decide on the appropriate strategy mix on a functional (department) level. Functional strategy implements and realizes directional and business unit strategies by maximizing the firm’s department strengths and effectiveness (how we should implement what was decided on directional and competitive level before?). Functional strategies are concerned with developing a distinctive competence in order to provide the enterprise and its business units with a competitive advantage (Wheelen & Hunger 2010). For example, we distinguish purchasing strategies (e.g., single, parallel or multiple sourcing strategies), marketing strategies (e.g., penetration or skimming, push or pull strategies, shower or waterfall strategies), R&D strategies (technological leadership or followership strategy), and operations (e.g., individual order, serial or mass production). The firm gains competitive advantages when there is a strategic fit on all three levels (directional, competitive and functional). For example, a growth strategy through concentration and cost leadership necessarily requires a push strategy (communication), shower strategy (timing) and price penetration strategy in the marketing department, and technological followership in the research and development department, and so on.

In light of globalized integrated valued-added activities and international trade and capital flow patterns, a firm’s growth strategy is often realized through enlargement of its business by means of geographic expansion into foreign markets. As a result, the firm is engaged in internationalization processes because its products and services are transferred across national boundaries. The firm’s management selects the country and relevant actors; where or with whom the transaction should be performed; and the corresponding international exchange transaction modality, which is called a firm’s market entry strategy or, synonymously, market entry mode (Andersen & Buvik 2002). An entry mode refers to the institutional or organizational arrangement chosen by the firm for its business activities in target foreign markets (Hollensen, Boyd, & Ulrich 2011). The international business activity can range from manufacturing of goods, to servicing customers, to sourcing various inputs (Holtbrugge & Baron 2013; Welch, Benito, & Petersen 2007). When entering new markets, the operating management is confronted with various challenges that usually come along with more or less known societal, ecological, economic, legal/political, expertise (S. E. E. L. E.) and environmental surroundings. Thus, there should be various advantages from international business activities that cause firms to consider taking the risk of entering foreign markets. What motivates a firm to internationalize? The following are the main reasons

- Demand-oriented factors: Foreign market entry because of its attractiveness in terms of market volume and growth rates, which provide additional sales volumes, in addition to (often) saturated home markets.

- Supply-oriented factors: Access to rare and valuable resources found in foreign markets, such as qualified and motivated employees, raw materials, knowledge, technological expertise, infrastructure, and others.

- Follow-the-customer necessity: To avoid the risk of being dropped from the procurement list of an important customer, the supplier needs to follow its customer, which is engaged in a foreign target market.

- Follow-the-competitor necessity: To avoid leaving the competitors either with all the sales opportunities or all the investment benefits provided in a regional industry cluster in foreign markets, the firm must join the competitors in the foreign markets.

- Financial reasons: To realize the advantages of foreign markets because of investment incentives (tax reductions, subsidies), large multinationals can make use of cross-stock listing, less costly debt financing because of lower interest rates, and the higher liquidity of the foreign markets.

As is clear from the internationalization motives presented above, a firm does not always make its decision about whether, where, and how to internationalize independently but often makes the decision as a result of its bilateral relationships with other actors in its relevant industry network.

The strategic decision process in the course of entering foreign markets is relatively complex, and the outcomes of foreign business normally have a vital impact on a firm’s destiny. In other words, the decision regarding the foreign entry mode strategy is one of the most critical for the management. Among others, it is usually costly to change the mode of entry once it is established due to its long-term consequences for the firm (Brouthers & Hennart 2007; Pedersen, Petersen, & Benito 2002).

The choice of which foreign country to enter commits a firm to operating in a certain geographical and sociocultural terrain and signals its future strategic intention to customers, suppliers, competitors, and other stakeholders (Ellis 2000). The portfolio of international market entry strategies can basically be distinguished among contractual forms (e.g., exports, franchising, original equipment manufacturing); cooperative partnerships, such as international joint ventures; and foreign direct investments (e.g., wholly owned subsidiaries). These strategies will be explained in detail in the following sections of the chapter.

Source: Glowik Mario (2020), Market entry strategies: Internationalization theories, concepts and cases, De Gruyter Oldenbourg; 3rd edition.

Fantastic site. Plenty of helpful info here. I am sending it to a few buddies ans also sharing in delicious. And certainly, thank you to your effort!