1. Definition and Overview

Internal validity consists in being sure of the pertinence and internal coherence of the results produced by a study; researchers must ask to what degree their inferences are correct, and whether or not rival explanations are possible. They must assess, for example, whether variations of the variable that is to be explained are caused solely by the explanatory variables. Suppose that a researcher has established the causal relationship: ‘Variable A brings about the appearance of Variable B.’ Before asserting this conclusion, the researcher must ask himself or herself whether there are other factors causing the appearance of A and/or B, and whether the relationship established might not be rather of the type: ‘Variable X brings about the appearance of variables A and B.’

While internal validity is an essential test for research into causality, the concept can be extended to all research that uses inference to establish its results (Yin, 1989).

Testing internal validity is designed to evaluate the veracity of the connections established by researchers in their analyses.

There is no particular method of ensuring the ‘favourable’ level of internal validity of a research project. However, a number of techniques (which are more tests of validity in quantitative research and precautions to take in qualitative research) can be used to assess this internal validity.

2. Techniques for Assessing Internal Validity

We will not make any distinctions between techniques used for quantitative or qualitative research. Testing for internal validity applies to the research process, which poses similar problems regardless of the nature of the study.

The question of internal validity must be addressed from the stage of designing the research project, and must be pursued throughout the course of the study.

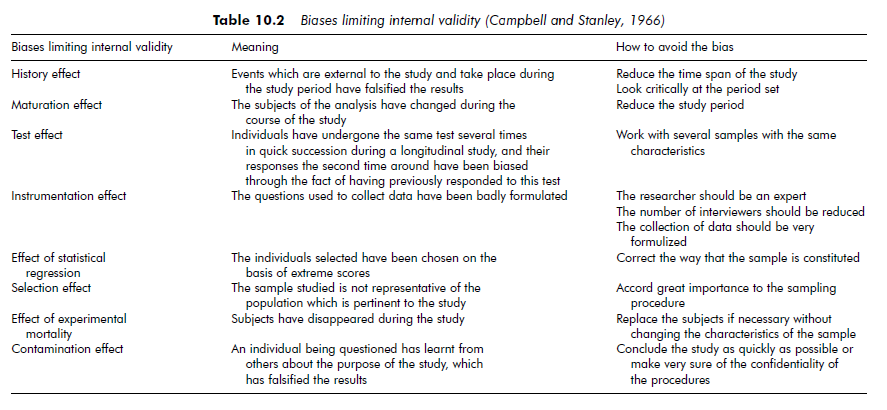

To achieve a good standard of internal validity in their research, researchers must work to remove the biases identified by Campbell and Stanley (1966). These biases (see Table 10.2) are relative: to the context of the research (the history effect, the development effect, the effect of testing); to the collection of data (the instrumentation effect); or to sampling (the statistical regression effect, the selection effect, the effect of experimental mortality, the contamination effect).

It is essential to anticipate, from the outset, effects that might be damaging to internal validity, and to design the research so as to limit the most serious of them.

Using a specific case study as an example, Yin (1989) presents a number of tactics to strengthen internal validity. These tactics can be extended to all qualitative research. He suggests that researchers should test rival hypotheses and compare the empirical patterns that are revealed with those of existing theoretical propositions. In this way, researchers can assess whether the relationship they establish between events is correct, and that no other explanation exists.

It is then necessary to describe and explain, in detail, the analysis strategy and the tools used in the analysis. Such careful explanation increases the transparency of the process through which results are developed, or at least makes this process available for criticism.

Finally, it is always recommended to try to saturate the observational field (to continue data collection until the data brings no new information and the marginal information collected does not cast any doubt on the construct design). A sufficiently large amount of data helps to ensure the soundness of the data collection process.

Miles and Huberman (1984a) reaffirm many of Yin’s suggestions, and propose a number of other tactics to strengthen internal validity. Researchers can, for example, examine the differences between obtained results and establish contrasts and comparisons between them: this is the method of ‘differences’. They can also verify the significance of any atypical cases – exceptions can generally be observed for every result. Such exceptions may either be ignored or the researcher may try to explain them, but taking them into account allows researchers to test and strengthen their results. Researchers can also test the explanations they propose. To do so, they will have to discard false relationships – that is, researchers should try to eliminate the possible appearance of any new factor which might modify the relationship established between two variables. Researcher can also test rival explanations that may account for the phenomenon being studied. Researchers rarely take the time to test any explanation other than the one they have arrived at. A final precaution is to seek out contradictory evidence. This technique involves actively seeking out factors that may invalidate the theory the researcher maintains as true. Once a researcher has established a preliminary conclusion, he or she must ask whether there is any evidence that contradicts this conclusion or is incompatible with it.

Source: Thietart Raymond-Alain et al. (2001), Doing Management Research: A Comprehensive Guide, SAGE Publications Ltd; 1 edition.

26 Jul 2021

26 Jul 2021

26 Jul 2021

26 Jul 2021

26 Jul 2021

26 Jul 2021