If a paper questionnaire is being used, the primary concern with regard to layout is that the interviewer can follow the questionnaire sequence easily, asking the correct questions for each respondent and accurately recording the answers. This is the case for both face-to-face and tele

phone interviews. If the interviewer has difficulty following the questionnaire or finding the correct question to ask, the flow of the interview can be lost, together with the interest and attention of the respondent. The wrong questions may be asked, which may be entirely inappropriate for the respondent and so lose the respondent’s confidence that the survey is worth the time taken to complete it. And, of course, relevant data will be lost.

Most research companies adopt a set of conventions and standardized templates for questionnaire layout that are designed to help the interviewer.

1. Font size and formats

It may be tempting to use a small font size in order to fit more questions on to each page. This is particularly the case with face-to-face interviews that are relatively long. It may be thought that response rates will be harmed if the potential respondent can see that the questionnaire is the size of a small book. In practice, this is not usually the case, however, and a crowded layout may just lead to interviewer error.

A questionnaire that is printed in a small-sized font will be difficult for interviewers to read. They are more likely to make mistakes both in determining which questions they are supposed to ask and in recording the responses accurately. The quality of the data therefore suffers. They are also more likely to lose respondents during the course of the interview if they make mistakes and ask inappropriate questions, or if there are long pauses between questions whilst the next question is found.

In any case, the likely length of the interview should be told to the respondent as accurately as possible at the outset, so the physical size of the questionnaire should not affect the respondent’s decision to cooperate.

It is usual to adopt a general font size of 10, 11 or 12 points, although of course larger font sizes can be used for key instructions.

Bold and italic formats can also be used to draw attention to instructions and key points, or to emphasize particular words in a question where that is necessary. It is important that formatting is used consistently (eg instructions to interviewers are always in bold and underlined; anything to be read aloud is in lower case) so that interviewers can distinguish clearly between instructions, directions, etc and what is to be read out.

A question should never be allowed to go over two pages, so causing interviewers to turn the page to see all of the possible responses. This is likely to lead to errors as the interviewers turn the pages backwards and forwards trying to match the respondents’ answers to the given precodes.

2. Upper and lower case

It is common to use upper and lower case to distinguish between questions that need to be read out and instructions for the interviewer that should not be. Most companies adopt the convention of upper case for instructions and lower case for items in the questionnaire that should be read out. This helps interviewers to distinguish quickly between instructions and questions and to see to whom they are meant to put a question and to whom they are not. Some agencies also embolden all instructions to help the interviewer to distinguish them. Others underline instructions for additional emphasis, or use selective underlining for important instructions.

This upper and lower case convention is often extended to the responses to pre-coded questions, which are given in upper case if they not to be read out and lower case if they are meant to be. Other agencies use lower case for all pre-coded responses. The former approach may distinguish better between what is and is not meant to be read out, so helping to avoid unintended prompting, while the latter may be easier and therefore faster for the interviewer to read and to code, so helping to maintain the flow of the interview.

3. Pre-coded responses

With pre-coded questions the responses are listed on the questionnaire. The order in which they are given can help (or hinder) the interviewer in finding the correct response code quickly. Usually, lists of brand names or simple categories would be given in alphabetical order. However, sometimes it is preferable to group them by categories or sub-categories, if that makes it quicker for the interviewer to find them.

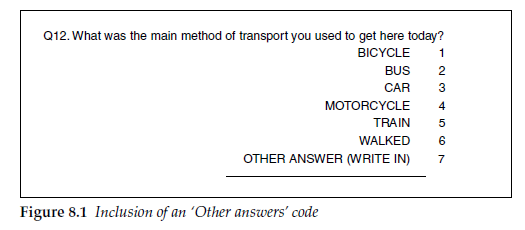

Note in Figure 8.1 the inclusion of an ‘Other answers’ code, together with an instruction that the interviewer should write in what that ‘other’ is. It is rare that the questionnaire writer can assume that all possible responses have been thought of and included in the pre-coded list. It is therefore generally prudent to allow for other answers to be given and recorded. Space should be left for the answer to be written in.

When there are a significant number of other answers, the researcher should look to see what they are. It may be that an important response has been overlooked or that there is an ambiguity in the response codes. A respondent to the question in Figure 8.1 may have travelled by tram. That this was not included in the pre-codes may have been an oversight because the researcher was unaware that the tram was an option, or it may have been that the researcher intended to include trams with buses, but failed to make this clear on the response list. If the missing response has been written in, the researcher has the option to create a new code for tram or to recode those who said tram into the bus category.

4. Single and multiple responses

Frequently it is clear from the question whether the anticipated response is a single answer or whether each respondent could give more than one. In the question about how the respondent travelled (Figure 8.1), the use of the term ‘main method of transport’ indicated to both respondent and interviewer that only one answer was expected.

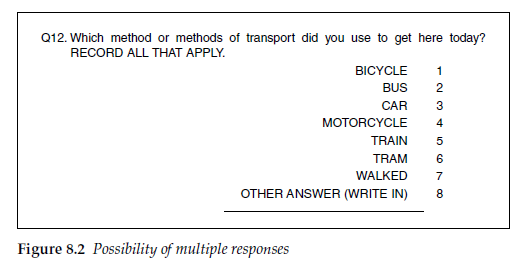

Had the question been asked as in Figure 8.2, more than one answer would have been possible. Now an instruction to accept multiple responses has been included to ensure that the interviewers recognize that this is permissible.

Wherever there is any possibility of ambiguity as to whether only one response or more than one is permissible, an instruction to the interviewer should be used to make it clear what is expected.

5. Common pre-code lists

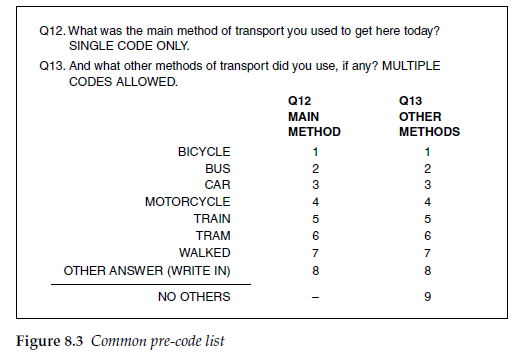

It often happens that successive questions use the same list of pre-codes. When that occurs a single set of responses can be used with the codes for each question next to each other, as in Figure 8.3. This arrangement saves space on the questionnaire, but also allows the interviewer to see what was coded for the first question and to ensure that the same answer is not coded for the second one. Clear instructions and headings are needed so that the interviewer can easily see to which question each column of code applies. Note the inclusion of a ‘No others’ response category for the second question.

6. ‘Don’t know’ responses

The example of the method of transport used does not include a ‘Don’t know’ category in the list of possible responses. In this instance that is justified because respondents are being interviewed shortly after arriving at the place of interview and it is reasonable to assume that they will remember how they travelled there.

However, had the question been about which brands of grocery products they had bought most recently, then a ‘Don’t know/Can’t remember’ category should have been included. It is not reasonable to assume that everybody will remember an event that may have taken place some time ago, particularly if it is an event that they see as being of little importance.

A fuller discussion of this is given in Chapter 4.

7. ‘Not answered’ codes

Some researchers argue that every question should include a ‘Not answered’ pre-code, so that, should it not be answered for any reason, there is a record that it has been asked. The argument against this is that having such a code could encourage interviewers to accept a refusal to reply too easily.

Occasionally respondents will refuse to answer or are unable to answer a question. If this occurs it is most likely to be because the question is sensitive in some way or because the response options are inadequate for the answer they wish to give. An example of the latter might be that the question asks for a single response but the answer given is a genuine multiple response. If the question asks which brand was most recently bought, but two different brands were bought at the same time, the interviewer or respondent may consider a multiple response as being contrary to instructions, and leave the question unanswered or coded ‘Don’t know’.

Where questions go unanswered, that is generally a shortcoming on the part of the questionnaire writer. Sensitive questions should be recognized as such and a ‘Refused’ category included on the list of pre-codes.

8. Show cards

Show cards are commonly used to prompt respondents with lists of possible responses. These can be lists of brands, time periods, behaviour, activities or attitude scales. It is important that interviewers show the correct card at the correct time. The most common practice is for cards to be identified by letters (Card A, Card B, etc) and for the instruction to show a particular card to appear at the appropriate question.

Sometimes the questionnaire writer wants to ensure that the card is removed from the respondent’s sight before subsequent questions are asked. This may occur when the card contains the description of a new product concept or an advertising idea and the researcher wants to establish which parts of it have stuck in the respondent’s mind. Then an instruction to remove the card from sight should be included.

9. Read-outs

Where an interviewer is to read out a number of response options, this should be clearly indicated as an instruction at the appropriate place.

Reading out is frequently used where respondents are asked to react to a list of attributes by associating them with brands, or to a list of attitude dimensions to which they indicate strength of agreement. The questionnaire writer should instruct interviewers as to whether or not the question should be repeated between each attribute or statement being read out. The initial question might be: ‘Which of these brands do you think is…? READ OUT.’ It may be unclear to interviewers whether they should read out that question at the front of each phrase, or whether it is only necessary to read it out once. If the questionnaire writer intends that it should be read out before each phrase, then this should be made clear.

10. Grids

Where a large grid is used to record responses, visual aids should be included in order to help the interviewer or respondent to record the responses correctly. A commonly used format is to have a number of brands across the top of the grid, which appear on a card shown to the respondent, and a list of attributes down the side of the grid that the interviewers read out. It can be difficult for interviewers to read across a large grid, and they may miscode an answer on to the wrong line, particularly when standing on a doorstep or in a mall.

Sight lines going across the page and shading of alternate lines are simple but effective ways of helping interviewers to avoid this type of error.

11. Routeing

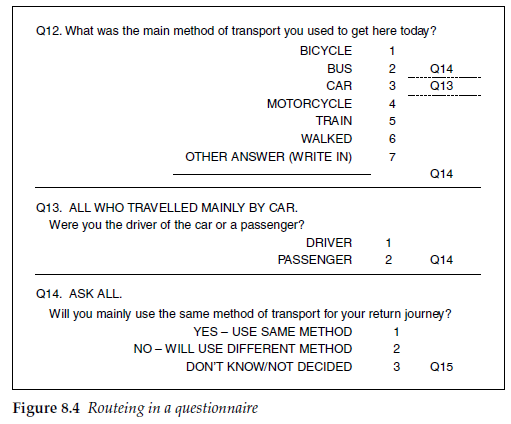

Clarity of routeing is one of the key aspects of an interviewer-administered paper questionnaire. If interviewers get lost in deciding which questions they should or should not be asking, the credibility of the survey is damaged in the eyes of the respondent and it is almost certain that questions will not be asked that should have been, so data will be lost.

Where routeing is dependent on the responses given to a question, the number of the subsequent question to be asked should be indicated alongside. In Figure 8.4, respondents who answered ‘car’ at Q12 are routed to Q13, whereas all others are routed to Q14. The heading at Q13 confirms to interviewers that this is the correct question to be asked of people who travelled mainly by car, and the heading at Q14 confirms that everybody should be asked this question.

Occasionally routeing can become very complex, with respondents coming to a question from a variety of routes, or with routes that are dependent upon the responses to more than one question. In these circumstances, the questionnaire writer should consider including the same question more than once in the questionnaire if doing so makes it less likely that routeing errors will be made.

12. Open-ended questions

Open-ended questions should be laid out with sufficient space for full responses to be written in. Interviewers will often stop probing once they have filled the space available to record the answer. More space can mean fuller responses.

Responses to open-ended questions will be coded into a number of categories depending on what answers are given and what answers are being looked for. The practices for recording these codes for data entry vary. Some companies leave a blank space for the coder to write in the appropriate code for the data enterer to use. Others print the codes on the questionnaire and the coder then circles the appropriate code in the same way as the interviewer records responses.

13. Thanking and classification questions

Interviewers rarely need reminding to thank respondents for their time and cooperation, especially if they have built up a rapport with them. However, it is good practice to include a line on the questionnaire thanking respondents for their time. It demonstrates that the questionnaire writer is also grateful to respondents for their help.

It is the practice in some research companies to record all classification details on the front page of the questionnaire even though they may not be asked until the end of the interview. This is to facilitate the checking of quota controls and demographic details when the questionnaire is returned to the office. If this is the case, it is prudent to include a reminder at the end of the questionnaire for the interviewer to return to the front page and complete the classification questions. Again, few interviewers will need reminding, but it is an indication of the questionnaire writer’s concern to help them if it is included.

14. Administrative information

Each study will require an identification code if you are carrying out, or are likely to carry out, more than one similar study. Each questionnaire will require a unique identifier or serial number so as to be able to distinguish between respondents. Interviewer-administered questionnaires should also include an interviewer identification code. Interviews can then be analysed by interviewer in order to determine any between-inter- viewer effects, or to identify interviewers who may have made errors in their interviews.

If there is more than one version of the questionnaire, the different versions will also usually need to be identified for analysis purposes.

15. Data entry

The format and layout for data entry will depend on the way in which the data are to be entered and the program that will be used to analyse them. The examples in this book generally use the column format. This has one or more columns allocated to each question, depending on the number of response codes required. Each column has 12 positions (1 to 9, 0, X, V), one of which is allocated to each response code. This is the format used by analysis programs such as those from Pulse Train and SPSS MR. Other programs use different formats.

If data are to be scanned in, using optical mark reading, there will be specific instructions regarding the layout, depending on the type of scanning equipment used. This usually involves having fixed points on each page from which the position of the marks made by the interviewer or respondent is measured. In Figures 8.5 and 8.6 the fixed marks are the diamonds in the four corners of the page. Note that the job identification and page numbers must also be included on each page in order to identify the scanned data correctly.

Source: Brace Ian (2018), Questionnaire Design: How to Plan, Structure and Write Survey Material for Effective Market Research, Kogan Page; 4th edition.

20 Aug 2021

20 Aug 2021

20 Aug 2021

20 Aug 2021

20 Aug 2021

20 Aug 2021