A job in an organization is a unit of work that a single employee is responsible for perform- ing. A job could include writing tickets for parking violators in New York City, performing MRIs at Salt Lake Regional Medical Center, reading meters for Pacific Gas and Electric, or doing long-range planning for The WB Television Network. Jobs are an important consideration for motivation because performing their components may provide rewards that meet employees’ needs. An assembly-line worker may install the same bolt over and over, whereas an emergency room physician may provide each trauma victim with a unique treatment package. Managers need to know what aspects of a job provide motivation as well as how to compensate for routine tasks that have little inherent satisfaction. Job design is the application of motivational theories to the structure of work for improving productivity and satisfaction. Approaches to job design are generally classified as job sim-plification, job rotation, job enlargement, and job enrichment.

1. JOB SIMPLIFICATION

Job simplification pursues task efficiency by reducing the number of tasks one person must do. Job simplification is based on principles drawn from scientific management and industrial engineering. Tasks are designed to be simple, repetitive, and standardized. As complexity is stripped from a job, the worker has more time to concentrate on doing more of the same routine task. Workers with low skill levels can perform the job, and the organi- zation achieves a high level of efficiency. Indeed, workers are interchangeable because they need little training or skill and exercise little judgment. As a motivational technique, how-ever, job simplification has failed. People dislike routine and boring jobs and react in a number of negative ways, including sabotage, absenteeism, and unionization.

2. JOB ROTATION

Job rotation systematically moves employees from one job to another, thereby increasing the number of different tasks an employee performs without increasing the complexity of any one job. For example, an autoworker might install windshields one week and front bumpers the next. Job rotation still takes advantage of engineering efficiencies, but it pro- vides variety and stimulation for employees. Although employees might find the new job interesting at first, the novelty soon wears off as the repetitive work is mastered.

Companies such as The Home Depot, Motorola, 1-800-Flowers, and Dayton Hudson have built on the notion of job rotation to train a flexible workforce. As companies break away from ossified job categories, workers can perform several jobs, thereby reducing labor costs and giving people opportunities to develop new skills. At The Home Depot, for ex- ample, workers scattered throughout the company’s vast chain of stores can get a taste of the corporate climate by working at in-store support centers, while associate managers can dirty their hands out on the sales floor.49 Job rotation also gives companies greater flexibility. One production worker might shift among the jobs of drill operator, punch operator, and assem- bler, depending on the company’s need at the moment. Some unions have resisted the idea, but many now go along, realizing that it helps the company be more competitive.50

3. JOB ENLARGEMENT

Job enlargement combines a series of tasks into one new, broader job. This type of design is a response to the dissatisfaction of employees with oversimplified jobs. Instead of only one job, an employee may be responsible for three or four and will have more time to do them. Job enlargement provides job variety and a greater challenge for employees. At May- tag, jobs were enlarged when work was redesigned so that workers assembled an entire water pump rather than doing each part as it reached them on the assembly line. Similarly, rather than just changing the oil at a Precision Tune location, a mechanic changes the oil, greases the car, airs the tires, and checks fluid levels, battery, air filter, and so forth. Then, the same employee is responsible for consulting with the customer about routine maintenance or any problems he or she sees with the vehicle.

4. JOB ENRICHMENT

Recall the discussion of Maslow’s need hierarchy and Herzberg’s two- factor theory. Rather than just changing the number and frequency of tasks a worker performs, job enrichment incorporates high-level motivators into the work, including job responsibility, recognition, and opportunities for growth, learning, and achievement. In an enriched job, employees have control over the resources necessary for performing it, make decisions on how to do the work, experience personal growth, and set their own work pace. Research shows that when jobs are designed to be controlled more by employees than by managers, people typically feel a greater sense of involvement, commitment, and motivation, which in turn contributes to higher morale, lower turnover, and stronger organi- zational performance.51

Many companies have undertaken job enrichment programs to increase employees’ involvement, motivation, and job satisfaction. At Ralcorp’s cereal manufacturing plant in Sparks, Nevada, for example, managers enriched jobs by combining several packing positions into a single job and cross-training employees to operate all of the packing line’s equipment. In addition, assembly-line employees screen, interview, and train all new hires. They are responsible for managing the production flow to and from their upstream and downstream partners, making daily decisions that affect their work, managing quality, and contributing to continuous improvement. Enriched jobs have improved employee motivation and satisfaction, and the company has benefited from higher long-term productivity, reduced costs, and happier, more motivated employees.52

5. JOB CHARACTERISTICS MODEL

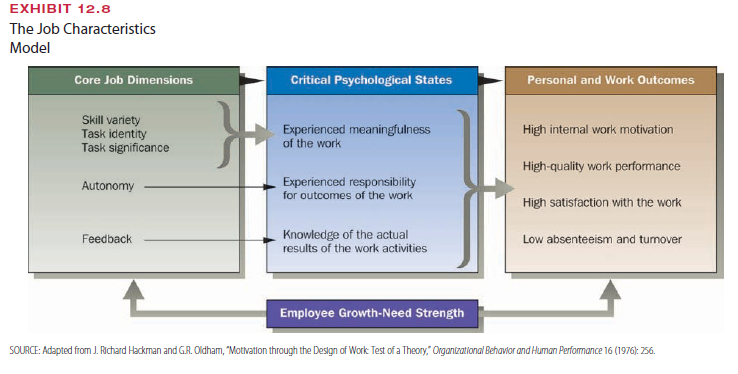

One significant approach to job design is the job characteristics model developed by Richard Hackman and Greg Oldham.53 Hackman and Oldham’s research concerned work redesign, which is defined as altering jobs to increase both the quality of employees’ work experience and their productivity. Hackman and Oldham’s research into the design of hundreds of jobs yielded the job characteristics model, which is illustrated in Exhibit 12.8. The model consists of three major parts: core job dimensions, critical psycho- logical states, and employee growth-need strength.

Core Job Dimensions. Hackman and Oldham identified five dimensions that determine a job’s motivational potential:

- Skill variety. The number of diverse activities that compose a job and the number of skills used to perform it. A routine, repetitious assembly-line job is low in variety, whereas an applied research position that entails working on new problems every day is high in

- Task identity. The degree to which an employee performs a total job with a recognizable beginning and ending. A chef who prepares an entire meal has more task identity than a worker on a cafeteria line who ladles mashed potatoes.

- Task significance. The degree to which the job is perceived as important and having im- pact on the company or consumers. People who distribute penicillin and other medical supplies during times of emergencies would feel they have significant jobs.

- Autonomy. The degree to which the worker has freedom, discretion, and self-determination in planning and carrying out tasks. A house painter can determine how to paint the house; a paint sprayer on an assembly line has little autonomy.

- Feedback. The extent to which doing the job provides information back to the employee about his or her performance. Jobs vary in their ability to let workers see the outcomes of their efforts. A football coach knows whether the team won or lost, but a basic research scientist may have to wait years to learn whether a research project was successful.

The job characteristics model says that the more these five core characteristics can be designed into the job, the more the employees will be motivated and the higher will be performance, quality, and satisfaction.

Critical Psychological States. The model posits that core job dimensions are more rewarding when individuals experience three psychological states in response to job design. In Exhibit 12.8, skill variety, task identity, and task significance tend to influ- ence the employee’s psychological state of experienced meaningfulness of work. The work it- self is satisfying and provides intrinsic rewards for the worker. The job characteristic of autonomy influences the worker’s experienced responsibility. The job characteristic of feed- back provides the worker with knowledge of actual results. The employee thus knows how he or she is doing and can change work performance to increase desired outcomes.

Personal and Work Outcomes. The impact of the five job characteristics on the psychological states of experienced meaningfulness, responsibility, and knowledge of actual results leads to the personal and work outcomes of high work motivation, high work performance, high satisfaction, and low absenteeism and turnover.

Employee Growth-Need Strength. The final component of the job char- acteristics model is called employee growth-need strength, which means that people have dif- ferent needs for growth and development. If a person wants to satisfy low-level needs, such as safety and belongingness, the job characteristics model has less effect. When a person has a high need for growth and development, including the desire for personal challenge, achievement, and challenging work, the model is especially effective. People with a high need to grow and expand their abilities respond favorably to the application of the model and to improvements in core job dimensions.

One interesting finding concerns the cross-cultural differences in the impact of job char- acteristics. Intrinsic factors such as autonomy, challenge, achievement, and recognition can be highly motivating in countries such as the United States. However, they may contribute little to motivation and satisfaction in a country such as Nigeria, and might even lead to demotivation. A recent study indicates that the link between intrinsic characteristics and job motivation and satisfaction is weaker in economically disadvantaged countries with poor gov- ernmental social welfare systems, and in high power distance countries, as defined in Chapter 3.54 Thus, the job characteristics model is expected to be less effective in these countries.

Source: Daft Richard L., Marcic Dorothy (2009), Understanding Management, South-Western College Pub; 8th edition.

Thank you for sharing with us, I conceive this website genuinely stands out : D.