We will start this section with a set of rules as checkpoints applicable to standard-form categorical syllogism. In a valid syllogism,

- There should be only three terms (each used consistently).

- The middle term should be distributed in at least one premise.

- The terms in the conclusion should be distributed in the premises.

- Both premises should not be negative.

- If one of the premises is negative, the conclusion should be negative.

- If both the premises are universal, the conclusion should be universal as well.

The above rules control the so-called standard syllogisms. Arguments as presented by researchers, even in the form of formal reports such as Ph.D. theses or journal publications, even those in scientific subjects (perhaps with the exception of mathematics and logic), seldom contain standard syllogisms. On the contrary, such reports are mostly formed with ordinary language. The reasons for this are understandable; ordinary language is more flexible, more resourceful, more interesting, and easier to use. But these attractions, themselves, may often lead the researcher away from the needed formality for correct thinking, resulting in botched arguments. The solution to such problems consists in translating the statements in ordinary language into the form of premises and conclusions and to arrange these, when possible, in the form of syllogisms, then to check their validity. Some of the problems in ordinary language and some of the possible solutions are briefly mentioned below in the form of examples.

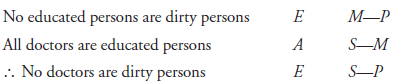

Example 1: Educated persons do not live filthy; all doctors are educated, so we may expect no physician to be dirty.

The above passage is close to, but not quite, a syllogism. Some modifications are necessary to reduce it to a standard syllogism. It can be noticed that the words “doctors” and “physicians” are used synonymously; “live filthy” and “dirty” are also used synony-mously; these inconsistencies in the use of terms should be rectified. With other minor changes, we may write the statement as

This is a standard EAE-1 valid syllogism.

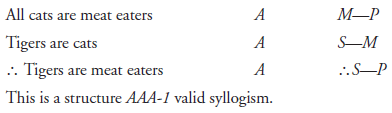

Example 2: All cats are meat eaters. A tiger, being a cat, eats meat.

Each of the premises in a standard syllogism should relate two classes and so should the conclusion. To reduce the above passage to standard form, “a cat” should be translated to the class of “cats”; and “eats meat” should be replaced from its present predicate form to a term designating the class of “meat eaters.” With these necessary changes, the passage can be translated as

Example 3: Where there is smoke, there is fire. Finding no smoke here, we may not find any fire.

A legitimate syllogism can be formed even with singular things, instead of with classes. Such syllogisms are not of standard form. When an exactly similar term is made to repeat in all the three propositions of the syllogism, the reduction is known as uniform translation. The above passage may be reduced with such translation to

All places where there is fire are places where there is smoke: A

This place is not a place where there is smoke: E

This place is not a place where there is fire: E

This is a syllogism with AEE mood with indefinite figure.

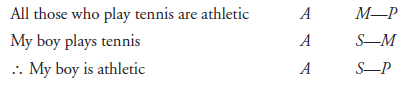

Example 4: My boy plays tennis. That is how he is athletic.

In this passage, the proposition that the boy is athletic is clearly the conclusion, but it is based on only one premise: that the boy plays tennis. Another premise, that “all those who play tennis are athletic,” is missing. This is typical of an argument that is stated incompletely, the unstated part being assumed to be so evident that it is superfluous. Ordinary language is replete with such arguments. In logic, they are said to be enthymematic, and the argument is referred as an enthymeme. To check the validity of the argument, it is thus necessary to state the suppressed proposition and complete the syllogism. When the major premise is the one that is left unexpressed, the enthymeme is said to be one of the first order; when the minor premise is suppressed, it is of the second order; when the conclusion itself is suppressed, it is of the third order. To reduce the above statement to a syllogism, we need to supply the major premise and translate as

This makes it a structure AAA-1 valid syllogism.

Example 5: Rama was either coronated as the future king or he was banished to the forest. He was not coronated as the future king; he was banished to the forest instead.

Disjunction is a condition of “either . . . or,” not both. Between two alternatives, strictly as stated, if one is yes, the other is no. The above statement may be reduced to a standard-form syllogism as follows:

Either Rama was coronated as the future king, or Rama was banished to the forest.

Rama was not coronated as the future king.

Rama was banished to the forest.

The above is referred to as a disjunctive syllogism.

Example 6: If there is rebirth, someone should have the experience of past birth. Since no one has such experiences, there cannot be rebirth.

This statement is of the form: “if. . . then’; thus, it is a hypothesis. The above statement can be translated as follows into a form known as a hypothetical syllogism:

If there is rebirth, then someone should have the experience of past birth.

No one has the experience of past birth.

There is no rebirth.

Example 7: If children are responsible, parental discipline is unnecessary, whereas if children are irresponsible, parental discipline is useless. Children are either responsible or irresponsible. Therefore, parental discipline is either unnecessary or useless.

The above statement is aptly called a dilemma. Such arguments advanced by researchers may appear logical. That it is not so can be realized by comparing the dilemma with a counterdilemma as follows:

If children are responsible, parental discipline is well received and useful; whereas, if children are irresponsible, parental discipline is necessary to correct them. Children are either responsible or irresponsible. Therefore, parental discipline is either useful or necessary.

It should be noticed that in both the original dilemma and the counterdilemma, the fact that children are neither totally responsible nor totally irresponsible is suppressed. Dilemmas are known to sway an uncritical audience and, so, may serve well in political (and religious) propaganda. But the researcher, bound by logic, should learn to shun dilemmas.

Source: Srinagesh K (2005), The Principles of Experimental Research, Butterworth-Heinemann; 1st edition.

5 Aug 2021

5 Aug 2021

5 Aug 2021

4 Aug 2021

5 Aug 2021

5 Aug 2021