A categorical syllogism is a deductive argument. As mentioned earlier, it consists of three categorical propositions, the first two of these, in sequence, being premises and the third, the conclusion. The term that occurs as the predicate of the conclusion is called the major term; the premise that contains the major term is known as the major premise. The term that occurs as the subject of the conclusion is called the minor term; the premise that contains the minor term is known as the minor premise. For instance, the following is a typical categorical syllogism:

All glasses are ceramic (first premise)

Pyrex is a glass (second premise)

Pyrex is a ceramic (conclusion)

Here, “ceramic” is the major term; “All glasses are ceramics” is the major premise; “Pyrex” is the minor term; and “Pyrex is a glass” is the minor premise. The third term of the syllogism, “glass,” which does not occur in the conclusion, is referred to as the middle term. Each of the propositions that constitute a given categorical syllogism is in any one of the four standard forms: A, E, I, and O.

1. Structures of Syllogisms

To be able to describe completely the structure (not the objects of the subject and predicate terms) of a given syllogism, we need to know its two descriptive components: (1) mood, and (2) figure.

The mood of a syllogism is determined by the forms of the three prepositions, expressed respectively in the order: the major premise, the minor premise, and the conclusion.

Example:

No saints are landowners: E

Some gurus are landowners: I

:. Some gurus are not saints: O

The mood of the above syllogism is EIO.

Knowing that there are only four forms of standard syllogisms, how many moods are possible? “The first premise may have any of the forms A, E, I, O; for each of these four possibilities, the second premise may also have any of the four forms; and for each of these sixteen possibilities, the conclusion may have any one of the four forms; which yields sixty-four moods.”

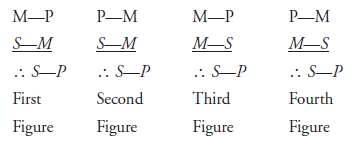

The descriptive component, the figure, on the other hand, makes reference to the two position of the middle term within a given syllogism. Symbolizing the major term by P, the minor term by S, we may think of the following four arrangements. In each the first line is the major premise, the second line is the minor premise and the third the conclusion. In each arrangement, each a variety of syllogisms, the positions of the two M’s determine the figure of that syllogism, referred to with an ordinal number as shown below.

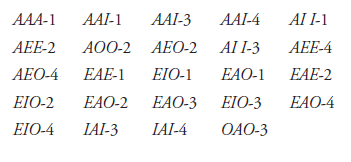

As indicated above, the four arrangements of the placement of the middle terms are respectively known as the first, second, third, and fourth figures. The syllogism used in the example above, it may be noted, is one of the second figure. Combining the mood and the figure, the structure of the above syllogism can be described as EIO-2. With sixty-four variations for mood, each with four variations for figure, 256 (64 x 4) distinct structures are possible, out of which, there are only twenty-four instruments of valid argument.

2. Validity of Syllogisms

The structure of a given syllogism determines the validity of the argument. And, the validity of an argument is independent of the content or subject matter therein, meaning, a valid argument does not necessarily yield a true conclusion.

For example, the following syllogism is a valid argument with form AAA-1, but its conclusion is wrong (that is, untrue), originating from the first false premise:

All animals are meat eaters: A

Cows are animals: A

Cows are meat eaters: A

This serves as an example for the principle that a wrong premise yields a wrong conclusion. If the premises are true, the conclusion from the above form of syllogism will come out true. For instance, the following syllogisms are both of the same form as before and yield true conclusions because each premise in both syllogisms is true.

All metals are electrical conductors.

Iron is a metal.

Iron is an electrical conductor.

and

All fungi are plants.

Mushrooms are fungi.

Mushrooms are plants.

These second and third instances of syllogisms of the form AAA-1 show a way of testing for the validity of a given syllogism.

Generalizing, we may state that a valid syllogism is valid by virtue of its structure alone. This means that if a given syllogism is valid, any other syllogism of the same structure will be valid also. Extending this, we may also say that if a given syllogism is invalid (or fallacious), any other syllogism of the same structure will be invalid (or fallacious) as well.

Applying this in practice amounts to this: any fallacious argument can be proved to be so by constructing another argument having exactly the same structure with premises that are known to be true and observing that the conclusion is known to be false. This situation generates an uneasy feeling that there ought to be a more formal and surer way to test the validity of syllogistic arguments. One such way is the pictorial (hence, formal) presentation of syllogisms, known as Venn diagrams.

3. Venn Diagrams for Testing Syllogisms

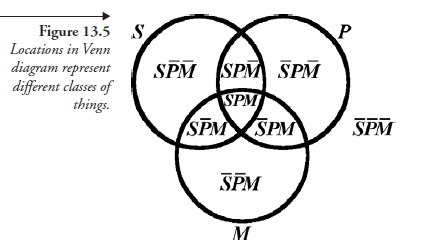

Categorical propositions having two terms, a subject and a predicate, require, as we have seen, two overlapping circles to symbolize their relation as Venn diagrams. Categorical syllogisms, on the other hand, having three terms, a subject, predicate, and middle term, require three overlapping circles to symbolize their relation as Venn diagrams. Conventionally, the subject and the predicate terms are represented by two overlapping circles in that order on the same line, and the middle term is represented by a third circle below and overlapping the other two. This arrangement divides the plane into eight areas as shown in Figure 13.5.

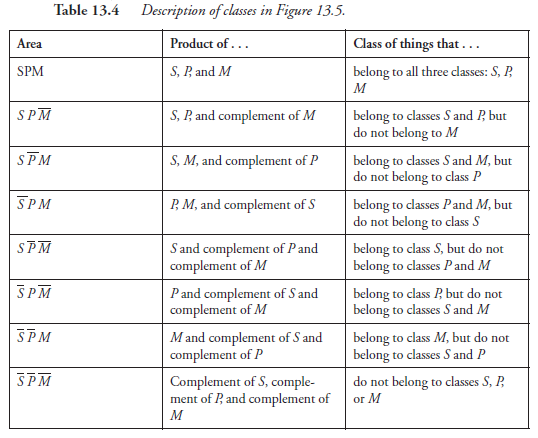

Table 13.4 shows the interpretation of these areas.

These class combinations light up with meanings when we assign S, P, and M to concrete things. For instance, suppose

- S is the class of all students.

- P is the class of all students studying physics.

- M is the class of all students studying mathematics.

Then, SPM is the class of students who study both physics and mathematics; S P M is the class of students who study mathematics but not physics; S PM is the class of students who study neither physics nor mathematics; and so on.

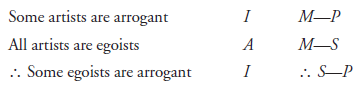

Further, among S, P, and M, it is possible to construct syllogisms of various moods and figures. For instance,

The given syllogism is of the structure IAI-3. It now remains to show how a Venn diagram helps us to determine if the above syllogism is or is not valid. The required procedure consists, in sequence, of the following five steps:

- Identify the names of the S, P, and M terms of the given syllogism.

- Draw the three-circle Venn diagram (as explained earlier), and label each circle with the right name.

- Check if one of the premises, major or minor, is universal, and the other particular.

4a. If the answer to (3) is yes, interpret the universal premise first, using two of the three circles of the Venn diagram as required. Then, superimpose the interpretation of the particular premise, using the required two circles for the purpose.

4b. If both the premises are universal, perform the procedure in (4a), with this difference: interpret the first universal premise first, and then superimpose the interpretation of the second universal premise (in the order stated) on the Venn diagram.

- Inspect the Venn diagram in terms of the conventional zone markings that resulted from the interpretation of the two premises, now having used all the three circles therein. There is no need to diagram the conclusion. Instead, check if the interpretation of the conclusion, in terms of zone markings, is now contained in the Venn diagram.

If it is, the categorical syllogism, as stated, is valid; if not, it is invalid.

Conforming to the above five numbered steps, we will interpret with Venn diagrams, two categorical propositions.

Example 1:

Categorical proposition stated above.

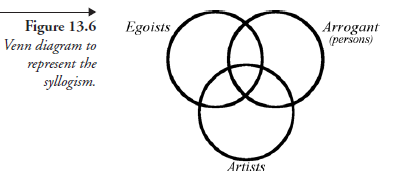

- S: Egoists

P: Arrogant (persons)

M: Artists

- Figure 13.6 is the three circle Venn diagram representing the syllogism.

- Only the second premise is universal.

4a. The circle representing the second premise is shaded as in Figure 13.7.

- Interpreting the conclusion requires that the area of intersection of the two circles “Egoists” and “Arrogant (persons)” contain some members. The zone on the right side of line marked “x” is such an area. Hence, the categorical syllogism, which has the form IAI-3, as stated, is valid, and valid are all categorical proposition of that form.

Example 2:

No professors are athletes: E P—M

All athletes are fun-mongers: A M—S

:. No fun-mongers are professors: E S—P

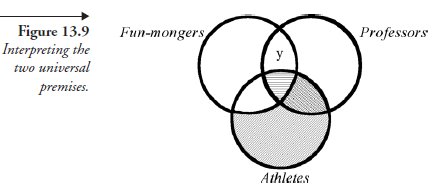

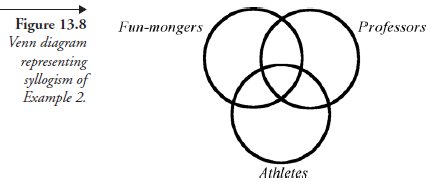

- S: Fun-mongers P: Professors M: Athletes

- Figure 13.8 is the three circle Venn diagram representing the syllogism of Example 2.

- The first and second premises are both universal.

- Performing the procedure of step 4G results in the Venn diagram shaded as in Figure 13.9.

- Interpreting the conclusion, as stated, requires that the area of intersection of the two circles “ Fun- mongers” and “ Professors” should be shaded (cross-hatched). What we have, instead, is clear area, markedy. Hence, the categorical proposition, which has the structure EAE-4, is invalid, as are all categorical syllogisms of that structure

.

.

Now, not incidentally, we have also used another criterion, besides Venn diagrams, to determine the validity of a given syllogism; it is the structure of the syllogism. Using Venn diagrams, we found that syllogisms of the structure IAI-3 are valid and that those of the structure EAE-4 are invalid. We pointed out earlier that there are 256 structures, in all, out of which only twenty- four are valid. All the others are known to be invalid. If we have the list of those that are valid, we need only evaluate a given syllogism to find its structure, then check whether it is one of those on the list. If it is, it is valid; if not, it is invalid. Given below is the complete list of those that are valid.

Source: Srinagesh K (2005), The Principles of Experimental Research, Butterworth-Heinemann; 1st edition.

5 Aug 2021

5 Aug 2021

5 Aug 2021

5 Aug 2021

5 Aug 2021

5 Aug 2021