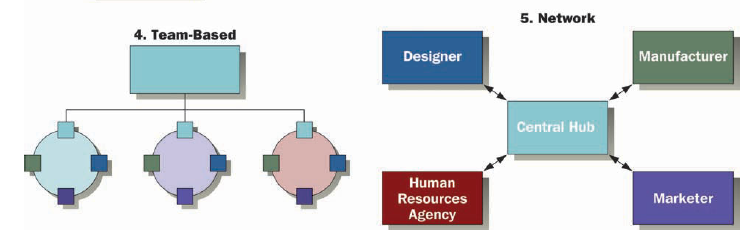

Another fundamental characteristic of organization structure is departmentalization, which is the basis for grouping positions into departments and departments into the total organization. Managers make choices about how to use the chain of command to group people together to perform their work. Five approaches to structural design reflect different uses of the chain of command in departmentalization, as illustrated in Exhibit 7.3. The functional, divisional, and matrix are traditional approaches that rely on the chain of command to define departmental groupings and reporting relationships along the hierarchy. Two innovative approaches are the use of teams and virtual networks, which have emerged to meet changing organizational needs in a turbulent global environment.

The basic difference among structures illustrated in Exhibit 7.3 is the way in which employees are departmentalized and to whom they report.21 Each structural approach is described in detail in the following sections.

1. VERTICAL FUNCTIONAL APPROACH

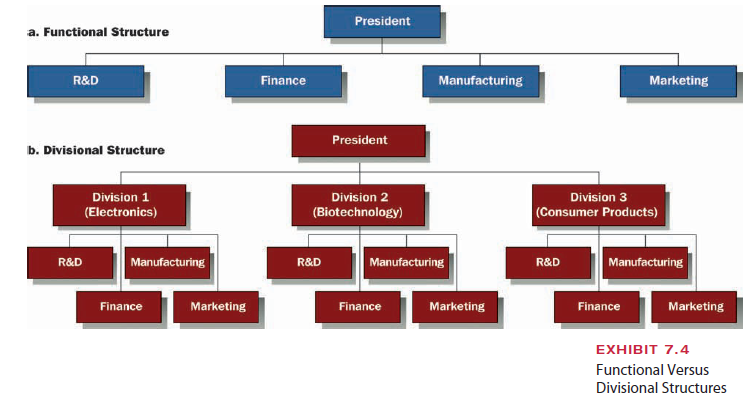

What It Is. Functional structure is the grouping of positions into departments based on similar skills, expertise, work activities, and resource use. A functional structure can be thought of as departmentalization by organizational resources because each type of functional activity—accounting, human resources, engineering, manufacturing—repre- sents specific resources for performing the organization’s task. People, facilities, and other resources representing a common function are grouped into a single department. One ex- ample is Blue Bell Creameries, which relies on in-depth expertise in its various functional departments to produce high-quality ice creams for a limited regional market. The quality control department, for example, tests all incoming ingredients and ensures that only the best go into Blue Bell’s ice cream. Quality inspectors also test outgoing products, and be- cause of their years of experience, can detect the slightest deviation from expected quality. Blue Bell also has functional departments such as sales, production, maintenance, distribu- tion, research and development, and finance.22

How It Works. Refer to Exhibit 7.1 (see page 249) for an example of a functional structure. The major departments under the president are groupings of similar expertise and resources, such as accounting, human resources, production, and marketing. Each of the functional departments is concerned with the organization as a whole. The marketing department is responsible for all sales and marketing, for example, and the accounting de- partment handles financial issues for the entire company.

The functional structure is a strong vertical design. Information flows up and down the vertical hierarchy, and the chain of command converges at the top of the organization. In a functional structure, people within a department communicate primarily with others in the same department to coordinate work and accomplish tasks or implement decisions that are passed down the hierarchy. Managers and employees are compatible because of similar training and expertise. Typically, rules and procedures govern the duties and responsibili- ties of each employee, and employees at lower hierarchical levels accept the right of those higher in the hierarchy to make decisions and issue orders.

2. DIVISIONAL APPROACH

What It Is. In contrast to the functional approach, in which people are grouped by common skills and resources, the divisional structure occurs when departments are grouped together based on organizational outputs. The divisional structure is sometimes called a product structure, program structure, or self-contained unit structure. Each of these terms means essentially the same thing: Diverse departments are brought together to pro- duce a single organizational output, whether it be a product, a program, or a service to a single customer.

Most large corporations have separate divisions that perform different tasks, use differ- ent technologies, or serve different customers. When a huge organization produces prod- ucts for different markets, the divisional structure works because each division is an auton- omous business. Microsoft has reorganized into three business divisions: Platform Products & Services (which includes Windows and MSN); Business (including Office and Business Solutions products); and Entertainment & Devices (Xbox games, Windows mobile, and Microsoft TV). Each unit is headed by a president who is accountable for the performance of the division, and each contains the functions of a standalone company, doing its own product development, sales, marketing, and finance. Facing new competitive threats from Google and makers of the free Linux operating system, top executives initiated the restruc- turing to help Microsoft be more flexible and nimble in developing and delivering new products. The structure groups together products and services that depend on similar tech- nologies, and at the same time, it enables more rapid decision making and less red tape at the giant corporation.23

How It Works. Functional and divisional structures are illustrated in Exhibit 7.4. In the divisional structure, divisions are created as self-contained units with separate func- tional departments for each division. For example, in Exhibit 7.4, each functional depart- ment resource needed to produce the product is assigned to each division. Whereas in a functional structure, all engineers are grouped together and work on all products, in a divisional structure, separate engineering departments are created within each division. Each department is smaller and focuses on a single product line or customer segment. Departments are duplicated across product lines.

The primary difference between divisional and functional structures is that the chain of command from each function converges lower in the hierarchy. In a divisional structure, dif- ferences of opinion among research and development, marketing, manufacturing, and finance would be resolved at the divisional level rather than by the president. Thus, the divisional structure encourages decentralization. Decision making is pushed down at least one level in the hierarchy, freeing the president and other top managers for strategic planning.

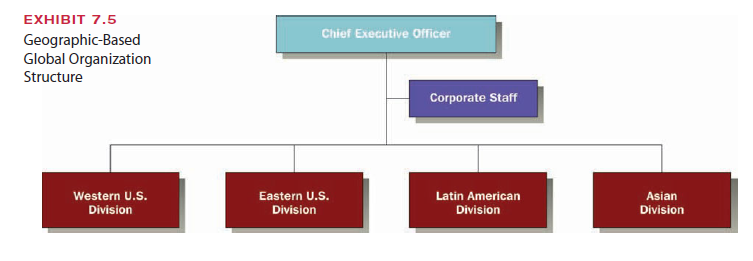

3. GEOGRAPHIC– OR CUSTOMER-BASED DIVISIONS

An alternative for assigning divisional responsibility is to group company activities by geo- graphic region or customer group. For example, the Internal Revenue Service shifted to a structure focused on four distinct taxpayer (customer) groups: individuals, small businesses, corporations, and nonprofit or government agencies.24 A global geographic structure is il- lustrated in Exhibit 7.5. In this structure, all functions in a specific country or region report to the same division manager. The structure focuses company activities on local market conditions. Competitive advantage may come from the production or sale of a product or service adapted to a given country or region. Colgate-Palmolive Company is organized into regional divisions in North America, Europe, Latin America, the Far East, and the South Pacific.25 The structure works for Colgate because personal care products often need to be tailored to cultural values and local customs.

Large nonprofit organizations such as the United Way, National Council of YMCAs, Habitat for Humanity International, and the Girl Scouts of the USA also frequently use a type of geographical structure, with a central headquarters and semiautonomous local units. The national organization provides brand recognition, coordinates fund-raising services, and handles some shared administrative functions, while day-to-day control and decision making are decentralized to local or regional units.26

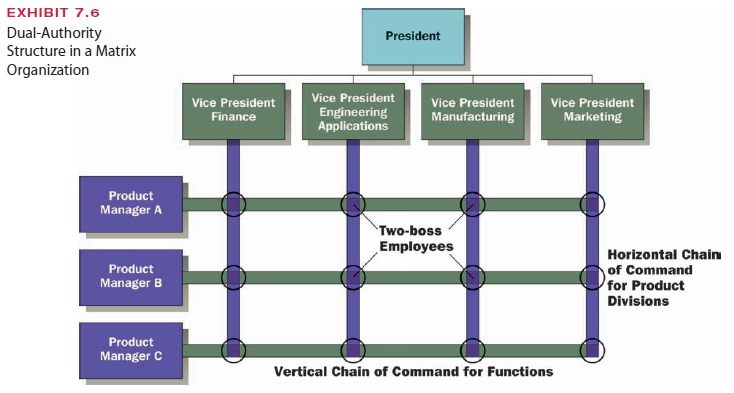

4. MATRIX APPROACH

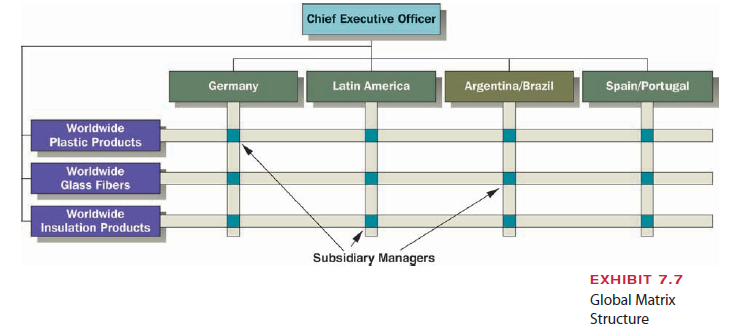

What It Is. The matrix approach combines aspects of both functional and divisional structures simultaneously in the same part of the organization. The matrix structure evolved as a way to improve horizontal coordination and information sharing.27 One unique feature of the matrix is that it has dual lines of authority. In Exhibit 7.6, the functional hierarchy of authority runs vertically, and the divisional hierarchy of authority runs horizontally. The vertical structure provides traditional control within functional departments, and the horizontal structure provides coordination across departments. The matrix structure therefore supports a formal chain of command for both functional (vertical) and divisional (horizontal) relationships. As a result of this dual structure, some employees actually report to two supervisors simultaneously.

How It Works. The dual lines of authority make the matrix unique. To see how the matrix works, consider the global matrix structure illustrated in Exhibit 7.7. The two lines of authority are geographic and product. The geographic boss in Germany coordinates all sub- sidiaries in Germany, and the plastics products boss coordinates the manufacturing and sale of plastics products around the world. Managers of local subsidiary companies in Germany would report to two superiors, both the country boss and the product boss. The dual authority struc- ture violates the unity-of-command concept described earlier in this chapter but is necessary to give equal emphasis to both functional and divisional lines of authority. Dual lines of au- thority can be confusing, but after managers learn to use this structure, the matrix provides ex- cellent coordination simultaneously for each geographic region and each product line.

The success of the matrix structure depends on the abilities of people in key matrix roles. Two-boss employees, those who report to two supervisors simultaneously, must resolve conflicting demands from the matrix bosses. They must confront senior managers and reach joint decisions. They need excellent human relations skills with which to confront managers and resolve conflicts. The matrix boss is the product or functional boss, who is responsible for one side of the matrix. The top leader is responsible for the entire matrix. The top leader oversees both the product and functional chains of command. His or her responsibility is to maintain a power balance between the two sides of the matrix. If dis- putes arise between them, the problem will be kicked upstairs to the top leader.28

5. TEAM APPROACH

What It Is. Probably the most widespread trend in departmentalization in recent years has been the implementation of team concepts. The vertical chain of command is a power- ful means of control, but passing all decisions up the hierarchy takes too long and keeps responsibility at the top. The team approach gives managers a way to delegate authority, push responsibility to lower levels, and be more flexible and responsive in the competitive global environment.

How It Works. One approach to using teams in organizations is through cross- functional teams, which consist of employees from various functional departments who are responsible to meet as a team and resolve mutual problems. Team members typically still report to their functional departments, but they also report to the team, one member of whom may be the leader. Cross-functional teams are used to provide needed horizontal coordination to complement an existing divisional or functional structure. A frequent use of cross-functional teams is for change projects, such as a new product or service innovation.

A cross-functional team of mechanics, flight attendants, reservations agents, ramp work-ers, luggage attendants, and aircraft cleaners, for example, collaborated to plan and design a new low-fare airline for US Airways.29

The second approach is to use permanent teams, groups of employees who are brought together in a way similar to a formal department. Each team brings together em- ployees from all functional areas focused on a specific task or project, such as parts supply and logistics for an automobile plant. Emphasis is on horizontal communication and infor- mation sharing because representatives from all functions are coordinating their work and skills to complete a specific organizational task. Authority is pushed down to lower levels, and front-line employees are often given the freedom to make decisions and take action on their own. Team members may share or rotate team leadership. With a team-based structure, the entire organization is made up of horizontal teams that coordinate their work and work directly with customers to accomplish the organization’s goals. Imagination Ltd., Britain’s largest design firm, is based entirely on teamwork. Imagination puts to- gether a diverse team at the beginning of each new project it undertakes, whether it be cre- ating the lighting for Disney cruise ships or redesigning the packaging for Ericsson’s cell phone products. The team then works closely with the client throughout the project.30

Imagination Ltd. has managed to make every project a smooth, seamless experience by building a culture that supports teamwork.

6. THE VIRTUAL NETWORK APPROACH

What It Is. The most recent approach to departmentalization extends the idea of hori- zontal coordination and collaboration beyond the boundaries of the organization. In a vari- ety of industries, vertically integrated, hierarchical organizations are giving way to loosely interconnected groups of companies with permeable boundaries.31 Outsourcing, which means farming out certain activities, such as manufacturing or credit processing, has become a sig- nificant trend. In addition, partnerships, alliances, and other complex collaborative forms are now a leading approach to accomplishing strategic goals. In the music industry, firms such as Vivendi Universal and Sony have formed networks of alliances with Internet service providers, digital retailers, software firms, and other companies to bring music to customers in new ways.32 Some organizations take this networking approach to the extreme to create an innovative structure. The virtual network structure means that the firm subcontracts most of its major functions to separate companies and coordinates their activities from a small headquarters organization.33 Indian telecom company Bharti Tele-Ventures Ltd., for example, outsources everything except marketing and customer management.34

How It Works. The organization may be viewed as a central hub surrounded by a network of outside specialists, as illustrated in Exhibit 7.8. Rather than being housed under one roof, services such as accounting, design, manufacturing, and distribution are out- sourced to separate organizations that are connected electronically to the central office.35

Networked computer systems, collaborative software, and the Internet enable organiza- tions to exchange data and information so rapidly and smoothly that a loosely connected network of suppliers, manufacturers, assemblers, and distributors can look and act like one seamless company.

The idea behind networks is that a company can concentrate on what it does best and contract out other activities to companies with distinctive competence in those specific areas, which enables a company to do more with less.36 The Birmingham, England-based company, Strida, provides an example of the virtual network approach.

With a network structure such as that used at Strida, it is difficult to answer the ques- tion, “Where is the organization?” in traditional terms. The different organizational parts may be spread all over the world. They are drawn together contractually and coordinated electronically, creating a new form of organization. Much like building blocks, parts of the network can be added or taken away to meet changing needs.37

A similar approach to networking is called the modular approach, in which a manu-facturing company uses outside suppliers to provide entire chunks of a product, which are then assembled into a final product by a handful of workers. The Canadian firm Bombar- dier’s new Continental business jet is made up of about a dozen huge modular components from all over the world: the engines from the United States; the nose and cockpit from Canada; the mid-fuselage from Northern Ireland; the tail from Taiwan; the wings from Japan; and so forth.39 Automobile plants, including General Motors, Ford, Volkswagen, and DaimlerChrysler, are leaders in using the modular approach. The modular approach hands off responsibility for engineering and production of entire sections of an automobile, such as the chassis or interior, to outside suppliers. Suppliers design a module, making some of the parts themselves and subcontracting others. These modules are delivered right to the assembly line, where a handful of employees bolt them together into a finished vehicle.40

7. ADVANTAGES AND DISADVANTAGES OF EACH STRUCTURE

Each of these approaches to departmentalization—functional, divisional, matrix, team, and virtual network—has strengths and weaknesses. The major advantages and disadvan- tages of each are listed in Exhibit 7.9.

Functional Approach. Grouping employees by common task permits economies of scale and efficient resource use. For example, at American Airlines, all IT people work in the same, large department. They have the expertise and skills to handle almost any IT problem for the organization. Large, functionally based departments enhance the develop- ment of in-depth skills because people work on a variety of related problems and are associ- ated with other experts within their own department. Because the chain of command con- verges at the top, the functional structure also provides a way to centralize decision making and provide unified direction from top managers. The primary disadvantages reflect barri- ers that exist across departments Because people are separated into distinct departments, communication and coordination across functions are often poor, causing a slow response to environmental changes. Innovation and change require involvement of several depart- ments. Another problem is that decisions involving more than one department may pile up at the top of the organization and be delayed.

Divisional Approach. By dividing employees and resources along divisional lines, the organization will be flexible and responsive to change because each unit is small and tuned in to its environment. By having employees working on a single product line, the concern for customers’ needs is high. Coordination across functional departments is better because employees are grouped together in a single location and committed to one product line. Great coordination exists within divisions; however, coordination across divisions is often poor. Problems occurred at Hewlett-Packard, for example, when autonomous divisions went in opposite directions. The software produced in one division did not fit the hardware produced in another. Thus, the divisional structure was realigned to establish adequate coordination across divisions. Another major disadvantage is the duplication of resources and the high cost of running separate divisions. Instead of a single research department in which all research people use a single facility, each division may have its own research facility. The organization loses efficiency and economies of scale. In addition, the small size of departments within each division may result in a lack of technical specialization, expertise, and training.

Matrix Approach. The matrix structure is controversial because of the dual chain of command. However, the matrix can be highly effective in a complex, rapidly changing environment in which the organization needs to be flexible and adaptable.41 The conflict and frequent meetings generated by the matrix allow new issues to be raised and resolved. The matrix structure makes efficient use of human resources because specialists can be transferred from one division to another. The major problem is the confusion and frustra- tion caused by the dual chain of command. Matrix bosses and two-boss employees have difficulty with the dual reporting relationships. The matrix structure also can generate high conflict because it pits divisional against functional goals in a domestic structure, or prod- uct line versus country goals in a global structure. Rivalry between the two sides of the ma- trix can be exceedingly difficult for two-boss employees to manage. This problem leads to the third disadvantage: time lost to meetings and discussions devoted to resolving this con- flict. Often the matrix structure leads to more discussion than action because different goals and points of view are being addressed. Managers may spend a great deal of time co-ordinating meetings and assignments, which takes time away from core work activities.42

Team Approach. The team concept breaks down barriers across departments and improves cooperation. Team members know one another’s problems and compromise rather than blindly pursue their own goals. The team concept also enables the organization to more quickly adapt to customer requests and environmental changes and speeds decision making because decisions need not go to the top of the hierarchy for approval. Another big advantage is the morale boost. Employees are enthusiastic about their involvement in big- ger projects rather than narrow departmental tasks. At video games company Ubisoft, for example, each studio is set up so that teams of employees and managers work collabora- tively to develop new games. Employees don’t make a lot of money, but they’re motivated by the freedom they have to propose new ideas and put them into action.43

However, the team approach has disadvantages as well. Employees may be enthusiastic about team participation, but they may also experience conflicts and dual loyalties. A cross- functional team may make different demands on members than do their department man- agers, and members who participate in more than one team must resolve these conflicts. A large amount of time is devoted to meetings, thus increasing coordination time. Unless the organization truly needs teams to coordinate complex projects and adapt to the environ- ment, it will lose production efficiency with them. Finally, the team approach may cause too much decentralization. Senior department managers who traditionally made decisions might feel left out when a team moves ahead on its own. Team members often do not see the big picture of the corporation and may make decisions that are good for their group but bad for the organization as a whole.

Virtual Network Approach. The biggest advantages to a virtual network ap- proach are flexibility and competitiveness on a global scale. The extreme flexibility of a network approach is illustrated by today’s “war on terrorism.” Most experts agree that the primary reason the insurgency is so difficult to fight is that it is a far-flung collection of groups that share a specific mission but are free to act on their own. “Attack any single part of it, and the rest carries on largely untouched,” wrote one journalist after talking with U.S. and Iraqi officials. “It cannot be decapitated because the insurgency, for the most part, has no head.”44 One response is for the United States and its allies to organize into networks to quickly change course, put new people in place as needed, and respond to situations and challenges as they emerge.45

Today’s business organizations can also benefit from a flexible network approach that lets them shift resources and respond quickly. A network organization can draw on re- sources and expertise worldwide to achieve the best quality and price and can sell its prod- ucts and services worldwide. Flexibility comes from the ability to hire whatever services are needed and to change a few months later without constraints from owning plant, equip- ment, and facilities. The organization can continually redefine itself to fit new product and market opportunities. This structure is perhaps the leanest of all organization forms be- cause little supervision is required. Large teams of staff specialists and administrators are not needed. A network organization may have only 2 or 3 levels of hierarchy, compared with 10 or more in traditional organizations.46

One of the major disadvantages is lack of hands-on control. Managers do not have all operations under one roof and must rely on contracts, coordination, negotiation, and elec- tronic linkages to hold things together. Each partner in the network necessarily acts in its own self-interest. The weak and ambiguous boundaries create higher uncertainty and greater demands on managers for defining shared goals, coordinating activities, managing relationships, and keeping people focused and motivated.47 Finally, in this type of organi- zation, employee loyalty can weaken. Employees might feel they can be replaced by contract services. A cohesive corporate culture is less likely to develop, and turnover tends to be higher because emotional commitment between organization and employee is weak.

Source: Daft Richard L., Marcic Dorothy (2009), Understanding Management, South-Western College Pub; 8th edition.

Hello! I could have sworn I’ve been to this blog before but after browsing through some of the post I realized it’s new to me. Anyways, I’m definitely happy I found it and I’ll be book-marking and checking back frequently!