Rubin reconstructs the reason for what Kohler called the stimulus error as the inconsistent use of descriptions in which terms denoting geometric and perceptual properties occur without specification of their intended interpretation. The use of the same terms to denote everyday material objects, visual objects and figures of elementary geometry, as well as the idealization of material objects like points and lines, is the source of many epistemological mistakes. In fact, Rubin claims that there is no contradiction between the objects of the visual world and the properties of geometrical figures unless one is biased to believe that the latter should account for the former because of this equivocal linguistic use (1950: 380). For example, the “Muller-Lyer/Brentano” figure shows that the contradiction between what is seen and what is known on the grounds of metrical measures arises only when a comparison of the two lines is made by indirect means (1950: 365). If one adheres strictly to what naive perceivers see, there is nothing odd in the lines; hence, there is no contradiction between perception and geometry. Indeed, the finding that the angular sectors influence the visual length contrasts only with the belief that what is seen must represent the physical magnitudes at least for objects at short distances. However, this belief derives from the assumption that the perception of quantitative properties depends solely upon the physical properties of objects that are considered the only “real” ones. Instead, the perception of lengths, angles and distances has to be distinguished from knowledge of the geometrical properties as much as the perception of colors does from the knowledge of electromagnetic waves. In a manner similar to Brentano’s arguments on non-perceptual belief, which is necessarily associated with appearances, and on the need to distinguish between causal and descriptive explanations of perception, Rubin argues that the contradiction arises when, instead of perceiving the length of the two lines, one makes a comparative judgement on it by assuming that perceived length must represent the metric property obtained through measurement instruments. On the contrary, the Muller-Lyer figure is a “device” to detect the cases when the linguistic denotation biases the same treatment for the phenomenal and geometric properties, thus leading to the assumption that the study of the spatial properties of visual figures derives from the axioms of abstract geometry (1950: 373-377).

Rubin puts forth the case of a straight line whose middle point is marked. If one angular sector of the Muller-Lyer device is joined to the middle point, this point no longer appears to divide the line into two parts that appear equal. This point is seen to be the same as before, when it did visually divide the line into two equal halves, and it is known to be by definition something that lies at the middle of the line; however, this is not visually the case. To satisfy visually the geometrical definition, the point should be laterally displaced. In order to emphasize the meaning of such observations, Rubin presents three lines simultaneously to subjects. The first is a straight line with a marked middle point. The second is the same line with an angular sector joined to the middle point. The third is the same straight line with the angular sector, whose marked middle point is displaced laterally on the right or the left according to the acute or obtuse angle of the joined sector. Rubin reports that subjects agree in seeing the straight line with the angular sector and the displaced middle point as “the same” as the first line. He then claims that for this to make sense, one should conclude that this third line appears as the equivalent inside the Muller-Lyer device of the first line, which is divided into two metrically and visually equal segments.

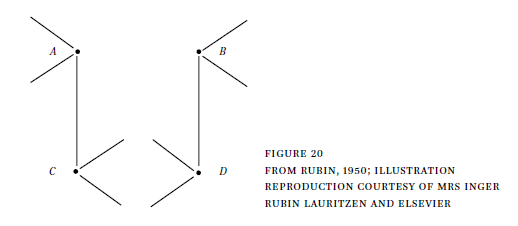

This is a case in which the visual and geometrical objects are made to converge in direct experience. However, Rubin contends that in general the perception of sameness or identity is always a matter that needs an explanation independent of geometry. He claims that the contradiction also is not real when it concerns a visual object itself, not only when the visual experience is compared to measurement results. Consider the figure:

Here the seeming contradiction with geometry stems from the very construction of the figure. AB is seen to be longer than and parallel to CD. If this appearance is translated into the geometrical inequalities (AB > CD) A (AB * CD), it should imply that AC and BD converge to a point below CD, but AC and BD appear to be parallel to each other. Moreover, AC and BD are seen as parallel to each other and perpendicular to both AB and CD. This geometrically implies that AB and CD are equal, while they appear unequal. This proves that the contradiction does not stem from the perception as such. It arises because the appearances are judged according to geometric relations that are applied to them, because words such as “parallel” and “perpendicular” denote phenomenal and geometric entities. In spite of the linguistic denotation, the relations among the phenomenal figures may differ from those that hold among geometrical figures. When this difference is conspicuous, it is more appropriate to talk of paradox rather than illusion. In fact, even the paradox arises because certain relations and changes may affect only local spatial properties rather than the whole perceptual figure, unlike what is the case in geometry.

Rubin emphasizes that analytical or abstract geometry is axiomatic, so that its propositions are only valid for arbitrary objects provided they satisfy the relations deduced from the axioms. Yet the idealized objects of elementary geometry are considered the entities to which the material things of everyday life approximate, given their denotation by means of the same words. If perception is accounted as the representation of material things, then the geometrical properties cannot but be the real determinants of perception. If this assumption becomes the tenet of a theory, the theory cannot recognize that the rules of perception are self-consistent and that the seeming contradiction between the mere perceptual and the real geometric properties derives from the erroneous application of two kinds of description to the perceptual figures.

Source: Calì Carmelo (2017), Phenomenology of Perception: Theories and Experimental Evidence, Brill.

23 Oct 2019

10 Aug 2021

11 Aug 2021

11 Aug 2021

11 Aug 2021

10 Aug 2021