1. Feasibility analysis

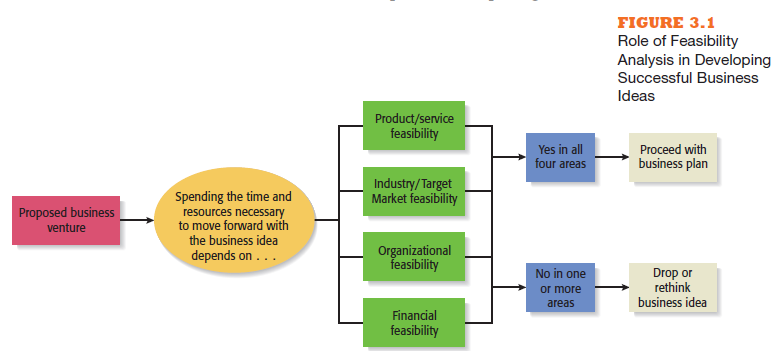

Feasibility analysis is the process of determining if a business idea is viable (see Figure 3.1). If a business idea falls short on one or more of the four compo- nents of feasibility analysis, it should be dropped or rethought, as shown in the figure. Many entrepreneurs make the mistake of identifying a business idea and then jumping directly to developing a business model (see Chapter 4) to describe and gain support for the idea. This sequence often omits or provides little time for the important step of testing the feasibility of a business idea.

A mental transition must be made when completing a feasibility analysis from thinking of a business idea as just an idea to thinking of it as a business. A feasibility analysis is an assessment of a potential business rather than strictly a product or service idea. The sequential nature of the steps shown in Figure 3.1 cleanly separates the investigative portion of thinking through the merits of a business idea from the planning and selling portion of the process. Feasibility analysis is investigative in nature and is designed to critique the merits of a proposed business. A business plan (see Chapter 6) is more focused on planning and selling. The reason it’s important to complete the entire pro- cess, according to John W. Mullins, the author of the highly regarded book The New Business Road Test, is to avoid falling into the “everything about my op- portunity is wonderful” mode. In Mullins’s view, failure to properly investigate the merits of a business idea before developing a business model and a busi- ness plan is written runs the risk of blinding an entrepreneur to inherent risks associated with the potential business and results in too positive of a plan.1

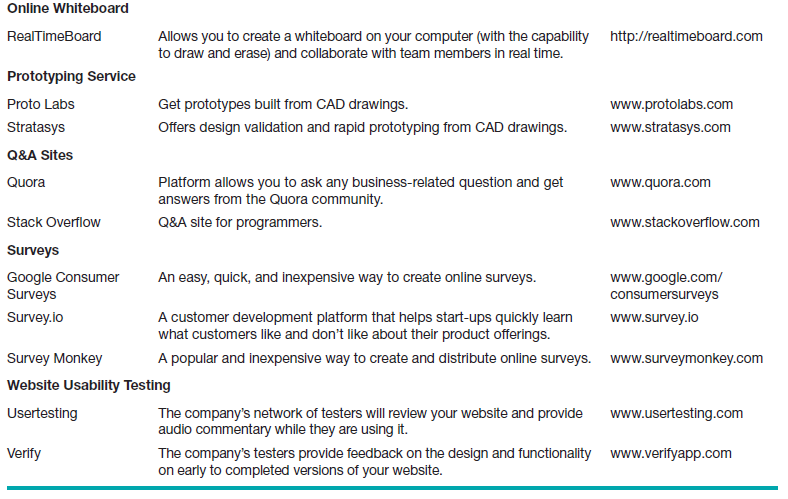

This chapter provides a methodology for conducting a feasibility analysis by describing its four key areas: product/service feasibility, industry/target market feasibility, organizational feasibility, and financial feasibility. We intro- duce supplemental material in two appendixes to the chapter. Appendix 3.1 contains a tool called First Screen, which is a template for completing a feasi- bility analysis. Appendix 3.2 contains an Internet Resource Table that provides information on Internet resources that are helpful in completing First Screen.

An outline for the approach to feasibility analysis we describe in this chapter is provided in Table 3.1. Completing a feasibility analysis requires both primary and secondary research. Primary research is research that is collected by the person or persons completing the analysis. It normally includes talking to pro- spective customers, getting feedback from industry experts, conducting focus groups, and administering surveys. Secondary research probes data that is already collected. The data generally includes industry studies, Census Bureau data, analyst forecasts, and other pertinent information gleaned through li- brary and Internet research. The Internet Resource Table in Appendix 3.2 is useful for conducting secondary research.

It should be emphasized that while a feasibility analysis tests the merits of a specific idea, it allows ample opportunity for the idea to be revised, altered, and changed as a result of the feedback that is obtained and the analysis that is conducted. The key objective behind feasibility analysis is to put an idea to the test—by eliciting feedback from potential customers, talking to indus- try experts, studying industry trends, thinking through the financials, and scrutinizing it in other ways. These types of activities not only help determine whether an idea is feasible but also help shape and mold the idea.

Now let’s turn our attention to the four areas of feasibility analysis. The first area we’ll discuss is product/service feasibility.

2. Product/ser vice Feasibility analysis

Product/service feasibility analysis is an assessment of the overall appeal of the product or service being proposed. Although there are many important things to consider when launching a new venture, nothing else matters if the product or service itself doesn’t sell. There are two components to product/service feasibility analysis: product/service desirability and product/service demand.

2.1. Product/Service desirability

The first component of product/service feasibility is to affirm that the pro- posed product or service is desirable and serves a need in the marketplace.

You should ask yourself, and others, the following questions to determine the basic appeal of the product or service:

■ Does it make sense? Is it reasonable? Is it something real customers will buy?

■ Does it take advantage of an environmental trend, solve a problem, or fill a gap in the marketplace?

■ Is this a good time to introduce the product or service to the market?

■ Are there any fatal flaws in the product or service’s basic design or concept?

The proper mind-set at the feasibility analysis stage is to get a general sense of the answers to these and similar questions, rather than to try to reach final conclusions. The best way to achieve this is to “get out of the building” and talk to potential customers. This sentiment is the primary mantra of the lean startup movement, referred to in more detail in Chapter 6. A tool that is particularly useful in soliciting feedback and advice from prospective custom- ers is to administer a concept test.

Concept Test A concept test involves showing a preliminary description of a product or service idea, called a concept statement, to industry experts and prospective customers to solicit their feedback. It is a one-page document that normally includes the following:

■ A description of the product or service. This section details the features of the product or service; many include a sketch of it as well.

■ The intended target market. This section lists the consumers or busi- nesses who are expected to buy the product or service.

■ The benefits of the product or service. This section describes the benefits of the product or service and includes an account of how the product or service adds value and/or solves a problem.

■ A description of how the product or service will be positioned relative to competitors. A company’s position describes how its product or service is situated relative to its rivals.

■ A brief description of the company’s management team.

After the concept statement is developed, it should be shown to at least 20 people who are familiar with the industry that the firm plans to enter and who can provide informed feedback. The temptation to show it to family members and friends should be avoided because these people are predisposed to give positive feedback. Instead, it should be distributed to people who will provide candid and informed feedback and advice.

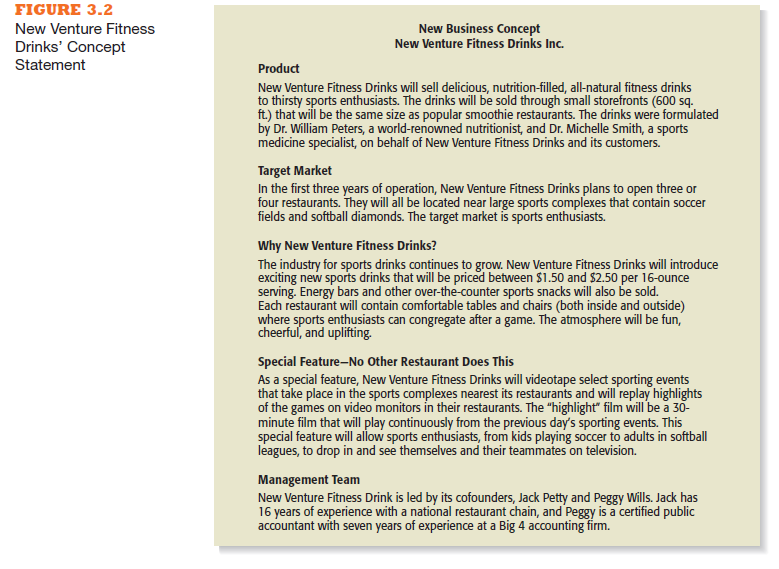

The concept statement for a fictitious company named New Venture Fitness Drinks is provided in Figure 3.2. New Venture Fitness Drinks sells a line of nutritious fitness drinks and targets sports enthusiasts. Its strategy is to place small restaurants, similar to smoothie restaurants, near large sports complexes. It is important to keep a concept statement relatively short (no more than one page) to increase the likelihood that it will be read. The concept statement is followed by a short buying intentions survey. The information gleaned from the survey should be tabulated and carefully read. If time permits, the statement can be used in an iterative manner to strengthen the product or service idea. For example, you might show the statement to a group of prospective customers, receive their feedback, tweak the idea, show it to a second group of customers, tweak the idea some more, and so on.

The problem with not talking to potential customers prior to starting a business is that it’s hard to know if a product is sufficiently desirable based simply on gut instinct or secondary research. A common reason new busi- nesses fail is that there isn’t a large enough market for the venture’s product. This scenario played out for Matt Cooper, who was a partner in a business called Soggy Bottom Canoe and Kayak Rental. It was his first start-up and turned out to be, as Cooper put it, an “unmitigated disaster.” Cooper and his partner owned 10 acres near a national forest in Mississippi, where they de- cided to launch a canoe rental business. They invested heavily in finishing out the facilities on the property and bought 32 canoes, 16 kayaks, 4 trailers, and 2 vans. They opened on a July 4th weekend and everything was immaculate. The following is what happened, in Cooper’s words:

“In our quest to have the best facilities and equipment, we neglected to speak to a single prospective customer. No Boy Scout troops, no church youth groups, no fraternities from Southern Mississippi University. As a result, I can count on only one hand the number of times, in the seven years that we owned the business, that we reached even half of our booking capacity.2

Cooper goes on to admit that he’s learned his lesson. Reflecting on his Soggy Bottom Canoe and Kayak Rental experience he said:

“Today, I still fight against the urge to make big investments before we’ve “beta tested.” Every time that urge pops up, I picture gleaming new canoes hitched up to sad empty passenger vans.”3

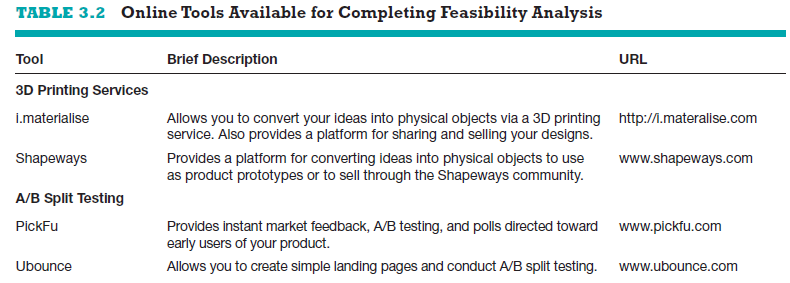

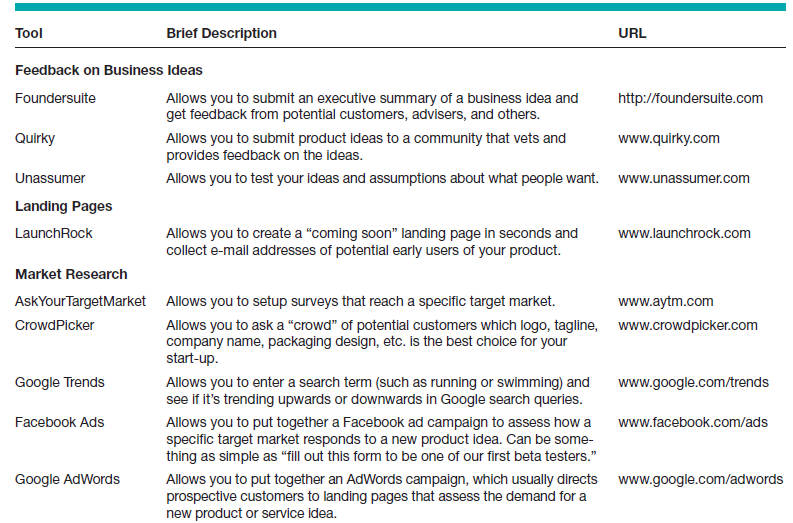

Rather than developing a formal concept statement, some entrepreneurs conduct their initial product/service feasibility analysis by simply talking through their ideas with prospective customers or conducting focus groups to solicit feedback. The ideal combination is to do both—distribute a concept statement to 20 or more people who can provide informed feedback and engage in verbal give-and-take with as many industry experts and prospective custom- ers as possible. There are also a growing number of online tools that help entre- preneurs quickly and inexpensively make contact with prospective customers and complete other steps in the feasibility analysis process. These tools range from services like Quirky, which provides direct feedback on product ideas, to 3D printing services like Shapeways, which converts CAD drawings of product ideas into physical prototypes that you can show to potential customers. We provide a sample of the online tools that are available in Table 3.2.

2.2. Product/Service demand

The second component of product/service feasibility analysis is to determine if there is demand for the product or service. Three commonly utilized methods for doing this include (1) talking face-to-face with potential customers, (2) utiliz- ing online tools, such as Google Adwords and landing pages, to assess demand, and (3) library, Internet, and gumshoe research.

Talking Face-to-Face with Potential Customers The only way to know if your product or service is what people want is by talking to them. Curiously, this often doesn’t happen. One study of 120 business founders revealed that more than half fully developed their products without getting feedback from potential buyers.4 In hindsight, most viewed it as a mistake. The authors of the study quoted one of the participants as saying “You’ll learn more from talking to five customers than you will from hours of market research (at a computer).” The idea is to gauge customer reaction to the general concept of what you want to sell. Entrepreneurs are often surprised to find out that a product idea that they think solves a compelling problem gets a lukewarm reception when they talk to actual customers.

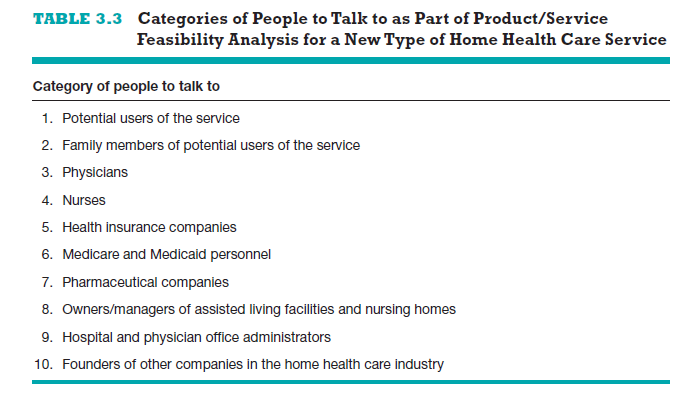

In some instances, you have to pause and think carefully about who the potential customer is. For example, in health care the “customer” is typically not the patient who will use the drugs or benefit from a medical procedure. Instead the actual customer, or the entity that will be paying the bill, is often an insurance company, hospital, or Medicare or Medicaid. You should also talk to as many of the relevant players in an industry as possible. Sometimes this involves a complex list of people, but it is necessary to fully vet the initial feasibility of an idea. For example, say you were thinking about launching an innovative new type of home health care service. The service would allow elderly people to stay in their homes longer before going into assisted living or a nurs- ing home, and it would help people remember to take their medicine on time and provide other health care monitoring services. Table 3.3 contains a list of the categories of people that you might want to talk to as part of your product/ service feasibility analysis. While the list is long, imagine the rich insight that you could get on your business idea from people in these categories.

One approach to finding qualified people to talk to about a product or ser- vice idea or to react to a concept statement is to contact trade associations and/or attend industry trade shows. If your product idea is in the digital me- dia space, for example, you may be able to call the Digital Media Association (which is a national trade association devoted primarily to the online audio and video industries) and get a list of members who live in your area. Attending trade shows in the industry you’re interested in will place you in direct contact with numerous people who might be of assistance. A website that provides a directory of trade associations is included in the Internet Resource Table in Appendix 3.2. Online surveys are also useful to reach a large number of people quickly. Services such as SurveyMonkey and AYTM are making it increasingly easy to survey specific target markets and receive detailed analytics for a very affordable price.

Utilizing Online Tools, Such as google adWords and landing Pages, to assess Demand Another common approach to assessing product de- mand is to use online tools, such as Google AdWords and landing pages. The way this works is as follows. Suppose you’ve developed a new type of sunglasses for snowboarders and want to assess likely demand. One way of doing this is to buy keywords on the Google search page like “snowboarding” and “sunglasses.” You can purchase the keywords through Google’s AdWords program. Once you buy the keywords, when someone searches for the term “snowboarding” or “sunglasses” a link to an ad you’ve prepared will show up either at the top or to the right of the organic search results. The text below the link will say something such as “Innovative new sunglasses for snowboarders.” If someone clicks on the link, they’ll be taken to what online marketers call a landing page. A landing page is a single Web page that typically provides direct sales copy, like “click here to buy a Hawaiian vacation.” Your landing page, which can be inexpen- sively produced through a company like LaunchRock (see Table 3.2), will show an artist’s depiction of your innovative new sunglasses, provide a brief explana- tion, and will then say something like “Coming Soon—Please Enter Your E-mail Address for Updates.” How often your ad appears will depend on what you purchase through Google’s automated AdWord’s keyword auction. Google will provide you analytics regarding how many people click on the ad and how many follow through and provide their e-mail address. You can also capture the e-mail addresses that are provided.

The beauty of using Google AdWords is that the people who click on the ad were either searching for the term “snowboarding” or “sunglasses” or they wouldn’t have seen the ad. So you’re eliciting responses from a self-selected group of potential buyers. The overarching purpose is to get a sense of inter- est in your product. If, over a three-day period, 10,000 people click on the ad and 4,000 provide their e-mail address to you, that might signal a fairly strong interest in the product. On the other hand, if only 500 people click on the ad and 50 give you their e-mail address, that’s a much less affirming response. It’s strictly a judgment call regarding how many clicks represent an encourag- ing response to your product idea. Normally, utilizing an AdWords and landing page campaign wouldn’t be the only thing you’d do to assess demand. You’d still want to talk to prospective customers face-to-face, as discussed earlier. Running an AdWords and landing page campaign is, however, a practical and often surprisingly affordable way to get another data point in regard to assess- ing demand for a new product or service idea.

Library, internet, and gumshoe research The third way to assess demand for a product or service idea is by conducting library, Internet, and gumshoe research. While talking to prospective customers is critical, collect- ing secondary data on an industry is also helpful. For example, Spring Toys makes super-safe, environmentally friendly, educational toys for children.

Sounds like a good idea. But “sounds like a good idea,” as mentioned in previ- ous sections, isn’t enough. We need feedback from prospective customers and industry-related data to make sure. Industry-related data can help us answer the following types of questions: What’s the trajectory of the toy industry? What do industry experts say are the most important factors that parents con- sider when they buy their children toys? Is there an “educational toy” segment within the larger toy industry? If so, is this segment growing or shrinking? Is there a trade association for the makers of educational toys that already has statistics about the market demand for educational toys?

The overarching point is that for your particular product or service you need archival as well as primary forms of research to assess likely demand. Your university or college library is a good place to start, and the Internet is a marvelous resource. The Internet Resource Table in Appendix 3.2 provides spe- cific recommendations of online resources to utilize. For example, IBISWorld, which is available for free through most university libraries, provides current industry reports on hundreds of industries. Its report on the toy industry, which is frequently updated, is titled “Toy, Doll and Game Manufacturing in the US (NAICS 33993).” This report would be a good place to start in terms of understanding relevant industry trends. More general Internet research is also often helpful. Simply typing a query into the Google or Bing search bar such as “market demand for educational toys” will often produce helpful articles and industry reports.

Simple gumshoe research is also important for gaining a sense of the likely demand for a product or service idea. A gumshoe is a detective or an investiga- tor that scrounges around for information or clues wherever they can be found. Don’t be bashful. Ask people what they think about your product or service idea. If your idea is to sell educational toys, spend a week volunteering at a day care center and watch how children interact with toys. Take the owner of a toy store to lunch and discuss your ideas. Spend some time browsing through toy stores and observe the types of toys that get the most attention. If you actually launch a business, there is simply too much at stake to rely on gut instincts and cursory information to assure you that your product or service will sell. Collect as much information as you can within reasonable time constraints.

The importance of library, Internet, and gumshoe research doesn’t wane once a firm is launched. It’s important to continually assess the strength of product or service ideas and learn from users. A colorful example of the value of ongoing gumshoe research is provided in the “Savvy Entrepreneurial Firm” feature. In this feature, a successful company made a 180-degree turn regard- ing how to position a particular product simply by watching how customers interacted with the product in retail stores.

Source: Barringer Bruce R, Ireland R Duane (2015), Entrepreneurship: successfully launching new ventures, Pearson; 5th edition.

Hello.This post was extremely motivating, particularly since I was browsing for thoughts on this topic last Monday.