In this section we look at the social and cultural impacts of the Internet. These are important from an e-commerce perspective since they govern demand for Internet services and propensity to purchase online. For example, in Figures 1.10 and 1.14 respectively we saw how businesses and consumers have adopted different online services.

Further aspects of the social influence of the Internet are described in the references to the Information Society Initiative in this chapter and in the section on the online buying process (Chapter 9). Complete Activity 4.2 to start to review some of the social issues associated with the Internet.

1. Factors governing e-commerce service adoption

It is useful for e-business managers to understand the different factors that affect how many people actively use the Internet. If these are understood for customers in a target market, action can be taken to overcome some of these barriers. For example, marketing communications can be used to reduce fears about the value proposition, ease of use and security. Chaffey et al. (2009) suggest that the following factors are important in governing adoption of any e-commerce service:

- Cost of access. This is certainly a barrier for those who do not already own a home computer: a major expenditure for many households. The other main costs are the cost of using an ISP to connect to the Internet and the cost of using the media to connect (telephone or cable charges). Free access would certainly increase adoption and usage.

- Value proposition. Customers need to perceive a need to be online – what can the Internet offer that other media cannot? Examples of value propositions include access to more supplier information and possibly lower prices. In 2000, company advertisements started to refer to ‘Internet prices’.

- Ease of use. This includes the ease of first connecting to the Internet using the ISP and the ease of using the web once connected.

- Security While this is only, in reality, a problem for those who shop online, the perception generated by news stories may be that if you are connected to the Internet then your personal details and credit card details may not be secure. It will probably take many years for this fear to diminish as using the Internet slowly becomes established as a standard way of purchasing goods.

- Fear of the unknown. Many will simply have a general fear of the technology and the new media, which is not surprising since much of the news about the Internet non-adopters will have heard will concern pornography, fraud and privacy infringements.

An attempt has been made to quantify the magnitude of barriers to access in a UK government-sponsored survey (Booz Allen Hamilton, 2002) of different countries. Barriers for individuals noted by the survey included:

- No perceived benefit

- Lack of trust

- Security problems

- Lack of skills

- Cost.

The authors of the report note that:

significant (national) variation exists in what citizens perceive to be the most important barriers to further use, and in governments’ chosen role in tackling those barriers. Using the internet and ICTs in education seems to be a significant driver of citizens’ confidence in their own skills. Several governments, notably Italy and France, have attempted to tackle the skill issue later in life through a range of courses in computer skills.

As expected, there is a strong correlation between Internet use and PC penetration. Countries such as Sweden have encouraged home use most actively through government initiatives, in this case the ‘PC REFORM’ programme. This appears to exert more influence than reduction in lower costs of access, since in leading countries such as Sweden and Australia, cost is relatively high.

1.1. Understanding users’ access requirements

To fully understand online customer propensity to use online service we also need to consider the user’s access location, access device and ‘webographics’, which can help target certain types of customers and are an important constraint on site design. ‘Webographics’ is a term coined by Grossnickle and Raskin (2001). According to these authors webographics includes:

- Usage location (in most countries, many users access either from home or from work, with home being the more popular choice)

- Access device (browser and computer platform described in Chapter 3 including mobile devices)

- Connection speed – broadband versus dial-up connections

- ISP

- Experience level

- Usage type

- Usage level.

Competition in the marketplace amongst broadband providers has caused a great increase in the broadband Internet access options available for consumers and small businesses. But it should be borne in mind that these vary significantly by country as shown by Figure 4.2. They show the web services should be tested for lower-speed Internet access.

Variations in usage of mobile services are shown in Table 4.3. You can see that this type of data is vital for managers considering investment in mobile e-commerce services. Again there are large variations in usage of services in different countries, but with overall use of mobile applications relatively low.

1.2. Consumers influenced by using the online channel

To help develop effective online services, we need to understand customers’ online buyer behaviour and motivation (this topic is considered in more depth in Chapter 9, p. 492). As we saw in Figure 4.1, finding information about goods and services is a popular online activity, but each organization needs to capture data about online influence in the buying process for their own market. Managers also need to understand how the types of sites shown in Figure 2.3 influence consumers, for example are blogs, social networks or traditional media sites more trusted?We can understand significant features of online buyer behaviour from research summarized in the AOL-sponsored BrandNewWorld (2004) study which showed that:

- The Internet is a vital part of the research process with 73% of Internet users agreeing that they now spend longer researching products. The purchase process is generally now more considered and is more convoluted.

- The Internet is used at every stage of the research process from the initial scan to the more detailed comparison and final check before purchase.

- Consumers are more informed from a multiplicity of sources; price is not exclusively the primary driver.

- Online information and experience (and modified opinions about a brand or product) also translates into offline purchase. This is an important but sometimes underestimated role of e-commerce (Figure 4.3).

There is also a wide variation in influence according to type of product, so it is important to assess the role of the web in supporting buying decisions for a particular market. Understanding the potential reach of a web site and its role in influencing purchase is clearly important in setting e-marketing budgets. A different perspective on this is indicated by Figure 4.4 which shows the proportion of people who purchase offline after online research.

1.3. Motivation for use of online services

Another way for organizations to help them better understand their online customers is for marketers to develop psychographic segmentations which help explain motivation. Specialized psychodemographic profiles have been developed for web users, for example see Box 4.1 for an example of this type of segmentation applied to online purchase behaviour. Which profile do you fit?

The revised Web Motivation Inventory (WMI) identified by Rodgers et al. (2007) is a useful framework for understanding different motivations for using the web which will differ for different parts of a web session. The four motives which cut across cultures are: research (information acquisition), communication (socialization), surfing (entertainment) and shopping and these are broken down further below.

- Community

- Get to know other people

- Participate in an online chat

- Join a group.

- Entertainment

- Amuse myself

- Entertain myself

- Find information to entertain myself.

- Product trial

- Try on the latest fashions

- Experience a product

- Try out a product.

- Information

- Do research

- Get information I need

- Search for information I need.

- Transaction

- Make a purchase

- Buy things

- Purchase a product I’ve heard about.

- Game

- Play online games

- Entertain myself with Internet games

- Play online games with individuals from other countries.

- Survey

- Take a survey on a topic I care about

- Fill out an online survey

- Give my opinion on a survey.

- Downloads

- Download music

- Listen to music

- Watch online videos.

- Interaction

- Connect with my friends

- Communicate with others

- Instant message others I know.

- Search

- Get answers to specific questions

- Find information I can trust.

- Exploration

- Find interesting web pages

- Explore new sites

- Surf for fun.

- News

- Read about current events and news

- Read entertainment news.

Web advertisers and site owners can use this framework to review the suitability of facilities to meet these needs.

1.4. Purchased online

Increasing numbers of consumers are now purchasing online, but research on behaviour suggests it takes time for individuals to build up confidence to purchase. Frequency of purchase is also increased through adoption of the broadband Internet. Figure 4.4 shows that initially Internet users may restrict themselves to searching for information or using e-mail. As their confidence grows their use of the Internet for purchase is likely to increase with a move to higher-value items and more-frequent purchases. This is often coupled with the use of broadband. For this reason, there is still good potential for e-retail sales, even if the percentage of the population with access to the Internet plateaus.

You can see from Figure 4.4 that Internet users take longer to become confident to purchase more expensive and more complex products. Many of us will initially have purchased a book or DVD online, but today we buy more expensive electronic products or financial services. Figure 4.5 shows that the result is a dramatic difference in online consumer behaviour for different products according to their price and complexity. For some products such as travel and cinema and theatre tickets, the majority buy online, while for many others such as clothes and insurance fewer people purchase online. However, consistent with the trend in Figure 4.5, there is now less difference between the products than there was two or three years ago. The figure suggests that the way companies should use digital technologies for marketing their products will vary markedly according to product type. In some, such as cars and complex financial products such as mortgages, the main role of online marketing will be to support research, while for other standardized products like books and CDs there will be a dual role for the web in supporting research and enabling purchase.

The extent of adoption also varies significantly by country according to other political, economic and cultural factors. Table 4.4 shows that there is a marked difference between the amount spent online in different countries which will affect revenue projections for site in different countries. It also shows the potential for further growth in e-commerce in countries where e-commerce adoption has been lower.

Bart et al. (2005) have developed a useful, widely referenced conceptual model that links web-site and consumer characteristics, online trust, and behaviour based on 6,831 consumers across 25 sites from eight web site categories including retail, travel, financial services, portals and community sites. We have summarized the eight main drivers of trust from the study in Figure 9.4 in the section on buyer behaviour.

The model of Bart et al. (2005) and similar models are centred on a single site, but perceptions of trust are also built from external sources. The role of social media and friends, in particular in influencing sales was highlighted by this research from the European Interactive Advertising Association (2008) which rated key sources for research indicating the level of trust amongst European consumers for different online and offline information sources:

- Search engines (66%)

- Personal recommendations (64%)

- Price comparison web sites (50%)

- Web sites of well-known brands (49%)

- Newspapers/magazines (49%)

- Customer web site reviews (46%)

- Expert web site reviews (45%)

- Retailer web sites (45%)

- Sales people in shops (46%)

- Content provided by ISPs (30%).

1.5. Business demand for e-commerce services

We now turn our attention to online usage of services by business users. The B2B market is more complex than B2C in that variation in demand will occur according to different types of organization and people within the buying unit in the organization. This analysis is also important as part of the segmentation of different groups within a B2B target market. We need to profile business demand according to:

- Variation in organization characteristics

- Size of company (employees or turnover)

- Industry sector and products

- Organization type (private, public, government, not-for-profit)

- Division

- Country and region.

- Individual role

- Role and responsibility from job title, function or number of staff managed

- Role in buying decision (purchasing influence)

- Department

- Product interest

- Demographics: age, sex and possibly social group.

1.6. B2B profiles

We can profile business users of the Internet in a similar way to consumers by assessing:

- The percentage of companies with access. In the business-to-business market, Internet access levels are higher than for business-to-consumer. The European Commission (2007) study showed that over 99% of businesses in the majority of countries surveyed have Internet access (Figure 1.10). Understanding access for different members of the organizational buying unit amongst their customers is also important for marketers. Although the Internet seems to be used by many companies we also need to ask whether it reaches the right people in the buying unit. The answer is ‘not necessarily’ – access is not available to all employees. This can be an issue if marketing to particular types of staff who have shared PC access, such as healthcare professionals for example.

- Influenced online. In B2B marketing, the high level of access is consistent with a high level of using the Internet to identify suppliers. As for consumer e-commerce, the Internet is important in identifying online suppliers rather than completing the transaction online. This is particularly the case in the larger companies.

- Purchase online. The European Commission (2007) survey revealed that there is a large variation in the proportion of businesses in different countries who order online, with the figure substantially higher in countries such as Sweden and Germany in comparison to Italy and France for example. This shows the importance of understanding differences in the environment for e-commerce in different countries since this will dramatically affect the volume of leads and orders generated through e-channels. It also suggests the importance of education and persuasion in encouraging partners to migrate to these new electronic channels.

In summary, to estimate online revenue contribution to determine the amount of investment in e-business we need to research the number of connected customers, the percentage whose offline purchase is influenced online and the number who buy online.

1.7. Adoption of e-business by small and medium enterprises

The European Commission (2007) reviewed SME adoption of the Internet across Europe. The results are shown in Figure 4.6. The adoption for different e-commerce services is indexed, where 1 equates to equal access and figures less than 1 show lower levels of usage within SMEs. You can see that access and broadband usage levels are slightly lower for SMEs, but with online buying and selling significantly lower. Electronic integration of processes with other partners is very low.

Daniel et al. (2002) researched e-business adoption in UK SMEs and found a similar staged progression to those reviewed in Chapter 5. They noted four clusters – firms in the first cluster (developers) were actively developing services, but were limited at the time of research. The other clusters are: (2) communicators, those where e-mail is being used to communicate internally and within customers and suppliers, (3) web presence and (4) transactors.

The luxury of sufficient resources to focus on the planning and implementing an Internet strategy isn’t open to many small businesses and is likely to explain why they have not been such enthusiastic adopters of e-business.

A useful guide to risks and rewards of e-business for SMEs has been produced by Computer Weekly (2004). The author suggests that the level of risk and reward can be assessed through a combination of four factors.

- Revenue. This suggests comparison of the importance of online channels for direct or indirect revenue. If revenue becomes significant, then steps must be put in place to avoid outages leading to loss.

- Reputation. Again, if a significant proportion of trade is online, there is a reputational damage if the web site becomes defaced or unavailable.

- Strategic importance. How important is the web site (and electronic transactions) to you? Would there be a significant impact if it were to become unavailable?

- Regulatory compliance. If a company is processing or storing data which are subject to legislative control (e.g. customer or employee data) then the penalties or reputational damage from not providing adequate safeguards may be high if the data are compromised.

2. Privacy and trust in e-commerce

Ethical standards are personal or business practices or behaviour which are generally considered acceptable by society. A simple test is that acceptable ethics can be described as moral or just and unethical practices as immoral or unjust.

Ethical issues and the associated laws developed to control the ethical approach to Internet marketing constitute an important consideration of the Internet business environment for marketers. Privacy of consumers is a key ethical issue on which we will concentrate since many laws have been enacted and it affects all types of organization regardless of whether they have a transactional e-commerce service. A further ethical issue for which laws have been enacted in many countries is providing an accessible level of Internet services for disabled users. We will also review other laws that have been developed for managing commerce and distance-selling online. In many cases, the laws governing e-commerce are in their infancy and lag behind the applications of technology. They are also unclear, since they may not have been tested in a court of law. So, often managers have to take decisions not based solely on the law, but on whether they think a practice is acceptable business practice or whether it could be damaging to the brand if problems arise and consumers complain.

2.1. Privacy legislation

Privacy refers to a moral right of individuals to avoid intrusion into their personal affairs by third parties. Privacy of personal data such as our identities, likes and dislikes is a major concern to consumers, particularly with the dramatic increase in identity theft. This is clearly a major concern for many consumers when using e-commerce services since they believe their privacy and identity may be compromised. This is not unfounded, as Box 4.2 shows.

While identity theft is traumatic for the person who has their identity stolen, in the majority of cases, they will eventually be able to regain any lost funds through their financial services providers. This is not necessarily the case for the e-retailer. In the first part of 2008, CIFAS members reported 104,548 cases of identify theft to a potential value of £431,967,984.

2.2. Why personal data are valuable for e-businesses

While there is much natural concern amongst consumers about their online privacy, information about these consumers is very useful to marketers. Through understanding their customers’ needs, characteristics and behaviours it is possible to create more personalized, targeted communications such as e-mails and web-based personalization about related products and offers which help increase sales. How should marketers respond to this dilemma? An obvious step is to ensure that marketing activities are consistent with the latest data protection and privacy laws. Although compliance with the laws may sound straightforward, in practice different interpretations of the law are possible and since these are new laws they have not been tested in court. As a result, companies have to take their own business decision based on the business benefits of applying particular marketing practices, against the financial and reputational risks of less strict compliance.

Effective e-commerce requires a delicate balance to be struck between the benefits the individual customer will gain to their online experience through providing personal information and the amount and type of information that they are prepared for companies to hold about them.

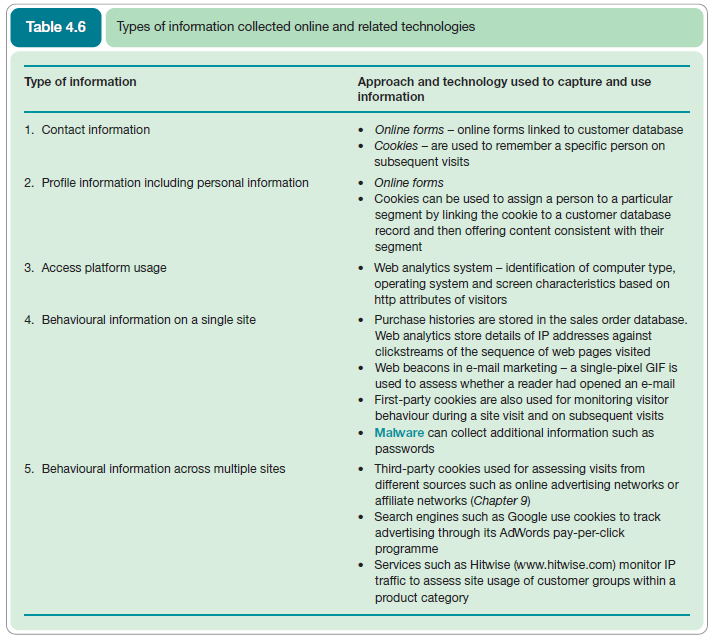

What are the main information types used by the Internet marketer which are governed by ethics and legislation? The information needs are:

- Contact information. This is the name, postal address, e-mail address and, for B2B companies, web site address.

- Profile information. This is information about a customer’s characteristics that can be used for segmentation. They include age, sex and social group for consumers, and company characteristics and individual role for business customers. The specific types of information and how they are used is referenced in Chapters 2 and The willingness of consumers to give this information and the effectiveness of incentives have been researched in Australian consumers by Ward et al. (2005). They found that consumers are willing to give nonfinancial data if there is an appropriate incentive.

- Platform usage information. Through web analytics systems it is possible to collect information on type of computer, browser and screen resolution used by site users (see Chapter 7). For example, Figure 4.7shows detail collected by a widget installed on Dave Chaffey.com. As well as the platform used, the search term referred from Google is shown. Many Internet users will not realize that their visits are tracked in this way on virtually all sites, but the important point to know is that it is not possible to identify an individual unless they have agreed to give information through a web form and their profile information is then collected which is the situation when someone subscribes to an e-newsletter or purchases a product online.

- Behavioural information (on a single site). This is purchase history, but also includes the whole buying process. Web analytics (Chapter 12) can be used to assess the web and e-mail content accessed by individuals.

- Behavioural information (across multiple sites). This can potentially show how a user accesses multiple sites and responds to ads across sites. Typically these data are collected and used using an anonymous profile based on cookie or IP addresses which is not related to an individual.

Table 4.6 summarizes how these different types of customer information are collected and used through technology. The main issue to be considered by the marketer is disclosure of the types of information collection and tracking data used. The first two types of information in the table are usually readily explained through a privacy statement at the point of data collection and as we will see this is usually a legal requirement. However, with the other types of information, users would only know they were being tracked if they have cookie monitoring software installed or if they seek out the privacy statement of a publisher which offers advertising.

Ethical issues concerned with personal information ownership have been usefully summarized by Mason (1986) into four areas:

- Privacy – what information is held about the individual?

- Accuracy – is it correct?

- Property – who owns it and how can ownership be transferred?

- Accessibility – who is allowed to access this information, and under which conditions?

Fletcher (2001) provides an alternative perspective, raising these issues of concern for both the individual and the marketer:

- Transparency – who is collecting what information and how do they disclose the collection of data and how it will be used?

- Security -how is information protected once it has been collected by a company?

- Liability -who is responsible if data are abused?

All of these issues arise in the next section which reviews actions marketers should take to achieve privacy and trust.

Data protection legislation is enacted to protect the individual, to protect their privacy and to prevent misuse of their personal data. Indeed, the first article of the European Union directive 95/46/EC (see http://ec.europa.eu/justice_home/fsj/privacy/) on which legislation in individual European countries is based, specifically refers to personal data. It says:

Member states shall protect the fundamental rights and freedoms of natural persons [i.e. a named individual at home or at work], and in particular their right to privacy with respect to the processing of personal data.

In the UK, the enactment of the European legislation is the Data Protection Act 1984, 1998 (DPA). It is managed by the ‘Information Commissioner’ and summarized at www.informationcommissioner.gov.uk. This law is typical of what has evolved in many countries to help protect personal information. Any company that holds personal data on computers or on file about customers or employees must be registered with the data protection registrar (although there are some exceptions which may exclude small businesses). This process is known as notification.

The guidelines on the eight data protection principles are produced by legal requirements of the 1998 UK Data Protection Act, on which this overview is based. These principles state that personal data should be:

- Fairly and lawfully processed.

In full: ‘Personal data shall be processed fairly and lawfully and, in particular, shall not be processed unless – at least one of the conditions in Schedule 2 is met; and in the case of sensitive personal data, at least one of the conditions in Schedule 3 is also met’

The Information Commissioner has produced a ‘fair processing code’ which suggests how an organization needs to achieve ‘fair and lawful processing’ under the details of schedules 2 and 3 of the Act. This requires:

-

- Appointment of a data controller who is a person with defined responsibility for data protection within a company.

- Clear details in communications such as on a web site or direct mail of how a ‘data subject’ can contact the data controller or a representative.

- Before data processing ‘the data subject has given his consent’ or the processing must be necessary either for a ‘contract to which the data subject is a party’ (for example as part of a sale of a product) or because it is required by other laws. Consent is defined in the published guidelines as ‘any freely given specific and informed indication of his wishes by which the data subject signifies his agreement to personal data relating to him being processed’.

- Sensitive personal data require particular care, these include

- the racial or ethnic origin of the data subject;

- political opinions;

- religious beliefs or other beliefs of a similar nature;

- membership of a trade union;

- physical or mental health or condition;

- sexual life;

- the commission or alleged commission or proceedings of any offence.

- No other laws must be broken in processing the data.

- Processed for limited purposes.

In full: ‘Personal data shall be obtained only for one or more specified and lawful purposes, and shall not be further processed in any manner incompatible with that purpose or those purposes’ This implies that the organization must make it clear why and how the data will be processed at the point of collection. For example, an organization has to explain how your data will be used if you provide your details on a web site when entering a prize draw. You would also have to agree (give consent) for further communications from the company.

Figure 4.8 suggests some of the issues that should be considered when a data subject is informed of how the data will be used. Important issues are:

-

- Whether future communications will be sent to the individual (explicit consent is required for this in online channels, which is clarified by the related Privacy and Electronic Communications Regulation Act which is referred to below);

- Whether the data will be passed on to third parties (again explicit consent is required);

- How long the data will be kept for.

- Adequate, relevant and not excessive.

In full: ‘Personal data shall be adequate, relevant and not excessive in relation to the purpose or purposes for which they are processed ’

This specifies that the minimum necessary amount of data is requested for processing. There is difficulty in reconciling this provision between the needs of the individual and the needs of the company. The more details that an organization has about a customer, the better they can understand that customer and so develop products and marketing communications specific to that customer which they are more likely to respond to.

- Accurate.

In full: ‘Personal data shall be accurate and, where necessary, kept up to date’

It is clearly also in the interest of an organization in an ongoing relationship with a partner that the data is kept accurate and up-to-date. The guidelines on the Act suggest that additional steps should be taken to check data are accurate, in case they are in error, for example due to mis-keying by the data subject or the organization or for some other reason. Inaccurate data is defined in the guidelines as: ‘incorrect or misleading as to any matter of fact’.

The guidelines go on to discuss the importance of keeping information up-to-date. This is only necessary where there is an ongoing relationship and the rights of the individual maybe affected if they are not up-to-date. This implies, for example that a credit-checking agency should keep credit scores up-to-date.

- Not kept longer than necessary.

In full: ‘Personal data processed for any purpose or purposes shall not be kept for longer than is necessary for that purpose or those purposes’

The guidelines state: ‘To comply with this Principle, data controllers will need to review their personal data regularly and to delete the information which is no longer required for their purposes’

It might be in a company’s interests to ‘clean data’ so that records that are not relevant are archived or deleted, for example if a customer has not purchased for ten years. However, there is the possibility that the customer may still buy again, in which case the information would be useful.

If a relationship between the organization and the data subject ends, then data should be deleted. This will be clear in some instances, for example when an employee leaves a company their personal data should be deleted. With a consumer who has purchased products from a company this is less clear since frequency of purchase will vary, for example, a car manufacturer could justifiably hold data for several years.

- Processed in accordance with the data subject’s rights.

In full: ‘Personal data shall be processed in accordance with the rights of data subjects under this Act’

One aspect of the data subject’s rights is the option to request a copy of their personal data from an organization; this is known as a ‘subject access request’. For payment of a small fee such as £10 or £30, an individual can request information which must be supplied by the organization within 40 days. This includes all information on paper files and on computer. If you requested this information from your bank there might be several boxes of transactions!

Other aspects of a data subject’s rights which the law upholds are designed to prevent or control processing which:

-

- causes damage or distress (for example repeatedly sending mailshots to someone who has died);

- is used for direct marketing (for example, in the UK consumers can subscribe to the mail, e-mail or telephone preference service to avoid unsolicited mailings, e-mails or phone calls). This invaluable service is provided by the Direct Marketing Association (dmaconsumers.org). If you subscribe to these services organizations must check against these ‘exclusion lists’ before contacting you. If they don’t, and some don’t, they are breaking the law.

- is used for automatic decision taking – automated credit checks, for example, may result in unjust decisions on taking a loan – these can be investigated if you feel the decision is unfair.

- Secure.

In full: ‘Appropriate technical and organizational measures shall be taken against unauthorised or unlawful processing of personal data and against accidental loss or destruction of, or damage to, personal data’

This guideline places a legal imperative on organizations to prevent unauthorized internal or external access to information and also its modification or destruction. Of course, most organizations would want to do this anyway since the information has value to their organization and the reputational damage of losing customer information or being subject to a hack attack can be severe. For example, in late 2006, online clothing retail group TJX Inc (owner of TK Maxx) was hacked, resulting in loss of credit card details of over 45 million customer details in the US and Europe. TJX later said in its security filing that its potential liability (loss) from the computer intrusion(s) was $118 million.

Techniques for managing data security are discussed in Chapter 11.

Of course, the cost of security measures will vary according to the level of security required. The Act allows for this through this provision:

-

- Taking into account the state of technological development at any time and the cost of implementing any measures, the measures must ensure a level of security appropriate to:

- the harm that might result from a breach of security; and (b) the nature of the data to be protected. (ii) The data controller must take reasonable steps to ensure the reliability of staff having access to the personal data.

- Not transferred to countries without adequate protection.

In full: ‘Personal data shall not be transferred to a country or territory outside the European Economic Area, unless that country or territory ensures an adequate level of protection of the rights and freedoms of data subjects in relation to the processing of personal data.’

Transfer of data beyond Europe is likely for multinational companies. This principle prevents export of data to countries that do not have sound data processing laws. If the transfer is required in concluding a sale or contract or if the data subject agrees to it, then transfer is legal. Data transfer with the US is possible through companies registered through the Safe Harbor scheme (www.export.gov/safeharbor).

2.3. Anti-spam legislation

Laws have been enacted in different countries to protect individual privacy and with the intention of reducing spam or unsolicited commercial e-mail (UCE). Originally, the best-known ‘spam’ was tinned meat (a contraction of‘spiced ham’), but a modern version of this acronym is ‘ Sending Persistent Annoying e-Maif. Spammers rely on sending out millions of e-mails in the hope that even if there is only a 0.01% response they may make some money, if not get rich.

Anti-spam laws do not mean that e-mail cannot be used as a marketing tool. As explained below, permission-based e-mail marketing based on consent or opt-in by customers and the option to un-subscribe or opt out is the key to successful e-mail marketing. But if companies ignore or misinterpret the law, they may regret it. In 2008, clothing brand Timberland had to pay $7 million to settle an SMS spam lawsuit.

Before starting an e-mail dialogue with customers, according to law in Europe, America and many countries in the Asia-Pacific region, companies must ask customers to provide their e-mail address and then give them the option of ‘opting into’ further communications. E-mail lists can also be purchased where customers have opted in to receive e-mail.

Legal opt-in e-mail addresses and customer profile information are available for purchase or rental from a database traditionally known by marketers as a ‘cold list’, so-called because the company that purchases the data from a third party does not know you. Your name will also potentially be stored on an opt-in house list within companies you have purchased from where you have given your consent to be contacted by the company or given additional consent to be contacted by its partners.

2.4. Regulations on privacy and electronic communications

While the Data Protection Directive 95/46 and Data Protection Act afford a reasonable level of protection for consumers, they were quickly superseded by advances in technology and the rapid growth in spam. As a result, in 2002 the European Union passed the Act ‘2002/58/EC Directive on Privacy and Electronic Communications’ to complement previous data protection law (see Box 4.3). This Act is significant from an information technology perspective since it applies specifically to electronic communications such as e-mail and the monitoring of web sites using technologies such as cookies.

2.5. Worldwide regulations on privacy and electronic communications

In the USA, there is a privacy initiative aimed at education of consumers and business (www.ftc.gov/privacy), but legislation is limited other than for e-mail marketing. In the US in January 2004, a new federal law known as the CAN-SPAM Act (www.ftc.gov/spam) was introduced to assist in the control of unsolicited e-mail. CAN SPAM stands for ‘Controlling the Assault of Non-Solicited Pornography and Marketing’ (an ironic juxtaposition between pornography and marketing). This harmonized separate laws in different US states, but was less strict than in some states such as California. The Act requires unsolicited commercial e-mail messages to be labelled (though not by a standard method) and to include opt-out instructions and the sender’s physical address. It prohibits the use of deceptive subject lines and false headers in such messages. Anti-spam legislation in other countries can be accessed:

- Australia enacted a spam Act in 2003 (privacy.gov.au)

- Canada has a privacy Act (privcom.gc.ca)

- New Zealand Privacy Commissioner (privacy.org.nz)

- Summary of all countries (privacyinternational.org and www.spamlaws.com).

While such laws are clearly in consumers’ interests, some companies see the practice as restrictive. In 2002, ten companies including IBM, Oracle and VeriSign, who referred to themselves as the ‘Global Privacy Alliance (GPA)’, lobbied the EU saying that it put too much emphasis on the protection of individuals’ privacy, and not enough on ensuring the free flow of information between companies! More positively, the Online Privacy Alliance (www.privacyalliance.org) is a‘group of more than 30 global corporations and associations who have come together to introduce and promote business-wide actions that create an environment of trust and foster the protection of individuals’ privacy online’.

2.6. Viral e-mail marketing

One widespread business practice that is not covered explicitly in the PECR law is ‘viral marketing’. The network of people referred to in the definition is more powerful in an online context where e-mail is used to transmit the virus – rather like a cold or flu virus. The combination of the viral offer and the transmission medium is sometimes referred to as the ‘viral agent’. Different types of viral marketing are reviewed in Chapter 9, p. 524.

There are several initiatives that are being taken by industry groups to reassure web users about threats to their personal information. The first of these is TRUSTe (www.truste.org), sponsored by IBM and with sites validated by PricewaterhouseCoopers and KPMG. The validators will audit the site to check each site’s privacy statement to see whether it is valid. For example, a privacy statement will describe:

- how a site collects information;

- how the information is used;

- who the information is shared with;

- how users can access and correct information;

- how users can decide to deactivate themselves from the site or withhold information from third parties.

A UK accreditation initiative aimed at reassurance coordinated by the Internet Media in Retail Group is ISIS, a trade group for e-retailers (Internet Shopping Is Safe) (www.imrg.org/ISIS). Another initiative, aimed at education is GetSafeOnline (www.getsafeonline.org) which is a site created by government and business to educate consumers to help them understand and manage their online privacy and security.

Government initiatives will also define best practice in this area and may introduce laws to ensure guidelines are followed. In the UK, the Data Protection Act covers some of these issues and the 1999 European Data Protection Act also has draft laws to help maintain personal privacy on the Internet.

We conclude this section on privacy legislation with a checklist summary of the practical steps that are required to audit a company’s compliance with data protection and privacy legislation. Companies should:

- Follow privacy and consumer protection guidelines and laws in all local markets. Use local privacy and security certification where available.

- Inform the user, before asking for information:

- who the company is;

- what personal data are collected, processed and stored;

- what is the purpose of collection.

- Ask for consent for collecting sensitive personal data, and it is good practice to ask before collecting any type of data.

- Reassure customers by providing clear and effective privacy statements and explaining the purpose of data collection.

- Let individuals know when ‘cookies’ or other covert software are used to collect information about them.

- Never collect or retain personal data unless it is strictly necessary for the organization’s purposes. For example, a person’s name and full address should not be required to provide an online quotation. If extra information is required for marketing purposes this should be made clear and the provision of such information should be optional.

- Amend incorrect data when informed and tell others. Enable correction on-site.

- Only use data for marketing (by the company, or third parties) when a user has been informed this is the case and has agreed to this. (This is opt-in.)

- Provide the option for customers to stop receiving information. (This is opt-out.)

- Use appropriate security technology to protect the customer information on your site.

3. Other e-commerce legislation

Sparrow (2000) identified eight areas of law which need to concern online marketers. Although laws have been refined since that time, this is still a useful framework for considering the laws to which digital marketers are subject.

3.1. Marketing your e-commerce business

At the time of writing, Sparrow used this category to refer to purchasing a domain name for its web site. There are now other legal constraints that also fall under this category.

A Domain name registration

Most companies are likely to own several domains, perhaps for different product lines, countries or for specific marketing campaigns. Domain name disputes can arise when an individual or company has registered a domain name which another company claims they have the right to. This is sometimes referred to as ‘cybersquatting’ and was covered in Chapter 3.

A related issue is brand and trademark protection. Online brand reputation management and alerting software tools offer real-time alerts when comments or mentions about a brand are posted online in different locations including blogs and social networks. Some basic tools are available including:

- Googlealert (googlealert.com) and Google Alerts (www.google.com/alerts) which will alert companies when any new pages appear that contain a search phrase such as your company or brand names.

- Blog Pulse (blogpulse.com) gives trends and listings of any phrase (see example in Figure 4.9) and individual postings can be viewed

- Paid tools (see listing at davechaffey.com/online-reputation-management-tools)

B Using competitor names and trademarks in meta-tags (for search engine optimization)

Meta-tags, which are part of the HTML code of a site, are used to market web sites by enabling them to appear more prominently in search engines as part of search engine optimization (SEO) (see Chapter 9). Some companies have tried putting the name of a competitor company name within the meta-tags. This is not legal since case law has found against companies that have used this approach. A further issue of marketing-related law is privacy law for e-mail marketing which was considered in the previous section.

C Using competitor names and trademarks in pay-per-click advertising

A similar approach can potentially be used in pay-per-click marketing (see Chapter 9) to advertise on competitors’ names and trademarks. For example, if a search user types ‘Dell laptop’ can an advertiser bid to place an ad offering an ‘HP laptop’? There is less case law in this area and differing findings have occurred in the US and France (such advertising is not permitted in France). One example of the types of issues that can arise is highlighted in Box 4.5.

D Accessibility law

Laws relating to discriminating against disabled users who may find it more difficult to use web sites because of audio, visual or motor impairment are known as accessibility legislation. This is often contained within disability and discrimination acts. In the UK, the relevant act is the Disability and Discrimination Act 1995.

Web accessibility refers to enabling all users of a web site to interact with it regardless of disabilities they may have or the web browser or platform they are using to access the site. The visually impaired or blind are the main audience that designing an accessible web site can help. Coverage of the requirements that accessibility places on web design are covered in Chapter 7.

Internet standards organizations such as the World Wide Web Consortium have been active in promoting guidelines for web accessibility (www.w3.org/WAI). This site describes such common accessibility problems as:

images without alternative text; lack of alternative text for imagemap hot-spots; misleading use of structural elements on pages; uncaptioned audio or undescribed video; lack of alternative information for users who cannot access frames or scripts; tables that are difficult to decipher when linearized; or sites with poor color contrast.

A tool provided to assess the WWW standards is BOBBY (http://bobby.cast.org).

A case that highlights the need for web site accessibility is that brought by Bruce Maguire, a blind Internet user who uses a refreshable Braille display, against the Sydney Organizing Committee for the Olympic Games in 2000. Maguire successfully demonstrated deficiencies in the site which prevented him using it adequately, which were not successfully remedied. He was protected under the 1992 Australian Disability Discrimination Act and the defendant was ordered to pay AU$20,000. This was the first case brought in the world, and it showed organizations in all countries that they could be guilty of discrimination if they did not audit their sites against accessibility guidelines since many countries such as the USA and the UK have similar discrimination acts. Such acts are now being amended in many countries to specifically refer to online discrimination.

3.2. Forming an electronic contract (contract law and distance-selling law)

We will look at two aspects of forming an electronic contract: the country of origin principle and distance selling laws.

Country of origin principle

The contract formed between a buyer and a seller on a web site will be subject to the laws of a particular country. In Europe, many such laws are specified at the regional (European Union) level, but are interpreted differently in different countries. This raises the issue of the jurisdiction in which law applies – is it that for the buyer, for example located in Germany, or the seller (merchant), whose site is based in France? Although this has been unclear, in 2002 attempts were made by the EU to adopt the ‘country of origin principle’. This means that the law for the contract will be that where the merchant is located. The Out-Law site produced by lawyers Pinsent Mason gives more information on jurisdiction (www.out-law.com/page-479).

Distance-selling law

Sparrow (2000) advises different forms of disclaimers to protect the retailer. For example, if a retailer made an error with the price or the product details were in error, then the retailer is not bound to honour a contract, since it was only displaying the products as ‘an invitation to treat’ not a fixed offer.

A well-known case was when an e-retailer offered televisions for £2.99 due to an error in pricing a £299 product. Numerous purchases were made, but the e-retailer claimed that a contract had not been established simply by accepting the online order, although the customers did not see it that way! Unfortunately, no legal precedent was established in this case since the case did not come to trial.

Disclaimers can also be used to limit liability if the web site service causes a problem for the user, such as a financial loss resulting from an action based on erroneous content. Furthermore, Sparrow suggests that terms and conditions should be developed to refer to issues such as timing of delivery and damage or loss of goods.

The distance-selling directive also has a bearing on e-commerce contracts in the European Union. It was originally developed to protect people using mail-order (by post or phone). The main requirements, which are consistent with what most reputable e-retailers would do anyway, are that e-commerce sites must contain easily accessible content which clearly states:

- The company’s identity including address;

- The main features of the goods or services;

- Prices information, including tax and, if appropriate, delivery costs;

- The period for which the offer or price remains valid;

- Payment, delivery and fulfilment performance arrangements;

- Right of the consumer to withdraw, i.e. cancellation terms;

- The minimum duration of the contract and whether the contract for the supply of products or services is to be permanent or recurrent, if appropriate;

- Whether an equivalent product or service might be substituted, and confirmation as to whether the seller pays the return costs in this event.

After the contract has been entered into, the supplier is required to provide written confirmation of the information provided. An e-mail confirmation is now legally binding provided both parties have agreed that e-mail is an acceptable form for the contract. It is always advisable to obtain an electronic signature to confirm that both parties have agreed the contract, and this is especially valuable in the event of a dispute. The default position for services is that there is no cancellation right once services begin.

The Out-Law site produced by lawyers Pinsent Mason gives more information on distance selling (www.out-law.com/page-430).

3.3. Making and accepting payment

For transactional e-commerce sites, the relevant laws are those referring to liability between a credit card issuer, the merchant and the buyer. Merchants need to be aware of their liability for different situations such as the customer making a fraudulent transaction.

3.4. Authenticating contracts concluded over the Internet

‘Authentication’ refers to establishing the identity of the purchaser. For example, to help prove a credit card owner is the valid owner, many sites now ask for a 3-digit authentication code which is separate from the credit card number. This helps reduce the risk of someone buying fraudulently who has, for instance, found a credit card number from a traditional shopping purchase. Using digital signatures is another method of helping to prove the identity of purchasers (and merchants).

3.5. E-mail risks

One of the main risks with e-mail is infringing an individual’s privacy. Specific laws have been developed in many countries to reduce the volume of unsolicited commercial e-mail or spam, as explained in the previous section on privacy.

A further issue with e-mail is defamation. This is where someone makes a statement that is potentially damaging to an individual or a company. A well known example from 2000 involved a statement made on the Norwich Union Healthcare internal e-mail system in England which was defamatory towards a rival company, WPA. The statement falsely alleged that WPA was under investigation and that regulators had forced them to stop accepting new business. The posting was published on the internal e-mail system to various members of Norwich Union Healthcare staff. Although this was only on an internal system, it was not contained and became more widespread. WPA sued for libel and the case was settled in an out-of-court settlement when Norwich Union paid £415,000 to WPA. Such cases are relatively rare.

3.6. Protecting intellectual property (IP)

Intellectual property rights (IPR) protect designs, ideas and inventions and includes content and services developed for e-commerce sites. Closely related is copyright law which is designed to protect authors, producers, broadcasters and performers through ensuring they see some returns from their works every time they are experienced. The European Directive of Copyright (2001/29/EC) came into force in many countries in 2003. This is a significant update to the law which covers new technologies and approaches such as streaming a broadcast via the Internet.

3.7. IP can be misappropriated in two senses online.

First, an organization’s IP may be misappropriated and you need to protect against this. For example, it is relatively easy to copy web content and republish on another site, and this practice is not unknown amongst smaller businesses. Reputation management services can be used to assess how an organization’s content, logos and trademarks are being used on other web sites. Tools such as Copyscape (www.copyscape.com) can be used to identify infringement of content where it is ‘scraped’ off other sites using ‘screenscrapers’.

Secondly, an organization may misappropriate content inadvertently. Some employees may infringe copyright if they are not aware of the law. Additionally, some methods of designing transactional web sites have been patented. For example, Amazon has patented its ‘One-click’ purchasing option, which is why you do not see this labelling and process on other sites.

3.8. Advertising on the Internet

Advertising standards that are enforced by independent agencies such as the UK’s Advertising Standards Authority Code also apply in the Internet environment (although they are traditionally less strongly policed, leading to more ‘edgy’ creative executions online which are intended to have a viral effect).

The Out-Law site produced by lawyers Pinsent Mason gives more information on online advertising law www.out-law.com/page-5604)

3.9. Data protection

Data protection has been referred to in depth in the previous section.

Source: Dave Chaffey (2010), E-Business and E-Commerce Management: Strategy, Implementation and Practice, Prentice Hall (4th Edition).

Your means of describing all in this post is really nice, every one be able to effortlessly be

aware of it, Thanks a lot.

What’s up, just wanted to tell you, I loved this blog post.

It was helpful. Keep on posting!