As explained at the start of the chapter, e-business infrastructure comprises the hardware, software, content and data used to deliver e-business services to employees, customers and partners. In this part of the chapter we look at the management of e-business infrastructure by reviewing different perspectives on the infrastructure. These are:

- Hardware and systems software infrastructure. This refers mainly to the hardware and network infrastructure discussed in the previous sections. It includes the provision of clients, servers, network services and also systems software such as operating systems and browsers (Layers II, III and IV in Figure 3.1).

- Applications infrastructure. This refers to the applications software used to deliver services to employees, customers and other partners (Layer I in Figure 3.1).

A further perspective is the management of data and content (Layer V in Figure 3.1) which is reviewed in more detail in the third part of this book.

To illustrate the importance and challenges of maintaining an adequate infrastructure, read the mini case study about the microblogging service Twitter. Twitter is a fascinating case of the challenges of monetizing an online service and delivering adequate services levels with a limited budget and a small team. This case study shows some of the successes and challenges for the start-up e-business.

1. Managing hardware and systems software infrastructure

Management of the technology infrastructure requires decisions on Layers II, III and IV in Figure 3.1.

1.1. Layer II – Systems software

The key management decision is standardization throughout the organization. Standardization leads to reduced numbers of contacts for support and maintenance and can reduce purchase prices through multi-user licences. Systems software choices occur for the client, server and network. On the client computers, the decision will be which browser software to

standardize on, for example Microsoft Explorer or an open-source alternative. Standardized plug-ins such as Adobe Acrobat to access .pdf files should also be installed across the organization. The systems software for the client will also be decided on; this will probably be a variant of Microsoft Windows, but open-source alternatives such as Linux may also be considered. When considering systems software for the server, it should be remembered that there may be many servers in the global organization, both for the Internet and intranets. Using standardized web-server software such as Apache will help maintenance. Networking software will also be decided on; this could be Microsoft-sourced or from other suppliers such as Sun Microsystems or Novell.

1.2. Layer III – Transport or network

Decisions on the network will be based on the internal company network, which for the e-business will be an intranet, and for the external network either an extranet or VPN (p. 177) or links to the public Internet. The main management decision is whether internal or external network management will be performed by the company or outsourced to a third party. Outsourcing of network management is common. Standardized hardware is also needed to connect clients to the Internet, for example, a modem card or external modem in home PCs or a network interface card (NIC) to connect to the company (local-area) network for business computers.

1.3. Layer IV – Storage

The decision on storage is similar to that for the transport layer. Storage can be managed internally or externally. This is not an either-or choice. For example, intranet and extranet are commonly managed internally while Internet storage such as the corporate web site is commonly managed externally or at an application service provider (p. 168). However, intranets and extranets can also be managed externally.

We will now consider decisions involving third-party service providers of the hardware and systems software infrastructure.

2. Managing Internet service and hosting providers

Service providers who provide access to the Internet for consumers or businesses are usually referred to as ‘ISPs’ or ‘Internet service providers’. ISPs may also host the web sites which publish a company’s web site content. But many organizations will turn to a separate hosting provider to manage the company’s web site and other e-business services accessed by customers and partners such as extranets, so it is important to select an appropriate hosting provider.

2.1. ISP connection methods

Figure 3.2 shows the way in which companies or home users connect to the Internet. The diagram is greatly simplified in that there are several tiers of ISPs. A user may connect to one ISP which will then transfer the request to another ISP which is connected to the main Internet backbone.

High-speed broadband is now the dominant home access method rather than the previously popular dial-up connection.

However, companies should remember that there are significant numbers of Internet users who have the slower dial-up access which they support through their web sites. Ofcom (2008) reported that the proportion of homes taking broadband services grew to 58% by Q1 2008, a rise of six percentage points on a year earlier. However, the rate of growth is slowing, following increases of 11% and 10% in the previous two years.

Broadband uses a technology known as ADSL or asymmetric digital subscriber line, which means that the traditional phone line can be used for digital data transfer. It is asym-metric since download speeds are typically higher than upload speeds. Small and medium businesses can also benefit from faster continuous access than was previously possible.

The higher speeds available through broadband together with a continuous ‘always on’ connection that has already transformed use of the Internet. Information access is more rapid and it becomes more practical to access richer content such as digital video. The increased speed increases usage of the Internet.

2.2. Issues in management of ISP and hosting relationships

The primary issue for businesses in managing ISPs and hosting providers is to ensure a satisfactory service quality at a reasonable price. As the customers and partners of organizations become more dependent on their web services, it is important that downtime be minimized. But surprisingly in 2008 severe problems of downtime can occur as shown in Box 3.5 and the consequences of these need to be avoided or managed.

2.3. Speed of access

A site or e-business service fails if it fails to deliver an acceptable download speed for users. In the broadband world this is still important as e-business applications become more complex and sites integrate more rich media such as audio and video. But what is acceptable?

Research supported by Akamai (2006) suggested that content needs to load within 4 seconds, otherwise site experience suffers. The research also showed, however, that high product price and shipping costs and problems with shipping were considered more important than speed. However, for sites perceived to have poor performance, many shoppers said they would be be likely to visit the site again (64%) or buy from the e-retailer (62%).

Speed of access of a customer, employee or partner to services on an e-business server is determined by both the speed of server and the speed of the network connection to the server. The speed of the site governs how fast the response is to a request for information from the end-user. This will be dependent on the speed of the server machine on which the web site is hosted and how quickly the server processes the information. If there are only a small number of users accessing information on the server, then there will not be a noticeable delay on requests for pages. If, however, there are thousands of users requesting information at the same time then there may be a delay and it is important that the combination of web server software and hardware can cope. Web server software will not greatly affect the speed at which requests are answered. The speed of the server is mainly controlled by the amount of primary storage (for example, 1024 Mb RAM is faster than 512 Mb RAM) and the speed of the magnetic storage (hard disk). Many of the search-engine web sites now store all their index data in RAM since this is faster than reading data from the hard disk. Companies will pay ISPs according to the capabilities of the server.

As an indication of the factors that affect performance, the DaveChaffey.com website has a shared plan from the hosting provider which offers:

- 2400 GB bandwidth

- 200 MB application memory

- 60 GB disk space (this is the hosting capacity which doesn’t affect performance).

An important aspect of hosting selection is whether the server is dedicated or shared (colocated). Clearly, if content on a server is shared with other sites hosted on the same server then performance and downtime will be affected by demand loads on these other sites. But a dedicated server package can cost 5 to 10 times the amount of a shared plan, so many small and medium businesses are better advised to adopt a shared plan, but take steps to minimize the risks with other sites going down.

For high-traffic sites, servers may be located across several computers with many processors to spread the demand load. New distributed methods of hosting content, summarized by Spinrad (1999), have been introduced to improve the speed of serving web pages for very large corporate sites. These methods involve distributing content on servers around the globe, and the most widely used service is Akamai (www.akamai.com). These are used by companies such as Yahoo!, Apple and other ‘hot-spot’ sites likely to receive many hits.

The speed is also governed by the speed of the network connection, commonly referred to as the network ‘bandwidth’. The bandwidth of a web site’s connection to the Internet and the bandwidth of the customer’s connection to the Internet will affect the speed with which web pages and associated graphics load onto the customer’s PC. The term is so called because of the width of range of electromagnetic frequencies an analogue or digital signal occupies for a given transmission medium.

As described in Box 3.7, bandwidth gives an indication of the speed at which data can be transferred from a web server along a particular medium such as a network cable or phone line. In simple terms bandwidth can be thought of as the size of a pipe along which information flows. The higher the bandwidth, the greater the diameter of the pipe, and the faster information is delivered to the user. Many ISPs have bandwidth caps, even on ‘unlimited’ Internet access plans for users who consume high volumes of bandwidth for video streams for example.

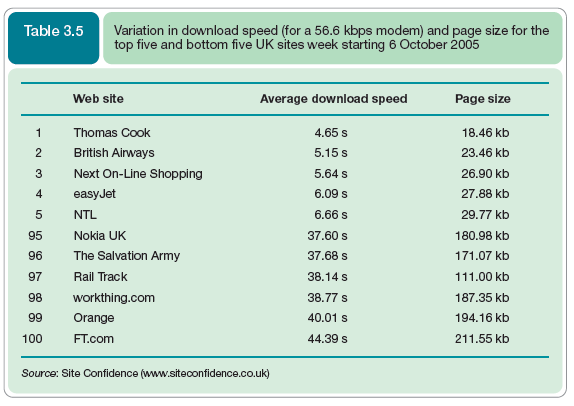

Table 3.5 shows that the top five sites with the lowest download speeds tend to have a much lower page size or ‘weight’ compared with the slower sites from 95 to 100. This shows that the performance of a site is not simply dependent on the hosting with the ISP, but depends on how the site is designed. Such a system is known as a content management system (CMS). As explained in more detail in Chapter 12, a CMS is a means of managing the updating and publication of information on any web site, whether intranet, extranet or Internet. The CMS used can also make a big difference. However, viewing these slower sites over a broadband connection shows that this is perhaps less of an issue than in the days when the majority, rather than the minority, were dial-up Internet users.

A major factor for a company to consider when choosing an ISP is whether the server is dedicated to one company or whether content from several companies is located on the same server. A dedicated server is best, but it will attract a premium price.

2.4. Availability

The availability of a web site is an indication of how easy it is for a user to connect to it. In theory this figure should be 100 per cent, but sometimes, for technical reasons such as failures in the server hardware or upgrades to software, the figure can drop substantially below this. Box 3.8 illustrates some of the potential problems and how companies can evaluate and address them.

2.5. Service-level agreements

To ensure the best speed and availability a company should check the service-level agreements (SLAs) carefully when outsourcing web site hosting services. The SLA will define confirmed standards of availability and performance measured in terms of the latency or network delay when information is passed from one point to the next (such as London to New York). The SLA also includes notification to the customer detailing when the web service becomes unavailable with reasons why and estimates of when the service will be restored. Further information on SLAs is available at www.uk.uu.net/support/sla/.

2.6. Security

Security is another important issue in service quality. How to control security was referred to in the earlier section on firewalls and is considered in detail in the Focus on security design (Chapter 11, p. 652).

3. Managing employee access to the Internet and e-mail

This is covered in Chapter 11 in the Focus on e-business security section.

4. Managing e-business applications infrastructure

Management of the e-business applications infrastructure concerns delivering the right applications to all users of e-business services. The issue involved is one that has long been a concern of IS managers, namely to deliver access to integrated applications and data that are available across the whole company. Traditionally businesses have developed applications silos or islands of information, as depicted in Figure 3.17(a). This shows that these silos may develop at three different levels: (1) there maybe different technology architectures used in different functional areas, giving rise to the problems discussed in the previous section, (2) there will also be different applications and separate databases in different areas and (3) processes or activities followed in the different functional areas may also be different.

These applications silos are often a result of decentralization or poorly controlled investment in information systems, with different departmental managers selecting different systems from different vendors. This is inefficient in that it will often cost more to purchase applications from separate vendors, and also it will be more costly to support and upgrade. Even worse is that such a fragmented approach stifles decision making and leads to isolation between functional units. An operational example of the problems this may cause is if a customer phones a B2B company for the status of a bespoke item they have ordered, where the person in customer support may have access to their personal details but not the status of their job, which is stored on a separate information system in the manufacturing unit. Problems can also occur at tactical and strategic levels. For example, if a company is trying to analyse the financial contribution of customers, perhaps to calculate lifetime values, some information about customers’ purchases may be stored in a marketing information system, while the payments data will be stored in a separate system within the finance department. It may prove difficult or impossible to reconcile these different data sets.

To avoid the problems of a fragmented applications infrastructure, companies attempted throughout the 1990s to achieve the more integrated position shown in Figure 3.17(b). Here the technology architecture, applications, data architecture and process architecture are uniform and integrated across the organization. To achieve this many companies turned to enterprise resource planning (ERP) vendors such as SAP, Baan, PeopleSoft and Oracle.

The approach of integrating different applications through ERP is entirely consistent with the principle of e-business, since e-business applications must facilitate the integration of the whole supply chain and value chain. It is noteworthy that many of the ERP vendors such as SAP have repositioned themselves as suppliers of e-business solutions! The difficulty for those managing e-business infrastructure is that there is not, and probably never can be, a single solution of components from a single supplier. For example, to gain competitive edge, companies may need to turn to solutions from innovators who, for example, support new channels such as WAP, or provide knowledge management solutions or sales management solutions. If these are not available from their favoured current supplier, do they wait until these components become available or do they attempt to integrate new software into the application? Thus managers are faced with a precarious balancing act between standardization or core product and integrating innovative systems where applicable. Figure 3.18 (illustrates this dilemma. It shows how different types of applications tend to have strengths in different areas. ERP systems were originally focused on achieving integration at the operational level of an organization. Solutions for other applications such as business intelligence in the form of data warehousing and data mining tended to focus on tactical decision making based on accessing the operational data from within ERP systems. Knowledge management software (Chapter 10) also tends to cut across different levels of management. Figure 3.18 only shows some types of applications, but it shows the trial of strength between the monolithic ERP applications and more specialist applications looking to provide the same functionality.

In this section we have introduced some of the issues of managing e-business infrastructure. These are examined in more detail later in the book. Figure 3.19 summarizes some of these management issues and is based on the layered architecture introduced at the start of this section with applications infrastructure at the top and technology infrastructure towards the bottom.

Source: Dave Chaffey (2010), E-Business and E-Commerce Management: Strategy, Implementation and Practice, Prentice Hall (4th Edition).

4 Jun 2021

4 Jun 2021

4 Jun 2021

4 Jun 2021

4 Jun 2021

3 Jun 2021